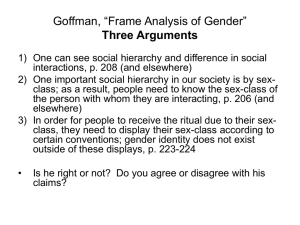

3. Distinguishing Hierarchy and Precedence: Comparing status

advertisement