Annex 4 - Mikhail Khodorkovsky

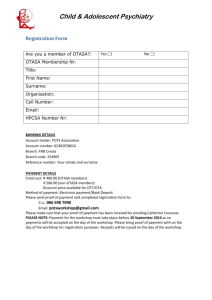

advertisement