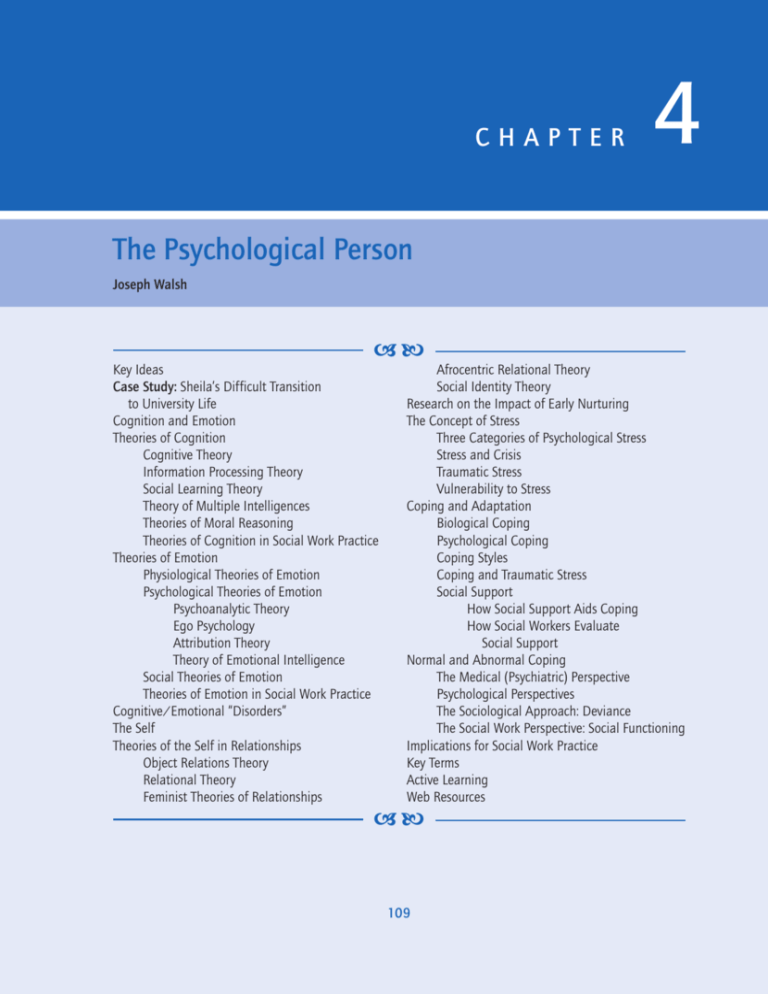

The Psychological Person

advertisement