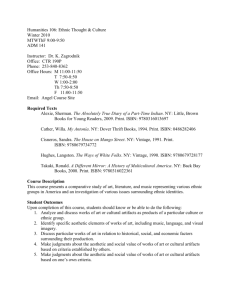

Takaki essay - White matters

advertisement

Takaki essay Responses to “other”: an essay on the development of a multicultural United States Diane Schmitz EDUC 591 Seattle University February 14, 2008 1 Takaki essay 2 Everybody remembers the first time they were taught that part of the human race was other. That‟s a trauma. It‟s as though I told you that your left hand is not part of your body (Toni Morrison as cited in Takaki, 1993, p.427). Analysis The creation and development of the United States is a story of trauma for multiple parts of its “body.” Throughout its history, multiple groups of people were identified as “other,” marked as different from the dominate group and its norms, and therefore, devalued, degraded, harmed and in some cases, nearly obliterated. This essay will demonstrate how the self/other binary leads to ideologies out of which systems are constructed that create patterns of oppression. Carr and Zanetti (1999) noted that binary thinking creates oppositions and hierarchy. “The existence of binaries suggests a struggle for predominance. One proposition must prevail, and the other must be vanquished” (p. 324). This dualistic Western thought led to ideologies such as demonization, colonialism, and assimilation in service of “progress.” They became embodied in the “loveliness of white” declared by Benjamin Franklin (Takaki, 1993, p. 79) as opposed to the savagery of those who were not white. These constructions led to the development of economic, political, religious and social systems which had interplay among them and patterns of oppression embedded within them. Much of what occurred can be traced back to a manifestation of the self/other split that resulted in an ideology of savagery. Takaki (1993) explained that the English, as part of their colonizing actions, had “developed an ideology of „savagery,‟ which was given form and content by the political and economic circumstances of the specific sites of colonization” (p. 44). The “other” was identified as savage and uncouth, many levels below the civilized white colonists and therefore not worthy of the same privileges. Sometimes the savagery was viewed as cultural (as in Ireland with the Irish and in Virginia with the Indians) and therefore the “other” could be educated out of their Takaki essay 3 ignorance to become similar to the English. However, the Indians in New England were demonized in racial ways that attributed their dark complexions to an inherent association with evil and the devil; a result of the religious fervor brought to New England by the colonists (Takaki, p. 44). These are examples of how projection plays out in binary thinking in racist ways. Gunaratnam and Lewis (2001) described how “processes of racialisation and racist beliefs are key schizoid mechanisms involving the splitting of negative and positive aspects of the self and/or „our‟ group and the projective identification of the negative aspects into the „other‟ or abjected group” (p.143). Tochluk (2008) claimed that the Indian way of being was not just “other,” it was wrong. “The correct way of being an American meant to take on the values of the white American self, a self that was independent and personally ambitious, and who accumulated wealth (p. 86). Dualistic body/mind framing also had an impact in colonial times. The Puritan belief in firm boundaries between the highly valued mind, and the devalued and suspect body, created anxiousness at their perceived lack of those boundaries by the Indians. Therefore, the Indians personified that fear within the Puritan society (Takaki, 1993, p. 40). The impact of such thinking was substantial as such “savages” needed to be controlled. The construction of the ideology of savagery was to “set a course for the making of a national identity in America for centuries to come” (Takaki, p. 44). English whiteness and its customs became the standard measurement of all that was good and holy. Irish immigrants were compared to apes and classified as a „race of savages‟ who pursued animal passions and had a low level of intelligence (Takaki, 1993, p. 149). Blacks were also associated with apes and the colonists projected on them the hidden and rejected instinctual parts of their own human nature (Takaki, p. 59). Justification for destruction of the Indian tribal Takaki essay 4 system was framed as getting rid of what was “perpetuating habits of nomadic barbarism and savagery” (Takaki, p. 235). Chinese immigrants were described as heathen, savage and lustful and assigned characteristics previously assigned to blacks (Takaki, p. 205). The common identity of savages attributed to blacks, Indians and Chinese became codified with a California Supreme Court decision in 1854 (People v. Hall) that concluded that none of them were allowed to testify against whites (Takaki, p. 206). The inferior Mexican race was to give way to the conquest by the superior white race and Mexican Americans were subject to the “Greaser Act” aimed at controlling their behavior (Takaki, pp. 176-178). In 1911, a Mexican American referred to “the magic that surrounds the word white” (Takaki, p. 190). That magic was assumed in the comments of a United States senator proudly extolling the destruction of savagery in the white migration westward that was advancing civilization (Takaki, p. 191). Such comments had inherent in them the idea of progress as defined by the dominant culture; the impact on the subordinate culture, if noticed at all, was seen as necessary for the “greater good.” Progress was another ideology that significantly impacted the development of the country. Andrew Jackson, while lamenting the impact of Indian removal and destruction, argued that such actions were a moral necessity to extend civilization across America (Takaki, 1993, p. 88). Competition over land led to the racialization of Indian savagery as the colonists insisted that entitlement to land brought with it the obligation to utilize it in certain ways, which in reality meant their ways. The progress enabled by the building of the railroads was a priority for modern America and the loss of land, buffalo, and a way of life for the Indians were necessary costs. “The march of empire no longer proceeds with stately, measure strides, but has the wings of morning, and flies with the speed of lightning” a newspaper proclaimed (Takaki, p.102). The Yankees extolled their own traits of industry and enterprise as distinguishing them from the lazy Takaki essay 5 Mexicans who spent too much time in pleasure-giving activities and too little developing the potential of their country (Takaki, p.171). Jefferson‟s vision of progress was to have the American continent be a uniform one with everyone speaking the same language and governed in similar ways (Takaki, p.166). “The doctrine of „manifest destiny‟ embraced a belief in American Anglo-Saxon superiority – the expansion of Jefferson‟s homogeneous republic and Franklin‟s America of „the lovely White.‟” (Takaki, p. 176). People who wanted to be part of such glorious progress were expected to assimilate into the values and norms of the white culture to enjoy all the promise that America offered. Nieto (2007) emphasized how dominant group members think of dominant cultural values as “normal” while assessing the values of subordinated groups as wrong (p. 172). Progress in these early days of the development of the United States was defined by the whites for the whites. However, whiteness alone was not always a guarantee of acceptance; social and economic class played a significant role in the integration or segregation of groups that became part of America. Class conflicts heated up as the expansiveness of the frontier came to an end near the turn of the 19th century and a multicultural America sought to define borders to keep in place racial and class hierarchies within a limited amount of land. Ownership of land and class were intimately related. However, class had been a factor in the United States since colonial times when most workers in Virginia were white indentured servants laboring along side African slaves in an environment of exploitation and abuse created by settlers from a background of English aristocracy (Takaki, p.55). Laws were passed that extended the time of indentured servitude for blacks and whites (often servitude for life for blacks), which reduced competition for land and maximized the supply of labor. This resulted in the creation of “what the planter elite fearfully called a „giddy multitude‟ – a discontented class of indentured servants, slaves, and Takaki essay 6 landless freemen, both white and black” (Takaki, p. 63). This was compounded by the Virginia legislature restricting voting rights to only the landowners in 1670 (Takaki, p. 63). Thus, the political realm of laws and voting privileges, the economic impact of restricted land ownership, high taxation, exploitation of labor, and deep seated prejudices and distrust of the “other” combined in an explosive way that erupted in Bacon‟s rebellion in 1676. The rebellion had its roots in a landholder, Nathaniel Bacon, who sought to organize the “giddy multitude” against the Indians as the enemy and also redirect their attention and anger from the elite (Takaki, 1993, 63). The other elite were alarmed at Bacon‟s organizing the “rabble crew” and after the killings of the Indians, charged him with treason. Bacon‟s response was to lead five hundred men, white and black, to Jamestown where they burned it to the ground. Eventually the rebellion was defeated but it gained a place in history as the largest rebellion in any American colony before the American Revolution (Takaki, p. 65). This event impacted landowners as they recognized that depending on white labor would always leave open the possibility of insurrection. They decided to “reorganize society on the basis of class and race” by a transitioning to a preference for black labor and a reduced recruitment of white indentured servants (Takaki, p. 65). This movement gained power from its timing in the late 1600s. The Virginia legislature continued to institutionalize slavery by enacting punishment of lifelong servitude, denying slaves the freedom of assembly and movement, defining a slave as property, defining who was “black,” prohibiting interracial unions and allowing white to physically abuse blacks (Takaki, pp. 65-67). This combination of oppression through economic, political and social control firmly put in place a caste system that solidified slavery. Throughout the history of the United States, the impact of class was substantial. The Mexican class system of landed elite was in place before the American conquest of California Takaki essay 7 and Texas; stratification began with the “people of reason” at the top and went down the ladder to the laboring class and down from there depending on the color of people‟s skin (Takaki, 1993, p. 169). When the Mexican government prohibited further American immigration into Texas, the Mexican elite were opposed to it as they saw their counterparts as industrious people bringing progress (Takaki, p. 173). That support was eroded later when political restrictions, enacted after the American conquest, taxed those elite to make them economically vulnerable and took away their rights as landowners (Takaki, p. 181). Once again, political and economic power combined to strengthen oppression. Immigrants to the United States faced these same forces. Between 1885 and 1924, Japanese immigrants came to the U.S. mainland (180,000) and Hawaii (200,000) because of economic hardships in Japan (Takaki, 1993). A significant number were utilized as field labor in Hawaii which did not have a large white working class; whites occupied skilled and supervisory positions. When the Japanese immigrants rebelled against working conditions by striking, Koreans and Filipinos were imported to make an “ethnically diverse labor force in order to create division among their workers and reinforce management control” (Takaki, p. 252). In 1919, the Japanese joined Filipino workers in a strike as unity in class trumped other differences. Jewish immigrants, escaping political and religious persecution in Russia and Eastern Europe in the 1880s, were educated but inadequately trained in a profession (Takaki, 1993, p. 282). Although some became peddlers, the majority worked in the garment industry and suffered in sweatshops (Takaki, p. 288). A strike in 1909 signified the labor unrest and set the stage for numerous strikes and organizational movements in the next ten years. In those earlier years a tragedy emphasized the conditions in which this laboring class worked. The Triangle Shirtwaist Takaki essay 8 Company fire in 1911 trapped 800 young women and 146 of them, mostly Jewish and Italian, died (Takaki, p. 289). The response to this and other experiences solidified a class and ethnic movement that led to labor triumphs. Five and a half million Irish immigrants came to America between 1815 and 1920 (Takaki, 1993, p. 140). They were driven from Ireland by English tyranny and economic hardship from the potato famine. The immigrants were poor, unskilled laborers pulled to America by the Market Revolution‟s demand for labor to construct roads, waterways and rail lines (Takaki, 1993). Irish women, mostly illiterate, entered domestic service and factory work. Although initially sympathetic to blacks from their experiences of being slaves to the British, the Irish immigrants moved into competition with blacks for employment. This led to many immigrants promoting their whiteness as “a powerful way to transform their own identity from „Irish‟ to „American‟ which included attacking the blacks in the same oppressive ways they had experienced the British” (Takaki, p. 151). This illustrates that oppression begets oppression, economic forces drive racial and class oppression, and that classification of the “other” has detrimental consequences. Mexican immigrants, migrating to the north between 1900 and 1930 to escape poverty and war, were from an agricultural laboring class and filled the need for workers on the railroads, in cotton and beet fields, hotels and construction (Takaki, 1993). A two-tiered labor market existed with the whites protecting the skilled level positions; in Los Angeles in 1918, 70% of the Chicanos were unskilled blue-collar workers (Takaki, p. 318). Chicana workers in factories, plants, and canneries “were usually assigned to the worst jobs and received the lowest wages” (Takaki, p. 319). “Chicano [agricultural] workers . . . found themselves in a labor market that had been deliberately oversupplied in order to force them to work from contract to contract for low Takaki essay 9 wages” (Takaki, p. 322) and “Chicano laborers were paid lower wages than white workers for the same type and amount of work” (Takaki, p. 323) while being shut out of more skilled jobs because they “weren‟t fitted” for that kind of work. The Chicanos resisted through labor struggles and strikes and employers evicted them from migrant camps saying “the Mexicans are trash; they have no standard of living” (Takaki, p. 325). Economic forces and political interests kept class firmly anchored in place. Chinese immigrants began arriving in the United States in 1849 fleeing from the combined forces of political and class persecution (the British opium wars) and harsh economic conditions (Takaki, 1993). Mostly men, many of the immigrants had little schooling and were initially welcomed as cheap labor working on the railroads, mines and in agriculture. As economic times grew hard, the Chinese became targets of white labor resentment which led to violence against them and caused the Chinese to move into urban centers, creating selfemployment in stores, restaurants and laundries. Arguments ensued within the upper class whites whether the Chinese should be a temporary labor force returning to China or a permanent supply of labor for the unwanted jobs in society; either way the upper class was invested in keeping the lower class positioned the same. What enabled businessmen . . . to degrade the Chinese into a subservient laboring caste was the dominant ideology that defined America as a racially homogeneous society and Americans as white. The status of racial inferiority assigned to the Chinese had been prefigured in the black and Indian past (Takaki, p. 204) Racial oppression, economic repression, and political oppression together solidified the class system for the Chinese as it had for many other groups in America, particularly the blacks. Early black history in America was framed through the lens of slavery but it is important Takaki essay 10 to recognize that the class origins of slavery were often hidden (Takaki, 1993, p. 61). Some of the ramifications of that were discussed earlier in this paper. Class continued to be part of the black experience in later years as well. Blacks migrating to the urban north in the early part of the 20th century constituted a major exodus from the south to cities like Detroit, Cleveland, Chicago and New York; this new generation of blacks born after slavery wanted change and the possibility of escaping caste (Takaki, p. 345). But, the substantial influx of blacks to Chicago ignited white resistance and once again, economic and political pressure through segregation in housing, schools and workplaces, worked to keep the blacks “in their place.” According to Takaki (1993), black workers were used as strikebreakers and then discharged, employed in lowwages jobs, were entrapped by poverty, and unemployed 30 to 60 percent more than whites. The Great Depression put blacks at more risk as blacks were “endeavoring to hold the line against advancing armies of white workers intent upon gaining and content to accept occupations which were once thought too menial for white hands” (Takaki, p. 367). As this history demonstrates, class and race are tightly bound to one another and strongly impacted by economic forces. In addition to economic forces, it is important to be aware of social, political, legal and religious forces that contributed to oppression and repression in the history of the United States. There is not space in this paper to address these in great detail, but some examples will illustrate the impact that they had on the country. Religious beliefs were one such force. Puritan religious values informed their responses to the “other.” The Christian tradition contributed to dualistic thinking with an emphasis on the struggle between a mortal, sinful body versus an immortal, holy soul (Grosz, 1994). An irrational fear, such as fear of the body, can create fear of the „other‟ – or fear of the „other‟ in the self (Gunaratnam & Lewis, 2001). Projection of this fear onto others (Indians, blacks, immigrants) was common by the Puritans as Takaki essay 11 part of the ideology of savagery as the “colonists feared the possibility of losing self-control over their passions” (Takaki, 1993, p.59). Christianity was viewed as the one true religion divinely sanctioned by a God who was pleased to “visit the Indians with a great sickness” (Takaki, 1993, p. 39), and who “pushed the Pequots into a „fiery oven‟ filling the place with dead bodies” (p. 42). Mexicans noted that Americans believed that “God made the world and them also, therefore what there is in the world belongs to them as sons of God” (Takaki, p. 172). John Winthrop, a leader in the colonies, explained how it was their God-given responsibility to transform the wilderness into civilization (Takaki, p. 42). This belief in a manifest destiny destroyed land and people and disregarded the spiritual beliefs of the native peoples. Assimilation was a strategy to have different cultures and ethnic groups conform to the dominant culture, which in the United States has been an Anglo-Saxon Protestant one. This was a method to “unify” the nation as expressed by Jefferson. It led to the development of Indian boarding schools where young children, taken from their parents, had their hair cut, their language forbidden, their clothes replaced with “American” ones, and were pressured to convert to Christianity, as they learned the American white way. This was a way to separate them from their cultural connections and resulted in years of social and emotional problems (Nieto, 2008, p. 183). Assimilation was also a strong factor in the Jewish experience in America. The Jewish immigrant went through a process of „purification‟ as they learned to wear proper clothes, speak good English, Americanize their names, participate in consumerism and celebrate American holidays (Takaki, 1993, p. 300). The media was a political force that fanned the flames of racism and strengthened the calls for manifest destiny in editorials, headlines and articles. “It is the duty of Uncle Sam to Takaki essay 12 remove the Pawnee population” asserted a Nebraskan paper (Takaki, 1993, p. 103), “Land should not be given to the freedmen” proclaimed the New York Times (Takaki, p. 133). “The North is becoming black with refuges Negroes from the South. These wretches crowd our cities, and by overstocking the market of labor, do incalculable injury to white hands” an Irish newspaper told its readers (Takaki, p. 152). A California newspaper threatened striking Chicanos: “Many of you don‟t know how the United States government can run a concentration camp” (Takaki, p. 325). Referring to the conquest of California as inevitable, an editor insisted, “There are some nations that have a doom upon them . . . the nation that makes no onward progress . . . that wastes its treasure wantonly. . . such a nation will become the easy prey of the more adventurous enemy” (Takaki, p. 177). Legalizing oppression through laws that supported the interests of whites was very common. Laws institutionalized slavery; immigration laws kept people out when they weren‟t wanted and let them in when they were. Laws separating race from religion were passed beginning in 1667 in Virginia; consequently “the distinction was no longer between Christianity and heathenism or freedom and slavery, but between white and black” (Takaki, 1993, p. 59). Reproductive repression was legalized with laws that forbid sexual relations and marriages between different races such as the 1880 law prohibiting marriage between a white and Negro, Mulatto or Mongolian (Takaki, p. 205). Voting rights were an important part of the political process, however, “the political proscription of blacks often accompanied the advance of democracy for whites” (Takaki, p. 108). In 1821, suffrage for free white males was granted but blacks were required to be property owners in order to vote. Treaties with the Indians were made and broken time after time in efforts to accumulate more land for the whites and the expansion of the country. An 1830 law provided for Indian removal through land allotment policies and Takaki essay 13 treaties (Takaki, p. 88). The Naturalization Act of 1790 ensured that non-whites would be excluded from citizenship which covered not only the nonwhite immigrants but the Indians already living in the land (Takaki, p.80). The Dawes Act in 1887, described at the “Indian Emancipation Act” sought to break up the reservations by making the Indians individual property owners (Takaki, p. 234) resulting in one-seventh of Indian lands being gone by 1891. “Legislation which granted railroad corporations right-of-way through Indian lands coincided with the enactment of the Dawes law: in 1886-87, Congress made six land grants to railroad interests” (Takaki, p.236). In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act prohibited immigration and was fed by fears that white workers were being hindered (Takaki, p. 207). “Proclaiming the doctrine of separate but equal in the 1896 ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of segregation” (Takaki, p. 138). Another factor in the history of the multicultural United States was the impact of WWII as it redefined the American mission as democratic and antiracist in opposition to the genocide of Jews by Hitler (Takaki, 1993, p. 375. The war united the different cultural groups again a common enemy although several of them noted the irony of fighting for freedom they didn‟t have in their own country or supporting a country that had robbed them of their land. One significant impact was the increased visibility of racism and segregation in the armed forces and defense industries which led to a March on Washington and Roosevelt authorizing the Committee on Fair Employment Practices in 1941 (Takaki, p. 397). World War II raised the demands for racial equity in the United States and it became the bridge to the Civil Rights Movement. The Civil Rights Movement, in the 1950s and 1960s, raised awareness through the Montgomery bus boycotts, the Woolworth sit-ins in North Carolina, the freedom rides and the Takaki essay 14 March on Washington in 1963 as Martin Luther King, Jr. proclaimed his dream for all Americans. “The Civil Rights Revolution, however, was unable to correct the structural economic foundations of racial inequality. While the laws and court orders prohibited discrimination, they failed to abolish poverty among blacks” (Takaki, p. 409). The 1954 Brown v Board of Education decision made segregated schools unconstitutional, “but integration remained largely a court ruling on paper, while segregation persisted as a reality in society” (Takaki, p. 402). Today, despite court rulings, and changes on other fronts, fear and judgment of the “other” remains a controlling force as white power and privilege continues to be dominant and true integration remains an ideal. To think the ideology of savagery has gone by the wayside is to be ignorant. Last September, a Michigan State University student hate group criticized the university‟s decision to establish a Chicano/Latino Studies doctoral program by putting out a news release with the headline, “MSU Offers Doctorate in Savagery” (Holthouse, 2007). If the thesis of this paper has merit, then addressing the self/other split is an important vehicle for making progress towards a healthy and respecting multicultural America. Hobgood (2007) asserts an intriguing thesis that racism is perpetuated by a projection of white self-alienation (p. 43). Racism gives those constructed as white a set of comforting identities, often at odds with their actual social reality . . racism provides scapegoats for angry, frustrated whites who remain mystified as to the real source of their problems (p. 44). Tochluk (2008) advocates for a witnessing whiteness culture to bring about transformation. What we need to transform is the white culture people speak of that is associated with segregated social lives, isolation, disconnection, individualism, sanitization, arrogance, Takaki essay 15 obliviousness, entitlement, unrecognized privileges, the avoidance of social concerns faced by disproportionate numbers of people of color, the sense of self as normal, innocent, and unaffected by race, and the acceptance of Western ideals as universal and the only valid way of seeing the world (p. 300). Perhaps the title of a newly published book says it best: “Interrupting White Privilege. . . Break the Silence” (Cassidy & Mikulich, 2007). Personal Reactions The majority of this information was new to me; a dreadful indictment of the schooling I received growing up in middle class, homogeneous Spokane, Washington, attending college in the same area, and in my master‟s degree program at this university. The information with which I was familiar has primarily come to me in the last 10 years through my own selfeducation, my doctoral degree program, and my co-workers at Seattle University. It is the expansion of my circle of friends and co-workers into a more multicultural and multiracial group that has made the most impact. Most importantly, I have become much more aware of my own power and privilege as a white, heterosexual person and it changes how I look at everything. As a woman, I‟ve had multiple experiences of oppression throughout my life. I‟ve understood what it is to be in the subordinate group and sympathized with others who experienced that. Yet, I‟m also white, middle class, and heterosexual and much of my life has been lived with an experience of being in the dominant group. When I reflect on my own pre-college education, I remember noticing the black student in our middle school; he was the first black person I remember meeting. I was white in a sea of whiteness. Students, teachers, administrators were white or taken by me to be white. I never thought about whiteness because I was part of the “norm” and never had to consider it. I was in Takaki essay 16 high school during the civil rights movement and recognized its importance but it still felt distant; my life went on the way it always had, a result of unearned privilege. In earlier schooling, I had learned the stories of the great explorer Columbus, the friendly Indians who we helped us, the bad Indians that needed to be punished, our exemplary founding fathers, our expansion westward into the great frontier, our amazing inventions and how great was our country. The “our” and “we” and “us” of course meant “white.” It never occurred to me to question this domination. Loewen (1995) emphasized that if domination is never questioned in school, then the assumption is that it was just a natural outcome. “Since textbooks don‟t identify or encourage us to think about real causes, „we‟re smarter‟ festers as a possibility (p. 35). I knew there was some slavery and conflicting opinions about some issues, but most of it was minimized in my social studies classes by an unspoken agreement that white was right. I grew up confident of my identity as a valued person and part of an ideal history of which I was taught to be proud.. If I had been part of a minority, my story would have been different. If I had grown up with a curriculum that didn‟t reflect my race, ethnicity or religion or reflected it only in a negative way, I would have internalized that as shame and indication that I was of little value. “Young people whose languages and cultures differ from the dominant group often struggle to form and sustain a clear image of themselves” (Nieto, 2008, p. 170). I was surprised that the Takaki book made no mention of GLBT discrimination or the misogyny directed at women throughout American history as such acknowledgement and lack of representation has impacted the health and welfare of many in those groups. There is no doubt in my mind that Takaki‟s history was not taught because it did not reflect well on the dominant culture; the people in power are the ones who write the history books. Although some argue that including too much of a shameful past can be destructive, I Takaki essay 17 agree with Tochluk (2008) when she says, “we would do well to admit that this orientation largely serves white folks by allowing us to retain a sense of self as coming from a positive and heroic history (p. 74). Despair is the feeling that I most often experienced while reading Takaki and the detail about the trauma that was inflicted on human beings in our country‟s development. Although, I‟d like to be optimistic, the current state of affairs in our country does not take me there. Over the weeks we‟ve been in class, I‟ve read articles in the local paper about the Korean college student called Asian slurs and beaten, the racial gaps in prosecution of marijuana charges, the scheduling of a county democratic convention on the first day of Passover, a report from Chicago showing that minorities are less likely to get prescribed strong narcotics by emergency room doctors, a Seattle schools consultant report detailing “a tale of two districts” noting the disparities among student-income levels, an article detailing botched accounting by federal bureaucrats managing Indian trust accounts, the significant increase in malicious harassment of gay men on Capitol Hill, stories about the painful legacy of Indian boarding schools, and the one about the last fullblooded Eyak Indian dying, and with her, the last person fluent in her Native language. My hope is that we will come to honestly answer Langston Hughes‟ question, “What happens to a dream deferred?” (cited in Takaki, 1993, p.422) and with the hard answers to that question, be compelled to make a change. Such change requires an authentic commitment to action to ensure the dreams of all Americans are equally honored and supported by doing the hard work to dismantle white privilege and other systems of oppression. “Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed” (Langston Hughes cited in Takaki, p. 425). Takaki essay 18 References Carr, A. & Zanetti, L.A. (1999). Metatheorizing the dialectic of self and other. American Behavioral Scientist, 43(2). 324-345. Cassiday, L.M. & Mikulich, A. (Eds.). (2007). Interrupting white privilege: Catholic theologians break the silence. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. Gunaratnam, Y. & Lewis, G. (2001). Racialising emotional labour and emotionalizing racialised labour: anger, fear and shame in social welfare. Journal of Social Work Practice, 15(2). 131-148. Grosz, E. (1994). Volatile bodies: Toward a corporeal feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Hobgood, M.E. (2007). White economic and erotic disempowerment: A theological exploration in the struggle against racism. In L.M. Cassidy & A. Mikulich (Eds.) Interrupting white privilege: Catholic theologians break the silence (40-55). Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. Holthouse, D. (2007). Black hats on campus. Intelligence Report. 128. 26-31. Loewen, J.W. (1995). Lies my teacher told me: Everything your American history textbook got wrong. New York: The New Press. Nieto, S. & Bode, P. (2008). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education (5th ed.). Boston: Pearson and Allyn Bacon. Takaki, R. (1993). A different mirror: A history of multicultural America. New York: Back Bay Books. Tochluk, S. (2008). Witnessing whiteness. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education.