Psychology, Second Edition

Copyright © 1986, 1989 by Worth Publishers, Inc.

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 88-50722

ISBN: 0-87901-400-8

4 5 - 93 92 91 90 89

Editors: Anne Vinnicombe and Deborah Posner

Production: Barbara Anne Seixas

Design: Malcolm Grear Designers

Art director: George Touloumes

Layout design: Patricia Lawson and David Lopez

Illustrators: Warren Budd and Demetrios Zangos

Picture editors: Elaine Bernstein and David Hinchman

Cover design: Demetrios Zangos

Composition: York Graphic Services, Inc.

Printing and binding: R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company

Illustration credits begin on page IC-1, and constitute an extension of the

copyright page.

Worth Publishers, Inc.

33 Irving Place

New York, New York 10003

Preface

My goals in writing this book can be reduced to one overriding aim: to

merge rigorous science with a broad human perspective in a book that engages

both the mind and the heart. I wanted to set forth clearly the principles

and processes of psychology and at the same time to remain sensitive

to students' interests and to their futures as individuals. My aim was a

book that helps students to gain insight into the phenomena of their

everyday lives, to feel a sense of wonder about seemingly ordinary

human processes, and to see how psychology addresses deep intellec­

tual issues that cross disciplines. I also wanted to produce a book that

conveys to its readers the inquisitive, compassionate, and sometimes

playful spirit in which psychology can be approached. Believing with

Thoreau that "Anything living is easily and naturally expressed in pop­

ular language," I sought to communicate scholarship with crisp narra­

tive and vivid story telling.

To achieve these goals, I established, and have steadfastly tried to

follow, eight principles:

1. To exemplify the process of inquiry. The student is repeatedly

shown not just the outcome of research, but how the research

process works. Throughout, the book tries to excite the read­

er's curiosity. It invites readers to imagine themselves as par­

ticipants in classic experiments. Several chapters introduce re­

search stories as mysteries that are progressively unraveled as

one clue after another is put into place.

2. To teach critical thinking. By presenting research as intellectual

detective work, I have tried to exemplify an inquiring, analyti­

cal mind set. The reader will discover how an empirical ap­

proach can help evaluate competing ideas and claims for

highly publicized phenomena ranging from subliminal persua­

sion, ESP, and mother-infant bonding to astrology, basketball

streak shooting, and hypnotic age regression. And whether

they are studying memory, cognition, or statistics, students

learn principles of critical reasoning.

3. To put facts in the service of concepts. My intention has been not

to fill students' intellectual file drawers with facts but to reveal

psychology's major concepts. In each chapter I have placed the

greater emphasis on the concepts that students should carry

with them long after they have forgotten the details of what

they have read.

4. To be as up-to-date as possible. Few things dampen students'

interest as quickly as the sense that they are reading stale

news. While doing justice to the classic contributions of prior

years, I therefore sought to present the most important recent

xii

Preface

developments in the discipline. Accordingly, 73 percent of the

references in this edition are from the 1980s, and 47 percent of

these were published between 1986 and 1989.

5.

To integrate principles and applications. Throughout—by means

of anecdotes, case histories, and the posing of hypothetical

situations—I have tried to relate the findings of basic research

to their applications and implications. Where psychology can

illuminate pressing human issues—be they racism and sexism,

health and happiness, or violence and war—I have not hesi­

tated to shine its light.

6.

To enhance comprehension by providing continuity.

Many chap­

ters have a significant issue or theme that links the subtopics,

forming a thread through the chapter. The "Learning" chap­

ter, for example, conveys the idea that bold thinkers (Pavlov,

Skinner, Bandura) can serve as intellectual pioneers. The

"Thinking and Language" chapter raises the issue of human

rationality and irrationality. Other threads, such as the naturenurture issue, weave throughout the whole book.

7.

To reinforce learning at every step. Everyday examples and rhe­

torical questions encourage students to process the material

actively. Concepts are frequently applied and reinforced in

later chapters. Pedagogical aids in the margins augment learn­

ing without diluting or interrupting the text narrative. Each

chapter concludes with a narrative summary, a glossary of de­

fined key terms, and suggested readings that are attuned to

students' interests and abilities.

8.

To provide organizational flexibility. I have chosen an organiza­

tion in which developmental psychology is covered early be­

cause students usually find the material of particular interest

and because it introduces themes and concepts that are used

later in the text. Nevertheless, many instructors will have their

own preferred sequence. Thus the chapters were written to

anticipate other approaches to organizing the introductory

course. Statistics, for example, is covered in an appendix, thus

facilitating its being covered at any time.

S E C O N D EDITION FEATURES

This new edition retains the first edition's basic organization, format,

and voice. It is, however, thoroughly updated (more than 40 percent

of the references are new to this edition), painstakingly revised and

polished paragraph by paragraph, and there are dozens of fresh

examples. Without watering down the content, new learning aids

summarize or diagram difficult concepts. Research related to biopsychology, gender, and industrial/organizational psychology is inte­

grated throughout the text, with a cross-reference guide to these topics

at the ends of the chapters on biological foundations, gender, and

motivation.

There are numerous changes within chapters:

To increase the appeal of biological psychology, Chapter 2—formerly the longest and most arduous chapter—has been shortened

by moving material on evolution and behavior genetics to later chap­

ters. Without reducing overall coverage of biological foundations, this

reduces redundant coverage and enables students to get more quickly

to inherently interesting neuroscience research.

Chapter 3 treats infancy and childhood within a single section,

lending more coherence to its coverage of physical, cognitive, and so­

cial development. Chapter 4 similarly unifies the coverage of adult­

hood and aging. Now, for example, we explore changes in memory,

intelligence, and other traits across all of the adult years.

Chapter 5, Gender, is reorganized, and now emphasizes more

strongly the social construction of gender.

Among the major changes in other chapters you will find new

material on the biology of memory, on the biological and cognitive

underpinnings of depression, on teen sexual activity and pregnancy,

on the psychological effects of AIDS, on well-being across the life span,

on drugs and behavior, and on managerial motivation. Coverage of

obesity has been moved to the chapter on health, pain to the chapter

on sensation, and the ethics of animal research are now discussed in

the introductory chapter. The discussion of TV, pornography, and ag­

gression has been carefully revised and updated.

SUPPLEMENTS

Psychology is accompanied by a comprehensive and widely acclaimed

teaching and learning package. For students, there is a successful

study guide, Discovering Psychology, prepared by Richard Straub

(University of Michigan, Dearborn). Using the SQ3R (study, question,

read, recite, review) method, each chapter contains overviews, guided

study and review questions, and progress tests. In this new edition,

all answers to test questions are explained and page-referenced—

enabling students to know why each possible answer is right or wrong.

Discovering Psychology is available as a paperback and Diskcovering

Psychology is a microcomputer version for use on IBM PC, Macintosh,

or Apple II.

The masterfully improved computer software prepared by Thomas

Ludwig (Hope College) brings some of psychology's concepts and

methods to life. PsychSim II: Computer Simulations in Psychology

contains eleven revised programs and five new ones for use on the IBM

PC or true compatibles, Macintosh, and the Apple II family. Some

simulations engage the student as experimenter, by conditioning a rat

or electrically probing the hypothalamus. Others engage the student

as subject, as when responding to tests of memory or visual illusions.

Still others provide a dynamic tutorial/demonstration of, for example,

hemispheric processing or cognitive development principles. Student

worksheets are provided.

The Instructor's Resources, created by Martin Bolt (Calvin College),

have been acclaimed by users everywhere. The resources include ideas

for organizing the course, chapter objectives, lecture/discussion topics,

classroom exercises, student projects, film suggestions, and ready-touse handouts for student participation. The new resources package is

30 percent bigger, now includes approximately 140 transparencies, and

offers many new demonstration handouts.

The Test Bank, by John Brink (Calvin College), builds upon the

first edition Test Bank, which was written and edited by Brink with the

able assistance of Martin Bolt, Nancy Campbell-Goymer (BirminghamSouthern College), James Eison (Southeast Missouri State University),

and Anne Nowlin (Roane State Community College). The new edition

includes definitional/factual questions, more conceptual questions

than previous versions, and adds a new section of essay questions. All

questions are keyed to learning objectives and are page-referenced to

xiv

Preface

the textbook. The Test Bank questions are available on Computest, a

user-friendly computerized test-generation system for IBM PC, Macin­

tosh, and the Apple II family of microcomputers.

IN APPRECIATION

Aided by nearly 150 consultants and reviewers over the last six years,

this has become a far better, more accurate book than one author alone

(this author, at least) could have written. It gives me pleasure, there­

fore, to thank, and to exonerate from blame, the esteemed colleagues

who contributed criticisms, corrections, and creative ideas.

This new edition benefited from careful reviews at several stages.

Nearly a thousand students at seven colleges and universities critiqued

the first edition. Fourteen sensitive and knowledgeable teachers of­

fered their page-by-page critique of the first edition after using it in

class. This resulted in hundreds of small and large improvements, for

which I am indebted to:

Lisa J. Bishop, Indiana State

University

Laurie Braidwood, Indiana State

University

William Buskist, Auburn

University

Thomas H. Carr, Michigan State

University-East Lansing

Richard N. Ek, Corning

Community College

Roberta A. Eveslage, ]ohnson

County Community College

Larry Gregory, New Mexico State

University

Michael McCall, Monroe

Community College-Rochester

James A. Polyson, University of

Richmond

Donis Price, Mesa Community

College

Walter Swap, Tufts University

Linda L. Walsh, University of

Northern Iowa

Rita Wicks-Nelson, West Virginia

Institute of Technology

Mary Lou Zanich, Indiana

University of Pennsylvania

Additional reviewers critiqued individual first edition chapters

and/or successive second edition drafts. For their generous help and

countless good ideas, I thank:

David Barkmeier, Bunker Hill

Community College

John B. Best, Eastern Illinois

University

Martin Bolt, Calvin College

Richard Bowen, Loyola University

of Chicago

Kenneth S. Bowers, University of

Waterloo

David W. Brokaw, Azusa Pacific

University

Freda Rebelsky Camp,

Boston

University

Linda Camras, DcPaul University

Bernardo J. Carducci, Indiana

University Southeast-New Albany

Dennis Clare, College of San Mateo

Timothy DeVoogd, Cornell

University

Alice A. Eagly, Purdue University

Mary Frances Farkas, Lansing

Community College

Larry Gregory, New Mexico State

University

Richard A. Griggs, University of

Florida-Gainesville

Joseph H. Grosslight, Florida State

University-Tallahassee

Diane F. Halpern, California State

University-San Bernardino

Janet Shibley Hyde,

University of

Wisconsin-Madison

Mary Jasnoski, George Washington

University

Carl Merle Johnson,

Central

Michigan University

John Kounios, Tufts University

Robert M. Levy, Indiana State

University

T. C. Lewandowski, Delaware

County College

A. W. Logue, State University of

New York-Stony Brook

Nancy Maloney,

Vancouver

William Siegfried,

John Simpson,

Donald H. McBurney,

Shelly E. Taylor,

University

University of

North Carolina-Charlotte

Community College-hangar a Campus

Matthew Margres, Saginaw Valley

State University

University of

Washington-Seattle

University of

California-Los Angeles

of Pittsburgh

Donna Wood McCarty, Clayton

Ross A. Thompson,

State College

Mark McDaniel,

Nebraska-Lincoln

Purdue University

Elizabeth C. McDonel,

University

of Alabama-Tuscaloosa

Douglas Mook,

University of

Virginia

James A. Polyson,

University of

Janet J. Turnage,

University of

University of

Central Florida

Ko Vandonselaar, University of

Saskatchewan

Nancy J. Vye, Vanderbilt University

Mary Roth Walsh,

University of

Richmond

Oakley Ray, Vanderbilt University

Lowell

Duane M. Rumbaugh,

Florida

Rita Wicks-Nelson, West Virginia

Institute of Technology

Georgia

State University

Neil Salkind, University of Kansas

Nancy L. Segal,

Wilse B. Webb,

University of

University of

Minnesota

In preparing the first edition, consultants helped me reflect the

most current thinking in their specialties, and expert reviewers

critiqued the various chapter drafts. Because the result of their guid­

ance is carried forward into this new edition, I remain indebted to:

T. John Akamatsu, Kent State

University

Harry H. Avis, Sierra College

Richard B. Day,

University

McMaster

Edward L. Deci,

University of

Bernard J. Baars, The Wright

Rochester

Institute

John K. Bare, Carleton College

Timothy DeVoogd,

Jonathan Baron,

University of

Pennsylvania

Andrew Baum, Uniformed Services

University of the Health Sciences

Cornell

University

David Foulkes, Georgia Mental

Health Institute and Emory University

Larry H. Fujinaka,

Leeward

Community College

Kathleen Stassen Berger, Bronx

Robert J. Gatchel,

Community College, City University of

New York

Allen E. Bergin, Brigham Young

University

Texas Southwestern Medical CenterDallas

Mary Gauvain, Oregon State

University

George D. Bishop,

University of

Alan G. Glaros,

University of

University of

Texas-San Antonio

Missouri-Kansas City

Douglas W. Bloomquist,

Judith P. Goggin,

Framingham State College

Texas-El Paso

Kenneth S. Bowers,

Marvin R. Goldfried,

University of

State

University of New York-Stony Brook

Waterloo

Robert M. Boynton,

University of

California-San Diego

Ross Buck,

University of

University of

Connecticut

Timothy P. Carmody,

San

Francisco Veterans Administration

Medical Center

Stanley Coren, University of British

Columbia

Donald Cronkite, Hope College

Peter W. Culicover, The Ohio State

University

William T. Greenough,

University

of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Joseph H. Grosslight, Florida State

University-Tallahassee

James V. Hinrichs,

University of

Iowa

Douglas Hintzman,

University of

Oregon

Nils Hovik, Lehigh County

Community College

I. M. Hulicka, State University

College-Buffalo

xvi

Preface

Janet Shibley Hyde,

University of

Wisconsin-Madison

Carroll E. Izard,

University of

Delaware

John Jung, California State

University-Long Beach

John F. Kihlstrom,

University of

Arizona

Kathleen Kowal,

University of

Alexander J. Rosen,

University of

Illinois at Chicago Circle

Kay F. Schaffer, University of

Toledo

Alexander W. Siegel, University of

Houston

Ronald K. Siegel,

School of

Medicine at the University of

California-Los Angeles

North Carolina-Wilmington

Donald P. Spence,

Richard E. Mayer,

Medicine at Rutgers The State

University of New Jersey

University of

California-Santa Barbara

Donald H. McBurney,

University

Richard A. Steffy,

Vanderbilt

Waterloo

Leonard Stern, Eastern Washington

University

University

Robert J. Sternberg,

of Pittsburgh

Timothy P. McNamara,

University

Donald Meichenbaum,

School of

of Waterloo

University of

Yale

University

Donald H. Mershon,

North

Carolina State University

Carol A. Nowak,

Center for the

Study of Aging, State University of

New York-Buffalo

Anne Nowlin, Roane State

Community College

Jacob L. Orlofsky,

University of

Missouri-St. Louis

Willis F. Overton,

Temple

George C. Stone,

Richard D. Walk,

Florida

Joseph J. Palladino,

Merold Westphal,

University of

Ovide F. Pomerleau,

School of

Medicine at the University of MichiganAnn Arbor

Dennis R. Proffitt,

University of

Virginia

Judith Rodin, Yale University

George

Washington University

George Weaver, Florida State

University

University

Daniel J. Ozer, Boston University

Southern Indiana

Herbert L. Petri, Towson State

University

Robert Plutchik, Albert Einstein

College of Medicine

University of

California-San Francisco

Elliot Tanis, Hope College

Don Tucker, University of Oregon

Rhoda K. Unger, Montclair State

College

Wilse B. Webb,

University of

Fordham

University

David A. Wilder,

Rutgers The

State University of New Jersey

Joan Wilterdink,

University of

Wisconsin-Madison

Jeffrey J. Wine, Stanford University

Joseph Wolpe, The Medical College

of Pennsylvania, Eastern Pennsylvania

Psychiatric Institute

Gordon Wood, Michigan State

University

Fourteen individuals read the whole first edition manuscript and

provided me not only with a critique of each chapter but also with their

sense of the style and balance of the whole book. For their advice and

warm encouragement, I am grateful to:

John B. Best, Eastern Illinois

University

Martin Bolt, Calvin College

Cynthia J. Brandau, Belleville Area

College

Sharon S. Brehm,

University of

Kansas

Steven L. Buck,

University of

Washington

James Eison, Southeast Missouri

State University

Robert M. Levy, Indiana State

University

G. William Lucker,

University of

Texas-El Paso

Angela P. McGlynn,

Mercer

County Community College

Carol Myers, Holland, Michigan

Bobby J. Poe, Belleville Area

College

Catherine A. Riordan,

University

of Missouri-Rolla

Richard Straub,

University of

Michigan-Dearborn

Robert B. Wallace,

Hartford

University of

Preface

Through both editions, I have benefited from the meticulous cri­

tique, probing questions, and constant encouragement of Charles

Brewer (Furman University).

At Worth Publishers—a company whose entire staff is devoted to

the highest quality in everything they do—a host of people played key

supportive roles. Alison Meersschaert commissioned this book, envi­

sioned its goals and a process to fulfill them, and nurtured the book

nearly to the end of the draft first edition. I am also indebted to Manag­

ing Editor Anne Vinnicombe, leader of a dedicated editorial team, for

her prodigious effort in bringing both editions to fulfillment and metic­

ulously scrutinizing the accuracy, logical flow, and clarity of every

page. For this edition, developmental editor Barbara Brooks's careful

analysis and thoughtful suggestions improved every chapter. Debbie

Posner demonstrated exceptional commitment and competence in co­

ordinating the transformation of manuscript into book, as did Chris­

tine Brune, who supervised countless editorial details. Thanks also go

to Worth's production team, led by George Touloumes, for once again

crafting a final product that exceeds my expectations.

At Hope College, the supporting team members for this edition

included Julia Zuwerink, Wendy Braje, and Richard Burtt, who re­

searched, checked, and proofed countless items; Kathy Adamski, who

typed hundreds of dictated letters without ever losing her good cheer;

Phyllis and Richard Vandervelde, who processed thousands of pages

of various chapter drafts with their customary excellence; and my psy­

chology colleagues, Les Beach, Jane Dickie, Charles Green, Thomas

Ludwig, James Motiff, Patricia Roehling, John Shaughnessy, and Phil­

lip Van Eyl, whose knowledge and personal libraries I have tapped on

hundreds of occasions. The influence of my writing coach, poet-essay­

ist Jack Ridl, continues to be evident in the voice you will be hearing in

the pages that follow.

XVI

Contents in Brief

PART

1

PART

Foundations of Psychology

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

2

2

CHAPTER

24

CHAPTER

PART

3

CHAPTER

6

CHAPTER

5

88

16

CHAPTER

3

CHAPTER

474

18

Health

Experiencing the World

506

136

6

Sensation

PART

138

7

Social Behavior

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

19

168

Social Influence

8

CHAPTER

States of C o n s c i o u s n e s s

PART

192

4

254

610

G-1

REFERENCES

R-0

ILLUSTRATION

CREDITS

NAME

NI-0

INDEX

SUBJECT

INDEX

IC-1

SI—1

11

Thinking and L a n g u a g e

CHAPTER

574

Statistical Reasoning in Everyday Life

GLOSSARY

228

10

Memory

CHAPTER

20

Social Relations

226

9

Learning

CHAPTER

546

APPENDIX

Learning and Thinking

CHAPTER

544

7

Perception

CHAPTER

442

17

Therapy

CHAPTER

PART

408

Psychological Disorders

116

406

15

Personality

4

Gender

380

Personality, Disorder, and Weil-Being

54

56

Adolescence and Adulthood

CHAPTER

14

CHAPTER

The Developing Child

348

Emotion

2

Development over the Life Span

346

13

Motivation

Biological R o o t s of B e h a v i o r

PART

5

Motivation and Emotion

1

Introducing P s y c h o l o g y

CHAPTER

xxviii

282

12

Intelligence

314

xix

Contents

PART

2

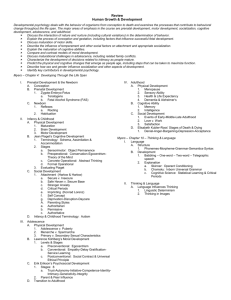

Development over the Life Span

CHAPTER

3

The Developing Child

DEVELOPMENTAL

ISSUES 57

Genes or Experience? 58

Stages? 58

Continuity or

Stability or Change? 59

PRENATAL

DEVELOPMENT

NEWBORN

59

From Life Comes Life 59

AND

THE

The Competent

Newborn 61

INFANCY

AND

CHILDHOOD

Physical Development 62

Development 65

Box

62

Cognitive

Social Development 70

Father Care 73

REFLECTIONS

ON

ISSUE:

AND

GENES

Temperament 80

A

DEVELOPMENTAL

EXPERIENCE

Studies of Twins 81

80

xxii

Contents

Adoption Studies 83 How Much Credit (or

Blame) Do Parents Deserve? 84

Summing Up 85 Terms and Concepts to

Remember 86 For Further Reading 87

CHAPTER

4

Adolescence and Adulthood

ADOLESCENCE

Physical Development 90

Development 91

ADULTHOOD

AND

Development 102

ISSUES

Cognitive

Social Development 95

AGING

Physical Development 98

REFLECTIONS

88

89

98

Cognitive

Social Development 104

ON

DEVELOPMENTAL

111

Continuity and Stages 111

Change 112

Stability and

Summing Up 114 Terms and Concepts to

Remember 115 For Further Reading 115

CHAPTER

5

Gender

116

BIOLOGICAL

GENDER: IS

INFLUENCES ON

BIOLOGY DESTINY?

118

Hormones 118 Sociobiology: Doing What

Comes Naturally? 119

THE SOCIAL

GENDER

121

CONSTRUCTION

Theories of Gender-Typing 121

Roles 124

GENDER

OF

Gender

Nature-Nurture Interaction 128

DIFFERENCES

128

The Politics of Studying Gender

Differences 129

How Do Males and Females

Differ? 129

Summing Up 134 Terms and Concepts to

Remember 134 For Further Reading 135

The Developing Child

In mid-1978, the newest astonishment in medicine, covering all the front

pages, was the birth of an English baby nine months after conception in a

dish. The older surprise, which should still be fazing us all, is that a soli­

tary sperm and a single egg can fuse and become a human being under

any circumstance, and that, however implanted, [this multiplied] cell af­

fixed to the uterine wall will grow and differentiate into eight pounds of

baby; this has been going on under our eyes for so long a time that we've

gotten used to it; hence the outcries of amazement at this really minor

technical modification of the general procedure—nothing much, really,

beyond relocating the beginning of the process from the fallopian tube to a

plastic container.

Lewis Thomas,

The Medusa and Snail, 1979

The developing child is no less a wonder after birth than in the

womb. As we journey through life from womb to tomb, when and how

do we change?

As psychologists Clyde Kluckhohn and Henry Murray (1956)

noted, each person develops in certain respects like all other persons,

like some other persons, and like no other persons. Usually, our atten­

tion is drawn to the ways in which we are unique. But to developmen­

tal psychologists our commonalities are as important as our unique­

nesses. Virtually all of us—Michelangelo, Queen Elizabeth, Martin

Luther King, Jr., you, and I—began walking around age 1, talking by

age 2, and as children we engaged in social play in preparation for life's

serious work. We all smile and cry, love and hate, and occasionally

ponder the fact that someday we will die. As preparation for consider­

ing both the similarities and differences in our physical, cognitive, and

social development, let us first confront three overriding developmen­

tal issues.

DEVELOPMENTAL I S S U E S

Three major issues pervade developmental psychology:

1. How much is our development influenced by our genetic in­

heritance and how much by our experience?

2. Is development a gradual, continuous process, or does it pro­

ceed through a sequence of separate stages?

In male or female, y o u n g or old, d e v e l o p ­

ment Is a process of physical, mental, a n d

3. Do our individual traits persist or do we become different per­

sons as we age?

social g r o w t h that continues t h r o u g h o u t life.

57

58

PART

2

Development over the Life S p a n

Let's briefly consider each of these issues and then return to them later

in this and the next chapter.

GENES OR EXPERIENCE?

Our genes are the biochemical units of heredity that make each of us a

distinctive human being. The genes we share are what make us people

rather than dogs or tulips. But might our individual genetic makeups

explain why one person is outgoing, another shy, or why one person is

slow-witted and another smart? Questions like these raise an issue of

profound importance: Are we influenced more by our genes or by our

life experience?

This nature-nurture (or genes-experience) debate has long been

one of psychology's chief concerns. Is behavior, like eye color, pretty

much fixed, or is it changeable? Our answer affects how we view cer­

tain social policies. Suppose that you presume people are the way they

are "by nature." You probably will not have much faith in programs

that try to rehabilitate prisoners or compensate for educational disad­

vantage. And you will probably agree with developmental psycholo­

gists who emphasize the influence of our genes. As a flower unfolds in

accord with its genetic blueprint, so our genes design an orderly se­

quence of biological growth processes called maturation. Maturation

decrees many of our commonalities: standing before walking, using

nouns before adjectives. Although extreme deprivation or abuse will

retard development, the genetic growth tendencies are inherent.

If you take the nurture side of the debate, you probably will agree

with the developmentalists who emphasize external influences. As a

potter shapes a lump of clay, our experiences are presumed to shape

us. This view was argued by the seventeenth-century philosopher

John Locke, who proposed that at birth the child in some ways is an

empty page on which experience writes its story. Although few today

wholeheartedly support Locke's proposition, research provides many

examples of nurture's effects.

In reality, nearly everyone agrees that our behaviors are a product

of the interaction of (1) our genes, (2) our past experience, and (3) the

present situation to which we are responding. Moreover, these factors

sometimes interact. For example, if an attractive, athletic teenage boy

has been treated as a leader and is now sought out by girls, shall we

say his positive self-image is due to his genes or his environment? It's

both, because his environment is reacting to his genetic endowment.

Asking which factor is more important is like asking whether the area

of a football field is due more to its length or to its width.

CONTINUITY

OR

More than 98 percent of our genes are

identical to those of c h i m p a n z e e s . Not

surprisingly, the physiological systems and

even the brain organizations of humans

a n d c h i m p a n z e e s are quite similar.

" M a t u r a t i o n (read the genetic p r o g r a m ,

largely) sets the course of development,

which is modified by experience, espe­

cially if that experience is deviant from

w h a t is normal for the s p e c i e s . "

Sandra Scarr (1982)

STAGES?

Everyone agrees that adults are vastly different from infants. But do

they differ as a giant redwood differs from its seedling—a difference

created by gradual, cumulative growth? Or do they differ as a butterfly

differs from a caterpillar—a difference of distinct stages?

Generally speaking, researchers who emphasize experience and

learning tend to see development as a slow, continuous shaping proc­

ess. Those who emphasize biological maturation tend to see develop­

ment as a sequence of genetically predetermined stages or steps. They

believe that, depending on an individual's heredity and experiences,

progress through the various stages may be quick or slow, but every­

one passes through the same stages in the same order.

Nature or nurture? Stability or c h a n g e ?

For e x a m p l e , h o w m u c h is this o u t g o i n g

b a b y ' s temperament due to her heredity

a n d h o w m u c h to her u p b r i n g i n g ? A n d

h o w likely is it that she will be an o u t g o ­

ing adult? T h e s e questions define t w o

fundamental issues of developmental psy­

chology.

C H A P T E R

3

T h e Developing Child

STABILITY O R C H A N C E ?

For most of this century, psychologists have taken the position that

once a person's personality is formed, it hardens and usually remains

set for life. Researchers who have followed lives through time are now

in the midst of a spirited debate over the extent to which our past

reaches into our future. Is development characterized more by stability

over time or by change? Are the effects of early experience enduring or

temporary? Will the cranky infant grow up to be an irritable adult, or is

such a child just as likely to become a placid, patient person? Do the

differences among classmates in, say, aggressiveness, aptitude, or

strivings for achievement persist throughout the life span? In short, to

what degree do we grow to be merely older versions of our early selves

and to what degree do we become new persons?

Most developmentalists today believe that for certain traits, such as

basic temperament, there is an underlying continuity, especially in the

years following early childhood. Yet, as we age we also change—

physically, cognitively, socially. Thus we have today's life-span view:

Human development is a lifelong process.

PRENATAL D E V E L O P M E N T AND

THE NEWBORN

FROM L I F E C O M E S L I F E

Nothing is more natural than a species reproducing itself. Yet nothing

is more wondrous. Consider human reproduction: The process starts

when a mature ovum (egg) is released by a woman's ovary and the

some 300 million sperm deposited during intercourse begin their race

upstream toward it. When a girl is born, she carries all the eggs she will

ever have, although only a few will ever mature and be released. A

boy, in contrast, begins producing sperm at puberty. The manufactur­

ing process continues 24 hours a day for the rest of his life, although

the rate of production—over 1000 sperm a second—does slow down

with age.

New life is created when egg and sperm unite, and the twentythree chromosomes carried in the egg are paired with the twenty-three

chromosomes brought to it by the sperm. These forty-six chromosomes

contain the master plan for your body (Figure 3 - 1 ) . Each chromosome

is composed of long threads of a molecule called DNA (deoxyribonu­

cleic acid). DNA in turn is made up of thousands of segments, called

genes, that are capable of synthesizing specific proteins (the biochemi­

cal building blocks of life).

Your sex is determined by the twenty-third pair of chromosomes,

the sex chromosomes. The member of the pair that came from your

mother was, invariably, an X chromosome. From your father, you had a

fifty-fifty chance of receiving an X chromosome, making you a female,

or a Y chromosome, making you a male. Biology has become so ad­

vanced that scientists have pinpointed the single tiny gene on the Y

chromosome that seems responsible for throwing the master switch

leading to the production of testosterone, and thus to maleness (Roberts,

1988).

Like space voyagers approaching a huge planet, the sperm ap­

proach a cell 85,000 times bigger than themselves. The relatively few

sperm that make it to the egg release digestive enzymes that eat away

(0

Figure 3 - 1

T h e g e n e s : their location

a n d composition. C o n t a i n e d i n the n u ­

cleus of each of the trillions of cells (a) in

your body are c h r o m o s o m e s (b). Each

c h r o m o s o m e is c o m p o s e d in part of the

molecule D N A (c). G e n e s , which are s e g ­

ments of D N A , form templates for the

production of proteins. By directing the

manufacture of proteins, the g e n e s deter­

mine our individual biological development.

59

60

PART

2

Development over the Life S p a n

the egg's protective coating, allowing one sperm to penetrate (Figure

3 - 2 ) . As it does so, an electrical charge shoots across the ovum's sur­

face, blocking out other sperm during the minute or so that it takes the

egg to form a barrier. Meanwhile, fingerlike projections sprout around

the successful sperm and pull it inward. The egg nucleus and the

sperm nucleus move toward each other and, before half a day has

elapsed, they fuse. The two have become one.

But even at that moment, when one lucky sperm has won the 1 in

300 million lottery, an individual's destiny is not assured. Fewer than

half of fertilized eggs, called zygotes, survive beyond the first week

(Grobstein, 1979), and only a fourth survive to birth (Diamond, 1986).

If human life begins at conception, then most people die without being

born.

But for you and me good fortune prevailed. Beginning as one cell,

each of us became two cells, then four—each cell just like the first.

Then, within the first week, when this cell division had produced a

zygote of approximately 100 cells, the cells began to differentiate—to

specialize in structure and function. Within 2 weeks, the increasingly

diverse cells became attached to the mother's uterine wall, beginning

approximately 37 weeks of the closest human relationship (see Figure

3-3).

During the ensuing 6 weeks, the developing human is called an

embryo. In this embryonic period the organs begin to form and may

begin to function: The heart begins to beat and the liver begins to make

red blood cells. By the ninth week, the embryo has become unmistak­

ably human and is called a fetus. By the end of the sixth month, inter­

nal organs such as the stomach have become sufficiently formed and

functional that they allow a prematurely born fetus a chance of sur­

vival.

Nutrients and oxygen in the mother's blood pass through the pla­

centa into the blood of the fetus. If the mother is severely malnourished

during the last third of the pregnancy, when the demand for nutrients

reaches a peak, the baby may be born prematurely—or even be

stillborn.

(a)

Figure 3 - 3

Prenatal development.

(b)

Figure 3 - 2

D e v e l o p m e n t begins w h e n a

sperm unites with an e g g . T h e resulting

z y g o t e is a single cell that, if all g o e s well,

will become a 100-trillion-cell h u m a n

being.

Prenatal stages

Zygote:

Embryo:

Fetus:

conception to 2 weeks.

2 weeks through 8 weeks.

9 weeks to birth.

(d)

(c)

the body is n o w b i g g e r than the head,

fetus to the wall of the uterus and

(a) T h e e m b r y o g r o w s and develops rap­

and the arms and legs have g r o w n n o ­

t h r o u g h which the fetus is nourished, is

idly. At 40 d a y s , the spine is visible and

ticeably, (c) By the end of the second

clearly visible in this photo.) (d) As the

the arms and legs are b e g i n n i n g to g r o w .

month, w h e n the fetal period begins,

fetus enters the fourth m o n t h , it w e i g h s

(b) Five days later the e m b r y o ' s propor­

facial features, hands, and feet have

a b o u t 3 ounces.

tions have b e g u n to c h a n g e . T h e rest of

f orm ed. (The placenta, which attaches the

C H A P T E R

Along with nourishment, harmful substances, called teratogens,

can pass through or harm the placenta—with potentially tragic effects.

If the mother is a heroin addict, her baby is born a heroin addict. If she

is a heavy smoker, her newborn is likely to be underweight, sometimes

dangerously so (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

1983a). If she drinks much alcohol, her baby is at greater risk for birth

defects and mental retardation (Raymond, 1987). If she carries the

AIDS virus, her baby will often be infected as well (Minkoff, 1987).

3

T h e Developing Child

Tera literally means " m o n s t e r " ; teratogens

are " m o n s t e r - p r o d u c i n g " agents, such as

chemicals and viruses, that may harm the

fetus.

THE C O M P E T E N T N E W B O R N

Newborns come equipped with reflexes that are ideally suited for sur­

vival. The infants will withdraw a limb to escape pain; if a cloth is put

over their faces, interfering with their breathing, they will turn their

heads from side to side and swipe at it. New parents are often awed by

the coordinated sequence of reflexes by which babies obtain food. The

rooting reflex is one example: When their cheeks are touched, babies

will open their mouths and vigorously "root" for a nipple. Finding

one, they will automatically close on it and begin sucking—which itself

requires a coordinated sequence of tonguing, swallowing, and breath­

ing. Failing to find satisfaction, the hungry baby may cry—a behavior

that parents are predisposed to find highly unpleasant to hear and very

rewarding to relieve.

The pioneering American psychologist William James (who once

said, "The first lecture on psychology I ever heard was the first I ever

gave") presumed that the newborn experiences a "blooming, buzzing

confusion." Until the 1960s few people disagreed. It was said that,

apart from a blur of meaningless light and dark shades, newborns

could not see. Then, just as the development of new technology led to

a surge of progress in the neurosciences, so too did new investigative

techniques enhance the study of infants. Scientists discovered that

babies can tell you a lot—if you know how to ask. To ask, you must

capitalize on what the baby can do—gaze, suck, turn the head. So,

equipped with eye-tracking machines, pacifiers wired to electronic

gear, and other such devices, researchers set out to answer parents'

age-old question: What can my baby see, hear, smell, and think?

"It is a rare privilege to watch the birth,

g r o w t h , and first feeble struggles of a liv­

ing human m i n d . "

Annie Sullivan, in Helen Keller's

The Story of My Life,

1903

They discovered that a baby's sensory equipment is "wired" to

facilitate social responsiveness. Newborns turn their heads in the di­

rection of human voices, but not in response to artificial sounds. They

gaze more at a drawing of a human face than at a bull's-eye pattern; yet

they gaze more at a bull's-eye pattern—which has contrasts much like

that of the human eye—than at a solid disk (Fantz, 1961). They focus

best on objects about 9 inches away, which, wonder of wonders, just

happens to be the typical distance between a nursing infant's eyes and

the mother's. Newborns, it seems, arrive perfectly designed to see

their mothers' eyes first of all.

Babies' perceptual abilities are continuously developing during the

first months of life. Within days of birth, babies can distinguish their

mothers' facial expression, odor, and voice. A week-old nursing baby,

placed between a gauze pad from its mother's bra and one from an­

other nursing mother, will generally turn toward the smell of its own

mother's pad (MacFarlane, 1978). At 3 weeks of age, an infant who is

allowed to suck on a pacifier that sometimes turns on recordings of its

mother's voice and sometimes that of female stranger, will suck more

vigorously when it hears its mother's voice (Mills & Melhuish, 1974).

So not only can infants see what they need to see, and smell and hear

well, but they are already using their sensory equipment to learn.

Studies like the one under w a y in this

M I T lab are exploring infants' abilities to

perceive, think, a n d remember. This infant

is being tested on pattern perception.

Experiments have demonstrated that even

very y o u n g infants are capable of sophis­

ticated visual discrimination. T h e y often

s h o w a marked preference for one picture

over another, a n d will also look m u c h

longer at an unfamiliar pattern than at

one which they have seen before. S u c h

tests have c h a n g e d psychologists' ideas of

w h a t the world looks like to a baby.

62

PART

2

Development over the Life S p a n

Two teams of investigators have reported the astonishing and con­

troversial finding that, in the second week—or even the first hour of

life—infants tend to imitate facial expressions (Field & others, 1982;

Meltzoff & Moore, 1983, 1985).

If such findings can be substantiated by additional research, it will

be a further tribute to the newborn's competence. Consider: How do

newborn babies relate their own facial movements to those of an adult?

And how can they coordinate the movements involved? The findings

are controversial because they contradict what most people have pre­

sumed to be the newborn's very limited sensory and motor abilities.

Researcher Tiffany Field (1987) notes that "Our knowledge of in­

fancy was in its infancy 20 years ago, but what we have learned since

then has dramatically changed the way we perceive and treat infants."

More and more, psychologists see the baby as "a very sophisticated

perceiver of the world, with very sensitive social and emotional quali­

ties and impressive intellectual abilities." The "helpless infant" of the

1950s has become the "amazing newborn" of the 1980s.

Imitation? W h e n A n d r e w Meltzoff s h o w s

his t o n g u e , an 1 8 - d a y - o l d boy responds

similarly. " A s our experimental techniques

have become more a n d more sophisti­

INFANCY AND C H I L D H O O D

During infancy, a baby grows from newborn to toddler, and during

childhood from toddler to teenager. Beginning in this chapter with

infancy and childhood and continuing in the next chapter with adoles­

cence through old age, we will see how people of all ages are continu­

ally developing—physically, cognitively, and socially.

PHYSICAL

c a t e d , " reports Meltzoff ( 1 9 8 7 ) , " t h e in­

fants themselves have appeared more a n d

more c l e v e r . "

DEVELOPMENT

Brain D e v e l o p m e n t While you resided in your mother's womb,

your body was forming nerve cells at the rate of about one-quarter

million per minute. On the day you were born you had essentially all

the brain cells you were ever going to have. However, the human

nervous system is immature at birth; the neural networks that enable

us to walk, talk, and remember are only beginning to form (see

Figure 3 - 4 ) .

Along with the development of neural networks we see increasing

myelinization of neurons. (As we saw in Chapter 2, myelin is a fatty

cell that encases the axon, enabling messages to speed many times

faster.) The nerve fibers that monitor and coordinate bladder control,

for example, are not fully myelinated until the second year. To expect a

toddler to do without a diaper before then is to court disaster.

The storage of permanent memory also requires neural develop­

ment. Our earliest memories go back only to between our third and

fourth birthdays (Kihlstrom & Harachkiewicz, 1982). For parents, this

"infantile amnesia," as Freud called it, can be disconcerting. After all

the hours we spend with our babies—after all the frolicking on the rug,

all the diapering, feeding, and rocking to sleep—what would they con­

sciously remember of us if we died? Nothing!

But if nothing is consciously recalled, something has still been

gained. From birth (and even before), infants can learn. They can learn

to turn their heads away to make an adult "peekaboo" at them, to pull

a string to make a mobile turn, to turn their heads to the left or right to

receive a sugar solution when their forehead is stroked (Blass, 1987;

Bower, 1977; Lancioni, 1980). Such learning tends not to persist unless

At birth

6 months

Figure 3 - 4

1 month

15 months

3 months

2 years

In h u m a n s , the brain is

immature at birth. T h e s e drawings of sec­

tions of brain tissue from the cerebral cor­

tex illustrate the increasing complexity of

the neural networks in the maturing

h u m a n brain.

C H A P T E R

reactivated. Nevertheless, early learning may prepare our brains for

those later experiences that we do remember. For example, children

who become deaf at age 2, after being exposed to speech, are later

more easily language trained than those deaf from birth (Lenneberg,

1967). It has been suggested that the first 2 years are therefore critical

for learning language.

Animals such as guinea pigs, whose brains are mature at birth,

more readily form permanent memories from infancy than do animals

with immature brains, such as rats (Campbell & Coulter, 1976). Be­

cause human brains are also immature at birth, these findings cast

doubt on the idea that people subconsciously remember their prenatal

life or the trauma of their birth. But, given occasional reminders,

3-month-old infants who learn that moving their leg propels a mobile

will indeed remember the association for at least a month (RoveeCollier, 1988)—so some infant memory does exist.

Does experience, as well as biological maturation, help develop the

brain's neural connections? Although "forgotten," early learning may

help prepare our brains for thought and language, and for later experi­

ences. Surely our early learning must somehow be recorded "in

there."

If early experiences affect us by leaving their "marks" in the brain,

then it should be possible to detect evidence of this. The modern tools

of neuroscience allow us a closer look. Working at the University of

California, Berkeley, Mark Rosenzweig caged some rats in solitary con­

finement, while others were caged in a communal playground (Figure

3-5). Rats living in the deprived environment usually developed a

lighter and thinner cortex with smaller nerve cell bodies, as well as

fewer glial cells (the "glue cells" that support and nourish the brain's

neurons). Rosenzweig (1984a; Renner & Rosenzweig, 1987) reported

being so surprised by these effects of experience on brain tissue that he

repeated the experiment several times before publishing his findings—

findings that have led to improvements in the environments provided

for laboratory and farm animals and for institutionalized children.

Other recent studies extended these findings. Several research

teams have found that infant rats and premature babies benefit from

the stimulation of being touched or massaged (Field & others, 1986;

Meaney & others, 1988). "Handled" infants of both species gain

weight more rapidly and develop faster neurologically. In adulthood,

handled rat pups also secrete less of a stress hormone that during

aging causes neuron death in the hippocampus, a brain center impor­

tant for memory. William Greenough and his University of Illinois co­

workers (1987) further discovered that repeated experiences sculpt a

rat's neural tissue—at the very spot in the brain where the experience

is processed. This sculpting seems to work by preserving activated

neural connections while allowing unused connections to degenerate.

3

T h e Developing Child

Impoverished

environment

Enriched

environment

Figure 3 - 5

Experience affects the

brain's development. In experiments pio­

neered by M a r k R o s e n z w e i g and D a v i d

K r e c h , rats were reared either alone in an

More and more, researchers are becoming convinced that the

brain's neural connections are dynamic; throughout life our neural tis­

sue is changing. Our genes dictate our overall brain architecture, but

experience directs the details. If a monkey is trained to push a lever

with a finger several thousand times a day, the brain tissue that con­

trols the finger changes to reflect the experience. The wiring of Michael

Jordan's brain reflects the thousands of hours he has spent shooting

baskets. Experience, it seems, helps nurture nature.

environment without playthings or with

Motor Development As the infant's muscles and neural networks

mature, ever more complicated skills emerge. Although the age at

M. C. D i a m o n d . C o p y r i g h t © 1 9 7 2 S c i e n ­

others in an environment enriched with

playthings that were c h a n g e d daily. In

fourteen out of sixteen repetitions of this

basic experiment, the rats placed in the

enriched environment developed signifi­

cantly more cerebral cortex relative to the

rest of the brain's tissue than those in the

impoverished environment. (From " B r a i n

c h a n g e s in response to e x p e r i e n c e " by

M. R. R o s e n z w e i g , E. L Bennett, and

tific A m e r i c a n , Inc. All rights reserved.)

63

which infants sit, stand, and walk varies from child to child, the se­

quence in which babies pass these developmental milestones (Figure

3 - 6 ) is universal.

Can experience retard or speed up the maturation of physical

skills? If babies were bound to a cradleboard for much of their first

year—the traditional practice among the Hopi Indians—would they

walk later than do unbound infants? If allowed to spend an hour a day

in a walker chair after age 4 months, would they walk earlier? Amaz­

ingly, in view of what we now know about the effects experience has

on the brain, the answer to both questions seems to be no (Dennis,

1940; Ridenour, 1982).

Biological maturation—including the rapid development of the

cerebellum at the rear of the brain—creates a readiness to learn walk­

ing at about 1 year of age. Experience before that time has no more

than a small effect, although restriction later may retard development

(Super, 1981). This is true for other physical skills, including bowel and

bladder control. Until the necessary muscular and neural maturation

has occurred, no amount of pleading, harassment, or punishment can

lead to successful toilet training.

After a spurt during the first 2 years, growth slows to a steady 2 to

3 inches per year through childhood. With all of the neurons and most

of their interconnections in place, brain development after age 2 simi­

larly proceeds at a slower pace. The sensory and motor cortex areas

continue to mature relatively rapidly, enabling fine motor skills to de­

velop further (R. Wilson, 1978). The association areas of the cortex—

those associated with thinking, memory, and language—are the last

brain areas to develop.

C H A P T E R

3

T h e Developing Child

COGNITIVE D E V E L O P M E N T

Brain scans and brain wave analyses reveal that the development of

different brain areas during infancy and childhood corresponds closely

with cognitive development (Chugani & Phelps, 1986; Thatcher & oth­

ers, 1987). Brain and mind develop together. Cognition refers to all the

mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, and remember­

ing. Few questions have intrigued developmental psychologists more

than these: When can children begin to remember? See things from

another's point of view? Reason logically? Think symbolically? Simply

put, how does a child's mind grow? Such were the questions posed by

developmental psychologist Jean Piaget (pronounced Pea-ah-ZHAY).

"Who knows the thoughts of a child?" wondered poet Nora Perry.

As much as anyone of his generation, Piaget knew. His interest in

children's cognitive processes began in 1920, when he was working in

Paris to develop questions for children's intelligence tests. In the

course of administering tests to find out at what age children could

answer certain questions correctly, Piaget became intrigued by

children's wrong answers. Where others saw childish mistakes, Piaget

saw intelligence at work. He observed that the errors made by children

of a given age were often strikingly similar.

The more than 50 years Piaget spent in such informal activities

with children convinced him that the child's mind is not a miniature model

of the adult''s: Young children actively construct their understandings of

the world in radically different ways than adults do, a fact that we

overlook when attempting to teach children by using our adult logic.

Piaget further believed that the child's mind develops through a series

of stages, in an upward march from the sensorimotor simplicity of the

newborn to the abstract reasoning power of the adult. An 8-year-old

child therefore comprehends things that a 3-year-old cannot. An

8-year-old might grasp the analogy "getting an idea is like having a

light turn on in your head," but trying to teach the same analogy to a

3-year-old would be fruitless.

Jean Piaget ( 1 9 3 0 , p. 2 3 7 ) : " I f we e x a m ­

ine the intellectual d e v e l o p m e n t of the

individual or of the whole of humanity,

we shall find that the h u m a n spirit g o e s

t h r o u g h a certain n u m b e r of stages, each

different from the o t h e r . "

" F o r everything there is a season, and a

time for every matter under h e a v e n . "

How the Mind of a Child Grows The driving force behind this

intellectual progression is the unceasing struggle to make sense out of

one's world. To this end, the maturing brain builds concepts, which

Piaget called schemas. Schemas are ways of looking at the world that

organize our past experiences and provide a framework for under­

standing our future experiences. We start life with simple schemas—

those involving sense-driven reflexes such as sucking and grasping. By

adulthood we have built a seemingly limitless number of schemas that

range from knowing how to tie a knot to knowing what it means to be

in love.

Piaget proposed two concepts to explain how we use and adjust

our schemas. First, we interpret our experience in terms of our current

understandings; in Piaget's terms, we incorporate, or assimilate, new

experiences into our existing schemas.

Assimilation is interpreting new experiences in light of one's sche­

mas, as when a toddler calls all four-legged animals "doggies." But we

also adjust, or accommodate, our schemas to fit the particulars of new

experiences. The child learns fairly quickly that the original "doggie"

schema is too broad, and accommodates by refining the category.

When new experiences just will not fit our old schemas, our schemas

may change to accommodate the experiences. When prejudiced people

perceive a minority person through their preconceived ideas, they are

assimilating. When experience forces them to modify their former

schemas, they are accommodating.

Ecclesiastes 3:1

Look carefully at the "devil's tuning fork"

below.

N o w look a w a y — n o , better first study it

some m o r e — a n d then look away and

draw it. Not so easy, is it? Because this

tuning fork is an impossible object, you

have no s c h e m a into which you can as­

similate what y o u see.

65

66

PART

2

Development over the Life S p a n

Highly realistic art is easy to assimilate; it

requires for interpretation only those schemas already available from observing the

Science itself is a process of assimilation and accommodation. Sci­

entists interpret nature using their preconceived theories—for exam­

ple, that newborns are passive, incompetent creatures—to assimilate

what would otherwise be a bewildering body of disconnected observa­

tions. Then, as new observations collide with these theories, the theo­

ries must be changed or replaced to accommodate the findings. Thus the

new concept of the newborn as competent and active replaces the old

schema. That, Piaget believed, is how children (and adults) construct

reality using both assimilation and accommodation. What we know is

not reality exactly as it is, but our constructions of it.

world. Highly abstract art is difficult to

assimilate, which m a y explain the frustra­

tion it sometimes causes. W h e n art c o m ­

bines realism with abstraction, it allows

observers to impose m e a n i n g by stimulat­

ing them to stretch their schemas.

Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Stages Piaget went on to describe

cognitive development as occurring in four major stages (Table 3 - 1 ) .

P I A G E T ' S S T A C E 5 O F COGNITIVE D E V E L O P M E N T

Approximate age

Description of stage

Developmental milestones

Birth—2 years

Sensorimotor

Infant experiences the world through

senses and actions (looking, touching,

mouthing).

Object permanence (page 67);

stranger anxiety (page 68).

2 - 6 years

7 - 1 2 years

Teen years

Preoperational

Child represents things with words

and images, but cannot reason with logic.

Ability to pretend (page 67);

egocentrism (page 68).

Concrete operational

Child thinks logically about concrete

events; can grasp concrete analogies

and perform arithmetical operations.

Conservation (page 69);

mathematical transformations

(page 69).

Formal operational

Teenager develops abstract reasoning.

Scientific reasoning (page 92);

potential for mature moral

reasoning (pages 9 2 - 9 5 ) .

C H A P T E R

3

T h e Developing Child

T h e sensorimotor stage of development

b e g i n s in infancy a n d continues until

a b o u t a g e 2 . Very y o u n g children explore

The developing child, he believed, moves from one age-related plateau

to the next. Each plateau has distinctive characteristics that permit spe­

cific kinds of thinking. The differences between these kinds of thinking

are qualitative: They involve changes in the way the child thinks.

During the first stage, which occurs between birth and approxi­

mately age 2, infants are limited to sensorimotor intelligence: Their under­

standing of the world is restricted to their interactions with objects

through their senses and motor activity—through looking, touching,

sucking, grasping, and the like. In the preschool years of 2 to 6 most

children demonstrate preoperational intelligence: They can think about

objects without physically interacting with them, which means they

can begin to think about objects in a simple symbolic way.

This new type of thinking is reflected in the preschooler's ability to

pretend, to think about past events and anticipate future ones, and to

begin to use language. Children in the preoperational stage are not

able, however, to think in a truly logical fashion. They may figure out

that five plus three is eight and not instantly realize that three plus five

is also eight.

Beginning at about age 7, children demonstrate concrete operational

intelligence: They can perform the mental operations that produce logi­

cal thought, but they are able to think logically only about concrete

things. It is not until about age 12, when children enter the stage of

formal operational intelligence, that they are able to begin to think

hypothetically and abstractly. To appreciate how the mind of a child

grows, let's look more closely at each of these stages.

Sensorimotor Stage

During the sensorimotor stage, infants under­

stand their world in terms of their senses and the effects of their ac­

tions; they are aware only of what they can see, smell, suck, taste, and

grasp, and at first they seem to be unaware that things continue to exist

apart from their perceptions.

In one of his tests, Piaget would show an infant an appealing toy

and then flop his beret over it to see whether the infant searched for

the toy. Before the age of 8 months, they did not. They lacked object

permanence—the awareness that objects continue to exist when not

perceived. The infant lives in the present. What is out of sight is out of

mind. By 8 months, infants begin to develop what psychologists now

believe is a memory for things no longer seen. Hide the toy and the

the world t h r o u g h their senses, e n j o y i n g

the smell, feel, and taste of almost a n y ­

t h i n g they c a n g e t their hands o n . As the

child m o v e s into the preoperational stage,

at the a g e of a b o u t 18 months, pretend­

ing becomes possible. This child's imagi­

nation is still expressed t h r o u g h simple

c a r e - g i v i n g ; in another year the pretend

activities will b e c o m e m u c h more elabo­

rate.

" C h i l d r e n think not of what is past, nor

w h a t is to c o m e , but enjoy the present

time, which few of us d o . "

L a Bruyere, 1 6 4 5 - 1 6 9 6

Les

caraderes:

De

I'homme

67

68

PART

2

D e v e l o p m e n t over the Life S p a n

O b j e c t permanence. Y o u n g e r children lack

the sense that things continue to exist

w h e n not in sight; but for this 8 / 2 - m o n t h 1

infant will momentarily look for it. Within another month or two, the

infant will look for it even after being restrained for several seconds.

This flowering of recall occurs simultaneously with the emergence

of a fear of strangers, called stranger anxiety. Watch how infants of

different ages react when handed over to a stranger and you will notice

that, beginning at 8 or 9 months, they often will cry and reach for their

familiar caregivers. Is it a mere coincidence that object permanence and

stranger anxiety develop together? Probably not. After about 8 months

of age, the child has schemas for familiar faces; when a new face cannot

be assimilated into these remembered schemas, the infant becomes

distressed (Kagan, 1984). This link between cognitive development

and social behavior illustrates the interplay of brain maturation, cogni­

tive development, and social development.

Preoperational Stage

Seen through the eyes of Piaget, preschool chil­

dren are still far from being short grownups. Although aware of them­

selves, of time, and of the permanence of objects, they are, he said,

egocentric: They cannot perceive things from another's point of view.

The preschooler who blocks your view of the television while trying to

see it herself and the one who asks a question while you are on the

phone both assume that you see and hear what they see and hear.

When relating to a young child, it may help to remember that such

behaviors reflect a cognitive limitation: The egocentric preschooler has

difficulty taking another's viewpoint.

Preschoolers also find it easier to follow positive instructions

("Hold the puppy gently") than negative ones ("Don't squeeze the

puppy"). One characteristic of parents who abuse their children is that

they generally have no understanding of these limits. They perceive

their children as junior adults who are in control of their behavior

(Larrance & Twentyman, 1983). Thus children who stand in the way,

spill food, disobey negative instructions, or cry may be perceived as

willfully malicious.

Just before age 3 children do, however, become more capable of

thinking symbolically. Judy DeLoache (1987) discovered this when she

showed a group of ZV^-year-dlds a model of a room and hid a model toy

in it (say a miniature stuffed dog behind a miniature couch). The chil­

dren could easily remember where to find the miniature toy, but could

not readily locate the actual stuffed dog behind the couch in the real

room. When 3-year-olds were given a look at the model room, how­

ever, they would usually go right to the actual stuffed animal in the

old child, out of sight is not out of mind.

C H A P T E R

3

T h e Developing Child

real room, showing that they could think of the model as a symbol for

the room.

Piaget believed that during this preschool period and up to about

age 7, children are in what he called the preoperational stage—unable

to perform mental operations. For a 5-year-old, the quantity of milk

that is "too much" in a tall, narrow glass may become an acceptable

amount if poured into a short, wide glass. This is because the child

focuses only on the height dimension, and is incapable of reversing the

operation by mentally pouring it back. The child lacks the concept of

conservation—the principle that the quantity of a substance remains

the same despite changes in its shape. Children's conversations con­

firm this inability to reverse information (Phillips, 1969, p. 61):

"Do you have a brother?"

"Yes."

"What's his name?"

"Jim."

"Does Jim have a brother?"

"No."

Concrete Operational Stage With older children, Piaget would roll

one of two identical balls of clay into a rope shape and ask whether

there was more clay in the rope or the ball. Children who are in the

preoperational stage almost always say that the rope has more clay

because they assume "longer is more." They cannot mentally reverse

the clay-rolling process to see that the amount of clay is the same in

both shapes. But children who are in the concrete operational stage

realize that a given quantity remains the same no matter how its shape

changes. Piaget contended that during the stage of concrete operations

(roughly ages 7 to 12) children acquire the mental operations needed to

comprehend mathematical transformations and conservation. When

my daughter Laura was age 6, I was astonished at her inability to

reverse arithmetic operations—until considering Piaget. Asked, "What

is eight plus four?" she required 5 seconds to compute "twelve," and

another 5 seconds to then compute twelve minus four. By age 8, she

could reverse the process and answer the second question instantly.

Although the operations usually must involve concrete images of

physical actions or objects, not abstract ideas, preteen children exhibit

logic. Eleven-year-olds can mentally pour the milk back and forth be­

tween different-shaped glasses, so they realize that change in shape

does not mean change in quantity. They also enjoy jokes that allow

them to utilize their recently acquired concepts, such as conservation:

Mr. Jones went into a restaurant and ordered a whole pizza for his dinner.

When the waiter asked if he wanted it cut into 6 or 8 pieces, Mr. Jones

said, "Oh, you'd better make it 6, I could never eat 8 pieces!" (McGhee,

1976)

If Piaget was correct that children construct their understandings

through assimilation and accommodation, and that in early childhood

their thinking is radically different from adult thinking, what are the

implications for preschool and elementary school teachers? Might

teachers capitalize on what comes naturally to children? Believing that

children actively construct their own understandings, Piaget con­

tended that teachers should strive to "create the possibilities for a child

to invent and discover." Build on what children already know, allow

them to touch and see, to witness concrete demonstrations, to think for

themselves. Exploit their natural ways of thinking and learning. Be­

cause the young child is incapable of adult logic, teachers must under-

T h e preoperational child cannot perform

the mental operations essential to under­

standing conservation. A glass of milk

seems to be " m o r e " after being poured

into a tall, narrow g l a s s .

69

70

PART

2

Development over the Life S p a n

Piaget's writings have influenced m a n y

educators to provide children with situa­

tions a n d e n c o u r a g e m e n t that will prompt

t h e m to do their o w n exploring a n d dis­

stand how children think, and therefore realize that what is simple and

obvious to them—that subtraction is the reverse of addition—may be

incomprehensible to a 6-year-old.

Reflections on Piaget's Theory

Piaget's stage theory is controversial.

Do children's cognitive abilities really go through distinct stages? Does

object permanence in fact appear rather abruptly, much as a tulip blos­

soms in spring? Today's researchers contend that we have underesti­

mated the competence of young children. Given very simple tasks,

preschoolers are not purely egocentric; they will adjust their explana­

tions to make them clearer to a listener who is blindfolded, and will

show a toy or picture with the front side facing the viewer (Gelman,

1979; Siegel & Hodkin, 1982). If questioned in a way that makes sense

to them, 5- and 6-year-olds will exhibit some understanding of conser­

vation (Donaldson, 1979). It seems, then, that the abilities to take an­

other's perspective and to perform mental operations are not utterly

absent in the preoperational stage—and then suddenly appear.

Rather, these abilities begin earlier than Piaget believed and develop

more gradually.

What remains of Piaget's ideas about the mind of the child? Plenty.

For Piaget identified and named important cognitive phenomena and

helped stimulate interest in studying how the mind develops. That we

today are adapting his ideas to accommodate new findings would not

surprise him.

SOCIAL

DEVELOPMENT

As we have seen, babies are social creatures from birth. Almost from

the start, parent and baby communicate through eye contact, touch,

smiles, and voice. The end result is social behavior that promotes in­

fants' survival and their emerging sense of self, so that they, too, even­

tually may bear and nurture a new generation.

In all cultures, infants develop an intense bond with those who

care for them. Beginning with newborns' attraction to humans in gen­

eral, infants soon come to prefer familiar faces and voices and then to