A literature review of the value of vocational qualifications

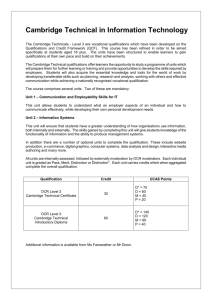

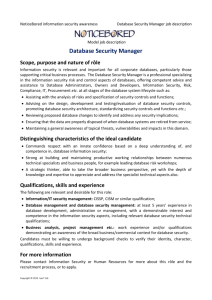

advertisement