Toward a Rewriting of Classic Literature: Biblical

advertisement

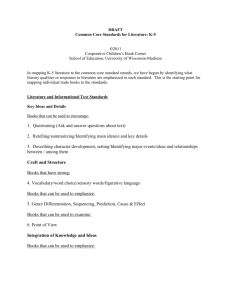

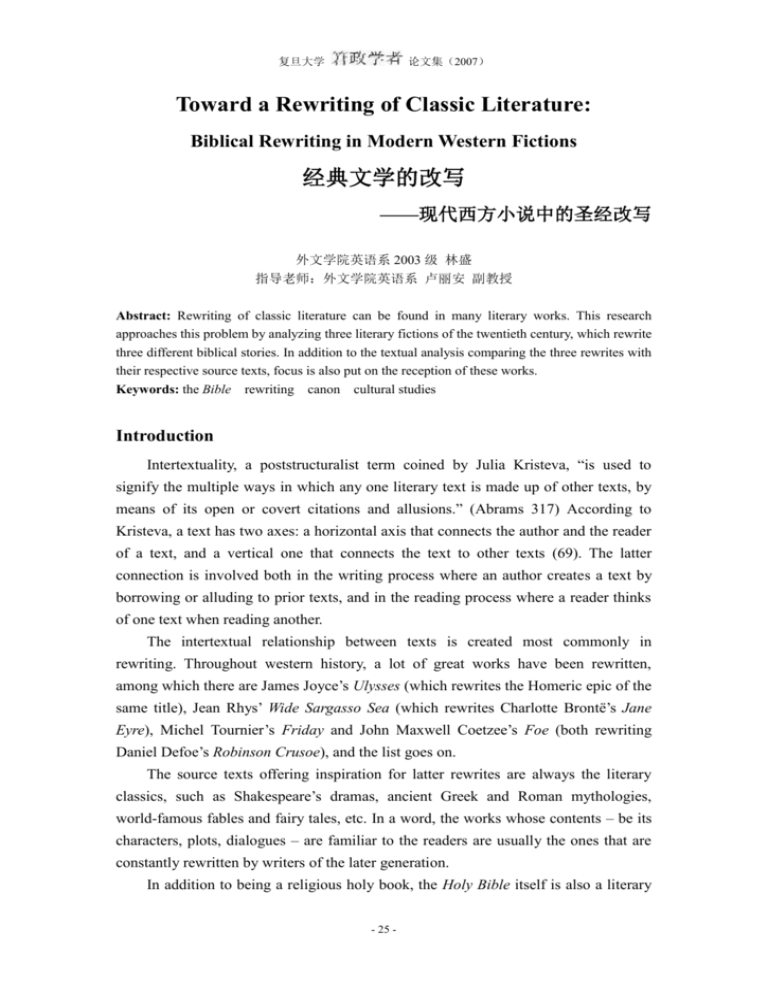

复旦大学 论文集(2007) Toward a Rewriting of Classic Literature: Biblical Rewriting in Modern Western Fictions 经典文学的改写 ——现代西方小说中的圣经改写 外文学院英语系 2003 级 林盛 指导老师:外文学院英语系 卢丽安 副教授 Abstract: Rewriting of classic literature can be found in many literary works. This research approaches this problem by analyzing three literary fictions of the twentieth century, which rewrite three different biblical stories. In addition to the textual analysis comparing the three rewrites with their respective source texts, focus is also put on the reception of these works. Keywords: the Bible rewriting canon cultural studies Introduction Intertextuality, a poststructuralist term coined by Julia Kristeva, “is used to signify the multiple ways in which any one literary text is made up of other texts, by means of its open or covert citations and allusions.” (Abrams 317) According to Kristeva, a text has two axes: a horizontal axis that connects the author and the reader of a text, and a vertical one that connects the text to other texts (69). The latter connection is involved both in the writing process where an author creates a text by borrowing or alluding to prior texts, and in the reading process where a reader thinks of one text when reading another. The intertextual relationship between texts is created most commonly in rewriting. Throughout western history, a lot of great works have been rewritten, among which there are James Joyce’s Ulysses (which rewrites the Homeric epic of the same title), Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea (which rewrites Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre), Michel Tournier’s Friday and John Maxwell Coetzee’s Foe (both rewriting Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe), and the list goes on. The source texts offering inspiration for latter rewrites are always the literary classics, such as Shakespeare’s dramas, ancient Greek and Roman mythologies, world-famous fables and fairy tales, etc. In a word, the works whose contents – be its characters, plots, dialogues – are familiar to the readers are usually the ones that are constantly rewritten by writers of the later generation. In addition to being a religious holy book, the Holy Bible itself is also a literary - 25 - 现代西方小说中改写经典文学的现象与问题分析 work. The first book of the Holy Bible, “Genesis”, tells the story of the first man and woman, and of their descendants. The four Gospels in the New Testament tell basically an identical life story of Jesus Christ. These stories are familiar not only to western religious believers, but also to other non-believers around the world. Since the stories in the Bible are familiar to people, the Holy Bible has always been an abundant source for rewriting. Even great writers have attempted to rewrite biblical stories, famous or less well-known. The most celebrated rewritings include John Milton’s Samson Agonistes, which retells the stories of Samson in Judges, Oscar Wilde’s Salome, whose story is told in the gospel of Mark, though only obliquely. On account of the importance of the Bible as a work of literature and as a source of literary rewriting, this paper intends to reflect on the problems of rewriting biblical literature by closely examining three examples of modern western fictions: The Diaries of Adam and Eve (1905) by Mark Twain, “The Gospel According to Mark” (1970) by Jorge Luis Borges, and A History of the World in 10½ Chapters (1989) by Julian Barnes. The three fictional narratives will be examined on their respective allusions to the Bible. The research will focus on how the ancient stories in the Holy Bible are revisited and revived, to what extent and on what aspects they are rewritten, be it the theme, the characters, or the religious doctrines. Since rewriting of biblical stories is concerned with religion, attention will also be attributed to the research of the authors’ religious background: What religious attitude does the author hold toward biblical rewriting? Is he a strong believer of religion? What is his intention in rewriting the chosen biblical stories? Other things such as the authors’ life experience and literary characteristics are also within concern. Literary texts, positioned within the scope of cultural studies, are taken as cultural products, and therefore, to understand the impact of particular texts, the interplay between production, distribution and consumption must also be reckoned. Under such circumstances, a study of literary texts has to include not only the study on the part of the authors, but also that on the part of the readers and on the part of those who make the authors’ works available to readers. Therefore, in addition to the textual analysis of the authors’ rewrites, focus will also be put on the reception of these works. It is equally important to take into account the social environment which makes it possible for the readers to get to know the author’s works. Why are these rewrites accepted by the authority while others are not, and therefore are kept out of the readers’ vision? In a word, this research intends to approach the problem of biblical rewriting - 26 - 复旦大学 论文集(2007) through the vision of cultural studies, and explore why these rewrites are accepted. This thesis will approach the problem of rewriting biblical stories in four chapters. Chapter 1 will give a brief account of the three chosen texts. Chapter 2 will examine the three texts closely of their respective allusions to the Holy Bible, and explore the intentions of the authors in rewriting the Bible. Chapter 3 will elaborate on the reception of the three rewrites. Chapter 4 will be a conclusion. Chapter 1 Literature Review 1.1 An Overview of the Selected Texts 1.1.1 The Diaries of Adam and Eve (1905) The Diaries of Adam and Eve (Diaries for short below) is written by the world-famous American humorist Mark Twain (1835-1910), in his later years. It consisted originally of two novellas: Extracts from Adam’s Diary (1893), and Eve’s Diary (1905). Most of Extracts from Adam’s Diary had been finished before 1893, when Twain was invited to write a humorous piece about Niagara Falls to be part of a souvenir book for the 1893 World Fair to be held in Buffalo, New York. At first he declined, but later inspiration stroke him that he relocated the story of Adam’s diary to an Eden that contained Niagara Falls, which was published first in The Niagara Book. Eve’s Diary was written as a contribution to the 1905 Christmas issue of Harper’s Magazine. Hoping for the magazine to publish the two diaries together, he considered revising Adam’s by cutting seven hundred words and writing some new pages in Adam’s voice to be included in Eve’s Diary. However, the magazine published only Eve’s Diary, and the two first appeared together in The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories in 1906. As the book title reveals, this novella is written in the form of diaries, narrated respectively in the voice of Adam and Eve. The two diaries have a basically identical background of time, beginning from when God created Adam and Eve until Eve’s death. 1.1.2 “The Gospel According to Mark” (1970) The title, “The Gospel According to Mark” (“Gospel” for short below), has a clear air of biblical allusion to the gospel of Mark in the New Testament. It was originally written in Spanish, by the famous Argentine writer, poet and scholar, Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), and was included in his collection of short stories, Doctor Brodie’s Report (1970). It was first translated and published in English in 1972. The protagonist of this story, Baltasar Espinosa, was a medical student from - 27 - 现代西方小说中改写经典文学的现象与问题分析 Buenos Aires. He was invited to spend the summer months at La Colorada ranch, where he met the foreman Gutre and his family, who were descendants of Scotland natives, and were hardly educated. One day, a storm struck, and the ranch was flooded and isolated from the outside world. Espinosa came across an English Bible in the house and read the Gospel according to Saint Mark to the Gutres, who, seemingly having understood what Espinosa had read to them, regarded him as Jesus Christ who was able to rescue them from the flood and others. Finally, after another storm broke out, the Gutres crucified Espinosa for the purpose of their salvation. 1.1.3 A History of the World in 10½ Chapters (1989) Novelist Julian Barnes was born in Leicester, UK in 1946. After his graduation from college, he worked as lexicographer, journalist, literary editor, before he took up the writing career and published his first novel in 1980. This novel, written in 1989, A History of the World in 10½ Chapters (History for short below), is distinctive in its form. As its title suggests, the whole book contains 10 full chapters and one parenthesis, half in length of the others. Each chapter has little relationship with one another at surface except that the stories are all about boats on the sea. The book opens with the first chapter “The Stowaway” which retells the biblical story of the Flood and Noah’s Ark. The story is told in the voice of a woodworm that got stowed away on Noah’s Ark. As a participant in the biblical event, it discloses information that is not told in the Holy Bible, such as the loss of Noah’s fourth son, Varadi (in addition to his three brothers, Shem, Ham, and Japheth, who are recorded in the Holy Bible) and his ship with one fifth of the species that are on it. 1.2 A Justification of the Choice of the Texts The three authors (in the order of the publication years of the three selected texts by them) came respectively from North America (United States), South America (Argentine), and Europe (Britain), the three major continents (as well as countries) of the western world, which makes the research on the modern “western” fictions representative in a balanced way. The three texts are written respectively in the early twentieth century (1905), mid-twentieth century (1970), and late twentieth century (1989), which reflects a general western rewriting tradition throughout the twentieth century. The sources of these three rewrites, as well as their ways of rewriting, are different. Twain’s Diaries and Barnes’ History rewrite two different stories in the Old Testament, while Borges’ “Gospel” rewrites one in the New Testament. Mark Twain used the story of Adam and Eve to construct the whole novella, while Julian Barnes - 28 - 复旦大学 论文集(2007) used Noah’s Ark only as some sort of prologue to introduce his writings. The three texts, as well as their authors, were all well-known in their own age and after. All the three authors are well educated, and have achieved their literary success world-wide, and therefore represent the elitist culture. Their achievements are the focus of this research, and the three rewrites will be studied in terms of their production, their publication, readers’ reception, as well as the interactive relationship between the previous three elements. Chapter 2 Biblical Allusions? But Why? 2.1 The Diaries of Adam and Eve This book title has a clear indication to the archetypal characters in the Holy Bible. Mark Twain, the famous American humorist, picked up the story of the first couple in the world, and rewrote their story in his characteristically humorous tone. The most obvious example comes in his retelling of the story of Abel and Cain. The Bible says that Cain, a tiller of the ground, and Abel, a keeper of sheep, were both children of Adam and Eve. They both gave offering to the Lord, who, however, favored only Abel and his offering. The enraged Cain therefore killed his brother, Abel. (Gen. 4.1-8) Twain comments on this event, in the voice of Adam, with a single sentence, “Abel is a good boy, but if Cain had stayed a bear1 it would have improved him.” (18) He implies that if Cain had not grown up, he would not have killed his brother. In this way, he teases the basic Christian tenet. Despite such literal “disrespects” to the holy book, Twain’s intention of writing this book is not to express his dissatisfaction with Christianity. He wrote this book more as a love story, because he was personally enchanted with the story of the first couple in the world. Besides this book, he also wrote several other related stories, including That Day in Eden, Eve Speaks, Adam’s Soliloquy, A Monument to Adam, etc. Twain wrote this book as an affectionate tribute to his recently deceased wife, Olivia Langdon, who passed away one year before the book was finished. At the end of Eve’s Diary, Twain says, from the mouth of Eve, that “It is my prayer, it is my longing, that we may pass from this life together …. But if one of us must go first, it is my prayer that it shall be I; for he is strong, I am weak, I am not so necessary to him as he is to me – life without him 1 As the story goes, when Adam and Eve first saw the baby, who walked with four legs, they did not know that this was their child. They thought this might be a bear. So when Adam said “if Cain had stayed a bear”, he meant “if he had not grown up”. - 29 - 现代西方小说中改写经典文学的现象与问题分析 would not be life.” (40) On the surface, these words seem to be a woman’s tribute to a man, yet when you discover that they actually come from a man, you will immediately realize that they are actually a man’s comprehension of the unfailing love of his wife. Twain concludes the story with Adam standing at Eve’s grave, saying, “Wheresoever she was, there was Eden.” (40) This is what Adam says of Eve, and moreover, what Twain said of his wife. 2.2 “The Gospel According to Mark” This short story employs the same title of the second book in the New Testament. Unlike Twain’s Diaries, this short story does not employ the biblical character, Jesus, as the protagonist. But for the title, the relationship between this story and the Bible may be too implicit to discover. Borges did not borrow the characters, or the events with ease. Instead, he took the frame structure of the gospel of Mark, and filled in his own elements to show his reflections on certain problems. The gospel of Mark in the Bible relates the story of Jesus. It has two main themes, the first of which is the preaching and miracles of Jesus, and the second is his crucifixion and resurrection. In Borges’ “Gospel”, the experience of Espinosa, the protagonist, resembled to that of Jesus. Although he was not consciously preaching, his reading of Mark’s gospel to the Gutres as an exercise in translation had practically made him a preacher in front of the Gutres. Besides, after he stopped the bleeding of the girl’s lamb with some pills, the uncivilized Gutres thought this was a miracle, and considered Espinosa almost as powerful as Jesus. From then on, their attitude toward Espinosa totally changed. His “timid orders” “were immediately obeyed” (170). Moreover, the Gutres “liked following him from room to room and along the gallery that ran around the house” (170), just as the believers who followed Jesus. After listening to Espinosa’s “preaching”, however, the Gutres, who seemed to have understood what he had read to them word for word, imitated the sacred texts and crucified him. They “mocked at him, spat on him, and shoved him toward the back part of the house” (171), which reminds the readers immediately of the soldiers who mocked Jesus in the Bible (cf. Mark. 15.19). Such implicit allusions to the Holy Bible are everywhere to be found in the novel. With these allusions, Borges questions the formation of ideology, and, to some extent, religion’s influence on people. Unlike Twain’s humor, Borges’ way of questioning is “irony”. How the Gutres - 30 - 复旦大学 论文集(2007) became faithful in the doctrines of Christianity, and how they understood the doctrines are the two most important ironies on the thematic level. The Gutres were preached to believe in the Bible by a “freethinker”, “whose theology was rather dim”, and who only “felt committed to what he read to the Gutres”. Moreover, they believed in these doctrines only to the extent that they thought the behaviors in the Book could and should be imitated, so they crucified Espinosa in the hope of being rescued from the devastating storm. After “the new storm had broken out on a Tuesday” (170), they pulled down the beams from the roof of the shed, which were supposed to protect them from the storm, to make the cross (171). Their idea that the crucifixion of Espinosa, instead of a safe shed, was able to rescue them from the storm, is exactly where the irony lies. 2.3 A History of the World in 10½ Chapters Compared with the previous two narratives, Barnes’ is more complex and multiangular. This novel is not about the Bible; nor is it about religion, to be strict. It is more, as its title suggests, about “history”. In the flow of Barnes’ retelling the biblical story of the Flood, he is writing his version of “history”, which is somewhat different from the biblical history. For example, when it comes to the three sons of Noah, the Bible tells us that “Noah had three sons, Shem, Ham, and Japheth” (Gen. 6.10). However, according to Barnes’ History, he had another son, Varadi, who was not mentioned in any history books. Barnes says that Varadi, the youngest and strongest of Noah’s sons, and his ship “had vanished from the horizon, taking with it one fifth of the animal kingdom” (5-6). Whether Varadi really existed or not is not the concern of Barnes. His concern is on the relationship between “history” and “reality”. He further develops this view in later chapters, “History isn’t what happened. History is just what historians tell us. There was a pattern, a plan, a movement, expansion, the march of democracy; it is a tapestry, a flow of events, a complex narrative, connected, explicable. One good story leads to another.” (240) His view of history is clearly revealed in these sentences. He points out the difference between “history” and “reality”, with the story in the Bible as a prologue, and more other stories that follow. Chapter 3 Rewriting the Bible: A Canonization of Literary Fictions - 31 - 现代西方小说中改写经典文学的现象与问题分析 The criteria of canons are long under discussion. And the most controversial problem is “Whose canon it is?” Since the process of canonization is more or less influenced by some authoritative powers, canons inevitably reflect the values of those powers. For example, in medieval Europe, the choice of canons is greatly influenced by the power of courts and the power of churches. The authority of these canons relied much on the powers that supported them. However, in modern times, the authority of the powers of schools, of courts, and of churches is greatly challenged. And with the rise of western Marxism and the theory of cultural production, literary works are taken as cultural products, and therefore follow the principles of markets. As a result, the choice of canons goes into the hand of the producers, the consumers and the spreaders of these literary products. In the modern process of canonization, there are four elements that influence authors’ creation of works and their reception: the publishers, the readers, the critics, and the social environment. Of these four elements, the first three interact with the works (and the authors), and meanwhile they interact with each other. The last element influences all the above elements, including the works (and the authors). In order to make the above mode more understandable, I make the following graph. Readers Works (Authors) Publishers Critics Social Environment Then I will explain in detail this mode, and apply it to the reception of the three fictions within discussion. 3.1 The Influence of Publishers on the Reception of the Works The publishers may be one of the most important elements in the reception of the works, since it is they who make the works available to the readers. They are specialists in knowing what kind of books is most likely to be accepted and liked by the readers (or the market). They represent, to some extent, the taste of the mass. The authors of the three narratives are all well-recognized writers. The publishers - 32 - 复旦大学 论文集(2007) have published many of their works, which are nearly all among the bestsellers. So the publishers are more confident in their works, and are therefore more willing to publish them. In this case, there is very much likely to be a Matthew Effect (i.e. the famous writers will have more chances to publish more popular books, which make them even more famous; while the less famous writers will lose more chances to become famous). However, the choice of the publishers is based on economic concerns. Their objective is to make more money with these books. Therefore they put little emphasis on the instructive function when they choose the canons. 3.2 The Influence of Readers on the Reception of the Works The readers are the recipients of the work, and are therefore an important element in the process of canonization. It seems impossible to canonize a work which the readers do not like. But what are the criteria of readers in choosing what books they like to read? Literature, as a form of art which is different from other products, should meet the aesthetic needs of readers. Generally speaking, literary canons should be written in good language with outstanding writing skills. The three authors discussed above are all well-educated, which ensures that their works are mostly of high quality. This is a fundamental qualification of their success. However, good master of language and excellent writing techniques are not the only concerns of the readers, if not the least important ones. We have found enough modern works that are written in plain language, but still intoxicate the readers. In addition to the aesthetic concerns, readers also have a concern of the emotions that are shared between them and the works (or the authors). This emotion may also be one that is shared among all human beings. The most obvious example lies in the success of Twain’s Diaries. The love between Adam and Eve arouses sympathy in the heart of the readers. This common emotion that is expressed by Twain in memory of his deceased wife, is shared not only between the readers and Twain, but among all the people who desire to love and to be loved. Readers’ likes may not be sufficient for canonization, but at least a work without readers’ likes is even less likely to be canonized. Western people’s familiarity with the Bible makes the three fictions more approachable and appealing to the readers. They share more easily with what the authors intend to express. If Twain had told the same love story, but without Adam and Eve as protagonists, this novella might not have been so successful. If Barnes had not begun his novel with a period of history that is less familiar to the readers, they might be difficult to share Barnes’ view of history. - 33 - 现代西方小说中改写经典文学的现象与问题分析 3.3 The Influence of Critics on the Reception of the Works A critic is, first of all, a reader. Yet, he is different from a reader in that he is, to some extent, more knowledgeable than ordinary readers. The knowledge empowers him to canonize works. The critics may help the ordinary readers to understand and appreciate the works of some so-called “elite” writers. For example, since Barnes has a strong educational background in modern languages and literature, his novels usually contain lots of allusions, and are hard to understand for ordinary readers. Critics play an important role in making his works known to the readers. However, the knowledge of critics is a two-edged knife. It brings the critics superiority above the readers, and meanwhile, it alienates them more or less from ordinary readers. Their choice of canons may be too specialized. 3.4 The Influence of Authors’ Works on Publishers, Readers and Critics Since one important function of canon is instruction, the publishers, the readers, and the critics are all likely to be instructed by the works (and the authors). And one of the motives why authors write the works is to communicate their values to the outside world with intention to change the values of others. By such means they influence the reception of his works. That’s why the three elements and the works are interacted. Barnes, for example, tends to communicate his view of history with the outside world, and convince others of his view. With his efforts, people’s view of history may change gradually. 3.5 The Interactions between Publishers, Readers and Critics The publishers influence the reading of readers by deciding what books are available to them, and are influenced meanwhile by the readers in meeting their taste, if they want to make more money on them. The critics influence, and are influenced by both the publishers and the readers. It is a force between the other two: by criticizing, the critics infuse the ideology they think a society should hold onto the publishers and the readers, intending to normalize their thinking and behaviors; on the other hand, since their act of criticizing is passive (i.e. they can only criticize what the publishers have published and have made available to the readers), their criticizing is limited within publishers’ economic concerns and readers’ likes. Therefore, the process of modern canonization is a process that involves different forces, and it is a process of the interaction of these forces. - 34 - 复旦大学 论文集(2007) 3.6 The Influence of Social Environment Above all these forces, there is the social environment that influences all the previous interactions. The social environment is a relatively ambiguous concept. It includes the social ideology, the political power, the religious belief, and all alike. It may not be as detectable as the other forces. It influences the canonization subtly yet fundamentally. For example, Nicos Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation of Christ, also rewriting the biblical story of Jesus’ crucifixion, yet not as lucky as Borges’ “Gospel”, was banned from publication for religious reasons. It may be popular, since it has been adapted into movies, but it can never be canonized (at least, it seems so now). The reason why the two works rewriting the same biblical story have different fates is just because of the social environment. Borges’ “Gospel”, although questioning on the formation of religious belief, does not violate the basic Christian tenets. In contrast, Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation of Christ, which tells a story of Jesus not resisting the temptation before crucifixion, and betraying God, seriously challenges the fundamentals of Christianity, and is banned from publication. Therefore, the social environment plays an important role in canonization. Chapter 4 Conclusion As a conclusion to the above discussion, a canonical work of modern times usually has three criteria. The first criterion is its excellence. Although the canonical work may not be the best of all works, it is by no means among the worst. Each of the above four forces (authors, publishers, readers, critics) makes efforts to ensure that the works are of high quality, and have high values. These values may be the artistic value, or the ideological value. Whatever these values are, canonical works should maintain a high quality. The next criterion is the reception of the readers. A canonical work of modern times, before being tested by time, should first be accepted by the mass readers. The last criterion is the uniqueness and originality of the work. By “originality”, I do not mean a total overthrow of traditions. Since total new creations are no easier for readers to accept, not to say canonizing, re-creation within certain models is usually a “safe” way of writing. That is the reason why the three rewrites are successful. They have borrowed the familiar story structures from the Bible, and put in their original ideas, which makes their works popular among the readers. - 35 - 现代西方小说中改写经典文学的现象与问题分析 Works Cited Abrams, M.H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. 7th ed. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2004. Baldwin, Elaine, et al. Introducing Cultural Studies. Beijing: Peking University Press, 2005. Barnes, Julian. A History of the World in 10½ Chapters. New York: Vintage Books, 1989. Borges, Jorge Luis. “The Gospel According to Mark.” Trans. Norman Thomas di Giovanni. An Introduction to Fiction. Eds. X. J. Kennedy, and Dana Gioia. New York: Longman, 1996, 167-171. Bourdieu, Pierre. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. Ed. Randal Johnson. New York: Columbia University Press; Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993. Culler, Jonathan D. Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. Holy Bible: The King James Version. New York: New York Bible Society, 1611. Kristeva, Julia. Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art. New York: Columbia University Press, 1980. LeMaster, J. R., and James D. Wilson, ed. The Mark Twain Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Pub, 1993. Lentricchia, Frank, and Thomas McLaughlin, ed. Critical Terms for Literary Study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995. Lindstrom, Naomi. Jorge Luis Borges: a Study of the Short Fiction. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1990. Paine, Albert Bigelow. Mark Twain: a Biography: the Personal and Literary Life of Samuel Langhorne Clemens. 2 vols. New York: Harper & Bros., 1912. Twain, Mark. Chapters from My Autobiography. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. Twain, Mark. The Diary of Adam and Eve. London: Hesperus Press, 2002. Williams, Raymond. Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977. Acknowledgements Firstly, I am grateful to the Chun-Tsung Undergraduate Research Endowment for its support of this research. And I am particularly thankful to Professor Tsung-Dao Lee, who has established this endowment as an expression of affection to his deceased wife, Hui-Chun Chin. Secondly, I want to deliver my gratitude to my advisor, Professor Li’an Lu, for her instruction during this whole year. Last but not least, I want to thank all my lovely friends for their constant support and help in the past year. - 36 -