An Unholy Trinity: The Three Ways Employees Embezzle Cash

advertisement

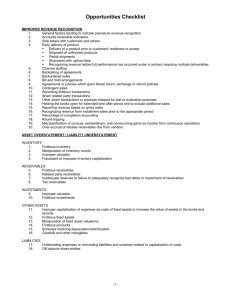

An Unholy Trinity: The Three Ways Employees Embezzle Cash. BY JOSEPH T. WELLS n the U.S. alone, occupational fraud and abuse may carry a price tag of more than $400 billion. Such crimes include embezzlements of cash that aren't necessarily complicated - just covert, insidious, and potentially devastating. On his third day as chief internal auditor for Reader's Digest, Terence McGrane stepped into a homer's nest. It all happened innocently enough. While learning the ropes on his new job, McGrane met with one of the vice presidents to learn more about the company's accounts payable system. McGrane brought a stack of sample invoices to the meeting. The vice president, routinely reviewing the documents, stopped suddenly. The invoice in front of him bore his name. "That is not my signature, " the vice president said. He and McGrane quickly found four other invoices supposedly authorized by the vice president. All were forgeries. The vice president was baffled, but McGrane recognized the signs of a fraudulent billing scheme. McGrane soon confirmed his suspicions. The financial jolt registered $1,057,000 in losses attributable to one Albert Miano. A supervisor in the painting department, Miano had worked for the company for more than 10 years. He was married and outwardly very stable; but the facts were irrefutable. Miano had created phony invoices for painting contractors who didn't exist, forged the approval of a vice president, and deposited the proceeds into his own bank account. Only about $400,000 was traced to tangible purchases, which included boats, automobiles, and homes; he was earning about $30,000 a year. Mysteriously, the other $700, 000 in cash was never located. Miano served two years in prison. THE COST OF CRIME According to the 1996 Report to the Nation on Occupational Fraud and Abuse, a study conducted by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, embezzlement schemes such as Miano's are both prevalent and incredibly costly. Also known as The Wells Report, the study concludes that the average company loses about six percent of its gross revenues to all forms of occupational fraud and abuse. That staggering sum, if multiplied by the gross domestic product of the U.S., would mean an annual cost of more than $400 billion. Embezzlement, along with fraudulent statements and other corrupt acts such as bribery and bid rigging, represent the principal ways employees defraud their organizations. The term "occupational fraud and abuse" is broadly defined in the report as "the use of one's occupation for personal enrichment through the deliberate misuse or misapplication of the employing organization' s resources or assets." More than 2,608 fraud examiners participated in the study, which sought to estimate the probable cost of occupational fraud and abuse in the U.S.; determine characteristics of perpetrators of these offenses; profile data from victim organizations; and establish a uniform classification system for occupational fraud and abuse cases. The three costliest embezzlement schemes, which include larceny of cash, skimming, and fraudulent disbursements, are illustrated in the following scenarios. Although in some instances names have been changed to protect identities, the stories are true; and other versions of them are constantly being played out in organizations around the world. LARCENY OF CASH Median Loss $22,000 Some people would argue that auditors have no sense of humor. But Bill Guardo knows better. Guardo worked as a branch manager of a consumer loan finance company in New Orleans. For reasons that aren't exactly clear, he began stealing money from the finance company's bank deposits. One day Barry Ecker, the company internal auditor, decided on a whim to test Guardo's sense of humor. With a straight face, Ecker told Guardo, "Well, I'll see you Monday. We're going to pull an audit on your branch." With that, the internal auditor, who had no idea about Guardo's thefts, turned on his heels and left. Over the weekend, Guardo was left to stew in his own juices. He knew that his fraud would be easy to spot, since he had been stealing money from the deposits he took to the bank on a daily basis. On Sunday night, Guardo called the company president at home and confessed. He was immediately fired but returned the several thousand dollars he took. As a result, the company decided not to prosecute him. The moral of this story? The ol' fake audit gets them every time. The Guardo fraud represents one type of cash larceny: thefts from deposits. The other principle type is register theft. Larceny, according to Black's Law Dictionary, is "felonious stealing, taking and carrying, leading, riding, or driving away with another person's property, with the intent to convert it or to deprive the owner thereof." The key element in a larceny scheme is the fact that there is no effort to cover up the theft. Unlike the skimming schemes defined below, the cash has already been recorded on the books. In general, cash larceny schemes are not a high risk area for businesses. Presumably because adequate physical controls exist over the custody of cash in most organizations, these schemes accounted for only one percent of the total losses identified in the study. SKIMMING Median Loss $50,000 Brian Lee excelled as a top-notch plastic surgeon. Exuding a serious yet gentle manner, the 42-year old bachelor took quiet pride in his beautification efforts, which included nose jobs, liposuction, face lifts, and breast enhancements. Lee worked for a large physician-owned clinic in the southwestern U.S. In a bad year he took in $300,000 in salary and bonuses; a good year would net him $800,000. Somehow, that magnificent salary was not enough for Brian Lee. During one four-year stretch, the physician also skimmed several hundred thousand dollars from the clinic. When the issue came to light, the clinic contacted its law firm, who in turn contacted Doug Leclaire, a Certified Fraud Examiner, to conduct an independent investigation. Leclaire's interviews with the clinic staff turned up serious operational and control problems. It seemed that Dr. Lee would simply tell certain patients to pay him directly, bypassing the clinic's billing system altogether. Dr. Lee's fraud - like so many others - was detected entirely by accident. One of his patients, Rita Mae Givens, had paid him personally by check for a rhinoplasty procedure. She later decided to see if her insurance company would reimburse her for the operation, so she called the clinic for a copy of her bill. There was none. Doug Leclaire, following standard fraud examination procedures, saved the interview of Dr. Lee for last. Lee immediately confessed that he had a number of patients pay him directly. He was apologetic and even helped Leclaire piece together the evidence proving that Lee had embezzled several hundred thousand dollars from his professional colleagues. Dr. Lee furnished a motive for his misdeeds: simple greed. He was a driven man, much like his father and brother. Since Lee's schedule didn't permit much recreation, playing financial one-upmanship on his family became his hobby. It was important for him to have more money than his relatives. In the end, the greed of the clinic itself overcame reason. Lee was their top revenue producer, so the doctor was allowed simply to pay back the money he stole. No termination. No prosecution. No notoriety. But the clinic decided not to put Lee back into the arms of temptation, and they instituted controls to prevent future incidents. It's a good thing, apparently. The good doctor told Leclaire that, given the chance, "I would probably do it again." "Skimming" is the embezzlement of cash from an entity prior to its being recorded on the books. The cash skimmed can include sales, receivables, and refunds. Sales skimming can take the form of unrecorded sales, as in the case of Dr. Lee, or they can be understated, where an amount less than the full sale is reported to the company. In receivables skimming, the thefts are often those that are simply unrecorded on the books. When funds are diverted from accounts receivable, the amount owed can be reduced on the books by write-off schemes. Skimming schemes account for about a quarter of the losses in cash misappropriations, while fraudulent disbursements make up about three- fourths of the losses. It's possible that skimming schemes make up a smaller percentage because of their inherent nature: when someone purchases a product or service, or pays a bill, concealment of the transaction is absolutely necessary to avoid detection by the customer. FRAUDULENT DISBURSEMENTS Median Loss $75,000 Bruce Livingstone actually started the problem by taking his girlfriend on a trip at the company's expense. To disguise the disbursement, he unwisely named a senior female auditor as his traveling partner. The situation came to light when the bogus travel expense voucher landed on the desk of that very same senior female auditor for approval. Obviously, the voucher set off warning bells and buzzers, and the matter was referred to Harold Dore, Director of Internal Audit at the large medical college where this incident occurred. Dore wondered if he was looking at the tip of an iceberg and decided to interview Livingstone's assistant, Cheryl Brown, to see what she knew. Mysteriously, Cheryl canceled the interview at the last minute because her uncle had supposedly been shot in California. Brown left in such haste that she didn't even bother to pick up her paycheck. Dore smelled a rat. Livingstone's office was sealed to prevent any tampering of evidence, and Dore began a search of its contents. He found that Livingstone had been selling the school's dental tools to students from the back door and keeping the money for himself. When Dore began to inspect the accounting records - specifically the list of vendors in Livingstone' s office - the investigation took a surprising turn. Dore trimmed the vendor list to those with only a post office box and selected 50 of those invoices for examination. It didn't take long to focus in on one particular vendor, Armstrong Supply Company. The invoices supporting the disbursements to Armstrong ostensibly were for office supplies, but the invoices themselves looked fishy. They had all been produced on plain bond paper with a simple typewriter. The descriptions for the supplies purchased were vague. Then Dore found the smoking gun: blank invoices for Armstrong Supply Company under Cheryl's desk pad. Cheryl Brown confessed to her bogus invoice scheme, documenting some $63,000 in loot. Her thefts began only five months after she was hired. Cheryl claimed she and her husband were both addicted to drugs, which prompted their embezzlement scheme. Brown struck a plea bargain with the prosecutors, agreeing to pay the money back, serve a probated sentence, and serve a six-month term of house arrest. Fraudulent disbursements can take one of five principal forms. Brown chose the costliest type - the billing scheme. The other categories of fraudulent disbursements include payroll schemes, expense reimbursement schemes, check tampering, and register disbursement schemes. Fraudulent disbursement schemes provide a unique opportunity for the fraudster. The company is essentially "tricked" into making a legitimate- appearing disbursement. Unlike larceny or skimming schemes, the employee is not even physically required to take custody of the funds; the money can be converted indirectly by the employee through a third source, such as a shell company or an accomplice vendor. MANAGING THE RISKS The Report to the Nation on Occupational Fraud and Abuse offers two lessons for the fight against fraud. First, the ways employees embezzle money aren't necessarily complicated; they invariably employ larceny, skimming, or fraudulent disbursement methods to conduct their schemes. Second, the study discloses trends that can guide internal auditors in their detection and deterrence efforts. Fraudulent disbursements account for three-quarters of the losses, and the most expensive tend to be fraudulent disbursements through billing schemes. Therefore, internal auditors seeking to get the biggest bang for their investigative bucks should begin by making sure company vendors are for real. Since stealth is a key element in the modus operandi of occupational fraud and abuse, estimates about its prevalence and cost will probably never be completely known. The $400 billion figure may, therefore, be a gross understatement. The certainty is that, whether by skimming, larceny, or fraudulent disbursements, embezzlement is out there; and companies are paying the costs. • JOSEPH T. WELLS, CFE, CPA, is the founder and chairman of the 29,000 member Association of Certified Fraud Examiners in Austin, Texas. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners assumes sole copyright of any article published on ACFE.com. ACFE follows a policy of exclusive publication. Permission of the publisher is required before an article can be copied or reproduced. Requests for reprinting an article in any form must be e-mailed to: FraudMagazine@ACFE.com.