Excessive Reasonableness

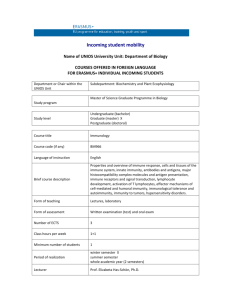

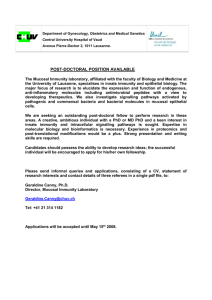

advertisement