OF

DEMOCRATS

&

DICTATORS

The De velopment of Law

From Elizabethan England t o the Modern Age

Teacher’s Guide

OF DEMOCRATS & DICTATORS

The Development of Law

Teacher’s Guide

Developed by

Marshall Croddy

Bill Hayes

Writer

Bill Hayes

Editor

Bill Hayes

Production & Design

Andrew Costly

CRF Board Reviewer

Peggy Saferstein

Todd Clark, Executive Director

Marshall Croddy, Director of Programs

Constitutional Rights Foundation, 601 South Kingsley Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90005

(213) 487-5590, crf@crf-usa.org, www.crf-usa.org

Standards reprinted with permission:

National Standards copyright 2000 McREL, Mid-continent Research for Education and Learning, 2550 S. Parker Road,

Suite 500, Aurora, CO 80014, Telephone 303.337.0990.

California Standards copyrighted by the California Department of Education, P.O. Box 271, Sacramento, CA 95812.

Cover photographs:

Reprinted with the permission of iStockphoto.com: cover #7 (Jeremy Edwards), cover #6 (Vazhappully Bahastcaran

Baiju).

Public domain photographs from:

Wikimedia Commons: cover #1, #4, #5

Wikipedia: cover #2

ISBN: 978-1-886253-40-7

Copyright 2007 Constitutional Rights Foundation. All rights reserved.

OF DEMOCRATS & DICTATORS

The Development of Law

Table of Contents

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4

Unit 4: The Dreyfus Affair . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .64

Law-Related Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4

The Arrest and Court-Martial . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .66

Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

The Unraveling of the Case . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .70

Classroom Strategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Handling Controversy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Unit 5: The Totalitarians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .76

Directed Discussions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Small-Group Activities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Hitler’s Nazi Germany and

Stalin’s Soviet Union . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .79

Brainstorming . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

The Stalin Purges . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .81

Simulations and Role-Playing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Hitler’s Rise to Total Power . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .86

Resource Experts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

Nazi “Justice” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .89

The Plot to Assassinate Hitler . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .92

Unit 1: Sir Edward Coke and the

Common Law . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10

Unit 6: War Crimes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .96

The Rise of the Common Law . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

The Hague Conventions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .98

The Trial of Sir Walter Raleigh . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17

The Nuremberg Tribunal . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .100

Coke on the Bench . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

The International Criminal Court . . . . . . . . . . .103

The Case of the Five Knights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .26

Later Developments in Common Law . . . . . . . . .31

Unit 7: Gandhi and Civil Disobedience . . . . .106

India and Gandhi . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .108

Unit 2: The Enlightenment Philosophers . . . . .36

Gandhi Against the Empire . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .111

The Enlightenment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .39

Montesquieu and Rousseau . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .43

Unit 8: International Law . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .114

International Law . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .116

Unit 3: The Code Napoleon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .48

Law of the Seas . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .119

The French Revolution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .50

A Treaty to Control the Spread

of Nuclear Weapons . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .122

Making the Code . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .53

The Civil Code . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .58

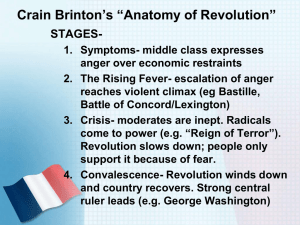

Unit 3

The Code Napoleon

Unit Overview

This unit is designed to supplement instruction on the French Revolution and Napoleon. It consists of

three lessons:

Lesson 8: The French Revolution introduces students to the revolution and Napoleon. Students read

about and discuss the French Revolution. Then in small groups, students create an updated Declaration

of the Rights of Man. Finally, students read about and discuss Napoleon.

Lesson 9: Making the Code explains what the law in France was like before the Civil Code and how the

code was made. First, students read about and discuss the law in France before the Civil Code. Then they

read about and discuss how the code was made. Finally, in small groups, students examine proposed rational

reforms and decide whether such reforms would stand a chance of being enacted in today’s world.

Lesson 10: The Civil Code examines the contents of the code, its legacy, and the differences between the

Civil Code and common law. On day one, students read about and discuss the contents of the Civil Code.

Then in small groups, students apply the law of torts found in the Civil Code to hypothetical cases. On day

two, students read about and discuss the legacy of the Civil Code. Then they read about and discuss the differences between the Civil Code and common law. Finally, in small groups, students role play advisors to an

emerging democracy and advise whether or not the country should adopt the jury system.

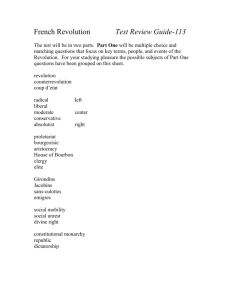

Standards Addressed

National High School World History Standard 32: Understands the causes and consequences of

political revolutions in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. (4) Understands the political beliefs

and writings that emerged during the French Revolution (e.g., characteristics and actions of radical, liberal, moderate, conservative, and reactionary thinking; the ideas in the “Declaration of the Rights of

Man and the Citizen” . . . ; the implications of the “Code Napoleon” for Protestant and Catholic

Clergy, property owners, workers, and women).

National High School Civics Standard 23: Understands the impact of significant political and

nonpolitical developments on the United States and other nations. (2) Understands the effects that

significant world political developments have on the United States (e.g., the French, Russian, and

Chinese Revolutions . . . ).

California History-Social Science Content Standard 10.2: Students compare and contrast the

Glorious Revolution of England, the American Revolution, and the French Revolution and their

enduring effects worldwide on the political expectations for self-government and individual liberty. (2) List the principles of the Magna Carta, the English Bill of Rights (1689), the American

Declaration of Independence (1776), the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen

(1789), and the U.S. Bill of Rights (1791). (4) Explain how the ideology of the French Revolution led

France to develop from constitutional monarchy to democratic despotism to the Napoleonic empire.

Of Democrats & Dictators

48

Vocabulary

canon law (KAN bn LO) n. The law of the Catholic

Church.

common law (KOM bn LO) n. 1. The judge-made law

in England that evolved over centuries. 2. Judgemade law as opposed to statutory law.

Consulate (KON sb lbt) n. The name of the first government formed by Napoleon after he seized power in

1799. Napoleon was the first consul.

Estates General (i STAb5TZ JEN b rbl) n. The French

national legislature before the revolution. It consisted of three groups, called “estates”—the clergy, the

nobility; and the rest of the people of France.

feudalism (FEW dbl iz bm) n. The political and economic system used in Europe between A.D. 800 and

1400. It was a class system based on landholding

and the obligations of the tenant to the lord.

guillotine (GEb5 yb teb5n) n. A device for beheading a

person. It consists of a heavy blade that falls along

tracks. It was invented during the French

Revolution by the French doctor Joseph Ignace

Guillotin.

inquisitorial system (in KWIZ b tor eb5 bl SIS tbm) n. A

system of justice in which the judges play an active

role. They may investigate the case and question witnesses. It is different from an accusatorial system in

which the two parties present all the evidence and the

judge serves as a referee.

legalism (LEb gbl iz bm) n. A word or expression

used exclusively in law. Legal jargon.

monarchy (MON er keb5) n. A government led by a

king or queen.

National Convention (NA shbn l kbn VEN shbn) n.

The new name of the National Assembly, the first

government of the French Revolution.

penal (PEb5 nbl) adj. Subject to punishment. A penal

code is a list of laws defining crimes.

primogeniture (pribmob5 JEN b ter) n. The right of the

eldest son to inherit all the property of his parents.

public policy (PUB lbk POL b seb5) n. A principle,

plan, or course of action that a government adopts

to address social, economic, or other problems.

secular (SEK yb lbr) adj. Related to government; not

related to religion.

testimony (TEST b mob5 neb5) n. Statements made by

witnesses under oath.

Pronunciation of Names

Augeas (b JEb5 bs) The king of Elis who held his enormous herds in his Augean Stables. As one of his 12

labors, Hercules cleaned the stables in one day by

making a river flow through them. (From Greek

mythology.)

Cambaceres (kom bb SAb5 res) Jean Jacques Regis de

Cambaceres (1753–1824), a French legal scholar and

supporter of the revolution who served as second

consul in the Consulate.

Napoleon (nb POb5 leb5 bn) Napoleon Bonaparte

(1769–1821), general, first consul, and emperor of

France.

Portalis (por tol Eb5S) Jean-Etienne-Marie Portalis

(1746–1807), a lawyer and proponent of Roman law

who was one of the drafters of the Code Napoleon.

Pothier (POb5 theb5 ab5) Robert Joseph Pothier (1699–1772), a

legal scholar who wrote books before the revolution

reconciling Roman, customary, and canon law.

Robespierre (ROb5BZ peb5 är) Maximilien Robespierre

(1758–94), the leader of the French Revolution who

oversaw the reign of terror.

Stendhal (sten DOL) Pen name of Marie Henri Beyle

(1783–1842), the French novelist best known for writing The Red and the Black.

Toulon (tew LOb5N) A city in southeastern France on

the Mediterranean Sea.

Tronchet (TROb5N shab5) François Denis Tronchet

(1726–1806), a trial lawyer and advocate of customary

law who was one of the drafters of the Code Napoleon.

Voltaire (vob5l TÄR) The pen name of the French

philosopher and writer François Marie Arouet

(1694–1778).

Waterloo (WOT br lew) A city in Belgium that in

1815 was the battle site of Napoleon’s final defeat.

Pronunciation Key: bat, ab5te, are, däre, den, eb5go, new, her, bit, ib5ce, îrritate, box, nob5, born, oil, out, but,

ub5se, chum, she, thin, the, zh sound in treasure or mirage; b is the uh sound in unaccented syllables.

49

Of Democrats & Dictators

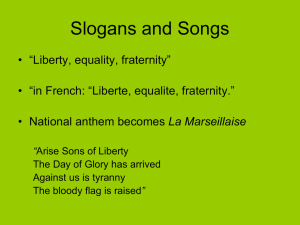

Lesson 8

The French Revolution

Overview

This lesson introduces students to the revolution and Napoleon.

First, students read about and discuss the French Revolution. Then in small groups, students create an

updated Declaration of the Rights of Man. Finally, students read about and discuss Napoleon.

Preparation

Objectives

Students will be able to:

Preparation

• Explain why it was an act of rebellion for the

representatives of the third estate to declare

themselves the National Assembly.

Readings in the student text:

• “The French Revolution,” pp. 40–43

• “Napoleon,” p. 44

• Identify the different governments of France

following the revolution.

Activity in the student text: “A New Declaration

of Rights,” p. 43

• Decide on five rights that they consider most

important and justify their importance.

Of Democrats & Dictators

50

Procedure

I. Focus Discussion

A. Tell students that some events in history are considered terribly important. Hold a brief discussion

by asking students: What do you consider the most important events in world history?

Accept various answers, but ask students to justify their choices with reasons.

B. Tell students that historians consider the French Revolution one of the most significant events in

history. Explain that they are going to begin a unit on the Code Napoleon, one of the most influential systems of law today, which was developed following the revolution.

II. Reading and Discussion—The French Revolution

A. Tell students that the unit’s vocabulary words with pronunciations are on page 41.

B. Ask students to read “The French Revolution,” pages 40–43. Ask them to look for the forms of government before and during the revolution.

C. When students finish reading, hold a discussion using the questions on page 43.

1. What was the third estate? When its representatives declared themselves the National Assembly,

why was this an act of rebellion?

The seldom-used national legislature was divided into three bodies, known as estates. The

first estate was the clergy, the second the nobility, and the third estate consisted of all the

remaining people in France.

By declaring the meeting of the third estate the National Assembly, it was violating hundreds of years of tradition and disobeying a direct order from the king. This was rebellion.

2. What were the different governments of France following the revolution? Name something

important that happened during each. Which do you think was most important?

• National Assembly. It passed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and also declared

war on Austria.

• National Convention. It created a people’s army and condemned the king and queen

to death.

• The Committee on Public Safety. It presided over the reign of terror.

• The Directory. It found Napoleon, a general who could win the war.

As for which event was most important, accept reasoned responses.

III. Small-Group Activity—A New Declaration of Rights

A. Explain that the French National Assembly wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Man in 1789. Tell students that they are going to get an opportunity to write their own declaration of rights. Explain that

they can use the Declaration of the Rights of Man (on page 42) to give them ideas, but it is more than

200 years old, and they should try to come up with rights that they think are important to them today.

B. Divide the class into groups of four or five students. Ask students to read “Activity: A New

Declaration of Rights,” on page 43. Go over the instructions and answer any questions that students

may have.

51

Of Democrats & Dictators

C. When the groups have completed listing their rights, call on one group to report its five rights and

why it chose them. Call on other groups and hold a class discussion of the rights and which rights

students consider most important.

IV. Reading and Discussion—Napoleon

A. Tell students that during the revolution a general gained fame and eventually seized power,

Napoleon Bonaparte. Ask students to read “Napoleon,” page 44. Ask them to look for things that

Napoleon accomplished by 1802 and to think about which things they think were most important.

B. When students finish reading, hold a discussion using the questions on page 44.

1. What did Napoleon accomplish by 1802? Which of these accomplishments do you think was

most valuable? Why?

Napoleon accomplished the following by 1802:

• He put down an attempt to restore the monarchy.

• He led the French army to many victories.

• He seized control of the French government.

• He appointed competent people to run the country.

• He set up the nation’s first public education system.

• He completed many public works projects.

• He signed peace treaties with many nations.

As for which was most valuable, accept reasoned responses.

2. What did Napoleon include in his plan to unify the French nation? Why do you think this

would help unify the nation?

He planned to write a code of laws.

As for why a code of laws might unify the nation, the country had just gone through a

major revolution and wars, the code might settle some issues brought forward during the

revolution. Accept other reasonable answers.

Of Democrats & Dictators

52

Lesson 9

Making the Code

Overview

This lesson explores what the law in France was like before the Civil Code and how the code was made.

First, students read about and discuss the law in France before the Civil Code. Then they read about

and discuss how the code was made. Finally, in small groups, students examine proposed rational

reforms and decide whether such reforms would stand a chance of being enacted in today’s world.

Preparation

Objectives

Students will be able to:

Readings in the student text:

• Identify the conflicting legal systems in

France before the revolution.

• “The Law in France Before the Code,” pp.

45–46

• Identify who wrote the Civil Code and

explain why Napoleon chose them.

• “Making the Code,” pp. 46–48

Activity in the student text: “Rational Reforms,”

pp. 48–49

• Analyze proposed rational reforms and determine their practicality.

53

Of Democrats & Dictators

Procedure

I. Focus Discussion

A. Hold a brief discussion by asking students:

• Who was Napoleon?

Napoleon was a highly successful general who seized control of the government during the

revolution.

• Napoleon planned to write a new code of laws to unify the French nation. What problems or

difficulties do you think he might encounter in trying to draft such a code?

Accept reasonable responses.

B. Tell students that before the French Revolution the law in France was in disarray.

II. Reading and Discussion—The Law in France Before the Code

A. Ask students to read “The Law in France Before the Code,” pages 45–46. Ask them to look for:

• The different systems of law in France.

• Attempts to change the law.

• Forces resisting changing the law.

B. When students finish reading, hold a discussion using the questions on page 46.

1. The French philosopher Voltaire wrote: “When you travel in this kingdom, you change legal

systems as often as you change horses.” Give examples of what he meant. What problems

might this cause?

In France before the revolution, the following morass of legal systems existed:

•

•

•

•

•

•

Roman law in the south.

Customary law in the north with hundreds of different versions.

Feudal landowners insisted on their own rules.

Catholic Church set rules for marriage, divorce, and even some crimes.

Royal edicts and ordinances.

Case law from law courts.

Possible problems:

• People unsure of the law.

• Conflicts as to what the law is.

• Inconsistency.

• One court not accepting the rulings from another area.

Accept other reasonable answers.

2. Before the revolution, what attempts had been made to reform French law?

• French kings had enacted ordinances on crimes, commerce, sea trading, gifts, wills,

and inheritance.

• French legal scholars had tried to create model codes.

Of Democrats & Dictators

54

3. What forces resisted the reforms?

Two main forces opposed change:

a. Nobles who wanted to retain firm control on their lands.

b. Judges who saw a code as a threat to their privileges.

4. After the revolution, the opposition to reform was gone. Why do you think a new code was not

enacted?

The French revolutionary governments wanted a simple, rational code, but when presented

on four separate occasions with different proposals for a code, the government did not

accept any of them. The best explanation for their rejection is probably that it is not an

easy task to create a simple, rational code that members of a legislature can agree on.

III. Reading and Discussion—Making the Code

A. Tell students that it took great effort to change the law and create a new code. Ask students to read

“Making the Code,” pages 46–48. Ask them to look for:

• Who wrote the code.

• Why they were chosen to write it.

• The type of code they wanted.

B. When students finish reading, hold a discussion using the questions on page 48.

1. Who wrote the Civil Code? Why do you think Napoleon chose those people?

The Civil Code was written by a committee of four men, all of them middle-aged or older

and conservatives or moderates. Two were experts in Roman law and the other two in customary law. But they all believed in Enlightenment concepts.

Napoleon chose them because he wanted the code to be accepted by as many people as

possible. He wanted to forge a compromise between supporters of Roman law and supporters of customary law. He wanted a code reflecting ideas of the Enlightenment that moderates and conservatives could support.

2. Why do you think the drafters did not want a detailed code?

Their stated reason was that a code should reflect general principles of law and judges

should apply these principles to particular cases.

Accept other reasoned responses.

3. The Civil Code is sometimes called the Code Napoleon. Which do you think is the better

name for the code? Why?

Reasons why it should be named after Napoleon: It was his idea. He appointed the four

men who wrote the code. It was said that the drafters wrote the code with him in mind, an

intelligent layman. Napoleon sat through and even guided the long meetings of the

Council of State reworking the draft of the code. When the legislative process seemed to

block the code’s passage, Napoleon maneuvered to make sure it was passed. Without him,

there would not have been a code. In almost every sense, it was his code.

Reasons why it should not be named after Napoleon: He did not create or write the code.

He admitted great ignorance on matters of law. The Civil Code is a better description of

the code.

55

Of Democrats & Dictators

IV. Small-Group Activity—Rational Reforms

A. Tell students that the Civil Code was one of many French Revolution reforms attempting to make

life more rational. Tell them that they are going to get an opportunity to examine some proposed

rational reforms for today’s world.

B. Divide the class into seven groups and number each group from one to seven. Tell students that the

number they receive is the number of the reform they are assigned. Ask students to read “Activity:

Rational Reforms” on page 48 and ask the groups to read their assigned reform. Emphasize that

none of the questions (except what the reform is) is answered in the description of the reform. Tell

students that they must think to figure out the answers. Answer any questions that students may

have and give them time to complete the activity.

C. When students finish, call on one group to report and answer the questions. Hold a class discussion

on the answers. Repeat this process for all seven groups. Below are some comments on each of the

reforms:

1. The Metric System. Many attempts have been made to introduce the metric system to the

United States. In 1975, Congress passed the Metric Conversion Act “to coordinate and

plan the increasing use of the metric system in the United States.” But it did not mandate

conversion; it only sought voluntary efforts. These efforts fizzled out. The most significant area of metrification thus far is in the U.S . military and in scientific laboratories. In

daily life, liter bottles have entered stores, but English measures remain the norm.

2. Celsius Scale. The Celsius scale has met the same fate as the metric system in the United

States. Proponents of the Fahrenheit scale argue that it is more human-based than the

Celsius scale. On the Fahrenheit scale, a very hot day is 100 degrees and a very cold day is

0 degrees.

3. Dvorak Keyboard. The resistance to this keyboard probably comes from a lack of demand for

the conversion and manufactures who see no need to push further than they have already

gone. The question is why more schools do not teach the Dvorak keyboard. In a few years

when voice recognition becomes better, people may not use keyboards to input information.

4. Simplified Spelling. Resistance comes from those who have already learned English

spelling and do not want to learn a new system and from those who think the current system is fine and shows the etymology of words. The radical reforms of changing the alphabet have no hope. It’s more likely that spelling will be simplified gradually over time.

5. Reformed Calendar. The problem with this reform is that few think there is a problem

worth changing the calendar over. Many countries in the world use the current system. To

change, it would require differing from these countries or trying to get other countries to

go along with the change.

6. Esperanto. Today, many see the desirability of a universal language. English is the closest

we have. It is the official language in about 30 countries. It is the language of airline

pilots, and increasingly it is becoming the language used by academics in research. But if

the economic dominance of the United States should falter, the use of English may also

stop growing. In any case, it seems unlikely that Esperanto will become adopted. Most

people want to learn a language that people are actually speaking. Perhaps technology will

create a translating device that will allow people to communicate across languages.

Of Democrats & Dictators

56

7. Plain Legal Language. This reform is taking hold, especially in jury instructions, which are

more and more frequently being written in plain language. One source of resistance to plain

legal language in legal documents is from lawyers who are reluctant to change language that

has worked in the past. If they change from something that has worked to something new,

they risk lawsuits. Many legal terms have been litigated, their meaning has been settled by

courts, and there are books on words and phrases and their legal meaning.

D. Debrief the activity by holding a discussion on these questions:

• Which, if any, of these reforms do you think should be enacted? Why?

• Which of these reforms do you think holds the most promise of being enacted? Why?

• Which type of reform do think is better—one that makes small changes over time or one that

makes one great change? Why?

57

Of Democrats & Dictators

Lesson 10

The Civil Code

Overview

This two-day lesson examines the contents of the code, its legacy, and the differences between the Civil

Code and common law.

On day one, students read about and discuss the contents of the Civil Code. Then in small groups,

students apply the law of torts found in the Civil Code to hypothetical cases.

On day two, students read about and discuss the legacy of the Civil Code. Then they read about and

discuss the differences between the Civil Code and common law. Finally, in small groups, students role

play advisors to an emerging democracy and advise whether or not the country should adopt the jury

system.

Preparation

Objectives

Students will be able to:

Day One

• Identify remarkable aspects of the Civil Code.

Reading in the student text: “The Civil Code,”

pp. 50–52

• Identify revolutionary and conservative

aspects of the Civil Code.

Activity in the student text: “Torts and the

Code,” p. 53

• Decide hypothetical torts cases based on the

law in the Civil Code.

Day Two

• Cite the influence of the Civil Code and

express a reasoned opinion on why it has

been so influential.

Readings in the student text:

• “The Code’s Legacy,” p. 54

• “Differences Between the Civil Code and

Common Law,” pp. 55–56

• Identify the major differences between the

Civil Code and the common law and express

a reasoned opinion on which are most significant.

Activity in the student text: “Is the Jury System

Outdated?” p. 57

• Analyze the pros and cons of the jury system

and express a reasoned opinion on whether a

new democracy should adopt the jury system.

Of Democrats & Dictators

58

Procedure

Day One

I. Focus Discussion

A. Hold a brief discussion by asking students: What codes of laws do you know about?

Students now know about the making of the Civil Code. They may respond with other historical codes such as the Code of Hammurabi and Justinian’s Code.

Students may be more familiar with their own state’s Motor Vehicle Code and Penal Code

(criminal code).

In fact, codes are quite common in the United States. The state of California alone produces

the following codes (each a thick book): Business and Professions, Civil, Civil Procedure,

Commercial, Corporations, Education, Elections, Evidence, Family, Financial, Fish and Game,

Food and Agricultural, Government, Harbors and Navigation, Health and Safety, Insurance,

Labor, Military Veterans, Penal, Probate, Public Contract, Public Resources, Public Utilities,

Revenue and Taxation, Streets and Highways, Unemployment Insurance, Vehicle, Water, and

Welfare and Institutions.

B. Explain that the Civil Code created through Napoleon’s efforts is considered one of the most

remarkable documents in history.

II. Reading and Discussion—The Civil Code

A. Ask students to read “The Civil Code,” pages 50–52. Ask them to look for:

• What is remarkable about the code.

• Its revolutionary aspects.

• Its conservative (or even reactionary) aspects.

B. When students finish reading, hold a discussion using the questions on pages 52–53.

1. Many have called the Civil Code a “remarkable document.” What do you think they might be

referring to?

Among the things about the code that people consider remarkable are:

• Its length. The whole code could fit into a small paperback book.

• Its clarity.

• Its literary merit.

• Its reconciliation of tradition with change.

Accept other reasonable answers.

2. The Civil Code contains both revolutionary and conservative (even reactionary) elements. What

are examples of both in property law? In family law?

Property law:

Revolutionary:

59

Of Democrats & Dictators

• Eliminated all feudal restrictions on land and contracts.

• Made sales of property complete when there was a “meeting of the minds.”

• Eliminated feudal practice of primogeniture.

Conservative:

• Restricted willing away property.

• Eliminated the revolution’s land registry system.

Family law:

Revolutionary:

• Allowed divorce.

• Set up a governmental system of recording births, deaths, and marriages.

• Put the state in charge of marriage, not the church.

Conservative:

• Restricted divorce by making it cumbersome.

• Made husband head of the family. Limited freedom of wife.

• Limited the freedom of young people to marry.

• Put father in complete control of children. He could even jail them.

• Banned investigations of who was the father of an illegitimate child.

3. There are two types of codes. One type clarifies and reorganizes the law, but basically restates

existing law. The other type reforms and remakes the law. Which type do you think the Civil

Code is? Why?

Accept reasoned responses.

4. French historian Albert Sorel wrote: “The Civil Code has remained . . . the French Revolution—

organized.” What did he mean by this statement? Do you agree with it? Explain.

The statement means that the code put many of the ideas of the revolution into a coherent, organized code of laws.

There is little doubt that the code is coherent and organized. The question is whether it

reflects the ideas of the revolution. Accept reasoned responses.

III. Small-Group Activity—Torts and the Code

A. Tell students that they are going to role play judges and decide five torts cases using the Civil Code.

Divide the class into groups of four or five students. Ask students to read “Activity: Torts and the

Code” on page 53. Answer any questions that students may have. Give them time to decide the

cases.

B. When students finish, call on one group to report its decision and reasoning on case #1. Hold a

discussion on the case. Repeat this process for the other cases. Below are some suggested answers on

the cases:

Of Democrats & Dictators

60

Case #1: Article 1383 says “Everyone is responsible for the damage he causes, not only by his

own act, but also by his negligence or by his imprudence.” The question is who caused the

fire—Jay who spilled the gasoline or Walt who threw down a lit cigarette or both of them? Were

they negligent or imprudent? Clearly Jay was. He had time to see the signs. Walt may not have

had time to read the signs (or maybe he read them and tried to extinguish his cigarette), but

should he not have known better than to have a lit cigarette in a gas station? Accept reasoned

answers.

Case #2: Again: “Everyone is responsible for the damage he causes . . . .” Ken caused the damage by jumping out of the taxi, but was he negligent? Under U.S . law, Ken would not be held

responsible. In the 1941 case of Cordas v. Peerless Transportation Company, 27 NYS 2nd 198, a

similar set of facts presented themselves to the court. The court stated: “If under normal circumstances an act is done which might be considered negligent, it does not follow as a corollary that a similar act is negligent if performed by a person acting under an emergency, not of

his own making, in which he suddenly is faced with a patent danger with a moment left to

adopt a means of extrication.” Accept reasoned responses.

Case #3: If you light candles and leave them unattended, this seems like negligence and it is

foreseeable that a fire fighter might get injured in the ensuing fire. It seems like a reasonable

interpretation of the code to hold Mel responsible for compensating Jane. Point out that this

would not be true under U.S . law. Most states adhere to the “firefighters rule” that denies

compensation to firefighters for two reasons: (1) they are professionals who assume the risk of

fighting fires and (2) letting them sue the people who caused the fire might deter people from

calling the fire department.

Case #4: This is a tricky one because the code says a person must cause the damage. Clearly,

one of the two caused the damage, but it is not known which one. A similar problem presented itself in the 1948 case of Summers v. Tice (199 P2nd 1). In that case, the California court

decided that since the plaintiff had proved one of the two had caused the harm, it was up to

each defendant to prove he did not cause the harm. If a defendant could do this, then the

defendant would not be held liable. Otherwise both would be considered liable for the harm.

Case #5: Another tricky one. Did Tess in any way cause the harm? Or did she simply not do

anything to stop the harm? Is this “imprudence” under the code? In most jurisdictions in the

United States, there is no liability for failing to rescue someone even when it would be easy to

do. There is great debate on this issue, and some jurisdictions are moving away from the rule

against liability for failing to rescue another person.

C. Debrief the activity by asking students:

• Which of these cases was the easiest to decide? The most difficult? Why?

Accept reasoned responses.

• Did the Civil Code provide you with enough guidance to decide the cases? Why or why not?

If students arrived at different answers, this might indicate the code did not have enough

specificity (but even with more detailed laws, debates often arise).

• Do you think it would be better to have a code that stated the law in greater detail? Explain.

Accept reasoned responses.

61

Of Democrats & Dictators

Day Two

IV. Focus Discussion

A. Remind students that they have been studying the French Civil Code. Hold a brief review by asking

students:

• What are some of more remarkable aspects of the Civil Code?

As previously mentioned: its length, clarity, literary merit, and reconciliation of tradition

with change.

• What were some the code’s revolutionary elements?

In property law, it:

• Eliminated all feudal restrictions on land and contracts.

• Made sales of property complete when there was a “meeting of the minds.”

• Eliminated feudal practice of primogeniture.

In family law, it:

• Allowed divorce.

• Set up a governmental system of recording births, deaths, and marriages.

• Put the state in charge of marriage, not the church.

• What were some of its conservative and even reactionary elements?

In property law, it:

• Restricted willing away property.

• Eliminated the revolution’s land registry system.

In family law, it:

• Restricted divorce by making it cumbersome.

• Made husband head of the family. Limited freedom of wife.

• Limited the freedom of young people to marry.

• Put the father in complete control of his children. He could even jail them.

• Banned investigations of who was the father of an illegitimate child.

B. Tell students that they are going to look at the influence of the Code Napoleon.

V. Reading and Discussion—The Code’s Legacy

A. Ask students to read “The Code’s Legacy,” page 54. Ask them to look for how influential the code

has been.

B. When students finish reading, hold a discussion using the questions on page 54.

1. What has been the influence of the Civil Code? Why do you think it has been so widely adopted?

The Civil Code has been used as a model in many nations throughout the world: Most of

Europe and Latin America have adopted versions of the code. Many countries in other

areas have adopted it as well.

Of Democrats & Dictators

62

Its influence has extended to the United States. Louisiana uses a version of it. Throughout

the United States, which uses common law, codes of laws have been adopted.

Reasons for its adoption: It is a clear, succinct statement of law. It is compiled in one

place, unlike the common law. Accept other reasoned responses.

2. From what you know about Napoleon, do you agree that his most lasting legacy is the Civil

Code? Why?

Accept reasoned answers.

VI. Reading and Discussion—Differences Between the Civil Code and Common Law

A. Ask students to read “Differences Between the Civil Code and Common Law,” pages 55–56. Ask

them to look for the differences between the common law and Civil Code and think about which

are most important.

B. When students finish reading, hold a discussion using the questions on page 56.

1. Which of the six basic differences between the systems of law do you think is most important?

Which is least important? Why?

Accept reasoned responses.

2. If you were advising a new nation, what system of law would you advise the nation to adopt?

Why?

Accept reasoned responses.

3. Napoleon expressed dismay that people were interpreting the Civil Code: “The code had hardly

appeared when it was followed almost immediately . . . by commentaries, explanations, developments, interpretations, and what not. . . . I was in the habit of saying to the Council of State:

Gentlemen, we have swept out the stable of Augeas. For heaven’s sake, let us not clutter it anew!”

One of the first commentators was a drafter of the code. He was the first of many. If the code

could fit into a small book, the commentaries would require a library. What did Napoleon mean

by his statement? Why do you think the code has spawned so much commentary?

Napoleon’s statement referenced the stable of Augeas, an allusion to one of the mythological labors of Hercules. (Hercules had to clean out the immense stable in one day, which

he accomplished by diverting a river.) Napoleon felt that they had just gotten rid of a tangled mess of laws and did not see why people were writing commentaries, which would

just confuse things anew.

Reasons why the code spawned so much commentary:

• All law spawns commentary. It is part of every legal system.

• The Civil Code just gave general principles, which invited commentators to fill in how

these principles should be applied in practice.

63

Of Democrats & Dictators