Debits and Credits for Assets, Liabilities, and Equity

advertisement

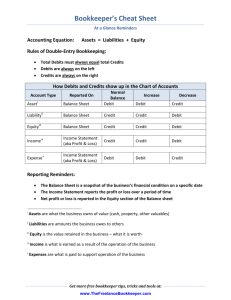

Debits and Credits for Assets, Liabilities, and Equity Accountants analyze transactions using debits and credits. Whether a debit or credit represents an increase or decrease depends on the type of account being considered. To refresh your memory, the accounting equation is Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ Equity The two sides of the accounting equation must always be equal because they are two views of the same company. The left-hand side shows the economic resources controlled by a business (the assets), and the right-hand side shows the claims against these resources (liabilities and owners’ equity). Another way to view this equality is that the company must get money to buy its assets, and the right-hand side of the equation shows the origin of the financing used to get the money to buy the assets. Analysis of the four transactions below illustrates that proper accounting ensures that the accounting equation is always true. Accounting Equation Analysis of Four Transactions Business Activity Effect in Terms of the Accounting Equation: (Transaction)Assets =Liabilities + Owners’ Equity 1.Owner invested $700,000 cash. +700,000 (Cash) +700,000 (Paid-in Capital) 2.Borrowed $300,000 cash +300,000 (Cash) +300,000 from the bank(Bank Loan Payable) 3.Purchased land for $50,000 and a building for $400,000 by paying $100,000 cash and incurring a $350,000 mortgage –100,000 (Cash) +350,000 +50,000 (Land) (Mortgage Payable) +400,000 (Buildings) 4.Purchased equipment for $650,000 cash –650,000 (Cash) +650,000 (Equipment) Note that after every transaction, the accounting equation is still in balance. Although some of the transactions can get pretty complex, such as transaction (3), which involves four accounts, the necessary equality of the accounting equation forces us to continue our analysis of the Copyright2011 - www.MyAccountingTeacher.com transaction until we have identified all of its effects. Although it makes conceptual sense, the spreadsheet analysis format based on the accounting equation can be cumbersome. Suppose that a company has 200 accounts and 10,000 transactions each month; the resulting spreadsheet would quickly grow to unwieldy size. When the process underlying modern bookkeeping was formalized 500 years ago, maintaining a 10,000-row by 200-column spreadsheet, by hand, was just not practical. In addition, the realities of manual arithmetic made it desirable to have a system based as much as possible on addition rather than on one requiring a constant switching between addition and subtraction. The system devised 500 years ago to deal with these practical realities is elegant in its simplicity. All transactions relating to a specific item are recorded in a single account, which can be visualized as a page in a book. Increases are represented by writing transaction amounts on one side of the account; decreases are represented by writing amounts on the other side. These accounts are often presented in the form of T accounts as illustrated with the following examples: Cash Loans Payable Paid-in Capital --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------||| ||| ||| ||| The account title (Cash, for example) appears at the top of the T account. Transaction amounts are recorded either on the left side or on the right side of the T account. Instead of using the terms left and right to indicate which side of a T account is affected, accountants use their own special terminology. Debit is used to indicate the left side of a T account and credit is used to indicate the right side of a T account. The T account formulation, with debits on the left and credits on the right, takes care of two of the practical difficulties presented by the manual use of the spreadsheet format. First, by grouping all the transaction amounts dealing with a specific item into one account, with each account basically being the equivalent of a page in a book, it is now possible to have an unlimited number of accounts, each as a separate page. This is much more workable if one is operating the system manually (as they did 500 years ago when this was invented) than being forced to construct a bigger and bigger spreadsheet each time an account is added. Second, the arithmetic problem of switching back and forth from addition to subtraction is solved because the total amount in the account is computed by adding all the debit amounts, adding all the credit amounts, and then performing just one subtraction to find the difference. One thing missing thus far from this description of debits, credits, and T accounts is a selfchecking mechanism analogous to the accounting equation. The solution for this deficiency Copyright2011 - www.MyAccountingTeacher.com is the simple insight that makes the debit and credit framework so useful that it has survived, basically unchanged, for 500 years. By convention, all increases in assets are represented as debits (on the left side of the account) and decreases are represented as credits (on the right side of the account). For liabilities and equities, just the opposite convention is used: increases are represented by credits and decreases are represented by debits. These conventions are summarized below. AssetLiabilityEquity ------------------------------ ------------------------------ --------------------------||| debit|creditdebit | creditdebit | credit + | - - | + - | + ||| When these debit and credit conventions are used, maintaining the equality of the accounting equation can be done just by making sure that debits equal credits. Thus, when accountants analyze even complex transactions, they rarely refer to the accounting equation because they know that the simple rule of “debits = credits” ensures that the accounting equation is always in balance. FYI When accountants talk among themselves, they often use the terms debit and credit as verbs. For example, to “debit Cash” means to record the fact that cash has increased. To “debit Loans Payable” means that the recorded amount of a loan has decreased. Copyright2011 - www.MyAccountingTeacher.com