A thick interpretation of the law finds that the rule of law is the core of

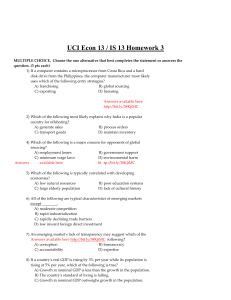

1.

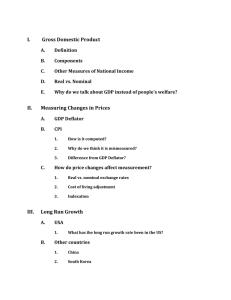

A thick interpretation of the law finds that the rule of law is the core of a just society. This concept is linked with liberty and democracy. In the thick interpretation, the rule of law must enforce political morality – such as freedom of speech and individual rights – in order to lead to development. In the this interpretation of the law – the law must do one thing: provide stability. To do this it must ensure property rights and the enforcement of justice, nothing more.

2.

Douglass North focuses on institutional law, which is most closely connected with thin law. It focuses on property rights, economic organization, transaction costs, and stability. To encourage high investment and to grow, laws must be predictable and stable.

3.

The rule of law was first brought to economists’ attention in the 1990s by the collapse of both post-Soviet economies and the fall of the currencies of the

Asian Tigers. They began to notice what laws worked for development and thought they could use them to explain the development of some countries versus the lack of development in others. With the collapse of the Asian

Tigers and Washington Consensus, the economists realized that their interpretation of correct laws was flawed. This led into the full examination of rule of law as integral to development.

4.

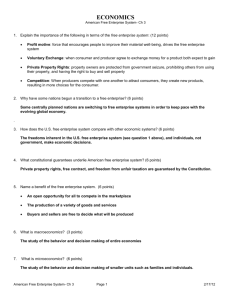

According to this graph, if t=your have a higher score on the rule of law scale, the nominal GDP per capita in your country is expected to increase. Nominal

GDP per capita is positively linearly correlated with rule of law, so if rule of law increases, so does nominal GDP per capita.

5.

China is growing in a way that is not consistent with the main points of the article at all. Though China does have well-established property rights, stable laws, and a decent thin level of law, it does not have much more. China is wrought with corruption and with laws that blatantly contradict the thick interpretation of laws. China has grown exponentially, but without the rule of law that this article considers.

6.

Equilibrium level of income – where y(G) = G(y) a.

y(G) = By G(y) = Ay^1/2 B = 1 A = 100 b.

By = Ay^1/2 c.

y = 100y^1/2 d.

y/y^1/2 = 100 e.

y^1/2 = 100 f.

(y^1/2)^2 = 100^2 g.

y = 10000

7.

relevant constant – constant in G(y) = A(1.1)y^1/2 y(G) = By a.

110y^1/2 = 1y b.

y/y^1/2 = 110 c.

y^1/2 = 110 d.

Y^(1/2) ^2 = 110^2 e.

Y = 12100

8.

(AX / Ay) = 2 and that country X is 20 years ahead technologically of Y and that technology grows at 1.1% a year. a.

Ax / Ay = (Tx/Ty)(Ex/Ey)

b.

Tx/Ty = (1+g)^-yearsbehind = (1+.011)^-20 = .8034 c.

Ex/Ey = (Ax/Ay) / (Tx/Ty) = 2/.8034 = 2.489

In this example, institutions clearly dominate technology, as institutions are what drives efficiency. In this example, institutions are over three times more important than technology when determining productivity differences between these two nations.