9 – 1977 - Sanpete County

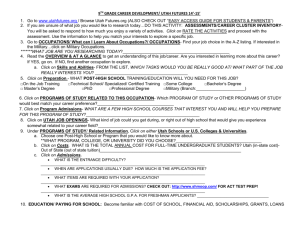

advertisement