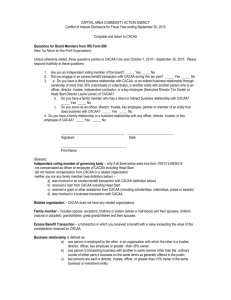

Trustees Indemnities, Equitable Liens

advertisement

Trustees Indemnities, Equitable Liens, Subrogation and Caveats By Andrew Steele May 2013 Bill Patterson’s June 2011 Trust Conference paper entitled “Trustees indemnities, equitable liens, subrogation and caveats – has the law taken a wrong turn?” 1 states that the Judgment in Official Assignee v Menzies 2 leads the law down a “blind alley”. The background in Menzies was that Mr O’Leary purchased what transpired to be a “leaky home” from Mr Bainbridge, a property developer. A claim ensued and an arbitration award was made against Mr Bainbridge which ultimately resulted in his bankruptcy. Mr O’Leary was the sole creditor in the bankruptcy. Earlier, Mr Bainbridge had made loans to the trustees of the Kahurangi Trust, of which he, Mrs Menzies and Mr Palmer were trustees. In separate proceedings, the Official Assignee pursued repayment of the loans as a “creditor” of the trustees. The Official Assignee claimed a right to subrogate into Mr Bainbridge’s “trustee” right of indemnity against the trust’s property supported by an equitable lien and, in reliance on this right, placed a caveat on the trust’s property. By this time, Mr Bainbridge was no longer a trustee. The Judgment in Menzies related to the Official Assignee’s application to sustain its caveat. Associate judge Bell held that the lien gave rise to an equitable interest which, in turn, constituted a caveatable interest and granted the application. Mr Patterson states that the decision is wrong because: • • • A trustee’s equitable lien does not confer a right to caveat trust property 3. An indemnity affects the rights and interests of the trust beneficiaries and is not a direct claim against the trust assets. This is why a subrogating creditor must get a Court order to enforce its claim 4. A creditor of a trustee has no entitlement to or claim to be beneficially interested in trust assets, so there can be no right to caveat, hence they can only enforce their right by way of an order of the Court 5. This article explores these opinions. 1 Page 245 of the June 2011 NZLS Trusts conference book High Court Auckland, CIV-2010-404-5457, 14 February 2011 3 P259 at subparagraph (a) of the Trusts conference book 4 Page 249 of the conference book 5 Page 259 subparagraph (f) of the Trusts conference book 2 2. The trustee’s right of indemnity Mr Patterson’s analysis starts with the question “What then are the relevant principles?” The answer begins with passages from Lewin on Trusts 6 including the following (underlining by Mr Patterson): A trustee’s right of indemnity affords protection to the trustee by entitling him to pay or reimburse himself out of the trust property in respect of the personal liabilities which he incurs in the administration of the trust, but normally only where the liabilities are properly incurred. Thus there are two distinct relationships. The first is the relationship between the trustee and the third parties with whom he deals in the administration of the trust. This will generate personal liabilities for the trustee, and so far as these personal liabilities are concerned, the terms of the trust will generally be of no direct importance. The second is the relationship between the trustee and the beneficiaries in connection with the liabilities incurred out of the first relationship. The second relationship is concerned with the trustee’s right of indemnity, and depends upon the terms of the trust and the manner in which the trust has been administered by the trustee. Normally, there will be no direct dealings between the third parties and the beneficiaries. The third party will claim against the trustee and the trustee will claim against the trust property in which the beneficiaries are beneficially interested …. In respect to this passage, Mr Patterson comments: The underlined statement is important. The claim to indemnity affects the rights and interests of the trust beneficiaries. It is not a direct claim against trust assets. This is why, as will be 7 seen, a subrogating creditor will need to get a Court order to enforce its claim . These comments are difficult to reconcile with what Lewin on Trusts state earlier in the same paragraph that: A trustee’s right of indemnity affords protection to the trustee by entitling him to pay or reimburse himself out of the trust property in respect to liabilities which he incurs in the administration of the trust … (the writer’s underlining). And also what the authors state later in the same paragraph that: Of course a third party may have a direct proprietary remedy against the trust property, for example by virtue of an express charge. More importantly in the present context, a third party who has no more than a personal remedy against a trustee may be able to reach the trust property by way of subrogation to the trustee’s right of indemnity, or may be able to reach the trust property through a direct equitable charge. (the writer’s underlining) In the writer’s view, Lewin on Trusts does maintain that a trustee’s indemnity entitles a claim direct against the trust assets and, by subrogation, a creditor may secure that right too. Reimbursement versus exoneration Mr Patterson states that a lack of understanding of the distinction between the right of reimbursement (also known as recoupment) and the right of exoneration has caused confusion in some Australian decisions 8. 6 th 18 edn para 21.10 Page 249 of the Trusts conference book 8 The “confusion” seems to be reference to 3 Australian Supreme Court decisions; Re Byrne Australia Ltd [1981] 1 NSWLR 394, Re Enhill Pty Ltd [1983] VR 561 and Re Suco Gold Pty Ltd (In liq) (1983) 33 SASR 99. This is discussed by Mr Mike Whale in his paper on “Trust Insolvency” for the 2009 Trust Conference at page 113 of the conference book. 7 3. An explanation of the distinction between reimbursement and exoneration may be found in Scott on Trusts 9, approved by the Australian High Court in Commissioner of Stamp Duties 10 (NSW) v Buckle , as follows: Where the trustee acting within his powers makes a contract with a third person in the course of the administration of the trust, although the trustee is ordinarily personally liable to the third person on the contract, he is entitled to indemnity out of the trust estate. If he has discharged the liability out of his individual property, he is entitled to reimbursement; if he has not discharged it, he is entitled to apply the trust property in discharging it, that is, he is entitled to exoneration. The High Court of Australia in Octavo investments Pty Ltd v Knight 11 held that until a trustee reimburses or exonerates himself, his interest in the trust assets becomes a proprietary one. The Court explained 12: If the trustee has incurred liabilities in the performance of the trust then he is entitled to be indemnified against those liabilities out of trust property and for that purpose he is entitled to retain possession of the property as against the beneficiaries. The trustee’s interest in the trust property amounts to a proprietary interest, and it is sufficient to render the bald description of the property as “trust property” inadequate. In regard to the right of exoneration, because the trustee does not use his own funds but instead applies the trust’s funds to meet the Trust Creditor’s liability, the trustee receives no beneficial interest in the trust assets. Professor Ford in his article “Trading Trusts and Creditors rights” notes the difference and says that as a consequence this form of the ‘right of indemnity’ is unlikely to give rise to a proprietary interest in the trust assets. Instead, he believes that the right is better described as a power, supported by a charge or lien, to retain and keep available trust property for the purposes of effecting the indemnity 13. Despite the differences between reimbursement and exoneration, texts and judicial authorities call both rights of indemnity variously; a beneficial and a proprietary interest 14 or a first charge 15 or an equitable lien 16. Having regard to the varying descriptions, Mr Patterson states “confusion abounds” 17. If there is “confusion”, then it seems to reflect the illusive nature of the right rather than a misunderstanding of the difference between reimbursement and exoneration. For instance, the right is an equitable charge over trust assets because it is enforced by the court in its equitable jurisdiction, on the other hand it is not a security interest. It is not a right of personal indemnity as between trustee and beneficiaries; the right is against trust assets. The cases talk of a proprietary or beneficial character to the right, but it falls short of “ownership” in the full sense. The right has properties of a lien in the sense that it enables the trustee to secure possession of the trust assets as against the beneficiaries, but it survives even after loss of possession of the assets and or removal of the trustee from his trusteeship. 9 Scott on Trusts, 4th ed (1988), vol 3A, at 246 [1998] HCA 4, 192 CLR 226 at 245 [47] 11 [1979] HCA 61 12 At paragraph 23 13 MULR Vol 13, June 1981 page 25 and 26 14 Octavio investments at paragraph [29] 15 Re Exhall Coal Co Ltd 901986 35 Beav 449 at 452-453; 55 ER 970 at 971 per Lord Romilly 16 Vacuum Oil Co Pty Ltd v Wiltshire [1945] HCA 37; 72 CLR 319 at 335 17 Page 255 of the Trusts conference book 10 4. 18 The Australian High Court explained : • • • • • To the extent that the assets held by the trustee are subject to their application to reimburse or exonerate the trustee, they are not "trust assets" or "trust property" in the sense that they are held solely upon trusts imposing fiduciary duties which bind the trustee in favour of the beneficiaries. The term "trust assets" may be used to identify those held by the trustee upon the terms of the trust, but, in respect of such assets, there exist the respective proprietary rights, in order of priority, of the trustee and the beneficiaries. The right of indemnity is a first charge upon the assets amounting to a proprietary interest. A court of equity may authorise the sale of assets to satisfy the right to reimbursement or exoneration. In that sense, there is an equitable charge over the "trust assets" enforceable in the same way as any other equitable charge. The enforcement of the charge is an exercise of the prior rights conferred upon the trustee as a necessary incident of the office of trustee. It is not a security interest or right which has been created, whether consensually or by operation of law. The preponderance of texts, including Lewin on Trusts 19, and authorities seem to favour the view that the right of indemnity equates to an equitable charge conferring an equitable interest. The significance of the trustee’s insolvency Any significance between the right of reimbursement as opposed to the right of exoneration where the trustee is solvent is otiose. Insolvency changes the situation because creditors then must vie for a share of the trustee’s insufficient assets, be they personal or trust assets. An insolvent trustee may have two types of personal unsecured creditors: • • Those incurred other than in connection with the administration of any trust. For convenience, these may be called the trustee’s “Personal Creditors”. These creditors have no right of indemnity against any trust fund. Those incurred out of dealings in the administration of a trust. For convenience, these may be called the trustee’s “Trust Creditors”. While the trustee is personally liable for these creditors too, he additionally enjoys a right of indemnity against the trust property in order to discharge them. Either type of creditor may bankrupt the trustee who is personally liable to both. Upon bankruptcy, the official assignee will be vested with the trustee debtor’s property and powers, including any unsatisfied trustee indemnity. If the unsatisfied trustee indemnity is that of reimbursement (recoupment), then any recovery from trust assets to satisfy the indemnity will be available to meet the trustee’s Personal Creditors. This is because the trust funds applied in reimbursement represent the insolvent trustee’s personal property (i.e. owned legally and beneficially) 20. If on the other hand the unsatisfied trustee indemnity is that of exoneration, then the Trust Creditors does not need to place the trustee into bankruptcy. Provided the trustee is insolvent or otherwise unable to exercise the right himself, they may seek to enforce the right 18 Chief Commissioner of Stamp Duties (NSW) v Buckle (1998) 192 CLR 226 at paragraphs [47] to [50.] 19 Para 21-33 20 It is in this area that Mr Mike Whale highlighted a “confusion” or conflict between 3 Australian decisions. 5. 21 of indemnity by subrogation directly . This option is not open to the Personal Creditors for whom the right of subrogation does not arise. They must bankrupt the trustee to get at (indirectly through the Official Assignee) the “asset” comprised in the unsatisfied trustee indemnity arising from reimbursement (recoupment). In practical terms, the word “directly” as used above, in fact, means the creditor would apply to the Court for a declaration of the existence of the indemnity, the entitlement to subrogate and the existence of the equitable charge/lien along with orders seeking consequential relief directed to realisation of that interest i.e. orders for sale of the trust assets 22. 23 In the meantime and by operation of law , the Trust Creditors will already have stepped into the shoes of the insolvent trustee, and so, become the holders of the indemnity right and the equitable lien or charge that accompanies that right. The differing positions as between Personal Creditors and Trust Creditors is why Lewin on Trusts states 24: It is necessary to identify which creditors are entitled to have recourse to the interest represented by the trustee’s right of indemnity. … On principle, therefore, in the trustee’s bankruptcy or winding up, the proceeds of his right of indemnity are available to all creditors without distinction only so far as those proceeds represent reimbursement of payments out of the trustee’s own funds; if the trustee had remained solvent, he could have done as he pleased with monies reimbursed to him. But otherwise the proceeds of the right of indemnity can be applied only in paying the trust creditors, not the personal creditors. In support of his proposition that the right of reimbursement creates an equitable charge over the trust property, while a right of exoneration does not 25, Mr Patterson quotes the following passage from Lewin on Trusts 26(underlying by Mr Patterson): … While a right of reimbursement is a proprietary charge or interest freely disposable by a trustee for his own benefit or for the benefit of his own general creditors, a right of exoneration however, benefits a trustee only to the extent that it allows him to resort to the trust fund for the purpose of payment of an expense of the trustee within the scope of his right of indemnity which otherwise would be borne by the trustee personally and so does not confer any proprietary charge or interest allowing the trustee to resort to the trust property for the purpose of satisfying claims of his own creditors. In the writer’s view, Mr Patterson’s proposition goes beyond what the passage from Lewin on Trusts intended. If his proposition was correct, then Lewin would not, presumably, have commenced the paragraph he quotes with: A trustee … has a first charge or lien upon the trust fund, conferring an equitable interest in the trust fund, in respect of liabilities, costs and expenses covered by his right of indemnity. [sentence omitted by the writer] The trustee’s right of indemnity as secured by charge or lien comprises rights of reimbursement, exoneration, retention and realisation … 21 See footnote 29 below Levin v Ikiua [2010] 1 NZLR 400 at paragraph [123] 23 Napier v Hunter [1993] AC 713 (HL) at 736 24 in paragraph 22-24 25 Page 259 subpara (b) of the conference book 26 at para 21-33 22 6. In the writer’s view, the passage from Lewin on Trusts highlighted by Mr Patterson merely says that the proceeds from exercise of the trustee’s indemnity: • • Is available to the trustee’s Personal Creditors only where the indemnity arises from reimbursement (recoupment); and Is available only to the Trust Creditors where the indemnity arises from exoneration. The nature of right of indemnity as a “a first charge or lien upon the trust fund, conferring an equitable interest in the trust fund” is unchanged whether it arises from reimbursement (recoupment) or exoneration. All that differs is which of the trustee’s creditors may benefit from its exercise. It seems to the writer that having regard to the many texts and authorities to the contrary, it is a bold submission to contend that a trustee’s indemnity, in either of its forms, does not give rise to an equitable charge or lien over the trust assets. The creditor’s right of subrogation The right of a creditor to be subrogated into the trustee’s right of indemnity is of longstanding. Lewin on Trusts 27 states the principle in this way: Although unsecured creditors and other claimants do not have a direct claim against the trust property in respect to unsecured liabilities incurred by trustees in the administration of the trust, and cannot levy execution upon the trust property, they may by subrogation have a right to stand in the place of the trustee and enforce their liabilities against the trust property to the extent that the trustee would be so entitled. The trustee’s right of indemnity is an asset of the trusts, and the trustee’s creditors are entitled by subrogation to reach this asset and so enforce their claims against the trust property. It is of equally longstanding that the creditor’s right of subrogation only arises where it is not possible to enforce the liability against the trustee personally, for instance where the trustee has absconded, or has died or become insolvent. Lewin on Trusts 28 refers to this 29 consistently upheld principle of law . Official Assignee v Menzies – is an equitable lien a caveatable interest? Menzies is not a “creditor subrogation” case. The Official Assignee was vested with all Mr Bainbridge’s property and powers (as widely defined in sections 2 and 42 of the Insolvency Act 1967) upon bankruptcy. It follows that the pre-condition that the trustee be unable to enforce their right of indemnity did not arise. His Honour states that the Official Assignee relied on 3 cases to support the submission that an equitable lien is a caveatable interest 30, namely: • • 27 31 Zen Ridgway Pty Ltd v Adams . Custom Credit Corporation v Ravi Nominees Pty Ltd 32. Paragraph 21.38 at paragraph 21-41 29 See: Ex Parte Garland [1804] Eng R 336; (1804) 10 Ves 110, Owen v Delamere [1872] LR 15 Eq 134. His Honour Babington LJ famously stated in Re Geary (alt cit Sandford v Geary) [1938] NILR 153 (CA) at 162 “Assuming that the creditor has this right must he sue the executor in the first instance before taking proceedings for administration even though he will obtain a judgment which Bacon VC described as a “fruitless” judgment in Owen v Delamare? I think not”. 30 Judgment paragraph [26] 31 [2009] QSC 117 28 7. • Re Nymboida River Pty Ltd (In Liq) Caveats 33 The Court in Zen Ridgway recognised that “in principle” the trustee’s lien is a caveatable interest 34, but pointed out the right of access to the trust assets by way of subrogation is inchoate unless the trustee is insolvent or it is otherwise reasonable to assume that obtaining judgment against the trustee would be pointless 35. Because the Court was not satisfied on the evidence that the right had yet formed or crystallised, it could not constitute a caveatable interest. In Custom Credit Corporation the respondent trustee owned land for the Ravi Family Trust. The appellant (Custom Credit) advanced money to a company related to the trustee. The trustee guaranteed repayment in its trustee capacity. Under the terms of the advance, the trustee “charged” its interests in any property it may have by way of security for repayment. In fact, the trustee was a ‘bare trustee’ in the sense that it owned no property legally and beneficially. Nevertheless and in reliance on this charge, Custom Credit placed a caveat on the trustee’s land. At first blush, one might be forgiven for asking, what property can be charged – the trustee only owns land as a bare trustee? The Court held that the trustee’s obligation under the guarantee created a contingent liability the entering of which gave rise, contemporaneously, to a corresponding right of indemnity. The right of indemnity was proprietary in nature and had attached a charge or lien over trust assets36. The indemnity represented a species of property that was chargeable by the trustee in favour of Custom Credit, albeit only because the charge related to the trustee’s (i.e. the trust’s) liability (thereby preserving the reimbursement - exoneration distinction) 37. 38 Interestingly, the trustee was not insolvent when it charged its right of indemnity . Mr Patterson states that Ford and Lee incorrectly cites Custom Credit Corporation as authority for the proposition that the trustee’s proprietary interest in property constitutes a caveatable interest 39. The writer disagrees. Custom Credit Corporation lodged its caveat on the trustee’s trust land in reliance on the charge given by the trustee over the trustee’s right of indemnity 40. If in law the trustee’s indemnity did not amount to an equitable proprietary interest over the trust’s assets, then Custom Credit Corporation would not have acquired a caveatable interest over them. As noted above however the term “proprietary interest” is not used in the sense of an “ownership interest” or “beneficial interest” in the trust assets, but rather as a proprietary beneficial interest in the nature of an equitable charge over the trust assets to the extent of the right to be indemnified out of those assets against personal liabilities incurred in the performance of the trust. His Honour in Custom Credit Corporation noted the trustee’s concession (before the trial Judge below) that the right of indemnity is a caveatable interest in the hands of the trustee and stated “In my opinion the concession was properly made” 41. Mr Patterson implies that the concession is an inadequate basis to support the proposition of law. In the writer’s view, 32 (1992) 8 WAR 42 at 53 Unreported Queensland Supreme Court, Ambrose J, 30 September 1988 34 Judgment paragraph [10] 35 Judgment para [13] 36 This represented a chose in action see Judgment page [56] line 15 37 page 53 line 30 38 Judgment page [55] line 29 39 Trust conference book page 247 40 rd Ford & Lee Principles of the Law of Trusts (3 edn, 1996) at para 14.270 41 Judgment at page [53] line 40 33 8. given His Honour’s careful analysis of the general principles of trustee indemnity and the nature of the right itself, it would have been extraordinary for him to endorse the concession if he believed the law did not support it. Mr Patterson does not analyse the Queensland Supreme Court’s decision in Re Nymboida River Pty Ltd (In Liq) although the Associate Judge apparently accepted it as authority in his Judgment. The facts in Re Nymboida were that prior to its liquidation Nymboida was sole corporate trustee of the Balasun Unit Trust. In that role, it incurred share trading losses. Shortly before its liquidation, the company’s directors “purported” to replace Nymboida as trustee with a new corporate trustee and attempted to transfer the company’s trust land to the new trustee. The liquidator lodged caveats claiming, among other things, a caveatable interest arising from the trustee’s (Nymboida’s) right of indemnity in relation to the trading losses and associated equitable lien against the properties the subject of the intended transfer. His Honour referred to the Australian High Court’s decision in Octavio Investments and held that the right of indemnity gave rise to a lien or charge which constituted a “sufficient interest in the land” to support the caveats. The Court responded to the applicant’s argument that the caveatable interest was inadequately described in the registered caveats by granting leave to the liquidator to amend the stated interest to read:“ … an equitable interest by way of security for an indemnity against its liability as trading trustee”. In the writer’s view, the existence of these 3 cases provide ample support for the view that an equitable lien constitutes an caveatable interest, at least in Australia. Is an equitable charge or lien a caveatable interest in New Zealand? Section 137(1) of the Land Transfer Act 1952 entitled “Caveat against dealings with land under Act” states: Any person may lodge with the Registrar a caveat in the prescribed form against dealings in any land or estate or interest under this Act if the person— (a) claims to be entitled to, or to be beneficially interested in, the land or estate or interest by virtue of any unregistered agreement or other instrument or transmission, or of any trust expressed or implied, or otherwise; or Traditionally, a caveatable interest had to be capable either immediately or in due course of being converted into an estate or interest that can be registered. Recent cases indicate a move away from the strictness of this requirement. The change is enabled by a broader interpretation of the words “or otherwise” at the conclusion of section 137(1)(a), so allowing a wider range of the kinds of interests that may support a caveat. In Superannuation Investments Ltd v Camelot Licensed Steak House (Manners Street) Ltd 42 it was held that the interest does not need to be capable of ultimate registration. This approach was followed in New South Wales in Composite Buyers Ltd v Soong 43, where the Court stated: … any equitable interest in land is sufficient to support a caveat, even if the caveator does not have a registerable instrument, and even if the caveator may not be entitled to an instrument which will lead to a recording in the register. 42 43 8/12/87, McGechan J, HC Wellington M695/87, (1995) 38 NSWLR 286 9. In my opinion, what is necessary is that there be an interest in respect of which equity will give specific relief against the land itself, whether this relief be by way of requiring the provision of a registerable instrument, or in some other way giving satisfaction of the interest claimed by the caveator out of the land itself, for example by ordering the sale of the land and payment out of the proceeds of an amount in respect of which the caveator has a charge. In Composite Buyers, the relevant caveat provisions in the Real Property Act 1900 (NSW) state: Section 74F Lodgment of caveats against dealings, possessory applications, plans and applications for cancellation of easements or extinguishment of restrictive covenants (1) Any person who, by virtue of any unregistered dealing or by devolution of law or otherwise, claims to be entitled to a legal or equitable estate or interest in land under the provisions of this Act may lodge with the Registrar-General a caveat prohibiting the recording of any dealing affecting the estate or interest to which the person claims to be entitled... In an article entitled “Can an unregisterable interest support a caveat” 44, Mr Donald McMorland suggests that the Composite Buyers approach is “clearly correct”. This broad approach was followed in Wellesley Club Inc v Wellesley Property Holdings Ltd 45, where the Judge noted both the traditional narrow view and the broad view expressed in Composite Buyers and held that: It follows, therefore, in my view, that for the purposes of determining whether there is a reasonably arguable case to the caveatable interest claimed, an equitable interest in land which gives relief against the land itself will support the caveat. In Wellesley Club Inc, the caveator’s principal argument for a caveatable interest in the property was based on the doctrine of equitable estoppel. The registered proprietor contended that, at best, the interest amounted to a mere licence and did not amount to a lease or any other interest in land. However, the Judge took the view that, in the circumstances, equity could grant relief against the property itself, and that: What may well at first glance appear only to be a licence … might well transpire ultimately to be a lease to the Club in respect of the Member’s Lounge at the very least, or alternatively, a land covenant or the like preserving the Club’s rights. In regard to this “relief oriented” approach, the Court noted that the position had been softened by the approach of the Court of Appeal in Zhong v Wang 46 quoting para 58 of that judgment where the Court said: The underlying purpose of the caveat regime could be undermined if too strict an approach were taken to the detail required to describe the interest claimed and its derivation from the registered proprietor. Authority exists to support the broad view in Waitakiri Links Limited v Windsor Golf Club Inc 47 and Hinde McMorland & Sim “Land Law in New Zealand” where the authors state 48: It is submitted that the broad view is to be preferred. 44 (1996) 7 BCB 185 (2007) 8 NZCPR 421 per Associate Judge Gendall 46 (2006) 5 NZ ConvC 194,308; (2006) 7 NZCPR 488 47 (CA132/95, 9 November 1998) 48 paragraph 10.006 45 10. 49 The authors further note : … equitable interests arise out of certain contracts. There are, however, many other ways in which equitable interests in land may come into being, for example, under trusts (whether express, resulting or constructive) and under other heads of the equitable jurisdiction, such as those relating to covenants, estoppel, and the mortgagor’s equity of redemption. ‘Equity calls into existence and protects equitable rights and interests in property…where their recognition has been found to be required in order to give effect to its doctrines’ and it has been remarked that ‘equitable interests may therefore arise impliedly in response to the dictates of equitable doctrine… In their most recent publication, Hinde McMorland & Sim continue to maintain that both an equitable charge and an equitable lien create interests in land that are sufficient to support a caveat notwithstanding that in either case the interests do not give rise to registerable instruments under the Land Transfer Act 50. If enacted, the Land Transfer Bill at Subpart 7 section 123 entitled “Caveats against dealings with land” will stop the debate since it states: (1) A person may lodge a caveat against dealings with an estate or interest in land (caveat against dealings) on the basis that the person— (a) claims an estate or interest in the land, whether capable of registration or not; In Menzies, Associate Judge Bell, held that an unregisterable equitable lien fell within the words “or otherwise” of section 137(1)(a) of the Act so as to support a caveat 51. In the writer’s view, that determination is amply justified by the authorities and texts which describe the unregisterable right of indemnity as an equitable charge and proprietary interest in the trust property, notwithstanding the absence of a definitive determination from the Court of Appeal or Supreme Court as between the traditional and broad views regarding caveatable interests. This does not necessarily mean the correct legal result occurred in Menzies as is discussed below. What were the Official Assignee’s rights in OA v Menzies? In Menzies Mr Bainbridge had loaned funds (funds that he owned legally and beneficially) to himself and his co-trustees of the Kahurangi Trust 52. He was therefore both a Trust Creditor and a trustee debtor for the same indebtedness. So: • • As a debtor under the loan agreement he was personally liable. And because the debt was incurred in the administration of the trust, he was entitled as trustee to a right of indemnity (to be exonerated) against or out of the trust’s assets; and As a creditor of the trustees for the trust, he was entitled to repayment of the loan from himself and co-trustees as personal debtors, but in the event of his and their insolvency he was entitled to subrogate into their trustee right of indemnity against the trust’s assets. The writer’s reservation about the result in Menzies arises from 2 apparently unresolved issues in the evidence. The first relates to whether Mr Bainbridge’s co-trustees were insolvent. If there was no evidence in this regard, then (as in Zen Ridgway) the right of 49 paragraph 4.020 , Reprinted 2012 edition, Vol 1, para 10.009 (o) and (p) at page 23,155. 51 Judgment paragraph [28] 52 Judgment paragraph [15] 50 11. indemnity is inchoate or unformed, so has not yet arisen. If this is so, then no equitable interest was formed, and so, no caveatable interest can arise. The second issue relates to whether or not Mr O’Leary is a Trust Creditor. Mr O’Leary was the only creditor in Mr Bainbridge’s bankruptcy 53 and his debt arose from an arbitration award. It is unclear from the Judgment, but in the writer’s view it is critical to determine whether Mr Bainbridge’s liability to Mr O’Leary was incurred in the administration of the Kahurangi Trust. If it was, then Mr O’Leary may be a Trust Creditor 54, if not, then he is merely one of Mr Bainbridge’s personal creditors. As discussed earlier, any recovery by an Official Assignee in bankruptcy in exercise of a trustee’s right of indemnity for exoneration must be applied to discharge Trust Creditors only. If Mr O’Leary is not a Trust Creditor, then any proceeds obtained by the Official Assignee’s exercise of the indemnity cannot benefit him. It would follow in such circumstances that the Official Assignee has no right to exercise the right of indemnity and take trust funds into the bankruptcy estate. Conclusion on the caveat issue Where the writer’s views oppose those of Mr Patterson may be summarised as follows: • • • • A trustee’s right of indemnity gives rise to equitable lien or charge which does confer a right to caveat trust property. A trustee’s right of indemnity is a direct claim against the trust assets. While Trust Creditors of a trustee may not levy execution direct upon trust property, they may (for instance where the trustee is insolvent) subrogate into the trustee’s right of indemnity and thereby into the accompanying charge or lien and right to caveat. Official Assignee v Menzies was rightly decided subject to the 2 evidential matters raised above. Andrew Steele Partner – Martelli McKegg DDI: Email: Mobile: 53 +64 9 300 7625 ajs@martellimckegg.co.nz +64 21 673 252 Paragraph [6] The word “may” is used because the extent of a trustee’s right to be indemnified for tortious wrongs is an issue that is capable of differing views. 54