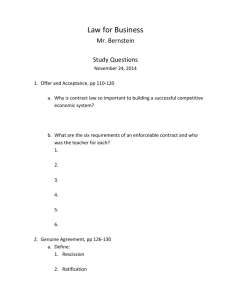

C Czarnikow Ltd v Koufos (The Heron II) [1967]

advertisement

![C Czarnikow Ltd v Koufos (The Heron II) [1967]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008083605_1-e8e87a52fe5bb820fbc00ac315eba0df-768x994.png)