Doriot told his Harvard - The High Income Factor

2

H is idea defied financial logic. It would take too long, the risks were too high, and the rewards too small. Wall Street experts said it’d never work.

But, never say never. Proving the naysayers wrong, this man watched a single investment earn over 500,000 percent — seeing that investment more than double every year for nine straight years. It’s a mind-boggling number. To put it in perspective, if you invested $1,000, a 500,000 percent increase would yield a $5 million windfall.

That’s impressive, considering this was an idea that wasn’t supposed to work.

That alone would be a great ending to the story, but it marked just the beginning of something that would turn this man’s seemingly strange idea into industry standard practice. He changed the way we seek opportunities, the way we calculate risks, and the way we make serious money. Who is this guy who could completely unravel conventional Wall Street wisdom?

Well, it took an

“ the following year, enlisted in the U.S. Army. A lieutenant colonel and chief of military planning for the Quartermaster Corps, Doriot put his manufacturing skills to good use by improving military equipment, which earned him a promotion to brigadier general. His improvements included better shoes, cold-weather gear, uniforms, tents, sunscreens, insecticides, freeze-dried foods, and powdered coffee.

Then, due to a shortage of metallic armor in

1942, he was called to oversee the invention of a lightweight plastic armor, and he succeeded in developing a fiberglass-plastic combination that was named “Doron” in his honor.

After being discharged from the Army, Doriot returned to Harvard in 1946, where he continued

Doriot told his Harvard students, ‘I want my money to do things that have never been done before.’

unconventional man, one with diverse skills acquired from the military, manufacturing, business, and academia, spurring a visionary who forever changed the capital markets.

His name is Georges Doriot, and while the name may not be familiar (though some will know him as the founder of INSEAD, Europe’s top business school), he is considered a leading light of the most productive and profitable area of investing — venture capitalism.

Born in 1899 in France, Doriot grew up immersed in the world of small business start-ups and manufacturing. His father was an engineer who helped invent the first car for the start-up

Peugeot Motor Company.

After a short stint in the French army, Doriot came to America in 1921 to earn an MBA.

Although he dropped out of the program, he went on to become one of Harvard’s most influential professors, whose 40-year teaching span inspired some of the most prominent executives of the day, including Fred Smith, founder of Federal Express, and Ralph Hoagland, co-founder of CVS Corp.

In 1940, he received his U.S. citizenship and,

” to teach his highly praised manufacturing course. Rather than focusing on teaching the industrial side of business, though, he spent most of the time talking about his interests in other aspects of enterprise, high-level executive problems, and globalization.

And it was through these discussions that an idea was sparked, one so innovative, it would fundamentally change the economy.

From Idea to Innovation

Doriot understood the importance of globalization and innovation for economic growth.

He showed his students how railroads and air travel created new opportunities, and how they also created competition, which created even more opportunities. He taught his students that to achieve economic progress, innovation is key.

But he also gave warnings to his classes about the need to stay ahead of the competition: “Always remember that someone, somewhere, is making a product that will make your product obsolete.”

He was right. As Bill Gates acknowledged more recently, “Whether it’s Google or Apple or free software, we’ve got some fantastic competitors, and it keeps us on our toes.”

Doriot saw a big obstacle, however. While revolutionary ideas were probably brewing around the world every single day, most of these start-

TheHighIncomeFactor.com Special Report

up companies were unable to raise the necessary money to get off the ground. To make matters worse, money was tight after World War II, and the banks weren’t lending.

These groundbreaking ideas would never become realities. Instead, they’d remain trapped in the innovators’ minds. It was a serious setback to economic progress, and Doriot wanted to do something about it. As he’d profess to his students,

“A commercial bank lends only on the strength of the past. I want my money to do things that have never been done before.”

And so his idea was born.

What if, he wondered, you could pool money together from lots of investors and use that money to invest in many start-up companies? By holding an entire portfolio of start-ups, you could spread the risk. Rather than betting on the performance of a single company, you’d be betting on averages.

It would just take an occasional home run to more than offset the losses from many others. And those home runs could be knocked out of the park further than any other investment imaginable.

Why shouldn’t it work?

After all, oil companies succeeded by owning a portfolio of potential oil fields, and motion picture companies succeeded by holding a portfolio of movies. Their success didn’t depend on a single project being successful; their success depended on the winners being far bigger than the losers.

Doriot’s idea was a slight but powerful twist on the idea of venture capitalism, which had existed in various forms throughout history. Doriot was certainly not alone in terms of wanting to fund start-up companies in exchange for equity or ownership. During this enterprising time immediately following World War II, two other venture capital firms were created: J.H. Whitney &

Company and Rockefeller Brothers.

In fact, the term “venture capital” was coined by one of J.H. Whitney’s founders, when he described the company as a lender of private adventure capital; he later shortened it to venture capital.

But rather than pooling money together from many investors, like Doriot planned, more traditional venture capitalists would contact only wealthy moguls such as J.P. Morgan, the

Rockefellers, the Vanderbilts, or the Rothschilds to

Special Report finance an idea — or at least use their connections to find investors. For instance, in 1922, the

Vanderbilts helped start Pan Am. In 1938, Laurance

S. Rockefeller helped finance Eastern Airlines and

Douglas Aircraft.

Not just anyone was allowed to participate in these private equity deals. Only accredited investors were eligible; that is, individuals or households with over $1 million in assets, not counting their primary residence, greatly limiting those who’d qualify. For legal reasons, in most cases, venture capital projects could only accept a maximum of

500 accredited investors, narrowing the pool even further.

In other words, these private equity deals were only available to the politically connected wealthy elite.

The trend continues today. Bill Clinton, Al

Gore, Timothy Geithner, Colin Powell, Dianne

Feinstein, Newt Gingrich, and many other prominent figures have participated in private venture capital deals and made millions. There’s easy money to be made — provided you’re on the inside. It’s all for them and none for you.

And no wonder nobody wanted to share.

While the S&P 500 generates trivial returns of 7 percent to 10 percent per year, one study showed an average return among these private equity deals would have notched 30 percent per year, every year, for 20 straight years.

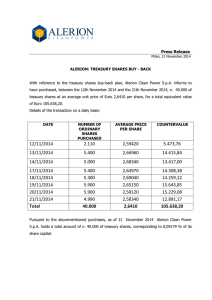

The following chart shows the results of a

$1,000 investment at 10 percent per year compared to 30 percent per year over 20 years:

200

180

160

140

120

100

80

30%

60

40

20

10%

0

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20

Years

At 10 percent, you’d increase your investment

Moneynews.com 3

to $6,727 — nearly sevenfold over 20 years. At 30 percent, it would increase by a factor of 190 to

$190,000. That means a modest $10,000 investment would turn into $1.9 million. Of course, these insiders were investing millions from the outset, so you can only imagine the wealth they generated.

The S&P 500 has never performed like that. In the past 50 years, the index has only cracked the 30 percent mark eight times. Private equity firms were a mind-boggling mystery to the masses

But Doriot knew about these “secret societies.”

As an astute businessman, he also knew the reason behind these impressive returns, and he was determined to find an efficient gateway to them.

Invest in Innovation

As we noted, Doriot believed that innovation was the key to economic success, but he also believed it was the key to investing success. When you invest in innovation, you’re at the ground level of development where more profit can be made. That’s because businesses at later stages of development must pay the profits to the earlier stages. The more stages in development, the less profit is available for those at the end.

The idea is simple: If the demand for airline travel increases, airplane prices may rise, but aluminum prices will rise faster. That’s because the extraction of the raw material used to build planes is at an earlier stage of production.

People may make money in the stock market on airlines, but it pales in comparison to the increase in aluminum prices, which in turn pales in comparison to the wealth created for the innovating founders. To make big money, you want to invest at the innovation level.

Now it should be clear why the Vanderbilts and

Rockefellers chose to invest in airlines and aircraft in the early 1900s; it was the industry leader of innovation at that time.

Doriot felt the problem with the traditional approach of investing directly into one company is that you’d either strike it rich or fail miserably. You were faced with extreme outcomes: either the road to riches or doorway to destruction. It was far too risky.

To counter that “all eggs in one basket” risk,

Doriot believed big money could be made by

4 taking calculated risks and nurturing numerous start-up companies over decades. Why not raise money from many investors — not just a single family or small group — and pool that money into a portfolio of innovative companies?

In other words, why not create a publicly traded company for venture capital? By allowing the public to invest, he could raise more money than any family or small group of investors could contribute, especially when considering all the soldiers returning from the war. It would be a major step toward fast economic progress after years of wartime stagnation.

Using his business skills, Doriot could select a portfolio of promising start-ups, provide expertise, management, and entrepreneurial skills in exchange for a big equity stake — 70 percent or more. Wall Street wondered why any company would accept the offer, while Doriot wondered why any company short on cash but big on ideas wouldn’t accept such a deal. If its idea were truly valuable, a small percentage of billions of dollars would still be a lot. It would certainly beat 100 percent of nothing.

It had never been done before. It was radical and fraught with risk. But it did have one thing going for it. It was an innovative idea. And if you’re going to invest, invest in innovation.

ARDC: The Birth of Venture Capital

Thus in 1946, Doriot put his bold idea into action and founded the American Research and

Development Corporation (ARDC), the world’s first publicly owned venture capital firm. Anyone could invest in ARDC and participate in venture capitalism.

Wall Street analysts heckled, booed, and hissed. American inventor and engineer Charles F.

Kettering — holder of 186 patents — publicly said

ARDC would go bust in five years.

Doriot shrugged it off. He sought funds from insurance companies, educational organizations, investment trusts, and any others, including individuals, who wanted to promote new businesses. After raising $3.5 million, ARDC took calculated gambles on high-risk ventures in exchange for an equity stake.

It brought the newest technology to the market,

TheHighIncomeFactor.com Special Report

from atom smashers to Zapata Off-Shore Company,

George H.W. Bush’s oil drilling company. It opened and expanded the frontiers of innovation. Former president of Lehman Brothers F. Warren Hellman said, “Doriot was at the forefront of fundamentally changing our economy.”

But Doriot’s real score came in 1957 when

ARDC gave $70,000 to a start-up company in exchange for a 70 percent equity stake. A tiny unknown company called Digital Equipment

Corporation (DEC), founded by two MIT engineers, planned to go head-to-head against

IBM’s mainframe computers.

Battling an 800-pound gorilla is not a good business model. And with only three employees,

DEC was inviting a big monkey on its back. It didn’t stand a chance.

At least, that’s how it appeared.

Just nine years later, DEC, with 7,000 employees, it launched its initial public offering

(IPO) at $22 per share — valued at $453 million.

When ARDC cashed out, this represented a return of over 500,000 percent on its investment.

Digital continued to grow to a peak of 140,000

“ behemoth Wall Street money machine had taken that opportunity away from individual investors.

ARDC was now in the hands of the wealthy elite, never to be heard from again.

But there is good news. ARDC may be gone, but the opportunity to apply Doriot’s philosophy has not. Today, entities called business development companies (BDCs) are doing similar things, but few investors know about them. They’re fairly new and one of the best-kept investment secrets for making a steady monthly income — and providing stellar returns.

They’re available to you today. I call them

Doriot Societies.

Discovering Doriot Societies

My name is Tom Hutchinson, and it’s my job with The High Income Factor to search for investment gems among the tens of thousands of opportunities and bring you the very best.

Fortunes have been made in private equity deals that were always unavailable to ordinary retail investors.

employees in 1987 and was acquired by Hewlett-Packard (NYSE: HPQ) in

2002. It was a true success story, showing that largescale venture capitalism was a legitimate way to create economic success.

Doriot’s initial idea for publicly traded venture capital firms was radical, but in the end he showed that not only could it be done, it should be done. It’s a necessary catalyst for capitalism and economic expansion.

But like any financial success story, it caught

Wall Street’s eye. In 1972, the conglomerate

Textron (NYSE: TXT) acquired ARDC for $66.16 per share — a 20 percent premium over its market price — valued at $400 million. Not bad for a company that began with $3.5 million of other people’s money.

The irony is that Doriot was a victim of his own philosophy: “Someone, somewhere, is making a product that will make your product obsolete.” The

”

I have spent my career as a financial adviser and Wall

Street professional searching for better ways to make clients money. I started as a clerk on the New York Mercantile

Exchange, but rapidly made my way up the corporate ladder as an adviser for large investment banks.

Once working on the inside, I realized the truth: Banks are more concerned with their bottom line than the clients’ bottom line.

I wanted to spend my time searching for better investment ideas, but management wanted me to spend more time hunting for new clients. That didn’t work for me. It’s a conflict of interest and unfair to the client. I resigned in 2005, and I have been an investor and financial editor ever since.

It has been my passion to search for and analyze the best opportunities, and the Doriot

Societies are one of my greatest discoveries yet.

During my research, I discovered that fortunes had been made in private equity deals that, throughout history, were always unavailable to ordinary retail investors. Just as a key can be used to unlock something, it can also be used to lock things tight. And that’s exactly what the wealthy

Special Report Moneynews.com 5

6 lawmakers did. They enacted laws to ensure you’d never get a chance to participate in these deals and enjoy the remarkable returns. They have remained a guarded secret — until fairly recently.

Now you can invest in start-up companies and get your share of this enormous venture capital industry, which accounts for 2 percent of GDP.

While that might not sound like much, that’s 2 percent of $17 trillion. Here’s how.

In 1980, Congress amended the Investment

Company Act of 1940 to create business development companies (BDCs), designed to raise cash to assist with the creation of small and medium-sized businesses — exactly what Doriot envisioned.

The idea was to give new public or private companies a better way to access cash to finance growth. Many of these companies couldn’t have sold bonds in the open market without offering unrealistically high interest rates. But with BDCs, that changed. These venture capital firms can now raise equity through initial public offerings (IPOs), pool the cash, and make investments.

Anyone can buy a BDC on the open market.

“

BDCs are selective when searching for business opportunities. They search for small to medium-sized companies, usually market caps of

$500 million or less, in exchange for managerial expertise and large equity stakes. The BDC may also make outright loans to these start-ups at relatively high interest rates, thus earning large interest payments each month.

In addition to helping with financing, the BDC offers managerial expertise to help companies get off the ground. In most cases, the BDC wants to exert significant control, which may mean putting managers in place, controlling voting shares, holding board seats, and other actions to propel the company to large-cap status ($10 billion or more).

Interestingly, even though BDCs have existed since 1980, the idea didn’t really catch on until

2000, when a lot of smart people started taking

BDCs can generate required to distribute

90 percent of taxable earnings each quarter.

But because they’re available to all investors, regulators made stringent requirements, and all

BDCs must follow regulations outlined by the

Securities and Exchange Commission. For instance,

BDCs have strict limits on the leverage they may use; that is, the ratio of borrowed funds to loaned funds. The total debt cannot exceed the total equity, or a 1:1 debt-equity ratio. Contrast this with banks that have leverage of 200:1 or more. No wonder so many banks have gone under.

BDCs must also be reasonably diversified and cannot hold more than 25 percent of assets in any capital investment (business that it controls), or businesses in the same industry. Most, however, hold dozens of investments. BDCs must also revalue their investments each quarter so there are no sudden surprises with devaluations, as with

Enron or with banks during the sub-prime lending meltdown. Investors are kept up to date with the fund’s value, which means less risk for you.

” notice of the potential benefits they provided. In 2000, only three existed, but today, there are over 30, with a total market capitalization of $27 billion.

They’re gaining popularity for a reason.

They’re modern versions of Doriot’s ARDC, offering high returns, stable income, and big opportunities for you. They allow you to invest in a professionally managed fund of start-up companies without the need to meet the high income and net worth restrictions imposed by private equity funds — or the need to be politically connected.

BDCs are similar to exchange-traded funds

(ETFs) such as QQQ (Nasdaq 100) or SPY (S&P

500) you’ve probably traded before.

Just like ETFs, most BDCs are listed on national stock exchanges such as the NYSE or Nasdaq.

However, it’s not a requirement, and some have declined listing. But you can buy or sell those that are listed just as you would shares of stock. By purchasing a BDC, you’re buying a piece of the venture capitalist’s portfolio.

A BDC raises capital through a one-time IPO and then uses that money to create a specialized portfolio of start-ups, which is managed by an

TheHighIncomeFactor.com Special Report

investment adviser. From that point forward, the shares trade in the open market, just like any stock.

It is this open-market arrangement that allows

BDCs to attract more capital than venture capital firms, which helps a greater number of innovative companies get off the ground.

There’s another benefit. BDCs are closed-end funds, which means they have a limited number of shares they can issue. They are not subject to sudden redemptions (investors selling shares in order to get their money back) as is common with ordinary mutual funds.

Instead, all money raised during the IPO stays with the fund, so the investments are more stable.

Rather than the BDC’s value fluctuating because of surprise redemptions, it fluctuates according to the performance of its portfolio.

By trading in the open market, you don’t need to wait for fund managers to sell their investments before they can distribute profits to investors.

Instead, you can just sell your shares to another investor. It’s easy to cash out of your investment since BDCs are very liquid, which means the bidask spreads are low, and commissions are the same as for shares of stock.

Best of all, BDCs can generate stable income because they are usually registered investment companies (RICs). RICs are required to distribute at least 90 percent of taxable earnings each quarter.

Most pay more, usually 98 percent of taxable income and 100 percent of short-term capital gains.

A big advantage of RIC status is that no income tax is paid at the corporate level; all profits pass through to the investors. Less for Uncle Sam means more profits in your pocket.

Dividends are also paid at a stable level since most of the fund’s assets are debt securities of the start-up companies. This also makes them great substitutes for fixed income, especially for investors seeking higher yields in today’s nearly zero-interest environment.

Currently, BDC yields range from 10 percent to 25 percent, which easily beats the 0.1 percent rates currently offered by Treasury bills. A $10,000 investment in a BDC earns $1,000 to $2,500 per year. Compare that to the 10 bucks you’ll get with

T-bills.

BDCs are a great way to capitalize on higher-

Special Report yield income by a simple purchase of a publicly traded company. For just a few dollars, you can now invest directly in innovation. There has never been an easier way, and it’s all because of Doriot.

The ABCs of BDCs

BDCs make money in four basic ways: (1) takeover and repair; (2) buy and flip; (3) becoming the bank.; (3) via Ownership Equity Financing; and (4) becoming the bank.

For “takeover and repair,” BDCs search for distressed innovative companies, usually in the technology, energy, healthcare, financial, or manufacturing sectors, and take over the firm.

The BDC provides managerial expertise, whether by using talent from within the BDC, or by hiring another firm. The BDC usually charges consulting fees plus performance incentives, which also helps to increase the fund’s value — and your profits.

By providing managerial expertise, the investment adviser expects to increase the company’s value and sell it at a profit.

In 1993, one society took over Continental

Airlines for $66 million. New management was brought in with a focus on efficiency and lucrative routes. Within five years, it was sold for over $700 million, a return of over 960 percent.

During the Asian financial crisis, another society took over the Long-Term Credit Bank of

Japan for $1.1 billion. In just a few years, this $1.1 billion investment was worth $7 billion — a gain of 536 percent. Just imagine how a small fraction of these returns would boost your portfolio.

The “buy and flip” strategy is similar, but without taking control of the company. Remember, one of the main skills of a BDC’s management is to search for and evaluate companies. It may find a company that’s undervalued rather than one searching for financing or management guidance.

Instead, it’s just a good find.

Many times, these are “orphaned” companies, which have been spun off from the parent company and deserted. The BDC may like the way management is running the business and the outlook for the company. Rather than taking it over, it’ll operate on the Yogi Berra principle, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Moneynews.com 7

8

Instead, it’ll just buy the shares and hold them in the BDC’s portfolio, hoping to cash in when the rest of the market figures out the true value.

This is more like the Warren Buffett or Peter Lynch approach to investing. Buy companies you know and understand when prices are low, and let time take care of the value.

The advantage to you is that the BDC acts like your personal team of financial analysts. They’re some of the brightest minds on Wall Street.

They’re not just reading financial reports; they’re speaking with management and conducting full business valuation analyses. They’re more likely to uncover gems than the average investor.

One BDC bought Digital

Insight Corporation from

Intuit in September 2013 for

$1.065 billion. Just 124 days

“ later, it was sold to NCR Corp for $1.65 billion — a four-month profit of $600 million.

Another bought Norcast Wear Solutions for

$190 million then flipped it seven hours later for

$209 million — a gain of $19 million, or $2.37 million per hour. Will you ever find those kinds of returns in the stock market? Never. But they’re quite common in Doriot Societies. That’s what happens when you invest in innovation.

The third way BDCs profit is by using a special type of equity I call “OEF shares.” OEF shares are not available on the stock market. To be clear, these are not risky pink sheets, boring loans, dangerous commodities or options. They’re a special type of equity accessible to these Doriot Societies that allows them to snap up gains that make 10-baggers look conservative.

Georges Doriot is one of the earlier, major success stories of using OEF shares. In 1956, he bought $70,000 worth of OEF shares belonging to a company called Digital Equipment Corporation.

Digital would become famous for inventing the minicomputer — which ended IBM’s dominance as the primary manufacturer of mainframe computers.

Within a few years, Doriot’s OEF shares were valued at more than $400 million. That’s a gain of 70,000 percent, or enough to turn every $1,000 into $700,000. Think for a moment about the last time you ever heard about a regular stock soaring

70,000 percent. That’s a genuine once in a lifetime event on the NYSE — but it’s far from unheard of in these societies.

Here are some famous examples you might recognize:

• One society made an investment of $12.5 million in Google’s OEF shares. That $12.5 million eventually exploded to more than $4 billion — meaning this society enjoyed

Scouring the sector, I came up with six Doriot

Societies primed for making big returns and outpacing the market.

” a return of more than 32,000 percent. Regular investors who bought Google from day one have had, at best, a chance at a gain of around 1,000 percent.

• Another society bought

$12.2 million worth of Facebook’s OEF shares.

Their stake exploded to a value of $5.8 billion — delivering them a return of 47,000 percent. Regular investors who bought Facebook from day one, have at best around a 100 percent gain.

• Still another society purchased $6.7 million worth of eBay’s OEF shares and within two years, that $6.7 million turned into $5 billion. A return of nearly 75,000 percent. If you as an individual investor had purchased eBay immediately, beginning at the IPO, and held it until its 2004 peak, you’d still only have grabbed — at most — a gain of 3,012 percent.

Society members are banking gains like this all the time, although not all of them are

10,000 percent gains and beyond. Still, though, even without those astronomical returns, many investments have been impressive. One society recently enjoyed a 2,000 percent burst through buying OEF shares of Oculus VR. Another snapped up a return of 5,000 percent on WhatsApp through these OEF shares. And another is expected to ultimately enjoy a return of about 8,650 percent on its investment in OEF shares of King Digital.

No matter how you slice it, getting gains like this with any consistency out of the market is next

TheHighIncomeFactor.com Special Report

to impossible. It’s not something we can expect as individual investors . . . but what we can do is try and capture a piece by putting our money to work in well-run BDCs.

The fourth way BDCs make money is to act like the bank — of course, with much higher rates of return; some charge in the 12 percent to 25 percent range. And remember, at least 90 percent of that must be distributed to shareholders: That’s you.

The BDC makes short-term unsecured loans to distressed companies, earning the difference, or spread, on what that money cost them, much like a bank.

It may sound like high risk, but the BDCs have a backup plan — they can actually take over the company if it defaults. So, high returns with minimal risk — who can say no?

If you invest now, it gets even better. Because of the nearly-zero interest rate environment we’ve been in for years, BDCs have been able to secure long-term capital at very low fixed rates.

The loans, however, are made at variable rates, which reset several times per year. This means the borrowers pay more as rates rise, which produces immediate income for the BDC — and you.

If you were, instead, invested in bonds, your investment value would fall as rates rise.

So BDCs offer significant protection against the risk of rising interest rates, a real concern since interest rates are expected to rise as the Fed tapers its bond-buying stimulus programs. If you’re looking for steady fixed income, Treasury bills are not the place to be.

Invest in innovation instead. And because of

General Doriot, this option is no longer hidden.

You just need to know where to look.

Uncovering the Six Elite Doriot Societies

While BDCs offer unique advantages to investors, not all are created equal. Each has its own business model, and each requires careful analysis.

That’s where I come in.

In my role as a financial editor, I have studied all of the Doriot Societies from top to bottom, left and right, inside and out. I’ve narrowed the list and only included those that are exchange traded.

Investing in non-listed companies exposes you to an unnecessary risk since there may be no practical

Special Report secondary market should you need to sell. I’m not going to gamble with your money.

Scouring the sector, I came up with six Doriot

Societies primed for making big returns and outpacing the overall market. Because each is publicly traded, it will have a ticker symbol just like shares of stock. Just type the ticker into your broker’s platform and that’s how easy it is to become part of a Doriot Society today.

Doriot Society No. 1: The Ares Society

(Nasdaq: ARCC)

The “Ares Society” is located on Park Avenue,

New York. It is Ares Corporation, which carries the ticker ARCC. With $74 billion under management,

Ares specializes in acquisitions, leveraged buyouts, and rescue financing.

This company has returned impressive numbers since the market crash in 2009. A $48,000 investment would be $316,800 today — that’s a

560 percent increase, or over 45 percent per year for the past five years.

Since inception, Ares has consistently outperformed the S&P 500 by delivering 14 percent returns per year. Considering that 80 percent or more of all money managers don’t beat the index in any year, Ares has consistently beaten the odds.

But that’s not all. At its current price around

$17 as we were going to press with this special report, it’s yielding nearly 9 percent with its quarterly dividend. It’s a great hedge for your portfolio if the overall market pulls back or trades sideways.

$0.6

$0.5

$0.4

$0.3

$0.2

$0.1

ARCC Dividends

$0.0

3/05 9/06 3/08 9/09 3/11 9/12 3/14

Moneynews.com 9

Doriot Society No. 2: The Hamilton Society

(NYSE: HTGC)

Located on Hamilton Avenue in Palo Alto,

California, this Doriot Society is Hercules

Technology Growth Capital Inc. and trades under the ticker HTGC.

Founded in 2003, HTGC makes relatively small investments between $1 million and $30 million, so it can make loans to many companies.

It has invested over $4.2 billion in more than

270 companies, mostly in the technology and life science industries.

That’s a lot of investments. Remember, all it takes is one home run to make the entire venture worthwhile.

HTGC racked up a 30 percent return at the end of 2013, but has dropped in 2014 with the tech pullback. It’s currently trading around $15 per share as we go to press, but that low price is giving it an enticing 8.4 percent yield on its quarterly dividend.

$0.4

$0.3

$0.2

$0.1

$0.0

HTGC Dividends

4/06 11/07 5/09 8/10 3/12 8/13 offering of 12 million shares in February 2014. It’s a sign the company is raising more cash to take advantage of the many opportunities it’s finding.

AINV Dividends

$0.6

$0.5

$0.4

$0.3

$0.2

$0.1

$0.0

12/04 6/06 3/08 9/09 3/11 9/12 3/14

Doriot Society No. 3: The 57th Street

Society (Nasdaq: AINV)

Located on West 57th Street in New York, this

Doriot Society, Apollo Investment Corporation, is finding great opportunities.

While it usually keeps each investment below

$250 million, it has invested $8.6 billion since inception in 2004, with $2.8 billion last year, and

$986 million last quarter, the highest level of quarterly activity in its history.

It’s trading just above $8 as we go to press, providing investors with an eye-catching 9.60 percent yield. That’s down from its 52-week high of

$9.21, but the change is mostly due to a secondary

10 TheHighIncomeFactor.com

Doriot Society No. 4: The Society of Oak

Boulevard (NYSE: MAIN)

The “Society of Oak Boulevard” refers to the Main Street Capital Corporation, which is headquartered at 1300 Post Oak Boulevard in

Houston, Texas.

It trades under the ticker symbol MAIN.

Although publicly traded, it generally remains low key and out of the financial media spotlight.

It operates out of an ordinary office amongst hundreds of others, but the performance is anything but ordinary.

Many societies buy shares or lend money, but this company does both.

It generates equity when start-up values rise, and receives big interest payments in the meantime

— as of this writing, MAIN pays a 6.6 percent dividend to shareholders every month.

Its track record has been impressive, and the price has more than doubled in the past five years.

That’s over 15 percent per year. The returns are high, and the costs are low, just 1.7 percent of total assets.

This society is swimming in cash and the payouts are growing rapidly. Management has increased payouts by an average of 8.5 percent each year since inception.

In 2013, this society made two extra payments, for a total of 14 checks for you — not counting any capital gains from the shares. It’s around $30 a share as we go to press, which is a great entry point in my opinion.

Special Report

$0.4

$0.3

$0.2

$0.1

$0.0

MAIN Dividends

8/08 8/09 8/10 8/11 8/12 7/13 5/14

Doriot Society No. 5: The Prospect Capital

Society (Nasdaq: PSEC)

Prospect Management Corporation is headquartered on East 40th Street in New York and trades under the ticker PSEC. It recently closed below $10 for the first time since December 2011, mostly due to an earnings miss, and it now trades significantly below its $10.68 book value. The dividend yield as we go to press is 13 percent.

The last earnings report showed net income of $247 million, up 30 percent. The company is confident in these results and declared monthly dividend payments through December

2014. Companies only make such long-term announcements when their cash flows are rock solid, steady, and low risk. PSEC’s dividends have increased every month for 54 straight months. Not only does it deliver high returns, it delivers extra cash to you every single month. on this list. “The 555 Society” is KKR Financial

Holdings, located at 555 California Street, San

Francisco. It trades under the ticker symbol KKR, and while it’s not considered a BDC, it is a powerful firm in the realm of private equity and leveraged buyouts.

KKR Financial Holdings is actually the famed investment firm of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, which boasts the first leveraged buyout over $1 billion as part of its storied history. Yes, these were the people behind the $25 billion purchase of RJR Nabisco in 1989, which inspired the best-selling book and

HBO movie Barbarians at the Gate. That deal was the largest leveraged buyout in history; that is, until the firm’s 2007 leveraged buyout of the Texas utility company TXU Corporation for $45 billion.

KKR aims for big buyouts and big profits. For the first quarter of 2014, revenues increased 100 percent to $303 million. Those are the returns investors expect with Doriot Societies. But the striking performance isn’t just recent. KKR has returned 3,300 percent since the market bottom in

2009. Since then, a $48,000 investment would have turned into $1.6 million in just five years. Had you left it up to the market, that same investment would be just $112,000. That’s the power of investing in innovation.

With nearly $55 billion in assets, KKR is poised for continued performance. In the meantime, it pays a quarterly dividend with an annual yield of 7.7 percent to provide steady cash to your portfolio.

KKR Dividends

$0.5

$0.4

$0.3

PSEC Dividends $0.7

$0.6

$0.5

$0.4

$0.3

$0.2

$0.1

$0.2

$0.1

$0.0

8/10 3/11 8/11 2/12 8/12 2/13 8/13 2/14

$0.0

6/05 6/08 10/10 10/11 11/12 11/13

Doriot Society No. 6: The 555 Society

(NYSE: KKR)

This last Doriot Society isn’t quite like the others

Covered Calls: Your Five-Minute

‘Retirement Miracle’

If you own dividend-paying companies, you know you’re getting a stream of income. But you

Special Report Moneynews.com 11

don’t simply have to rely on the companies to pay you — with a little extra work on the trading front, you can stockpile extra monthly checks. Better yet, it’s a relatively conservative strategy, and can be applied to your Doriot Society investments to boost your overall gains.

With the covered call strategy, you sell one call for every 100 shares owned. If you own 100 shares of stock, you sell one call. If you own 500 shares, you can sell five calls.

By selling calls, you receive cash up front. It’s cash you can use immediately for any reason. It’s your compensation for accepting the potential obligation to sell your shares for the strike price.

You can go shopping, buy more shares, or use it to buy put options to protect your portfolio.

Selling calls doesn’t guarantee that you’ll sell your shares. The shares will only be sold if the call buyer exercises, which should happen only if the stock’s price is greater than the strike price at expiration (the option expires in the money) or if a dividend is paid near expiration.

Why must you own the shares? If you sold a call without owning shares, you’re liable to deliver shares for the strike price. Because there’s no limit on how high a stock’s price can rise, you’d have unlimited risk as the stock price rises above the strike. With a covered call, you own the shares, so that upside risk is “covered.”

However, that doesn’t mean the strategy is without risk. Because you’re holding the shares, you have downside risk. The stock’s price will always be far greater than the option premium received — and you own those shares — so you

Automate Your Way to Bigger Profits

You may not have time to watch the stock markets everyday to make trades. But that’s okay — you don’t have to sit on the sidelines and let the potential for gains pass you by.

In fact, there’s a type of investment built just for you: the dividend reinvestment plan, or DRIP for short.

You’ve probably heard of DRIPs before, but some things have changed. It’s easier than ever to get into one, and if you own a brokerage account, you probably have access to

DRIP-like features without knowing it.

First, why a DRIP? Companies offer them directly to investors, usually through a third-party shareholder service provider. Simply enough, you buy a small number of initial shares and the company uses the dividends it pays quarterly to buy you more, automatically, for as long as you like.

They charge little or nothing, and you get a bunch of benefits. Among them are the following:

Compounding at work: The incoming dividends create a flow of interest that grows upon itself, incessantly. Rather than sitting as cash in a bank account earning next to nothing, the dividend interest immediately purchases shares, even fractions of shares, without you moving a muscle. This is why creating a DRIP for a longterm investing horizon can lead to powerful growth. Time is money when it comes to compounding.

Avoid bad trading decisions:

The great thing about DRIPs is that you can and likely will forget you own them. This greatly reduces the chances that you let emotions take over. Early on, the “drip” effect won’t seem like much. If the stock appreciates, you might consider selling it. (Most plans charge a small fee to liquidate.) But you shouldn’t, if the long term is your view.

Develop consistency: Financial advisers often tell clients to buy stocks at set periods to avoid chasing returns.

Known as “dollar cost averaging,” the point is to let the money flow regardless of the current price. Over time, you’ll buy more shares when the stock is cheaper, something you may not do on your own.

Pay less: Even the lowest-cost broker will charge you a few bucks for a typical stock trade. DRIP transactions, meanwhile, often cost nothing. That’s hard to beat, and more money left in the account, compounding over time for you.

Keep in mind, you will receive

Internal Revenue Service forms from your brokerage or transfer agent showing your dividend income, even if you reinvest every penny.

This might not be a huge problem, unless you fail to keep track of your

DRIP taxes over a long period. Talk with your tax preparer in advance or consider DRIP-tracking software. Or try to invest inside a tax-advantaged individual retirement account.

To find DRIPs, check the Internet or go to the site of the companies you’re interested in to see if they offer one.

For instance, if you decide on

Hercules Technology Growth Capital

(HTGC) from this special report, you would search the Internet for

“HTGC DRIP,” which should lead you to the page on the Hercules website that addresses its DRIP program, http://investor.htgc.com/ dividendsReinvestmentPlan.cfm.

12 TheHighIncomeFactor.com Special Report

don’t want the price to fall.

If you’re ever going to use a covered call strategy, Rule No. 1 is to be sure it’s a stock you’re comfortable holding.

New traders wonder why anyone would sell options. Who wants an obligation?

First, option sellers receive cash up front. Cash in the pocket counts. Second, obligations aren’t necessarily bad. Investors willing to sell shares aren’t facing an adverse obligation.

Instead, they’re receiving cash for something they were going to do anyway. And chances are, if you bought shares, you have the intention of selling them at some time. The difference is that outright stockowners don’t get paid to sell their shares. Covered call writers do.

Let’s see how you can benefit as a covered call writer. Say you own 100 shares of Company

Z, trading for $55 at the end of

December. The January $55 call was $2.

If you sell one January $55 call for $2, your stock’s cost basis

“ you hadn’t sold the call, you’d be down $2, or 3.6 percent. The stock fell $2 but you made $2 from the call, so you’re even. The option helped turn a loss into a flat return.

If the stock price remained at exactly $55 at expiration, the $55 call expires worthless. With a cost basis of $53, you could sell your shares for the current $55 price, which is a $2 unrealized gain on a $53 cost, or 3.8 percent. It may not sound like much, but that’s for one month. If you continually sold monthly calls and the stock price stayed still, you’d have a compounded gain of 56 percent while stock investors would be flat, assuming that options premiums remained about the same month to month.

By using options, multiplying profits is easy,

By selling calls, front. It’s cash you can use immediately for any reason.

is reduced by that premium. If you just purchased shares for $55, your effective cost is $53. It’s as if you paid $55 for the shares, but received a $2 cash rebate, which reduced your purchase price — and reduced your risk.

That’s if you bought right away. If you purchased the shares months or years earlier, say for $20, your cost basis is $18. Regardless of the price paid for the shares, it’s the current price that determines whether you’ll make money.

Let’s fast forward to January expiration and see what happens. At expiration, the stock’s price will either be below $55, exactly $55, or above.

If the price is $55 or below, the call expires worthless. You keep the $2 premium, and you can write another call. Each time you sell a call against your shares, your cost basis is further reduced.

Many covered call writers have written their shares into a negative cost basis, which means they received their principal back plus a guaranteed profit — and still own the shares.

By selling the call, you have some downside protection. If Company Z falls to $53 at expiration, you break even since your cost basis is also $53. If

” even if stock prices don’t move. Covered call writers can perform remarkably well in sideways markets. If the stock’s price is above $55, you’ll get assigned (the call buyer exercises) and sell your shares for the $55 strike. The most money any covered call writer will ever receive is the strike price. Whether the stock price is $55.01 or higher at expiration, you’ll receive $55, which, again, is a 3.8 percent return in one month.

But that’s a return you could easily calculate before entering the trade, which takes a lot of uncertainty out of simply owning shares. Yes, you’ll miss out on additional upside gains if shares had surged to, say, $70, but that’s the price you pay for the certainty of your upside return.

If your shares get “called away” you’ll have to buy more shares if you want to write another covered call the following month for the same stock. Alternatively, since you’ll have cash to invest, it’s an opportunity to buy a different stock or do whatever you wish in the market.

The option’s time value is the reason the covered call writer can make money when the stock price doesn’t move, or even falls slightly.

Writing calls against stocks is yet another reason why option traders can multiply profits.

New option traders believe the risk of the covered call is getting their shares called away.

Special Report Moneynews.com 13

After all, who’d want to sell shares for $55 if they’re worth more in the open market? Covered call writers must realize getting called away still means making a profit — just not as much. Missing out on some reward is not a risk but a missed opportunity. The risk of the covered call is having the stock’s price fall below your breakeven point.

Again, that’s why covered call writers must be comfortable holding the shares of stock.

So what are the benefits?

Outright stock investors need the stock price to rise to make money. Covered call writers can afford to have the stock price rise, fall a small amount, or stay flat — and still make money. Option traders have more ways to make money. Profits are more consistent with fewer portfolio fluctuations.

Does this mean covered call writers are expected to make more money? In the long run, no. That’s because they sell off all rights to shares above the strike price. Over time, covered call writers will miss out on the occasional home runs that are bound to occur. The covered call writer benefits by smaller, but consistent profits — the equivalent of scoring base hits, not home runs.

As a covered call writer, you’re not required to just sit and wait for expiration. Instead, you can buy back (close) the short call at any time for any reason. If Company Z’s price stays the same or falls, the $50 call’s value begins to fall. With less time remaining, or because of a lower stock price, it’s not worth as much. If the call’s price falls from $2 to $1 prior to expiration, you can buy it back to get out of the contract.

Each time you pay to close out a short call, you’ll increase your cost basis by the purchase price. If you sold for $2 and bought it back for $1, you profited by only $1 but also have no chance of having your shares called away. It’s as if you never entered the covered call but have now reduced your cost basis by one dollar from $55 to $54.

The covered call is one of the most versatile of option strategies and there are countless variations.

You can sell in-the-money calls for more downside protection, and you could sell out-of-the-money calls for greater profits. Each strike represents a different risk-reward profile.

Regardless of your choice of strikes, the covered call strategy provides an opportunity to multiply profits — and reduce risk — that is just not possible for stock buyers.

Your Monthly Payout Schedule

It’s the regularly-paying Doriot Societies like the ones I’ve chosen for you that make excellent candidates for those of us who need to generate monthly income over the long term. Below, I’ve included a schedule of the last year’s worth of payments for t h e six

Doriot Societies I’ve highlighted in this report:

Societies

Society of Oak Boulevard

Jan.

2,16

Feb.

19

Mar.

19

Apr.

17

May

17

June

18

Jul.

18,31

Aug.

19

Sept.

18

Oct.

17

Nov.

19

Dec.

17,26

Total

15

The Ares Society — — 19 — — 18 — — 18 — — 17 4

Prospect Capital Society

Payments

— — 7 — 10 — — 9 — — 14 — 4

3 2 6 2 4 4 3 4 4 2 4 5 43

This payment schedule is based on a $10,000 investment made into each Doriot Society in June of 2009 (a total initial investment of

$60,000). If you were to invest $60,000 now, your payouts would be much lower since the annual increases have not kicked in yet. This shows you the importance of investing into these Doriot Societies as soon as possible. You can of course start with as much money as you feel comfortable with.

Societies

Society of Oak Boulevard

Jan.

$302

Feb.

$151

Mar.

$151

Apr.

$151

May

$151

June

$151

Jul.

$302

Aug.

$151

Sept.

$151

Oct.

$151

Nov.

$151

Dec.

$302

Total

$2,263

Yield

23%

The — — $942 — $3,768

57th Street Society

The Ares Society

Hamilton Society

Prospect Capital Society

Monthly Payment

$245

—

—

—

$546

$245

—

—

—

$396

$245

$553

$347

$333

$245

—

—

—

$2,570 $396

$245

—

—

$333

$245

$553

$347

—

$1,670 $1,295

$245

—

—

—

$546

$245

—

—

$333

$245

$553

$347

—

$1,670 $1,295

$245

—

—

—

$245

—

—

$333

$245

$553

$347

—

$2,936

$2,211

$1,387

$1,332

29%

22%

14%

13%

$396 $1,670 $1,446 $13,897 23.16%

14 TheHighIncomeFactor.com Special Report

The

High Income Factor

The High Income Factor is a monthly publication of Newsmax Media, Inc., and Newsmax.com. It is published at a charge of $ 109 for print delivery

($ 97.95

for digital/online version) per year through

Newsmax.com and Moneynews.com.

The owner, publisher, and editor are not responsible for errors and omissions. Rights to reproduction and distribution of this newsletter are reserved.

Any unauthorized reproduction or distribution of information contained herein, including storage in retrieval systems or posting on the Internet, is expressly forbidden without the consent of Newsmax

Media, Inc.

For rights and permissions, contact the publisher at

P.O. Box 20989, West Palm Beach, Florida 33416 .

To contact The High Income Factor, to change email, subscription terms, or any other customer service related issue, email: customerservice@newsmax.com, or call us at (888) 766-7542 .

© 2014 Newsmax Media, Inc. All rights reserved.

Newsmax and Moneynews are registered trademarks of Newsmax Media, Inc. The High Income Factor is a trademark of Newsmax Media, Inc.

Financial Publisher

AARON DEHOOG

Editorial Director/Financial Newsletters

JEFF YASTINE

Senior Financial Editor

TOM HUTCHINSON

Art/Production Director

PHIL ARON

Closing Thoughts

Investors have never been able to match the returns of Wall

Street professionals. It’s no wonder. All the great investments have been guarded, whether by political influences or corporations snapping up the opportunities. Georges Doriot changed that.

Because of him, anyone can invest in innovation by purchasing a publicly traded venture capital fund — a Doriot Society. He pioneered a way for all investors to participate in and profit from venture capital. And in doing so, he changed the economy, the way we invest, and the way we make money.

Doriot died in 1987 at age 87. His estate held more than 31,000 shares of Digital Equipment valued at over $53 million. But it wasn’t his idea that made him this money. It was his actions.

As he used to profess to his entrepreneurs at Harvard, “Without actions, the world would still be an idea.”

Uncovering the Doriot Societies means nothing unless you take action. Being a Wall Street insider and analyst, I’ve uncovered the best of the best for you. Allocate part of your portfolio to one or more of these Doriot Societies. All it takes is one home run to make that action more valuable than the idea.

As a member of any of these Doriot Societies, you’ll be part of the financial elite — not because of your wealth or connections, but because you are one of the few who acted to turn investment innovation into investment gold.

Sincerely,

DISCLAIMER: This publication is intended solely for informational purposes and as a source of data and other information for you to evaluate in making investment decisions. We suggest that you consult with your financial adviser or other financial professional before making any investment. The information in this publication is not to be construed, under any circumstances, by implication or otherwise, as an offer to sell or a solicitation to buy, sell, or trade in any commodities, securities, or other financial instruments discussed. Information is obtained from public sources believed to be reliable, but is in no way guaranteed. No guarantee of any kind is implied or possible where projections of future conditions are attempted. In no event should the content of this letter be construed as an express or implied promise, guarantee or implication by or from The High Income Factor, or any of its officers, directors, employees, affiliates, or other agents that you will profit or that losses can or will be limited in any manner whatsoever. Some recommended trades may (and probably will) involve commodities, securities, or other instruments held by our officers, affiliates, editors, writers, or employees, and investment decisions by such persons may be inconsistent with or even contradictory to the discussion or recommendation in The High Income Factor. Past results are no indication of future performance. All investments are subject to risk, including the possibility of the complete loss of any money invested.

You should consider such risks prior to making any investment decisions. See our Disclaimer, as well as a list of stocks that the Senior Financial Editor owns by going to highincomefactor.com.

Special Report

Tom Hutchinson

About Tom Hutchinson

I’ve worked in finance my entire career, from the back office of a

Wall Street firm to the floor of the New York Mercantile Exchange learning how markets work. Eventually, I became a financial adviser where I met with thousands of investors and managed the portfolios of hundreds over the course of about 15 years. I left my career as a financial adviser, writing for The Motley Fool as well as StreetAuthority LLC, researching companies, industries, and markets. In The High Income Factor, I can bring you the full benefit of my years of investing experience.

Moneynews.com 15