EXCEL SPREADSHEET TUTORIAL Note to all 200 level physics

advertisement

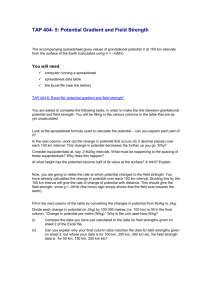

EXCEL SPREADSHEET TUTORIAL Note to all 200 level physics students: You will be expected to properly format data tables and graphs in all lab reports, as described in this tutorial. Therefore, you are responsible for knowing the material contained here; even if the tutorial is not given as a regular assignment. Included at the end of this tutorial is a short section on importing graphs from EXCEL into an MS Word document. This information will also be useful for writing lab reports. Everything in this tutorial, including all exercises, has been done by the author on a PC running Windows XP. This tutorial has been updated from a previous version and is based on the newest versions of EXCEL and MS Word; Excel 2002 and Word 2002. The Windows NT Workstations in the DH Hill Library Unity lab, and in the Unity Lab at the laundry building on Stinson are running these versions. Other labs on campus with Windows stations should also have the latest versions available. If not, please inform Dr. Chilton in the physics department (jhchilto@unity.ncsu.edu). This tutorial goes with a 2nd tutorial on using EXCEL to do curve fitting for data analysis. At this time, only PY205 and PY208 students will be expected to know how to do the curve fits in EXCEL. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Purpose 2. Getting Started 3. An Illustrative Exercise, Part 1: - Entering Text, Formulas and Data A. B. C. D. A Clean Sheet Correcting Mistakes Entering Numbers Entering Formulas 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Inserting a New Row Entering the Formula Fill-Down Procedure More on Formulas and Cell References Setting the Number of Displayed Significant Figures 4. An Illustrative Exercise, Part 2: - Graphing Data A. B. C. D. Making Graphs Titling the Graph Editing the Legend Moving the Graph 5. Importing an EXCEL Spreadsheet Graph into a MS Word Document APPENDIX: TERMINOLOGY 1. PURPOSE. The purpose of this tutorial is to acquaint you with a few commonly used features of the spreadsheet program Microsoft EXCEL. Spreadsheet programs (often called simply "spreadsheets") are powerful applications which enable you to make extensive calculations without knowing a programming language. EXCEL will be used in this lab course to tabulate data, graph data and formulas, and to assist in data analysis. Also included in this tutorial are instructions to properly format your graphs and label the axes and title of a graph. You will be expected to follow these instructions by properly formatting and labeling all graphs created in any physics lab assignment. 2. GETTING STARTED. To start Microsoft EXCEL double-click its icon. The computer will open the EXCEL application. When opened, the screen should appear as shown below. The data field consists of rows, labeled with numbers, and columns, labeled with letters. Across the top is the menu bar. [The menu bar and tool bars may contain different items depending on which version of EXCEL you are running and how it is customized.] Figure 1 - Appearance of EXCEL window when program is started. The junction of a row and a column is called a cell. An active cell is distinguished from other cells by a darker border. The active cell in the Figure is A1, as shown by both the dark border and the address in the Reference area. Other important elements of the Excel screen are indicated in the Figure. Click the mouse on any cell. Notice how the arrow keys move the active cell. The mouse can move the visible part of the workspace in the spreadsheet. To move the workspace left or right, position the mouse on the scroll box located in the horizontal scroll bar at the bottom edge. Press the mouse button, move the scroll box either to the left or to the right, and then release the mouse button. To move the workspace up or down, position the mouse on the scroll box located in the horizontal scroll bar at the right edge of the spreadsheet, press the mouse button, move the scroll bar either up or down, and then release the mouse button. If you wish to quit the program at any time, choose Exit from the File menu. If you have not saved the spreadsheet, the program will give you the opportunity to do so before quitting. 3. AN ILLUSTRATIVE EXERCISE, PART 1 - Entering Text, Formulas and Data. In this section and the next, you will begin solving a physics problem using EXCEL. Problem: An object is released from rest and falls freely. Compute the position and velocity at each of the following times: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 s. Take the origin O at the elevation of the starting point, the y-axis vertical, and the upward direction positive. After you have computed the position and velocity for each instant of time, make a plot of position and velocity versus time. Solution: In this section you will create a spreadsheet that contains values for time and calculates the position and velocity of the falling object. A. A Clean Sheet: Begin with a blank spreadsheet by selecting New from the File menu (or by the keystroke Ctrl+N). You will now type text into cell A1 that states the purpose of the spreadsheet. Select cell A1 Type Problem: Calculation of position and velocity of a falling object press Enter Notice that when you type information in a cell, the information will appear in both the cell and the formula bar (see Figure above for the location of the formula bar if you are unsure). [If this long title wraps within the cell, change the alignment as follows: Within the Format menu, select Cells..., then click on the Alignment folder tab. You will see three check boxes under the heading Text control. Click on each box to remove any check marks present.] B. Correcting Mistakes: If you make a mistake Click the cell containing the error Click the mouse in the formula bar and correct the mistake by deleting and adding text as needed. Press Enter C. Entering Numbers: Before you enter a column of numbers, it is a good idea to label the column. The label for column A will be Time (s). To enter this label Select cell A2 Type Time (s) press Enter [If this title doesn't fit inside its cell, you can widen the cell as follows: Set the cursor over the boundary between the column headings A and B. Drag the boundary to the right (or to the left to narrow the column).] The values for the time will range from 0 to 10 in regular steps. To enter the sequence of numbers from 0 to 10 in column A Select cell A3 Type 0 Press Enter (The computer will automatically move the active cell from A3 to A4 when you press Enter.) Type 1 in cell A4 and press Enter Select cells A3 and A4. You will see a tiny box in the lower right-hand corner of cell A4. Drag that little box downward to cell A13. The computer will perform an autofill. It's a good idea at this point to save your file by selecting Save As from the File menu and following the instructions in the dialog box. You should get in the habit of saving files every few minutes to prevent the loss of work due to a power failure or a computer crash. Be sure to give it a unique file name that you can remember. Usually, at first Windows will give it a default name like “Document1”, or “Worksheet1”. Be sure to take your time and type in a new file name that is unique to you, especially if you are using a computer that other people use, such as in the labs or Physics Tutorial Center. It is highly recommended that you save it to your own floppy disk if possible. D. Entering Formulas: In this section you will learn how to type in formulas that will calculate the position and velocity of the falling object. You will need two equations: one for the position and another for the velocity. The equations are: 1 and v y = v 0y + a y t . y = y 0 + v 0y t + a y t 2 2 There are three constants in these two equations that do not change as the body falls. initial position initial velocity acceleration yo = 0 voy = 0 ay = -9.8 m/s2 You should now set up a section on the spreadsheet to write these constants. Cells A3 - A5 would be convenient, but you have already put information into them. You can add cells to get around this problem. 1) Inserting a new row: To add a row of cells between rows 1 and 2, Click the shaded row-number button 2 on the left edge of the window. The whole row will become dark signifying it has been selected. Choose Rows from the Insert menu. The information in cells A2 - A13 has been moved down one cell. Add four more rows between rows 1 and 2. If you have done this correctly, you should have 5 empty rows between rows 1 and 7. If, in the future, you need to delete a row, then Click on the row number of the row to be deleted. Choose Delete from the Edit menu. Now you have room for the constants. Select A3 Type Initial Velocity (m/s) and press Enter Select C3 Type 0 and press Enter Select A4 Type Initial Position (m) and press Enter Select C4 Type 0 and press Enter Select A5 Type Acceleration (m/s/s) and press Enter Select C5 Type -9.8 and press Enter 2) Entering the formula: The formula to be evaluated for position will go into column B. You need to give column B a title, call it Position (m). This is the correct format for labeling a column in a data table. The label includes the name of the physical quantity with the units in parentheses. Data tables in a spreadsheet should be labeled properly, just like the ones in a lab report. Select B7 Type Position (m) and press Enter Now you are ready to enter the formula for the position of the falling object. 1 To enter this formula, y = y 0 + v 0y t + a y t 2 2 Select B8 Type = $C$4+$C$3*A8+(1/2)*$C$5*A8^2 (Note: We will explain the use of the $ and other symbols below.) Press Enter You start with the equal sign (=) to tell Excel that what you type next is a formula. You can use either upper or lower case letters for the column label. The formula will be visible in the cell as well as in the formula bar. Note: Excel interprets / as "divide by" and * as "multiply by". The caret (^) raises a quantity to a power. For example, A8^2 squares the value contained in cell A8 3) Fill down procedure: Rather than typing this equation into the rest of the cells B9 through B18, you can select the contents of cell B8 and copy them down into the rest of the cells. Select cell B8 Note the tiny box at the lower right-hand corner of the cell drag that little box down to cell B18 4) More on formulas and cell references: The computer automatically copies the formula into cells B9 through B18, changing the references to variables as necessary (click on those cells in sequence and see how the references to values of time (originally A8) are changed, but the references to the constants e.g., $C$4 are not changed). The formula you typed into cell B8 contains some new symbols. The dollar sign symbol ($) is used when you do not want the reference of a cell in a formula to change when copying and pasting from one row or column. In the formula that you entered, $C$3 is an absolute reference to the cell that contains the value for the initial velocity. You do not want this value to change from one row to the next so you type the location of the cell using dollar signs preceding the column letter and row number. When you want the reference to a cell to change from one row to another, you use a relative cell reference; leave out the dollar signs ($) and just type the letter and numeral specifying the cell location. For example, the value in cell A8 (the time) is a relative reference that you want to change from one row to the next. Use absolute reference for constants and relative reference for variables. Remember to save your spreadsheet (Ctrl+S) often. Now you will enter the formula for the velocity. First give column C the title Velocity (m/s). Select C7 Type Velocity (m/s) and press Enter The formula for the velocity is v y = v 0y + a y t . To enter this formula, Select C8 Type =$C$3+$C$5*A8 and press Enter Copy this formula into cells C9 - C18 using the fill down procedure 5) Setting the number of displayed significant figures: The values for the position and the velocity may be displayed with too many (i.e., non-physical) significant digits. To change the format of all the numbers to display only two decimal places, Highlight B8 through C18 by clicking on cell B8 and dragging to cell C18 Choose Cells... from the Format menu The Format Cells Dialog Box will come up Choose the Number folder Select Number on the left, and type the numeral 2 into the Decimal places textbox Click OK (or press Enter) The numbers displayed in the spreadsheet now have the form 0.00. You have not truncated the value in the cell or in the computer's memory. Excel merely rounds the stored value to the number of digits you specify for display purposes only. In other words, when Excel uses this number in a calculation it uses the value before rounding, not the value you see on the screen. Your spreadsheet should appear as in the figure below. (In this picture, I have chosen to save this spreadsheet with the File Name "Falling Body", which appears at the top of the spreadsheet.) Make sure your spreadsheet looks like this before you proceed. If not, you should repeat the exercise correctly until it does (feel free to give yours a different file name than "Falling Body" if you like). Figure 2 - What your spreadsheet should look like at this point. 4. AN ILLUSTRATIVE EXERCISE, PART 2: - Graphing Data. A. Making Graphs: This section will guide you through the graphing process. Select cells A8 - C18 Locate the Chart Wizard macro button in the tool bar Click on the Chart Wizard macro button Double-click on the XY (Scatter) chart type Push the Finish button (or press Enter) You should now see a graph (called a "chart") of your position and velocity data versus time. You can move your graph by dragging one of its four sides, and you can re-size it by dragging a corner. There are several things you should notice about this graph: 1) First: In science, engineering, or mathematics when we say plot "A versus B" we mean that A goes on the y-axis (vertical) and B goes on the x-axis (horizontal). In other words, "A versus B" means that B is being treated as the independent variable and A as the dependent variable. In mathematics we would say “y is a function of x” and plot y versus x (we would NOT say “x versus y” unless we wanted x on the vertical axis). This may sound trivial, but students often get this backwards. In order to analyze data properly, if an experimental procedure instructs you to plot “Quantity #1 versus Quantity #2” then Quantity #1 goes on the y-axis. You should learn this terminology now since it is standard terminology in all science, engineering, and mathematics work. 2) Second: When you select several columns of data for graphing, EXCEL always assumes that the first column farthest to the left is the independent variable; in other words the x-axis. In our case this was the Time(s) values in the first column (column A, cells A8 through A18). These will be the values assigned to the horizontal axis in the graph. When you create data tables for graphing, you will save yourself a lot of trouble and confusion if you get in the habit of putting the “x-axis” values in the first column on the spreadsheet. It does not have to be column “A”; it just has to be the column farthest to the left out of all the columns with data you are going to select when you make the graph. 3) Third: By selecting three columns of data as in this example, EXCEL assumed that the second and third columns (B and C) were two distinct sets of y values, and it plotted each one separately versus the same x values from column A. Both Position(m) (column B) and Velocity(m/s) (column C) were dependent variables. This simply allowed us to plot two functions on the same graph. Most of the time you will only plot one function per graph, but this shows us how to do multiple plots on one graph if desired. You would not normally put two functions on the same graph, unless there was a need to compare two things (in this case we can compare Velocity and Position for the falling body). B. Titling the Graph: Next, we will learn the proper way to assign titles and labels to the axes and graphs. Any graph needs to be labeled properly, especially when multiple plots appear on the same graph. All graphs should have the two axes labeled as well as a title. To attach a title to the graph, Click on the chart if it is not already selected Choose Chart Options... from the Chart menu Click on the Titles tab Fill in the Chart Title textbox with an appropriate title (see note below for what is an appropriate title for the graph) titling the x-axis: To attach a title to the x-axis, Select the Value (X) Axis text box and type Time (sec) titling the y-axis: To attach a title to the y-axis, Select the Value(Y) Axis text box and type Position (m) and Velocity (m/s) When you are satisfied with your titles, click OK or press Enter An appropriate title for this graph would be "Position and Velocity vs. Time". In engineering and science the title of the graph simply states what is plotted versus what, using the convention we stated before (y versus x). For example, a plot of acceleration versus time would simply have the title "Acceleration vs. Time", a plot of force versus mass would simply have the title "Force vs. Mass", etc. As much as you may want to be creative with your title, you should avoid any other form. For example "Falling Bodies" would NOT be an appropriate title, even if it was the title of an experiment and this was a plot of your data. This does not include the statement of what is plotted versus what, and it is too vague in general. It is okay to add a short descriptive phrase to the title, but it is not necessary. For example "Position and Velocity vs. Time of a Falling Body" is okay, because it still contains the "y vs. x" information. Standard rules for capitalization in a title are followed, and you may always abbreviate "versus" using the lower case "vs.". The proper way to label each axis is with the name of the physical quantity represented on the axis and its units in parentheses. In our case the x-axis represents time in units of seconds, so it is labeled Time (sec). Our y-axis was both position in meters and velocity in meters per second, and it is labeled Position (m) and Velocity (m/s). Note that the units are lower case and abbreviated. Both (s) and (sec) are acceptable for "seconds". Again, these are standard conventions for scientific and engineering graphs, and you should learn to follow them. C. Editing the Legend: The 2 separate graphs are distinguished by 2 sets of symbols for their respective data points on the graph. The legend labels the 2 sets of point symbols. When there is only one plot on a graph, you should remove the legend. Notice the small box next to your graph that says "Series 1" and "Series 2" with the shape and color of the two respective data symbols next to those labels. This is the Legend. You should remove the legend in cases where there is only 1 set of y values. If you need to remove the legend Right-click on it and hold the mouse while selecting "Clear" from the choices shown. To change those labels in the legend click on the graph, select Source Data ... from the Chart menu, then click on the Series folder tab Select Series 1, and type Position (m) in the Name textbox Select Series 2, and type Velocity (m/s) into the Name textbox When you are satisfied with your titles, click OK or press Enter Drag the legend box to a spot inside the graph where it won't obscure the curves or labels. At first it is outside the actual graph area. A clear spot on the graph is good because it allows you to make the graph area as large as possible, since there will be left over space after you move the legend. Note that if you click on the actual graph inside the chart window, it has its own handles for resizing it inside the larger chart area. Click on the handle at the lower right corner and drag the chart to make it fill as much of the larger chart window as possible. D. Moving the graph: You can move the chart to any location you want on the spreadsheet. For this example, you can move the corner of the chart to cell D2. Try this now. Click anywhere on the spreadsheet outside the chart Click the chart border and drag the chart near cell D2 Align the upper left hand corner of the chart near the upper left hand corner of the cell Release the mouse button Your spreadsheet should look similar to the one shown in the figure below. If it does not, you should repeat this exercise until you can do it properly. Figure 3 - Completed spreadsheet and graph. 5. IMPORTING AN EXCEL SPREADSHEET GRAPH INTO A MS WORD DOCUMENT You can easily import a graph from EXCEL into an MS Word document as an image. You should try to do this when writing your lab reports in order to make them look neat and professional. You should be able to use a similar technique with other word processors and spreadsheet programs, but they are not discussed here. Here are the steps: Open your spreadsheet in EXCEL that contains the graph; at the same time open the document in MS Word that you plan to put the graph in. In EXCEL, click on the graph to make it active. From the Edit menu in EXCEL choose Copy. At this point a moving dashed line should appear around the border of your graph. This signifies that the graph has been copied to the "clipboard" and Windows is waiting for further action. Click your mouse in the Word document at the location you want to place the picture, making the cursor blink there. Click on the Edit menu in Word and choose Paste Special. DO NOT choose normal "paste". You will see a window where you can highlight what format you want to paste the graph as. Choose "Picture (Enhanced Metafile)". Click Okay. Once you have done this, the graph will appear in the document as an image. You can move it, center it, resize it, etc. now in MS Word. Below is my graph that I just pasted into this document (I removed the gray background on the graph area in EXCEL first). I have centered it and made it smaller (it was very large at first and it was left justified on the page). Position and Velocity v s. Time for a Falling Body 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 Position (m) and Velocity (m/s) 0 -100 -200 -300 -400 Position Velocity -500 -600 T ime (s) Figure 4 - My graph of "Position and Velocity vs. Time", imported from EXCEL. APPENDIX: TERMINOLOGY Keyboard entries are specified in bold face A. KEYBOARD TERMINOLOGY 1. Press Press means to push down on a key. For example, press return. By this action the user tells the computer to accept commands and other input. 2. Type Type means to press a series of keys in succession. For example, when PI() is typed into a formula, EXCEL interprets it as the number 3.1415927···. 3. Keystrokes Keystrokes are short-cut alternatives to using the mouse to pull down menu commands. A keystroke is often a combination of two keys pressed simultaneously. For example, pressing the control key and S (not shift-S) simultaneously causes the active document to be saved. This operation is designated by Ctrl-S. The control key is the one near to the space bar labeled with Ctrl. B. MOUSE TERMINOLOGY Moving the mouse with your hand moves a pointer around the screen. The shape of the pointer indicates its function at the current time and location. In Excel, the pointer typically changes from an arrow to + or an I-bar. 1. Click means to position the pointer on top of a symbol on the screen and then quickly press and release the button on the mouse. 2. Right-click means to click (and usually hold down) the mouse button that is on the right hand side of the mouse. 3. Double-click means to click twice rapidly. 4. Drag means to position the pointer on top of a symbol on the screen, press and hold down the mouse button, move the pointer to somewhere else on the screen, and then release the mouse button. Dragging an icon moves it to a different place on the screen. 5. Select means to click an on-screen symbol (called an icon ), data cell, section of text, etc. Usually, the icon of a selected object (for example, a file) will appear white-on-black instead of black-on-white. You first select an object, then choose a command to affect it. A group of cells is selected by holding down the mouse button and dragging the pointer across them. 6. Choose A from the B menu means to position the pointer on top of the word or symbol "B" located on the menu bar across the top of the screen, drag down to open the associated menu, position the highlighting bar over the menu item "A," then release the mouse button. If you change your mind and do not want to choose any menu item, move the pointer off the menu before releasing the mouse button. If a menu item appears in dimmed letters, that item is not currently available. If a check symbol appears beside a menu item, it is a turned-on option. If the names of keys appear beside a menu item, you can choose that item directly from the keyboard by pressing those keys simultaneously (see Key Strokes in the previous section). In addition to menus, some programs feature on-screen buttons. You use the mouse to click a button to choose the corresponding option or command. A button is not a key on the keyboard! C. WINDOW TERMINOLOGY A window is an enclosed area of the screen. Several windows can appear on the screen at once and they can overlap, but only one window can be active at a time. Special windows called dialog boxes may pop-up on the screen to provide warnings, ask you for information, offer choices, etc. The area on the screen that is not inside any window is called the desktop. If you click the mouse in the desktop area, none of open windows will be active. To make a window active, click on its title bar at the top of the window. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Evolution of this Document: Adapted by Paula Vetter Engelhardt 9/93 from the Excel Spreadsheet Tutorial published by the Physics Courseware Evaluation Project at North Carolina State University. Revised 12/97, 8/98 and 8/01 by Richard Mowat. Revised 8/02 by Ted Horton and Martin Dewitt. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------