Contract Law - Carpe Diem

advertisement

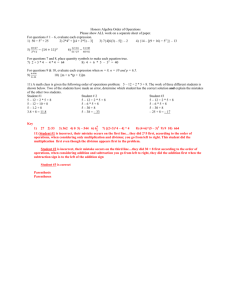

CQUniversity Division of Higher Education School of Business and Law LAWS11062 Contract Law B Topic 1 Mistake Term 2, 2014 Anthony Marinac © CQUniversity 2014 1 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction to Contract Law B ........................................................ 3 1.1 Objectives ......................................................................................... 4 1.2 Introduction .................................................................................. 5 1.1 Prescribed Reading .......................................................................... 7 1.2 Key Terms ........................................................................................ 7 2.0 Unilateral Mistake ........................................................................... 8 2.1 Mistake as to the subject matter ...................................................... 9 2.2 Mistake as to the identity of the other party ..................................11 2.3 Mistake as to the nature of the document ..................................... 14 2.4 Review questions ........................................................................... 16 3.0 Common Mistake ............................................................................ 18 3.1 Mistakes as to the existence of the subject matter: res extincta ... 20 3.2 Mistakes as to title: res sua ........................................................... 22 3.3 Equitable remedies for common mistake .....................................23 3.4 Review questions ........................................................................... 25 4.0 Mutual Mistake ...............................................................................26 4.1 Review question ............................................................................ 28 5.0 Review ............................................................................................ 28 6.0 Tutorial Problems ...........................................................................29 7.0 Debrief............................................................................................ 30 2 Topic 1 Mistake 1.0 Introduction to Contract Law B Welcome back, everybody, to your second term of the study of contracts. In Contract A we focused on the issues of formation of contracts, and the interpretation or construction of contractual terms. This term, we complete the picture by looking much more at what happens in contract law when a contract goes wrong. To my mind, the material we cover in this second term is quite a bit more interesting than the material be covered in Contract A. In the cases in this term, we see more parties in deep conflict, and much more fascinating legal reasoning is required in order to resolve those conflicts. The term will be divided generally into four parts: Part one will occupy us from topics 1 through to topic 5. During this part we will explore the topic of vitiation, which is a jargon term referring to circumstances in which the court will decide that a contract has never been effective. As you can imagine, this leads to serious legal difficulties when one or both parties have been carrying out what they understood to be their obligations under contract. We look at issues such as mistake, misrepresentation, misleading and deceptive conduct, unconscionable conduct, duress and undue influence, and a very curious legal concept called estoppel. Part two is our skills part, and will be covered in topic 6. During this topic, we will spend a week looking at how we find 3 the law and how we decode the system of legal citations. We will be looking far further than simply the CLR series, and we’ll look at the British citation system, the Canadian and New Zealand citation systems, and some of the citation process is in the United States of America. We will also look briefly at citation processes for the United Nations, the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court, and tribunals within the European Union. Part three examines the termination of contracts, and the remedies which a court may apply to do justice to an innocent party when a contract has been terminated. This is where things get really interesting, as we look at parties whose contracts have gone terribly wrong and who find themselves in serious conflict as a result. Part three will occupy us from topic 7 until topic 11. Finally, part four, which is covered in week 12, examines international and transnational contracts. Once upon a time, these were essentially a specialist concept, because relatively few people (generally those involved in business) were involved in international contracts. Nowadays, however, everyone who buys a book from Amazon or who buys cheap products on overseas websites, is engaging in international or transnational contracts. It is therefore important that we begin to establish a basic understanding of how such contracts differ from simple domestic contracts. 1.1 Objectives After studying Topic 1 you should be able to demonstrate: 4 An understanding of the difference between unilateral mistake, common mistake and mutual mistake; and The approach which is taken by the common law to circumstances where there is a mistake in the contract; and The approach which is taken by equity law to circumstances where there is a mistake in the contract. 1.2 Introduction If there is one thing that I have learned through bitter experience, it’s this: “Mistakes happen.” Mistakes happen in contracts so often that there is an entire branch of contract law devoted to unravelling them! Consider the following examples: Maria offers Stephen $200 to tutor her in Contract A. She says “I know you got a High Distinction, so you obviously know what you’re doing.” Stephen has no idea why she believes he got a high distinction, as he only got a Pass, but he wants the $200 and agrees to tutor. Susan tells Eric that if he collects her dry cleaning, she will take him to see the movie “Grease” at a local cinema. Eric agrees, and collects the dry cleaning. However, the nostalgia cinema had ceased playing the movie a week before Susan made her offer. Neither Susan nor Eric knew that the movie had stopped playing. Kahlia is a champion ballroom dancer in both the modern and Latin styles. She owns a beautiful white flowing modern ballroom dress, and a very daring and racy white Latin dress. Antoinette approaches Kahlia, who was wearing the Latin dress, and says “I’d like to buy your white dress for $1200.” Kahlia is hard up for cash, so she agrees, thinking that Antoinette intended to buy the white 5 dress Kahlia was wearing. In fact, however, Antoinette wished to buy the other white dress. Can you see how we need to recognise in these circumstances, one or both parties have made a mistake? And yet the mistakes are a little bit different. In the first case, Maria is the only one who has made a mistake, and Stephen knows she has made a mistake. In the second case, Susan and Eric make the same mistake. In the third case, it is very difficult to tell who has made the mistake but one thing is clear: the two parties have not really come to an agreement about anything at all. How should the law resolve these different situations? In fact, if you think about it, it is worth asking whether the law should attempt to resolve the situations at all. If Maria has made a mistake about Steven’s grade, isn’t that her problem? If Susan and Eric made an agreement to see a movie which is no longer playing, isn’t that a matter for them to sort out? Shouldn’t Kahlia and Antoinette have been more careful to ensure they both knew which dress they were talking about? After all, once the contract is formed both sides should be able to proceed with certainty that the contract will be enforced, right? What happens to freedom of contract if the law rushes in to fix things retrospectively because someone made a mistake? In reality, courts are reluctant to intervene on the grounds of mistake. The court takes the view that the parties have agreed to the same terms on the same subject matter. They have willingly undertaken the risk that they may have made a mistake. The law may even place the risk on one of the parties by applying principles such as caveat emptor (let the buyer beware) or caveat venditor (let the seller beware) according to the demand of commercial certainty. 6 So this is our first lesson in terms of mistake: oftentimes, the law will not intervene. Don’t always be in a huge rush to assume that just because a party has made a mistake the law will come to the rescue. However under some circumstances the law will intervene, and this week we will look at those circumstances. 1.1 Prescribed Reading Lindy Willmott, Sharon Christensen, Des Butler and Bill Dixon, Contract Law (Australia Oxford University Press, 4th ed, 2013) ch. 14. Cundy v Lindsay (1878) 3 App Cas 459 Great Peace Shipping v Tsavliris Salvage [2003] QB 679 Leaf v International Galleries [1950] 2 KB 86 Lewis v Averay [1972] 1 QB 198 McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission (1951) 84 CLR 377 Petelin v Cullen (1975) 132 CLR 355 Raffles v Wichelhaus [1864] 159 ER 375 Slee v Warke (1949) 86 CLR 271 Solle v Butcher [1950] KB 671 Taylor v Johnson (1983) 151 CLR 422 XCB Pty Ltd v Creative Brands Pty Ltd [2005] VSC 424 1.2 Key Terms 7 Common Mistake: A circumstance in which both parties make the same mistake in relation to a contract. Inter Praesentes: “Between those who are present”. A contract made inter praesentes is made between parties who are physically in the same place when the contract is made. Mutual Mistake: A circumstance in which both parties make a mistake in relation to the contract, but they make different mistakes. The effect is usually that the parties are never ad idem. Non est factum: “It was not my deed”. A person may claim non est factum if they did not know they were signing a contractual document when they signed; that is, they have made a mistake as to the nature of the document. Res extincta: “The thing no longer exists”. The subject matter of a contract is said to be res extincta if it has been lost, destroyed etc prior to the time of contract formation. Res sua: “The thing is mine”. Used to describe a situation where a person purports to contract for something which, it turns out, is already theirs by right. Unilateral Mistake: A mistake in circumstances where only one party to the contract makes the mistake, but the other party knows or ought to know that the mistake is being made. 2.0 Unilateral Mistake The first type of mistake we will discuss is known as a unilateral mistake. Look again at the tale of Maria and Stephen which was discussed above: 8 Maria offers Stephen $200 to tutor her in Contract A. She says “I know you got a High Distinction, so you obviously know what you’re doing.” Stephen has no idea why she believes he got a high distinction, as he only got a Pass, but he wants the $200 and agrees to tutor. This is a unilateral mistake. A unilateral mistake occurs when the following conditions are true: a) One party, and one party only, makes a mistake; and b) The other party knows, or ought to know that the first party has made a mistake. Both of these conditions are important. In the example given above, if Stephen had actually gotten a High Distinction there would obviously be no mistake at all. Furthermore, if Maria had simply approached Stephen out of the blue and asked him to tutor her without stating her understanding about his previous high-grade, there would be no reason why he should not simply accept her offer. The circumstances which seem to call on the law to intervene are the combination of the mistake on one hand, and the knowledge of the other party that the mistake was being made. So, how does the law deal with situations in which a unilateral mistake has been made? The first thing the law does is break down the unilateral mistake into one of three categories: a mistake as to the subject matter of the contract; a mistake as to the other party to the contract: or a mistake as to the nature of the contractual document. Let’s look at each of these in turn. 2.1 Mistake as to the subject matter The classic Australian example of mistake as to subject matter arose in a case called Taylor v Johnson (1983) 151 CLR 422. In 9 this case, Mrs Johnson gave to Mr Taylor an option to purchase a parcel of land for a specified price. Mrs Johnson believed that the sale price was to be $15,000 per acre. In fact, she was mistaken and the option specified the sale price to be $15,000 total. When this came to light, Mrs Johnson refused to go through with the sale, and Mr Taylor sued to force her to perform the contract. In its decision, the High Court made a number of important statements about how these unilateral mistakes will be treated by the court. First and foremost, the test to be applied will be an objective test, not a subjective test. As a result, the mere fact that one party feels they made a mistake about the subject matter is not enough to prove the mistake. The court will ask whether a reasonable observer would also conclude that a mistake had been made. Second, the court distinguishes between the approaches of the common law and equity law in dealing with a situation such as this. Common law would hold, in these circumstances, that the mistake was irrelevant. Common law would find that Mrs Johnson had not undertaken sufficient care and attention, and she must suffer the consequences. The court found that equity law, however, took a slightly different approach. You will no doubt recall from previous study that equity law is more closely aligned to the law of conscience. The High Court found that equity would rescind (set aside) the contract in this case, but only because Mr Taylor had taken deliberate steps to prevent Mrs Johnson from becoming aware of her mistake. As a result, equity law will intervene in a case of unilateral mistake as to the subject matter of the contract when the following three conditions hold true: 10 a) The mistake must relate to a fundamental matter of the contract; b) The other party must know of the mistaken party’s mistake; and c) The other party must take some steps to prevent the mistaken party from learning of their mistake. The third of these conditions was sharpened somewhat in the case of XCB Pty Ltd v Creative Brands Pty Ltd [2005] VSC 424, in which the Victorian Supreme Court found that the other party’s conduct must amount to more than simply failing to correct the other party’s mistake: it must amount to an unconscionable effort to prevent the other party from becoming aware of the mistake. www.letan.com.au Context: Le Tan was a trading name for Creative Brands Pty Ltd 2.2 Mistake as to the identity of the other party In many circumstances, the identity of the other party to a contract is an important element of the contract itself. For instance, we may intend to contract with a particular party because of their reputation, their skill, our history of dealings together, their credit worthiness, or some other factor personal to themselves. This is perfectly reasonable. Under those 11 circumstances, a mistake as to the identity of the other party may be an important mistake. The law subdivides these mistakes into two types: mistakes where parties are not face-toface whilst conducting contract formation; and contracts which are formed by two parties who are face-to-face. Let’s look at each in turn. 2.2.1 Parties not Face to Face If a mistake is made about the identity of the other party, and the contract is not made by parties who are face-to-face, the contract will typically be void. This is best understood by looking at the classic case on this issue, Cundy v Lindsay (1878) 3 App Cas 459. In this case a man named Blenkarn sent a letter to Lindsay offering to buy a consignment of more than 3000 handkerchiefs for a specified price. He wrote his letter in such a way as to make it appear that he was in fact writing on behalf of a company called “Blenkiron & Co” which had a very sound business reputation. In fact, Blenkarn then sold the handkerchiefs to Cundy and disappeared, refusing to pay Lindsay. Lindsay sued Cundy in the tort of conversion, essentially on the basis that Cundy had received what amounted to stolen goods. The court found in favour of Lindsay. The reasoning was that Lindsay had never intended to form any contract with Blenkarn. As a result, Lindsay and Blenkarn were never ad idem and so no effective contract for sale had ever been made. The handkerchiefs had never properly passed to Blenkarn, so he could not pass title in them to Cundy. 12 The result of this is that if one party makes mistake as to the identity of the other party, and the two are not face-to-face at the time, the contract is likely to be void. 2.2.2 Parties Face to Face (inter praesentes) The second situation occurs when two parties undergo sharing face-to-face. In legal Latin, the contract is said to be inter praesentes, or “between those who are present”. To understand how this situation works, let’s consider the case Lewis v Averay [1972] 1 QB 198. In this case a contract was formed for the sale of a car. The purchaser gave his name as “Richard Greene”, which was the name of a well-known actor who was famous for playing the role of Robin Hood. To support this identity, he presented a television studio pass bearing his name and an official-looking stamp. The seller accepted his identity and took a cheque for the car. The cheque subsequently bounced, and the seller turned out not to have been the actor after all. What should the court do in this situation? The court begins with a rebuttable presumption (revise the topic on intention to create legal relations from Contract A if you need to remind yourself about the effect of assumptions). The presumption is that each party intends to make a contract with a person who is standing opposite them. As a result, in this situation, the presumption would be that the seller intended to sell the car to the person who gave them the cheque, regardless of whether that person was in fact the actor Richard Greene. This presumption can be rebutted by showing sufficient evidence of an actual intention to undertake a contract with a specified person. So, in this case, if the seller had perhaps said 13 “I am only prepared to engage in this contract with you because you are the actor Richard Greene and if you were anyone else then I would not be prepared to engage in this contract with you” then this might have been sufficient to rebut the presumption. In Lewis v Averay, however, there was no such evidence that the contract was not held to be void due to unilateral mistake. Before you get too anxious about this, bear in mind that we still have to cover misrepresentation, and misleading and deceptive conduct, which are separate areas of contract law. Often the innocent party might have a remedy under these aspects of contract law, even if the court is not prepared to find that there was an actionable mistake. 12290336 2.3 Mistake as to the nature of the document 14 Finally, we ask how the court should treat a situation where a person enters into a contract, without any idea that they are doing so. For instance, what is the situation if a person believes that the document they are signing is merely a request for further information, or a receipt, or a bill of lading, or some other document which might occur in a commercial context but which is not contractual in nature? On the one hand, the rule in L’Estrange v Graucob, which we studied in Contract A, tells us that if a person has signed a document they are bound by it, even if they haven’t read it properly. This is an important role because it allows commercial parties to rely on a signature when a signature has been given. Would it be fair to allow the doctrine of mistake to do away with this reliability? The law deals with this issue by introducing a concept called non est factum, which translates as “this was not my deed.” If it is clear that the person had no concept that they were ever entering into a contract, then how can we say that the two parties were ever ad idem? And if they were never ad idem, then on what basis do we say there has been an agreement at all? The court has worked hard to balance these competing and important principles of contract law. The authoritative case for Australia is called Petelin v Cullen (1975) 132 CLR 355. In this case, Petelin was illiterate in English, and was very poorly proficient even in spoken English. He had extended an option to Cullen for the purchase of a parcel of land, but the option had expired and Cullen wrote, via an agent, seeking a further option and paying $50 for the option. Petelin was told by Cullen’s agent that he must sign the document, and he signed it believing it to be a receipt, not a contract. He later refused to sell the land. 15 The High Court found that the option was not binding upon Petelin, but in doing so it set out three rules which must be met: First, the person who claims that they have made the mistake must either be unable to read (for instance, through blindness or illiteracy in English) or must rely on another person to explain the document to them; or alternatively for some other reason they must be unable to understand the nature of the particular document. Second, the person must believe that the document is radically different from what it actually is. As a result, if the person who signed the document was even aware that the document was capable of creating obligations, the doctrine of non est factum will not apply. Finally, if the other party is innocent, the person making the mistake must show that their failure to read and understand the contract was not due to carelessness. Note, however, that if the other party is not innocent (for instance, if they have misrepresented the nature of the document) then this final criterion will not apply. If we apply these rules to Petelin v Cullen we can see that Petelin was unable to read English and relied upon the agent’s explanation of the document, so the first rule is met. He believed that the document was a receipt, and was thus radically different in nature to a contract, so the second rule is met. In this case the third rule did not have to be met because the High Court found that Cullen’s agent was not innocent, as he had effectively misled Petelin as to the nature of the document. 2.4 Review questions 16 Question 1 Which of the following is a unilateral mistake as to subject matter? a) the promisee is in error as to the date of delivery b) the promisor is in error as to the quantity to be delivered c) both parties are in error as to the customs implications of the contract d) one of the parties has adopted a fraudulent identity. Answer: (b) Question 2 What occurs when there is a mistake as to the nature of a party, and the parties are not face to face? (a) (b) (c) (d) the contract will be void the contract will be voidable the contract will be breached the contract will be frustrated Answer: (a) Question 3 The Latin term inter praesentes means: (a) (b) (c) (d) the exchange of presents or gifts between those who are present at the present time upon presentation 17 Answer: (b) Question 4 Which of the following is not a consideration for relief when a person has made a unilateral mistake as to the nature of a document? (a) the person making the mistake must show the mistake was not due to carelessness (b) the person making the mistake must be unable to read or understand the document (c) the person making the mistake must have been the victim of misrepresentation (d) the person making the mistake must believe the document is of a radically different nature. Answer: (c) 3.0 Common Mistake Recall, from this week’s introduction, the tale of Susan and Eric: Susan tells Eric that if he collects her dry cleaning, she will take him to see the movie “Grease” at a local cinema. Eric agrees, and collects the dry cleaning. However, the nostalgia cinema had ceased playing the movie a week before Susan made her offer. Neither Susan nor Eric knew that the movie had stopped playing. This situation is rather different from the unilateral mistakes we have been considering above. In this case, both parties have made the same mistake. Both parties have assumed that the movie would be playing and later found out that it was not. What should we do in this case? On the one hand, a simple 18 solution might be to declare the contract to be void. However, this might not be fair on Eric who has afterall kept his end of the bargain by collecting the dry cleaning. This situation is described in the law as a common mistake, where both parties make the same mistake. Read that sentence again, please. You’ll need to clearly understand it if you do not wish to be confused when we discuss mutual mistakes below. For a common mistake, both parties make the same mistake. The law in Queensland currently follows an English case called Great Peace Shipping v Tsavliris Salvage [2003] QB 679, which set out five rules for cases in which common mistake is alleged: First, there must be a common assumption (which turns out to be in error); Second, neither party must have given an undertaking that the circumstances are true; Third, neither party must be responsible for creating the error (for instance, by destroying the subject matter of the contract); Fourth, the mistake must render performance of the contract impossible; Fifth, the mistake may be made about the subject matter, or about vital circumstances surrounding the subject matter. We divide common mistakes into two general categories: those where a party has made a mistake about the existence of the subject matter (these are referred to in legal Latin as mistakes in the circumstances of res extincta); and, second, those where a party has made a mistake as to the title in the subject matter 19 (these are referred to in legal Latin as mistakes in the circumstances of res sua). Let’s look at each in turn. 3.1 Mistakes as to the existence of the subject matter: res extincta What do we do when two parties make a contract regarding some item, both believing the item to exist, but then later finding that the item does not exist. This is essentially the problem faced by Susan and Eric above. Screenings of Grease no longer exist. The classic case in this area of contract law is called McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission (1951) 84 CLR 377. As you can no doubt imagine, the early 1950s were a very busy time for anyone involved in shipping salvage operations. The collective warlike efforts of all major countries in the world had resulted in a great quantity of shipping lying at the bottom the ocean. At this time, the Commonwealth Disposals Commission, a government agency, called for tenders for companies who wished to purchase an oil tanker which was said to be lying on Jourmand Reef, slightly to the North of Papua New Guinea’s Milne Bay. McRae was the successful tenderer, and subsequently spent a great deal of money mounting a salvage operation. After this expense had all been incurred, they discovered that in fact there was no tanker lying on Jourmand Reef. To make matters worse, there was actually no reef called Jourmand Reef to begin with. If there wasn’t so much money at stake, this would count as comedy. If the Chaser gang made up a story along these facts, they’d be attacked for being unrealistic! What should occur in this situation? 20 3563486 The High Court considered whether this was a case of common mistake. After all, both sides of the contract had made the same mistake: both sides had assumed there was a place called Jourmand Reef, and both sides had assumed there was a tanker sunk on the reef. The court found, however, that this was not a case of common mistake. The reason for this was that the Commonwealth had certainly made a mistake, but then McRae had acted in reliance upon the Commonwealth’s statement. There was really only one mistake made: by the Commonwealth. As a result, the Commonwealth promised something it could not deliver and it was therefore in breach of the contract. This makes sense if we consider the criteria set out in Great Peace Shipping. There was, of course, a common assumption which turned out to be an error. However the Commonwealth had given an undertaking that the circumstances were true. As 21 a result, following the criteria in Great Peace Shipping, this was not a common mistake. Another case worth considering here is the case of Leaf v International Galleries [1950] 2 KB 86. In this case the gallery purchased a painting, believing it to be by a famous artist. In fact, it was a forgery. The seller provided the painting the contract stated he would provide, but of course it had nowhere near the value which it would have had if it had been the genuine article. Was this a mutual mistake? The court found that it was not, because the seller had contracted to sell a painting by the famous artist; the gallery had contracted to buy a painting by the famous artist; and the seller had failed to provide a painting by the famous artist. As a result, this was a case of breach rather than a case of mistake. 10950700 3.2 Mistakes as to title: res sua In this rare situation a mistake is made by both parties about the ownership of the goods in question. Under most circumstances, if it turns out that the seller does not actually own the item being sold, the principle nemo dat quod non 22 habet, or “You cannot give what you do not have” will apply. You will learn all about this in property law. However what about the rare situation where someone is sold something which they already own? In a case called Bell v Lever Bros [1932] AC 161, the English Court of Appeal remarked in obiter that such a case would be one of common mistake and would make a contract void. 3.3 Equitable remedies for common mistake As you will have learned during previous studies, rules of equity may provide more flexible solutions to contractual disputes than can be provided by the common law. Equity provides a number of remedies in cases of common mistake, which you must understand. 3.3.1 Recission First, and perhaps most obviously, equity can set aside the contract on whatever terms are considered appropriate. For this to occur, there must be a common mistake of the fundamental nature, and the party seeking to have the contract set aside must not be at fault in relation to the mistake. The authority for this remedy is Solle v Butcher [1950] KB 671, where both parties made a mistake about whether certain rent capping legislation applied to a flat. They later discovered that the rent cap should have applied, and the renter therefore had been paying too much rent. However the court found that the plaintiff had in fact served as an advisor to the owner in relation to the application of the legislation. As a result, the plaintiff (who was seeking to have the contract set aside) was at fault in relation to the mistake and it would have been inequitable to allow them to benefit from the mistake. 23 Instead, the court rescinded the contract and ordered that a new contract be set in place for the proper amount of rent going forwards. 3.3.2 Rectification The second option the court may use is to rectify the contract, in circumstances where it may be possible to undo the mistake and allow the contract to carry on. The effect of this would be to change the contract so that it properly reflects the actual intentions of the parties. This situation would be unusual, but is possible. An example can be found in the case Slee v Warke (1949) 86 CLR 271 which related to an option for the sale of this pub: www.museumvictoria.com.au In this case, the drafter of the contract use the word “may” in circumstances where it was clear that both parties understood that the word “shall” would have been more appropriate. When you get to Advanced Statutory Interpretation and Legal Drafting you will quickly learn that I hate the word “shall” in all its forms and believe it should be eliminated from legal writing, as soon as possible. In this case, the court did not need to determine whether “may” or “shall” was the appropriate word 24 for the contract, as the case was decided on other grounds; however the court made it clear that such rectification was within its power. 3.4 Review questions Question 5 A common mistake occurs where: (a) The mistake is commonly made by inexperienced commercial parties (b) Both sides have made a mistake, but the mistakes are different (c) Both sides have made the same mistake (d) The mistake occurs in relation to common law, not statute law Answer: (c) Question 6 What happens in a common mistake situation, where one party has given a mistaken undertaking that the circumstances were true? (a) The courts can rectify the mistake in the contract (b) This is not a common mistake situation (c) The contract will be void under the doctrine of mistake (d) The party in error will have 120 days in which to rectify the error under the doctrine of rectification 25 Answer: (b) Question 7 What does the phrase nemo dat quod non habet mean? (a) (b) (c) (d) Nemo the clownfish should avoid bad habits The mistake should be rectified if not habitual The mistake if quoted must be corrected You cannot give what you do not have Answer: (d) 4.0 Mutual Mistake Finally, let’s consider the last of the examples given in the introduction to this topic: Kahlia is a champion ballroom dancer in both the modern and Latin styles. She owns a beautiful white flowing modern ballroom dress, and a very daring and racy white Latin dress. Antoinette approaches Kahlia, who was wearing the Latin dress, and says “I’d like to buy your white dress for $1200.” Kahlia is hard up the cash, so she agrees, thinking that Antoinette intended to buy the white dress Kahlia was wearing. In fact, however, Antoinette wished to buy the other white dress. In this case, both parties have made a mistake but they have made different mistakes. Kahlia believes Antoinette wants to buy the Latin dress. She is wrong. Antoinette believes Kahlia wants to sell the modern ballroom dress. She’s wrong. The law describes this situation as a mutual mistake. Read this next bit until your eyes bleed: if the parties make the same mistake, it is a common mistake. If the parties make different mistakes, it is a mutual mistake. 26 This simple distinction probably costs contract students more marks than any other single point of law made in either Contract A or Contract B. Trust me, I’m not kidding here. How on earth is the law going to settle a dispute under these circumstances? To do so, we return to our old friend the reasonable person, who exercises the objective test. We ask “would a reasonable person, observing the formation of this contract, consider one party to be right and the other party to be wrong?” So, in the circumstances given, if a third party was standing there when Antoinette asked to buy Kahlia’s dress, would that third party have had any reason to believe that the parties had agreed to sell either the Latin dress or the ballroom dress? If the reasonable person can identify that one party is right and the other party is wrong, then the matter will be treated as one of unilateral mistake, and the rules of unilateral mistake will apply. If, however, the reasonable person is unable to identify that one party is right and the other party is wrong, then it will be abundantly clear that the parties were never ad idem, so the contract will be void. The classic case on mutual mistake is Raffles v Wichelhaus [1864] 159 ER 375. In this case, two ships, both bearing the name Peerless, set out from Bombay within a few months of one another. The two parties undertook a contract for the delivery of goods via the ship Peerless. You guessed it: one party understood the contract to refer to the Peerless which left Bombay in October; the other party understood the contract to refer to the Peerless which left Bombay in December. Realistically, there was no way for a reasonable person to tell 27 which of the two contracting parties was right. It was not possible to say that one party was correct and the other had made a unilateral mistake. Under those circumstances, the only reasonable thing to do was declare the mistake to have been mutual and the contract to be void. 4.1 Review question Question 8 A mutual mistake is: (a) A mistake both parties have made together (b) A situation where each party has made a different mistake (c) A situation where a reasonable person would have made a mistake (d) A situation in which consideration has failed Answer: (b) 5.0 Review In this topic we have covered the three general categories of mistake: unilateral mistakes, where a mistake is made by one party only; common mistake, where both parties make the same mistake; and mutual mistakes, where each party makes a different mistake. 28 We have examined three different types of unilateral mistake: mistakes as to the nature of the subject matter, mistakes as to the identity of the other party, and mistakes as to the nature of the contractual document. While these mistakes are all unilateral in nature, they have very different applications for the outcome of each dispute. In each case, the court is required to balance the certainty which ought to be inherent in a signed contractual document, with the need to do justice where a signature may have been improperly procured. We have then considered common mistake, where both parties make the same mistake as to the existence of the subject matter or as to the title of the subject matter. In most cases, the result of such a mistake will be to void the contract, although equity law provides a range of alternative remedy. Finally, we have considered mutual mistake where each party makes a different mistake. If, after the application of an objective test, it truly is clear that each party has made a difference mistake, then it is impossible to say that the parties were ever ad idem. As a result, the contract is void. 6.0 Tutorial Problems Problem 1 Lord Mitchell of the Seven Golden Orbs Please watch the short animated video at the following link, and then consider the questions below. Apologies in advance to any 29 other fans of Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series … but I couldn’t help myself. May Mr Jordan rest in peace. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8PkukYiMzDk Is Mitchell’s mistake unilateral, common, or mutual? Which of the cases you have learned about this week most closely approximates Mitchell’s circumstances? What remedy does Mitchell have against the menswear store attendant who was posing as Jordan Roberts? [30 Minutes] 7.0 Debrief After completing this topic you should recognize: How to identify a unilateral mistake; How the rules in Taylor v Johnson apply to unilateral mistakes about subject matter; How unilateral mistakes are resolved if the parties were not face-to-face during contract negotiations; How unilateral mistakes result if the parties were face-toface during contractual negotiations; Those circumstances in which the court will set aside a contract in accordance with the doctrine non est factum, because the person who signed the document believed it to be of another type; 30 How to identify common mistake and how to distinguish between res extincta and res sua; The equitable remedies which may be available for common mistake; and How to identify a mutual mistake by applying the objective test. 31