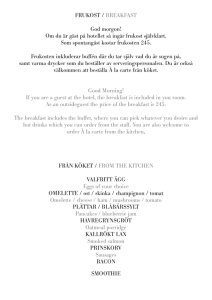

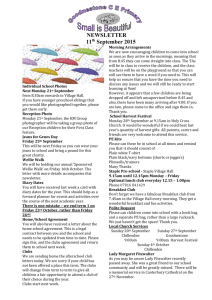

Scoping study for Healthy Food for All on Breakfast Clubs

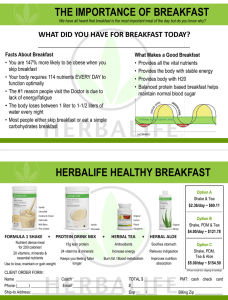

advertisement