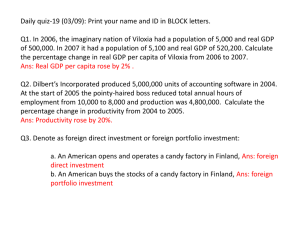

'Creative Destruction': Chinese GDP per capita from the Han

advertisement