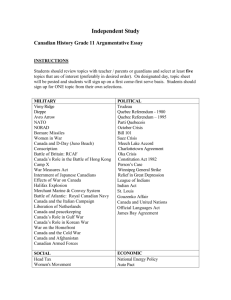

Canadian Military History Since the 17th Century

advertisement