Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

Case

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

15

Countrywide Financial Corporation

and the Subprime Mortgage Debacle

Ronald W. Eastburn

Case Western Reserve University

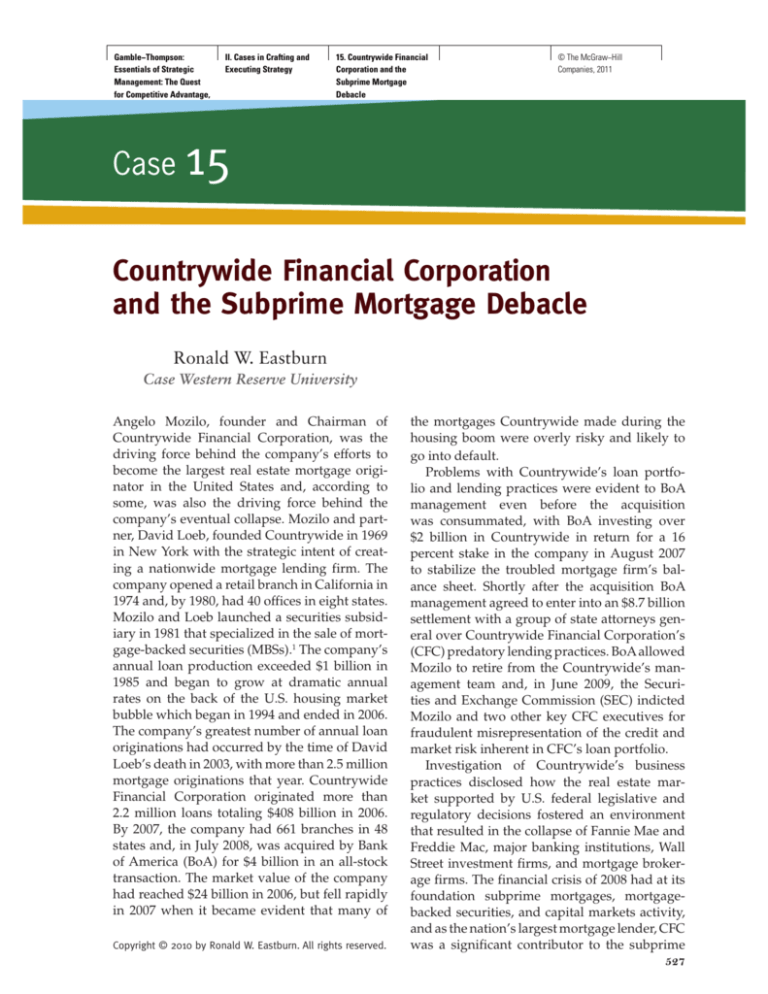

Angelo Mozilo, founder and Chairman of

Countrywide Financial Corporation, was the

driving force behind the company’s efforts to

become the largest real estate mortgage originator in the United States and, according to

some, was also the driving force behind the

company’s eventual collapse. Mozilo and partner, David Loeb, founded Countrywide in 1969

in New York with the strategic intent of creating a nationwide mortgage lending firm. The

company opened a retail branch in California in

1974 and, by 1980, had 40 offices in eight states.

Mozilo and Loeb launched a securities subsidiary in 1981 that specialized in the sale of mortgage-backed securities (MBSs).1 The company’s

annual loan production exceeded $1 billion in

1985 and began to grow at dramatic annual

rates on the back of the U.S. housing market

bubble which began in 1994 and ended in 2006.

The company’s greatest number of annual loan

originations had occurred by the time of David

Loeb’s death in 2003, with more than 2.5 million

mortgage originations that year. Countrywide

Financial Corporation originated more than

2.2 million loans totaling $408 billion in 2006.

By 2007, the company had 661 branches in 48

states and, in July 2008, was acquired by Bank

of America (BoA) for $4 billion in an all-stock

transaction. The market value of the company

had reached $24 billion in 2006, but fell rapidly

in 2007 when it became evident that many of

Copyright © 2010 by Ronald W. Eastburn. All rights reserved.

the mortgages Countrywide made during the

housing boom were overly risky and likely to

go into default.

Problems with Countrywide’s loan portfolio and lending practices were evident to BoA

management even before the acquisition

was consummated, with BoA investing over

$2 billion in Countrywide in return for a 16

percent stake in the company in August 2007

to stabilize the troubled mortgage firm’s balance sheet. Shortly after the acquisition BoA

management agreed to enter into an $8.7 billion

settlement with a group of state attorneys general over Countrywide Financial Corporation’s

(CFC) predatory lending practices. BoA allowed

Mozilo to retire from the Countrywide’s management team and, in June 2009, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) indicted

Mozilo and two other key CFC executives for

fraudulent misrepresentation of the credit and

market risk inherent in CFC’s loan portfolio.

Investigation of Countrywide’s business

practices disclosed how the real estate market supported by U.S. federal legislative and

regulatory decisions fostered an environment

that resulted in the collapse of Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac, major banking institutions, Wall

Street investment firms, and mortgage brokerage firms. The financial crisis of 2008 had at its

foundation subprime mortgages, mortgagebacked securities, and capital markets activity,

and as the nation’s largest mortgage lender, CFC

was a significant contributor to the subprime

527

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

528

Part Two:

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

Section D: Business Ethics and Social Responsibility

mortgage debacle. As the financial and credit

crisis continued to play out into 2009, BoA executives would need to ensure that lending practices at all of its subsidiaries would promote

homeownership in a manner that was in the

best interest of borrowers, investors in the secondary mortgage market, and the company’s

own long-term financial interests.

History of Mortgage Lending

in the United States

Before the Great Depression, home mortgage

instruments in the United States were typically

of short term (3–10 years) with loan-to-value

(LTV) ratios of about 60 percent. Loans at the

time were nonamortizing and required a balloon payment at the expiration of the term.

Mortgages were available to a limited client

base, with home ownership representing about

40 percent of U.S. households. Many of these

short-term mortgages went into default during

the Great Depression as homeowners became

unable to make regular payments or find new

financing to pay off balloon payments that

became due.

The United States government intervened in

the housing market in 1932 with the creation

of the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB). The

FHLB provided short-term lending to financial

institutions (primarily Savings and Loans) to

create additional funds for home mortgages.

Congress passed the National Housing Act of

1934 to further promote homeownership by

providing a system of insured loans that protected lenders against default by borrowers.

The mortgage insurance program established

by the National Housing Act and administered

by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA)

reimbursed lenders for any loss associated with

a foreclosure up to 80 percent of the appraised

value of the home. With the risk associated

with default on FHA-backed mortgage loans

reduced, lenders extended mortgage loan terms

to as long as 20 years and LTVs of 80 percent.

In 1938, Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA) was established as a government

corporation to facilitate a secondary market for

mortgages issued under FHA program guidelines. FNMA allowed private lenders to make

a greater number of FHA loans since loans

could be sold in the secondary market and did

not have to be held for the duration of the loan

term. New loans could be generated each time

the lender sold large bundles of loans to investors in the secondary market. The FNMA also

purchased conventional conforming mortgages

from lenders. Conventional conforming loans,

unlike FHA mortgages, were neither guaranteed nor insured by the federal government.

In 1968, FNMA was reconstituted as Fannie

Mae and became a publicly traded government sponsored enterprise (GSE). This move

allowed the financial activity of Fannie Mae to

be excluded from the U.S. federal budget and

transferred its portfolio of government insured

FHA mortgages to a wholly owned government corporation, Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae). Fannie Mae’s

portfolio of conforming loans remained on its

balance sheet.

In 1970, the Federal Home Loan Mortgage

Corporation (Freddie Mac) was chartered as a

GSE and operated in a manner similar to Fannie Mae (although its shares were not traded

until 1989). Freddie Mac pooled conforming

loans and created mortgage-backed securities

(MBSs) which were sold as shares of the pooled

loans to investors. The interest yield for these

agency securities was between AAA corporate

and U.S. treasury obligations, reflecting the

low risk of the securities. The development of

MBS vastly expanded the secondary market for

mortgage loans since investors could purchase

shares of a loan portfolio rather than purchase

an entire portfolio of intact loans.

The value of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae

to the capital market was related to the implicit

U.S. government guarantee of their debt and

MBS obligations. Their federal charter required

them to support the secondary market for residential mortgages, to assist mortgage funding

for low-and moderate-income families, and to

consider the geographic distribution of mortgage funding, including mortgage finance for

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

Case 15 Countrywide Financial Corporation and the Subprime Mortgage Debacle

underserved geographic sectors. An ancillary

benefit of the MBS product required national

standardization of underwriting procedures:

appraisals, borrower credit histories, and

guidelines for determining borrowers’ financial capacity to meet debt obligations. This

provided the foundation for real growth in the

mortgage market. The mortgage market in the

United States was also bolstered by the VA loan

program, which provided zero down payment

and low interest rates to veterans.

Mortgage Loan Originators

Prior to 1980, the vast majority of residential

home mortgage loans were made by savings

and loans institutions (S&Ls). These institutions

originated, serviced (collected payments and

managed escrow accounts for insurance and

property taxes), and retained the loans in their

own portfolios. S&Ls used the interest earned

from their portfolios of 30-year fixed rate home

mortgages to pay interest to savings account

holders—the yield spread between interest

earned on mortgages and interest paid on savings allowed S&Ls to earn consistent profits for

decades. The business model used by S&Ls collapsed when the Federal Reserve began to raise

short-term rates in the late 1970s to combat

inflation pressures, with interest paid on savings accounts now being greater than interest

earned on the low-rate mortgages originated

in the 1960s and early 1970s. The inverted

yield curve led to the failure of S&Ls across the

United States and an ensuing government bailout under the auspices of the Resolution Trust

Corporation (RTC).

The S&L crisis also led to the unbundling of

the mortgage business. Mortgage originations

and loan servicing became separate functions,

which pushed most new mortgage originations

into the secondary market as MBSs or collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). The ability for

mortgage originators to sell newly recorded

mortgages as MBSs and keep balance sheets

uncluttered with large loan portfolios allowed

the number of mortgage originators to increase

from 7,000 in 1987 to nearly 53,000 in 2006. The

529

Exhibit 1

Originations and Market Shares for the

Largest U.S. Mortgage Loan Originators,

2007 (dollar amounts in billions)

RANK ORIGINATOR

1

2

3

4

5

Countrywide

CitiMortgage

Wells Fargo

Mortgage

Chase Mortgage

Bank of America

Others

Total

2007

ORIGINATIONS MARKET

(IN BILLIONS)

SHARE

$408

272

15.5%

10.3

210

198

190

1,278

$2,628

7.9

7.5

7.2

48.6

100.0%

Source: As estimated by Countrywide Financial Corporation in

its 2007 10-K.

largest mortgage loan originators and their relative shares in 2007 are presented in Exhibit 1.

Expanding Home Ownership and

the American Dream

Beginning in the 1970s, social activist groups

began to point to statistics that indicated lenders

and the FHA were engaged in systematic racial

discrimination against minority consumers living in low-income neighborhoods (a practice

called “redlining”). Such activists mobilized

the U.S. Congress and the Carter Administration to enact the Community Reinvestment Act

(CRA) and the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act

(HMDA) to remedy social injustices in housing

and lending. In part, these acts required financial institutions to provide greater support to

low-income areas and provide more detailed

disclosures regarding mortgage terms.

Lenders whose disclosures uncovered redlining of low-income neighborhoods defended

their practices by pointing to the added risk

associated with making loans to those with

lower incomes, unstable employment histories,

high debt to income levels, or inadequate funds

for down payments. The Depository Institution

Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980

addressed such concerns by eliminating interest

rate caps and allowing lenders to charge higher

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

530

Part Two:

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

Section D: Business Ethics and Social Responsibility

or subprime rates to higher risk borrowers.

The Housing and Community Development

Act of 1981 created targets for lenders serving

low-income borrowers and allowed FHA borrowers with imperfect credit records to obtain

mortgage loans with LTVs of 90 to 95 percent.

In 1995 the Clinton Administration expanded

high LTV subprime loans under the CRA to

further expand homeownership for Americans

who were unable to qualify for mortgage loans

using conventional underwriting criteria.

The Residential Mortgage

Market in the United States in

the 2000s

The effects of the 60 years of federal legislation

promoting homeownership allowed nearly

70 percent of Americans to own a home by

2004. The value of new loan originations had

increased from $733 billion in 1994 to an all-time

high of $3.12 trillion in 2005, with large spikes

in loan origination values occurring in 2001

and 2003 before declining in 2004. Mortgage

originations had declined again in 2006 to $2.98

trillion. Exhibit 2 presents the value of total

U.S. mortgage originations and the percentage

of prime and subprime mortgage loan originations for 1994–2006. A graph representing the

percentage of American families owning their

own homes for the years 1944 through 2007 is

presented in Exhibit 3.

The Subprime Mortgage Market

A subprime mortgage was generally classified

as a mortgage loan to a borrower with a low

credit score, with a small down payment, or a

high debt-to-income ratio. In 1994 the subprime

market in the United States was approximately

$40 billion and represented approximately

6 percent of total mortgage loans originated.

The market for subprime mortgages grew rapidly and by year-end 2005 reached 37.6 percent

of total mortgage originations.

At the core of the growth of the subprime

market were relaxed underwriting standards.

As the appetite for MBSs on Wall Street rose,

mortgage brokers widened their sales net to

include relaxed documentation requirements

and impaired or limited credit histories. Many

loans were provided as “stated income loans,”

whereby the borrower did not have to prove

income (such loans became known among

mortgage underwriters as “liar loans”). The

Exhibit 2

Value of U.S. Home Mortgage Originations and Percentage of Prime versus

Subprime Mortgage Originations, 1994–2006 (dollar amounts in billions)

YEAR

TOTAL US ORIGINATIONS

(IN BILLIONS)

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

$ 773

639

785

859

1,450

1,310

1,048

2,215

2,885

3,945

2,920

3,120

2,980

PRIME MORTGAGE

ORIGINATIONS

(PERCENT OF TOTAL)

SUBPRIME MORTGAGE

ORIGINATIONS

(PERCENT OF TOTAL)

94.0%

86.9

83.2

78.3

84.0

83.2

81.5

87.9

88.4

86.5

68.1

62.4

63.7

Source: The 2007 Mortgage Market Statistical Annual, Inside Mortgage Finance.

6.0%

13.1

16.8

21.7

15.0

16.8

18.5

12.1

11.6

13.5

31.9

37.6

36.3

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

Case 15 Countrywide Financial Corporation and the Subprime Mortgage Debacle

EXHIBIT 3

531

Rate of Home Ownership in the United States, 1944–2007

80%

70

60

50

2007

2004

2001

1998

1995

1992

1989

1986

1983

1980

1977

1974

1971

1968

1965

1962

1959

1956

1953

1950

1947

1944

40

HOMEOWNERSHIP RATE

Source: U.S. Census Data 2007.

most popular mortgage products with consumers tended to be ARMs, which often included

introductory below-market rates. Below-market

“teaser” rates allowed for a low monthly payment in the first few years of the loan and then

were adjusted in line with market rates thereafter. Some real estate investors and homeowners exploited teaser rates to get into a home and

flip the property for a profit before the rate was

adjusted. Even if homeowners did not purchase

a home with the intention of flipping the house

for a profit, the rapid appreciation in home values during the early and mid-2000s allowed

overleveraged homeowners to sell their homes

and get out of high mortgage payments without great difficulty. However, once the housing

market slowed, the excesses of the subprime

mortgage market were exposed with resultant

increase in delinquencies, defaults, and foreclosures. In fact, in March 2007, the Mortgage

Bankers Association reported that 13 percent of

subprime borrowers were delinquent on their

payments by 60 days or more.

The Housing Bubble of the Mid-2000s

The expansion of homeownership increased

demand for both new and existing homes and

forced prices upward, creating a housing bubble that began in 1994 and peaked in 2006. In

2006, housing values had increased on average some 16 percent over the previous year. In

addition to opportunities to make quick profits

from buying and selling houses, rapid appreciation in home prices allowed many homeowners

to refinance or take out home equity loans to

make improvements to their homes, purchase

automobiles, or make other general purchases.

The housing bubble burst in 2007 when the

U.S. economy began to weaken, with declining demand for housing causing home prices to

plummet. With appreciation in home prices coming to an end, many consumers found their properties underwater (a negative equity position

caused by the mortgage balance being greater

than the fair market value of the property). Such

homeowners who had lost jobs or income during the recession or who had seen their payments on adjustable-rate mortgages rise were

faced with foreclosure since they had no hope

of selling their home at a price great enough to

pay off their mortgage balance. It was estimated

that 10 percent to 14 percent of all single-family

homes in the United States in 2007, regardless of

when they were purchased, had negative equity,

making one in seven single-family homes in the

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

532

Part Two:

Percent change from prior year

EXHIBIT 4

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

Section D: Business Ethics and Social Responsibility

S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices for Major U.S Cities, January 1988–May 2008

24%

21%

18%

15%

12%

9%

6%

3%

0%

–3%

–6%

–9%

–12%

–15%

–18%

–21%

10-City Composite

20-City Composite

24%

21%

18%

15%

12%

9%

6%

3%

0%

–3%

–6%

–9%

–12%

–15%

–18%

–21%

1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008

Source: Standard & Poor’s and Fiserv.

U.S. underwater.2 Exhibit 4 presents a graph

of percentage increases and decreases in home

prices as measured across major U.S. cities for

January 1988 through May 2008.

The U.S. Financial Crisis of 2008

With record numbers of mortgages in default,

a general liquidity crisis began to unfold which

led to an overall loss of confidence in the U.S.

financial system. The system unraveled in 2008

when losses at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

began to mount and American Insurance Group

(AIG) announced it was unable to back the

insurance guarantees that had supported the

Aaa to B bond ratings assigned to MBSs. Wall

Street firms had been packaging loans for sale

to investors across the world and now found

themselves holding securities with little value.

As financial institutions were forced to mark

their assets to market value, many, including

Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch,

Washington Mutual, and Wachovia, were either

forced to declare bankruptcy or be acquired by

stronger institutions. In September 2008, the

United States Treasury provided a bailout to

AIG3 and placed Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae

into conservatorships.

Countrywide Financial

Corporation

Countrywide Financial Corporation (CFC) was

founded in 1969 and on July 2, 2008, was sold

to Bank of America for $4 billion in an all-stock

transaction. Countrywide’s market value in late

2006 was $24 billion, but mounting mortgage

defaults and rumors of impending bankruptcy

had slashed the company’s market value by the

time it negotiated its buyout by BoA in January

2008. Angelo Mozilo, the founder and chairman

of Countrywide Financial, retired and received

a substantial severance package reported at $80

million to $115 million. In June 2009 the Securities and Exchange (SEC) indicted Mozilo for

fraudulent misrepresentation of credit and market risk inherent in the Countrywide mortgage

portfolio. Exhibit 5 provides key milestones

and events in Countrywide Financial’s corporate history.

Countrywide’s Business Segments

Countrywide was a diversified financial service provider engaged in mortgage lending and

other real estate finance–related businesses.

At its apex in 2006, Countrywide had $2.6 billion

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

Case 15 Countrywide Financial Corporation and the Subprime Mortgage Debacle

533

Exhibit 5

Key Milestones and Events in Countrywide Financial Corporation’s History

1969

1974

1980

1981

1985

1984

1986

1987

1993

1996

1998

1999

2000–2005

2001

2002

2006

2007–Jan. 31

2007–April 26

2007–July 24

2007–Aug. 16

2007–Aug. 22

2007–Sept. 9

2007–Sept. 18

2007–Oct. 23

2007–Oct. 26

2007–Nov. 20

2008–Jan. 11

July 2, 2008

Angelo Mozilo and David Loeb launch Countrywide Credit Industries in New York with the

aim to one day provide home loans nationwide. Countrywide goes public in September,

trading at less than $1 per share. Mozilo and Loeb relocate Countrywide to Los Angeles.

Countrywide opens first retail office in Whittier, Califiornia.

Countrywide has 40 retail offices across eight states.

Mozilo and Loeb launch subsidiary Countrywide Securities Corp. to sell mortgage-backed

securities.

Countrywide’s ticker symbol, CCR, opens on the New York Stock Exchange on October 7.

Stock closes at $2 a share.

The value of loans serviced by Countrywide hits $1 billion. The company begins using

computers to originate home loans.

Loan production tops $1 billion.

Loan production soars to $3.1 billion. Countrywide begins servicing loans originated

by mortgage lenders.

Countrywide’s mortgage-lending reach grows amid a housing and mortgage refinancing

boom. Originations increase by 265 percent from 1992.

Company launches business units focused on home equity loans (HELOC) and home

loans to borrowers with weak credit histories (subprime).

Mozilo named chief executive in February.

Mozilo named chairman in March.

Countrywide benefits from another housing and refinancing boom coupled with

historically low interest rates.

Countrywide acquires Treasury Bank N.A. It goes on to become Countrywide Bank FSB.

Company becomes Countrywide Financial Corp. on November 13, with new stock ticker:

CFC.

CFC reports fourth-quarter earnings soar 73 percent to $638.9 million on January 31,

as profits climb 29 percent to $2.59 billion.

CFCs fourth-quarter profits fall 2.7 percent and revenue slips 6 percent. The lender blames

falling home prices and fewer home sales for a drop in new mortgage loans.

CFC first-quarter profits tumble 37 percent; revenue shrinks by 15 percent. Mounting

mortgage defaults force CFC to increase loan reserve $81 million and take a $119 million

write-down for declining value of some loans on its books. Mozilo blames deteriorating

credit in the subprime mortgage market.

CFC second-quarter profit declines by nearly a third and revenue dips 15 percent.

A worsening credit crisis sparked by the collapse of the subprime mortgage market and

ongoing housing woes force CFC to draw down $11.5 billion from its credit lines.

CFC raises $2 billion by selling a 16 percent stake to Bank of America.

Under pressure to reduce costs, CFC reports it will cut as many as 12,000 jobs.

Management takes steps to shift lending activity through its banking arm and stop selling

subprime loans.

Speaking at an investor conference, Mozilo declares the company will “come out stronger

in the long run, just as we have often done in the past.”

Countrywide outlines stepped-up efforts to help borrowers in trouble avoid foreclosures.

Countrywide reports a third-quarter $1.2 billion loss, the first quarterly loss for the

company in 25 years. Still, Mozilo says he’s “bullish” about the long-term prospects of the

company and says it expects to be profitable in the fourth quarter and in 2008.

Rumors surface that CFC may seek bankruptcy protection. CFC issues statement declaring

it has ample capital, access to cash and is well positioned to benefit from the financial

turmoil rocking the mortgage sector.

BofA announces acquisition of CFC, subject to shareholder and government approvals,

for $4 billion in an all stock transaction.

Countrywide officially became a wholly owned subsidiary of Bank of America.

Source: Countrywide Financial Corporation SEC Filings. Annual Reports and press releases.

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

534

Part Two:

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

Section D: Business Ethics and Social Responsibility

in net earnings and $200 billion in total assets.

The business was managed through five business segments: mortgage banking, banking, capital markets, insurance, and global operations.

•

Mortgage banking. The origination, purchase, sale, and servicing of noncommercial

mortgage loans nationwide.

•

Banking. Gathered retail deposits used to

invest in mortgage loans and home equity

lines of credit, sourced primarily through

the mortgage banking operation as well as

through purchases from nonaffiliates.

•

Capital markets. The institutional brokerdealer business which specialized in trading and underwriting mortgage-backed

securities. The business unit also traded

derivative products and U.S. Treasury securities, provided asset management services,

and originated loans secured by commercial real estate. Within this segment CFC

managed the acquisition and disposition of

mortgage loans on behalf of the Mortgage

Banking Segment.

•

Insurance. The property, casualty, life, and

disability insurance underwriting provider.

The business unit also included reinsurance

coverage to primary mortgage insurers.

•

Global operations. Licensed proprietary

technology to mortgage lenders in the

United Kingdom and handled some of

the company’s administrative and loan

servicing functions through operations

in India.

Mortgage banking was Countrywide’s core

business, generating 48 percent of its 2006 pretax earnings. A summary of CFC’s mortgage

loan production for 2003 through 2007 is presented in Exhibit 6.

Countrywide Loan Originations and

Market Share

CFC held the largest market share among U.S.

mortgage originators in 2007 with 15.5 percent

of all originations, up considerably from

2001 when CFC held a 6.6 percent share. As

shown Exhibit 7, CFC originated 35,000 loans

in 1990, which were more or less evenly split

between conventional and VHA/VA loans. It

was not until the 1995–1996 period that CFC

began to underwrite home equity and subprime loans. The company’s loan originations

peaked in 2003 with over 2.5 million loans

being originated. In 2005, approximately 11

percent of Countrywide’s loan originations

were subprime and CFC home equity line

of credit loans (HELOCs) reached a peak in

2006. Many of Countrywide’s HELOCs were

part of so-called 80/20 purchase loans that

provided borrowers with 100 percent financing. Countrywide’s no-down-payment loans

allowed borrowers to piggyback a 20 percent

LTV home equity line of credit loan on top

of a conventional nonconforming 80 percent

LTV mortgage. CFC’s originations of conventional nonconforming loans began in 2002

and closely matched the company’s origination of HELOCs. A significant portion of

Countrywide’s mortgage loan originations

were sold into the secondary mortgage markets as MBSs.

Countrywide’s Financial and

Strategic Performance

Between 2002 and 2007, Countrywide’s assets

grew from $58 million to $211 million, and its

revenues rose from $4.3 billion to $11.4 billion.

The mortgage firm’s operating earnings grew

from $1.3 million in 2002 to $4.3 million in

2006. After recording record breaking financial

results for five consecutive years, CFC reported

its first-ever loss in 2007. The dramatic reversal in CFC’s financial performance was largely

a result of its strategy keyed to the origination

of subprime mortgages and no-down-payment

loans. The hidden risk of default, foreclosures,

and downgrades of such high-risk loans was

masked while real estate values rose through

2006. Exhibit 8 presents selected financial data

for Countrywide Financial Corporation for

2003 through 2007.

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

Case 15 Countrywide Financial Corporation and the Subprime Mortgage Debacle

535

Exhibit 6

Countrywide Financial Corporation’s Loan Production by Segment and Product, 2003–

2007 (in millions)

MORTGAGE LOAN PRODUCTION

YEARS ENDED DECEMBER 31,

2007

Segment:

Mortgage Banking

Banking Operations

Capital Markets—

conduit acquisitions

from nonaffiliates

Total Residential

Mortgage Loans

Commercial Real

Estate

Total mortgage loans

Product:

Prime Mortgage

Prime Home Equity

Nonprime Mortgage*

Commercial Real

Estate

Total mortgage loans

2006

2005

2004

2003

$ 385,141

18,090

$ 421,084

23,759

$ 427,916

46,432

$ 317,811

27,116

$ 398,310

14,354

5,003

17,658

21,028

18,079

22,200

408,234

462,501

495,376

363,006

434,864

7,400

5,671

3,925

358

—

$ 415,634

$ 468,172

$ 499,301

$ 363,364

$ 434,864

$ 356,842

34,399

16,993

$ 374,029

47,876

40,596

$ 405,889

44,850

44,637

$ 292,672

30,893

39,441

$ 396,934

18,103

19,827

7,400

5,671

3,925

358

—

$ 415,634

$ 468,172

$ 499,301

$ 363,364

$ 434,864

* Countrywide Financial did not use the term “subprime.” The term “nonprime” was used to categorize subprime mortgages in the

company’s financial filings.

Source: Countrywide Financial Corporation 2007 10-K.

Incentive Compensation at

Countrywide Financial

Executive Compensation at

Countrywide Financial Corporation

Compensation expense represented approximately 55–60 percent of total expenses between

2003 and 2007. Compensation included employees’ base salary, benefits expense, payroll taxes,

and incentive pay. Countrywide’s compensation system based incentive pay on loan originations and did not include loan defaults as a

performance compensation metric. Many lending institutions frowned upon incentive plans

linked only to loan originations since loan performance ultimately determined the strength of

a loan portfolio. Exhibit 9 provides a graph of

incentive pay as a percentage of base pay for all

CFC employees during 1992 through 2007.

The compensation for Mozilo for 2006 and 2007

is shown in Exhibit 10. Mozilo’s compensation

listed in the table does not include perquisites

that amounted to approximately $108,000 per

year and included company cars, country club

memberships, the personal use of corporate aircraft, insurance, and a financial planning program. Mozilo also exercised $121 million of stock

options in 2007 and reportedly stood to collect a

reported windfall of $80 million to $115 million

on the $4 billion sale of the company to BofA, as

part of his severance package. However, after facing heavy criticism from lawmakers, Mozilo said

he would forfeit $37.5 million tied to the deal.

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

536

Part Two:

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

Section D: Business Ethics and Social Responsibility

Exhibit 7

Countrywide Financial Corporation Loan Originations, 1990–2007 (in thousands)

YEAR

CONVENTIONAL

CONFORMING

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

19

23

64

192

316

176

192

190

232

529

359

327

994

1510

822

767

709

1088

CONVENTIONAL

NONCONFORMING

FHA/VA

266

493

430

712

649

313

16

17

24

42

67

72

125

144

162

191

132

119

157

196

102

80

90

138

HELOC

2

8

20

41

54

91

119

290

292

392

493

581

330

SUBPRIME

TOTAL LOAN

ORIGINATIONS

2

9

16

25

43

52

44

95

219

254

227

85

35

40

88

234

383

250

327

363

451

799

625

617

1751

2586

1965

2306

2256

1954

Source: Countrywide Financial Corporation 10-Ks, various years.

Exhibit 8

Selected Consolidated Financial Data for Countrywide Financial Corporation, 2003–2007

(in thousands, except per share data)

YEARS ENDED DECEMBER 31,

2007

Statement of Operations

Data:

Revenues:

Gain on sale of loans

and securities

Net interest income after

provision for loan losses

Net loan servicing fees

and other income (loss)

from MSRs and retained

interests

Net insurance premiums

earned

Other

Total revenues

Expenses:

Compensation

Occupancy and other

office

2006

2005

2004

2003

$2,434,723

$5,681,847

$4,861,780

$4,842,082

$5,887,436

587,882

2,688,514

2,237,935

1,965,541

1,359,390

909,749

1,523,534

1,300,655

1,171,433

1,493,167

953,647

465,650

782,685

(463,050)

732,816

605,549

574,679

470,179

510,669

462,050

6,061,437

11,417,128

10,016,708

8,566,627

7,978,642

4,165,023

4,373,985

3,615,483

3,137,045

2,590,936

1,126,226

1,030,164

879,680

643,378

525,192

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

Case 15 Countrywide Financial Corporation and the Subprime Mortgage Debacle

Exhibit 8

537

(continued)

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

Insurance claims

Advertising and

promotion

Other

525,045

449,138

441,584

390,203

360,046

321,766

1,233,651

260,652

969,054

229,183

703,012

171,585

628,543

103,902

552,794

Total expenses

7,371,711

7,082,993

5,868,942

4,970,754

4,132,870

(1,310,274)

4,334,135

4,147,766

3,595,873

3,845,772

(606,736)

1,659,289

1,619,676

1,398,299

1,472,822

$ (703,538)

$2,674,846

$2,528,090

$2,197,574

$2,372,950

$(2.03)

$(2.03)

$0.60

$4.42

$4.30

$0.60

$4.28

$4.11

$0.59

$3.90

$3.63

$0.37

$4.44

$4.18

$0.15

$8.94

$42.45

$34.19

$37.01

$25.28

(0.30%)

(4.57%)

N/M

1.28%

18.81%

13.49%

1.46%

22.67%

13.81%

1.80%

23.53%

9.53%

2.65%

34.25%

3.39%

$1,476,203

$1,298,394

$1,111,090

$838,322

$644,855

$415,634

$468,172

$499,301

$363,364

$434,864

$375,937

$403,035

$411,848

$326,313

$374,245

(Loss) earnings before

income taxes

(Benefit) provision for

income taxes

Net (loss) earnings

Per Share Data:

(Loss) earnings

Basic

Diluted

Cash dividends declared

Stock price at end of

period

Selected Financial Ratios:

Return on average assets

Return on average equity

Dividend payout ratio

Selected Operating Data

(in millions):

Loan servicing portfolio(1)

Volume of loans

originated

Volume of Mortgage

Banking loans sold

(1) Includes warehoused loans and loans under subservicing agreements.

DECEMBER 31,

Selected Balance Sheet

Data at End of Period:

Loans:

Held for sale

Held for investment

Securities purchased

under agreements to

resell, securities

borrowed and federal

funds sold

Investments in other

financial instruments

Mortgage servicing rights,

at fair value

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

$ 11,681,274

98,000,713

$ 31,272,630

78,019,994

$ 36,808,185

69,865,447

$37,347,326

39,661,191

$24,103,625

26,375,958

109,681,987

109,292,624

106,673,632

77,008,517

50,479,583

9,640,879

27,269,897

23,317,361

13,456,448

10,448,102

28,173,281

12,769,451

11,260,725

9,834,214

12,647,213

18,958,180

16,172,064

—

—

—

continued

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

538

Part Two:

Exhibit 8

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

Section D: Business Ethics and Social Responsibility

(continued)

2007

Mortgage servicing

rights, net

Other assets

2006

—

Total assets

Deposit liabilities

Securities sold under

agreements to repurchase

Notes payable

Other liabilities

Shareholders’ equity

Total liabilities and

shareholders’ equity

2005

—

12,610,839

2004

8,729,929

2003

6,863,625

45,275,734

34,442,194

21,222,813

19,466,597

17,539,150

$211,730,061

$199,946,230

$175,085,370

$128,495,705

$97,977,673

$60,200,599

$55,578,682

$39,438,916

$20,013,208

$9,327,671

18,218,162

97,227,413

21,428,016

14,655,871

42,113,501

71,487,584

16,448,617

14,317,846

34,153,205

76,187,886

12,489,503

12,815,860

20,465,123

66,613,671

11,093,627

10,310,076

32,013,412

39,948,461

8,603,413

8,084,716

$211,730,061

$199,946,230

$175,085,370

$128,495,705

$97,977,673

The 2007 capital ratios reflect the conversion of Countrywide Bank’s charter from a national bank to a federal savings bank. Accordingly, the ratios for 2007 are for Countrywide Bank calculated using OTS guidelines and the ratios for the prior periods are calculated

for Countrywide Financial Corporation in compliance with the guidelines of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Bank.

Source: Countrywide Financial Corporation 2007 10-K.

Charges of Predatory Lending

Practices at Countrywide

Predatory loans were generally considered to be

any loan that a borrower would have rejected

with full knowledge and understanding of the

terms of the loan and the terms of alternatives

EXHIBIT 9

available to them. Predatory lenders typically

relied on a range of practices including deception, fraud, and manipulation to convince borrowers to agree to loan terms that were unethical

or illegal. Countrywide Financial was charged

with engaging in predatory lending practices

in the case Department of Legal Affairs (Florida) v.

Incentive Pay as Percentage of Base Pay for All Employees of Countrywide Financial Corporation, 1992–2007

Incentive as % base

120%

100%

80%

60%

40%

20%

0%

1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006

Source: Countrywide Financial Corporation 10-Ks, various years.

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

Case 15 Countrywide Financial Corporation and the Subprime Mortgage Debacle

539

Exhibit 10

Angelo Mozilo’s Comensation at Countrywide Financial Corporation,

2006–2007

COMPENSATION COMPONENTS

Base salary

Annual incentive

Equity awards

Total

Exercised options

2006

2007

$ 2,900,000

20,461,473

19,012,000

$ 42,373,473

—

$

1,900,000

0

10,000,036

$ 11,900,036

$121,502,318

% CHANGE

(34%)

(100%)

(47%)

(72%)

n/a

Note: n/a ⫽ not applicable.

Source: Countrywide Financial Corporation 2007 10-K.

Countrywide Financial Corp. et al., filed June 30,

2008). Specific illegal practices alleged in the

case included:

1. CFC did not follow its own underwriting

standards.

2. CFC did not follow industry underwriting

standards.

3. CFC placed borrowers into loans they

knew they could not afford.

4. CFC failed to properly disclose loan terms

including

a. Misrepresenting duration of “teaser

rates.”

b. Misrepresenting adjustable rates as fixed

rates.

c. Misrepresenting the manner and degree

of payment increases after initial fixed

rate period.

d. Not disclosing that low teaser rates

would expire and dramatically increase

resulting payments that might be far

beyond borrower’s means.

5. CFC knowingly placed borrowers in inappropriate mortgages.

6. CFC provided underwriters with bonuses

based upon volume of mortgages

approved.

Countrywide portrayed itself as underwriting mainly prime quality mortgages using rigorous underwriting standards. Concealed from

shareholders was the true Countrywide, an

increasingly reckless lender assuming greater

and greater risk. From 2005 to 2007, Countrywide engaged in an unprecedented expansion

of its underwriting guidelines and was writing riskier and riskier loans, according to the

SEC. A series of internal e-mails confirmed that

senior executives knew that defaults and delinquencies would rise. In particular, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) pointed

to Countrywide’s increased origination of payoption mortgages, which allow borrowers to

choose their monthly payments even if they

did not cover the entire interest amount. While

CFC maintained these loans were prudently

underwritten, the SEC stated that Mozilo wrote

in an e-mail that there was evidence that borrowers were lying on their applications and

many would be unable to handle the eventual

higher payments.

Angelo Mozilo’s Internal E-mails at

Countrywide Financial Corporation

In June 2009, the SEC filed civil-fraud charges

against three former Countrywide executives,

including Angelo Mozilo. The complaint cited

e-mails sent by Mozilo as evidence of fraudulent behavior at Countrywide Financial. The

statements below are from excerpts of Mozilo

e-mails released by the SEC.

April 13, 2006: To Sambol (Countrywide Financial Corporation President)

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

540

Part Two:

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

Section D: Business Ethics and Social Responsibility

and others to address issues relating to

100 percentage financed loans, after Countrywide had to buy back mortgages sold to

HSBC because HSBC contended they were

defective:

Loans had been originated . . . throughout

channels with disregard for process and

compliance with guidelines.

April 17, 2006: To Sambol concerning

Countrywide’s subprime 100 percent

financing 80/20 loans. (The term “FICO”

refers to credit scores used to assess borrower’s creditworthiness.)

In all my years in business I have never seen

a more toxic product. It’s not only subordinated to the first, but the first is subprime.

In addition, the FICOs are below 600, below

500 and some below 400. With real estate

values coming down . . . the product will

become increasingly worse. There has to

be major changes in this program, including substantial increases in the minimum

FICO. . . . Whether you consider the business milk or not, I am prepared to go without milk irrespective of the consequences to

our production.

Sept. 26, 2006: Following a meeting with

Sambol the previous day about Pay-Option

ARM loan portfolio:

We have no way, with any reasonable certainty, to assess the real risk of holding these

loans on our balance sheet. . . . The bottom

line is that we are flying blind on how these

loans will perform in a stressed environment of high unemployment, reduced values and slowing home sales . . . timing is

right . . . to . . . sell all newly originated pay

option and begin rolling off the bank balance sheet, in an orderly manner.

Countrywide’s VIP Loan Program

Countrywide maintained a VIP program that

waived points, lender fees, and company borrowing rules for “FOAs”—Friends of Angelo,

a reference to CFC’s Chief executive Angelo

Mozilo. While the VIP program also serviced

friends and contacts of other CFC executives, it

is believed the FOAs made up the biggest subset.

Some FOAs were individuals who might have

been in position to aid the company through

regulatory and compliance matters or who may

have been able to keep the subprime market

viable through favorable legislation. Countrywide’s ethics code barred directors, officers, and

employees from “improperly influencing the

decisions of government employees or contractors by offering or promising to give money,

gifts, loans, rewards, favors, or anything else

of value.” Also, federal employees were prohibited from receiving gifts offered because of

their official position, including loans on terms

not generally available to the public. Senate

rules prohibit members from knowingly receiving gifts worth $100 or more in a calendar year

from private entities that, like CFC, employed a

registered lobbyist.

Among the most noteworthy recipients of

Countrywide VIP loans were two prominent

U.S. Senators, two former Cabinet members, and

a former Ambassador to the United Nations. In

2003 and 2004, Senators Christopher Dodd, a

Democrat from Connecticut and chairman of

the Senate Banking Committee,4 and Kent Conrad, a Democrat from North Dakota, chairman

of the Senate Budget Committee and a member

of the Senate Finance Committee, refinanced

properties through CFC’s VIP program.

Other participants in the VIP program

included former Secretary of Housing and

Urban Development (HUD) Alphonso Jackson,

former Secretary of Health and Human Services

Donna Shalala, and former U.N. ambassador

and Assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke. Jackson was deputy HUD secretary in

the Bush administration when he received the

loans in 2003. Shalala, who received two loans

in 2002, had by then left the Clinton Administration for her current position as president of

the University of Miami. Holbrooke, whose

stint as U.N. ambassador ended in 2001, was

also working in the private sector when he and

his family received VIP loans. Mr. Holbrooke

was an adviser to Hillary Clinton’s presidential 2008 campaign. James Johnson, who had

been advising presidential candidate Barack

Obama on the selection of a running mate in

Gamble−Thompson:

Essentials of Strategic

Management: The Quest

for Competitive Advantage,

Second Edition

II. Cases in Crafting and

Executing Strategy

15. Countrywide Financial

Corporation and the

Subprime Mortgage

Debacle

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2011

Case 15 Countrywide Financial Corporation and the Subprime Mortgage Debacle

2008, resigned from the Obama campaign after

The Wall Street Journal reported that he received

CFC loans at below-market rates.

Bank of America’s Attempts

to Salvage Its Acquisition

of Countrywide Financial

Corporation

Almost as soon as the acquisition closed, BofA

entered into an $8.7 billion settlement agreement with a group of state attorneys general

over CFC’s lending practices. BofA also agreed

to modify the loans of certain CFC borrowers

with subprime and pay-option mortgages. In

the first four months following the settlement

agreement, BofA contacted more than 100,000

potentially eligible borrowers, twice the

requirement in the agreement, and completed

modifications for more than 50,000 of them.

The settlement was the largest predatory lending settlement in U.S. history as of 2009.

541

In March 2009, American International

Insurance Group (AIG) sued BoA over Countrywide’s business practices, alleging the company misrepresented the risk associated with

the sale of mortgages totaling over $1 billion.

AIG claimed that CFC had falsely represented

that its mortgages were in compliance with its

AIG underwriting standards.

BofA retired the Countrywide brand name

in 2009 as it worked to distance itself from the

brand and CFC’s business practices. According

to California Attorney General Edmund Brown,

“CFC lending practices turned the American

dream into a nightmare for tens of thousands of

families by putting them into loans they could

not understand or ultimately could not afford.”5

Going forward, Bank of America senior managers would need to develop a strategic approach

to ensure that its mortgage lending practices

promoted homeownership in a manner that

was in the best interest of borrowers, investors in the secondary mortgage market, and the

company’s own long-term financial interests.

Endnotes

1

These products were developed following the Savings and Loan

(S&L) crisis of the 1980s and converted the actual mortgage into pools

of mortgages, which enabled institutions to invest and trade a marketable security. MBSs were also known as collateralized debt obligations.

2

3

Moody’s Economy.com.

AIG’s core business as the world’s largest general insurer was sound.

However, AIG’s CDO insurance business, while a very small part of

their overall business, has brought the firm close to bankruptcy. As for

AIG’s global reach, it was far too extensive and a default would have

brought down other financial institutions across the world markets.

4

CFC had contributed a total of $21,000 to Dodd’s campaigns

since 1997.

5

As quoted in Frank D. Russo, “Attorney General Brown Announces

Largest Predatory Lending Settlement in History,” California Progress

Report, accessed at http://www.californiaprogressreport.com/2008/10/

attorney_genera_3.html (accessed September 5, 2009).