Resourcing and Talent Planning

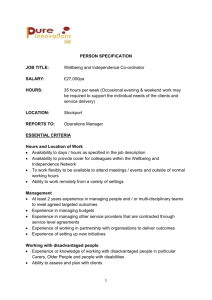

advertisement