A Theology for Resettlement - Otago University Research Archive

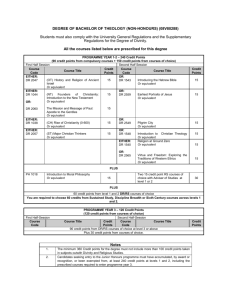

advertisement