The Crucible—Arthur Miller.doc

advertisement

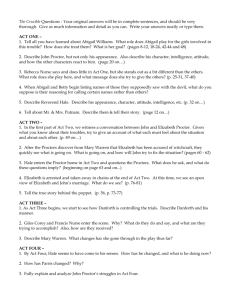

The Crucible—Arthur Miller Plot Summary— 1. Reverend Parris sees Abigail and a group of other girls dancing in the forest with Tituba, a black salve. They all appear to be performing some kind of satanic ritual. 2. Betty, Paris’s daughter, fall ill and Abigail denies doing anything other than “dancing.” 3. The audience learns of John Proctor’s previous affair with Abigail, which led to Abigail getting fired by John’s wife Elizabeth. 4. Proctor refuses to continue his relationship with Abigail although Abigail still desires him. 5. Paris and Hale interrogate Abigail. Tituba ultimately admits to “trafficking with the devil” and suddenly hysterically accusing certain townsmen of witchcraft. Abigail and Betty join in and soon the hole ton is in obsessed over the idea of the possibility of an evil conspiracy. 6. Elizabeth demands that Proctor denounce Abigail for a fraud and he refuses; Elizabeth becomes angry, believing that Proctor is continuing his relationship with Abigail. Mary Warren alerts Elizabeth that she has been accused of witchcraft. 7. Mr. Hale enters and questions Proctor, asking him to recite the Ten Commandments of the Bible. Ironically Proctor forgets the commandment warning against the sin of adultery. 8. Elizabeth is arrested. 9. Proctor demands that Mary Warren tel the court the truth about Abigail’s lies. 10. Marry testifies against Abigail but when the girls are brought in for questioning, all o them claim that Mary Warren has “bewitched them.” 11. Proctor confesses about his affair with Abigail and claims that Abigail’s sole motive is out of jealously of his wife. 12. The judge calls in Elizabeth to question her about Proctor’s affair with Abigail. Elizabeth lies in court to protect John. 13. The judge denounces Proctor as a liar while the girls pretend that Mary Warren is “bewitching” them. 14. Proctor rages against the court and is arrested for his conduct. 15. As time passes and summer fades into autumn, the witch trials have stirred unrest in neighboring villages. The judge Danforth becomes uncomfortable with the situation. Abigail runs away, taking all of Paris’s money with her. Hale, having lost faith in the court, begs those accused of witchcraft to confess. 16. Proctor refuses to confess or incriminate anyone else. When Proctor verbally confesses, the courts demand that he make a written public confession. This angers Proctor and he rips up the confession. 17. Proctor and the others are led away to the gallows to hang. Characters— John Proctor—sinful and stubborn; has a short romantic relationship with the younger Abigail Williams. The protagonist of the play; struggles with his conscience throughout the course of the play. Chooses to die rather than to give the church a false confession and condemn other innocent people. “we are only what we always were…only naked.” Elizabeth—Proctor’s wife. Forgives John after she finds out that he has been unfaithful to her. When Hale implores her to speak out in order to save Proctor form being executed she refuses in her declaration: “he hath his goodness now. God forbid I take it form him!” Reverend Samuel Parris—a widowed religious fanatic who becomes easily obsessed with the persecution of witches. Paris believes that he has a reputation to maintain. Mary Warren—John Proctor’s servant. Fails to successfully reveal the manipulation of Abigail’s character. Reverend Hale—a friend of Proctor’s. Ultimately believes that he john is not guilty of witchcraft; the first to see the witch trials for the abominations that were their true natures Tries to convince Proctor to confess in the end to save his life. Mrs. Putnam—her first seven babies died; claims that it was the work of evil and that witches sucked the life out of her children. Rebecca—old woman wrongfully accused of witchcraft. A devout Christian, Rebecca is usually silent and does not really protest when she is in jail. “…is Rebecca nurse be [found] tainted…the court will send her home…” (Hale’s view once he sees that Rebecca has been accused of witchcraft) Abigail—although her romantic tryst with Proctor last a short while, Abigail believes that she is John Proctor’s lover. Claiming to have the ability to sense evil spirits, Abigail is an abusive and defensive young lady. Exhibiting an “endless capacity for disassembling,” Abigail blames but her self for the tragic events that unravel around her. Seen dancing in the woods and drinking blood (performing some kind of satanic ritual) and yet she confesses to nothing Goody Proctor doesn’t come to church because she doesn’t want to be in the presence of Abigail whom she considers to be “something spoiled.” Setting— Beginning of the play to the end: morning dusk/night midday sunrise. Sunrise is representative of resurrection after death—dawn is the realization of the ludicrous of the Salem witch trials. Spring—time of hope and rebirth. Acts I and II. Fall/Autumn—a time of death and rotting. Acts III and IV. Court House—sun in the courtroom worldly justice and human salvation sun shines strong whereas the courtroom is cold (Abby claims) sunshine—shows how the world continues despite the horrors of the trial Jail Cell (Proctor)—usually no light, moonlight is representative of some form of hope; night stars=celestial/God Symbols— Golden Candlesticks—(pewter vs. gold)representation of the hypocrisy of the church. Pewter o molded with hands o closer to God/ personal religious connection o malleable Gold o Symbol of greater wealth in the church o Harsh and unyielding o Not easily tarnished—hiding the truth o Considered pure and yet the church is corrupt o Cannot have pure gold (not useful), must be mixed with something else (although it also becomes less pure) Ten Commandments—reveal the irony in Proctor’s adultery. The church test knowledge as akin to believing and following God (superficial/ ignorant justification for persecuting those suspected of witchcraft) The Crucible—the title itself is a symbol, extremely relevant to the entirety of the play. Metaphorically, a crucible is an extreme test of ability to endure pressure, darkness, and fire; a true test of one’s humanity. (a test of ability: right vs. wrong) Motifs— Night—under the cover of night, evil shows it s ugly face. Often associated with witchcraft, night is considered the “devil’s hour.” Injustice—throughout the play, the concept of injustice is a constant. As those who are corrupt would invoke the idea of justice (all in the name of self-preservation), the irony in the justice of man vs. the justice of God is revealed. Themes— On personal integrity… The strength of personal integrity is greater than that of society’s corrupt morals. On the true nature of evil… Arthur miller: “…the Devil is known to lure people into forgetting what it is vital for them to remember—how else could his endless reappearance always come as a surprise? ” On the choice between life and death… Death is better than a life of lies, plagued by a sinful past and a guilty conscience. Death—only God can judge Life—live (a lie) and be judged by one’s on insecurities and the ignorance of man’s superficial justice o Confession may save mortal life…but is that life worth living??—forced to live a lie Satisfies the corruption of man and at no expense to his ignorance Held accountable by guilty conscience (conscience = God-given) Literary Criticism1— The theater critic Robert A. Martin wrote in Modern Drama that The Crucible “has endured beyond the immediate events of its own time. If it was originally seen as a political allegory, it is presently seen by contemporary audiences almost entirely as a distinguished American play by an equally distinguished American playwright.” His comments are misleading because they imply that a play cannot be “distinguished” if it is also political. What Martin seems to be assuming is firstly that a play must, in some sense, be “timeless” in order to be “distinguished,” and secondly, that a political play is, by its nature, only relevant within a limited historical and social context. I would argue that Miller’s play is highly political, but that while it draws much of its impetus from a given historical situation — Joseph McCarthy’s war against communist Americans — it 1 Joanne Woolway is an educator affiliated with Oriel College in Oxford, England. In this essay she proposes that while Miller’s play was aimed at criticizing a specific period in American history — the McCarthy trials of the 1950s — the work has relevance to modern society on a number of levels, particularly the topic of child abuse. also raises political questions which are valid in a range of social, cultural, and historical contexts. The relevance of Miller’s themes to modern audiences has been emphasized by the 1996 film production of The Crucible, directed by Nicholas Hytner (The Madness of King George) and adapted by Miller himself. In his introduction to the published edition of that screenplay, Miller commented, “as we prepared to shoot the movie, we were struck time and again by its alarming topicality: it spoke directly about the bigotry of religious fundamentalists across the globe, about communities torn apart by accusations of child abuse, about the rigid intellectual orthodoxies of college campuses — there is no shortage of contemporary Salems ready to cry witchcraft. But the film’s political agenda is not specific. The Crucible has outlived Joe McCarthy, and has acquired a universal urgency shared only by stories that tap primal truths.” One of these areas — the topic of child abuse — particularly shows that Miller is keen to both root his writing in contemporary issues and at the same time challenge audiences by raising general questions about society, religion, and law. Miller made many changes, mainly structural, to his play text when he adapted it for film. But the changes he made to one scene in particular also suggest his concern to make the screenplay topical. In an episode which is not in the original play, Ruth Putnam accuses Jacobs of having sent his spirit into her room and says that it laid on top of her and pressed down on her: “He come through my window. . . . And then he lay down upon me . . . I could not take breath — his body crush heavy upon me. And he say in my ear, ‘Ruth Putnam, I will have your life if you testify against me in court.”’ Jacobs, taking her accusation more literally than it is intended, replies bemusedly, “Why, Your Honor, I must have these sticks to walk with, how may I come through a window.” The episode has undertones of child abuse — the accusation recalls recent cases in the U.S. and Britain where allegations of abuse have been made against members of a community which have later seemed to have been untrue. The play contains other elements which parallel these cases, particularly the scenes of collective hysteria, the speed with which gossip and rumors spread, and the inability of people to stop accusations once they have started. Miller’s concern in supplying these topical references is not to suggest that such child abuse does not occur, but rather to point to the circumstances in a society from which these false claims might arise. The society which is portrayed in The Crucible is one in which there is almost no outlet for creativity or imagination. Given this deficit, it is hardly surprising that the young women who gather in the woods to dance have strong imaginations which, when given any kind of outlet, take their imaginative stories to extremes and begin to believe — in one scene, for instance — that a large bird is indeed hovering in the roof of the courtroom. We know that their stories are fabrications, yet we can also appreciate that, to some extent, they believe what they are saying. The boundaries between fact and fiction are easily blurred when there are so few opportunities for expression. It is unclear at the beginning of the play as to the extent to which Betty Parris’s illness is feigned. So too in the scene of Ruth’s accusation in the film, the viewer’s perception of Ruth’s words lies within a grey area between an overactive imagination and a reality in which actual physical abuse may have occurred. This situation is similar to instances of mass delusion which are commonly identified in the behavior of religious cult members. Director Hytner pointed to one possible cause of this collective delusion in his introduction: female adolescent hysteria. As he explained, “we worked from the premise that the source of the girls’ destructive energy is their emergent sexuality, so the entire opening [with the girls ritually dancing around a fire] is designed to uncork the bottle of desire.” If we connect this emergent (and repressed) desire both to the excessively strict behavioral codes of Puritan religion in the seventeenth century and to the excessive demands of communities with extreme religious views, then the power of Miller’s topical references to raise issues beyond their immediate setting becomes clearer. The Crucible is an indictment of society’s attitudes towards religion and sexuality, I would argue, rather than an attempt to make a point about specific events in recent history. In Miller’s treatment of the character of Abigail, the distinction between individual malice and community disease is explained. The girl’s behavior indicates her mischievous enjoyment of the power that accusations against others bring. But the events her allegations set into motion go beyond mere mischief, suggesting that the community of Salem has embedded in its fabric elements of social corruption, moral disease, or unresolved and repressed feelings of anger and hostility; Abigail’s actions should be seen as a sign rather than a cause of these feelings. Because of her parents’ brutal murder, she is without adults to whom she is close: Reverend Parris cares for her material needs but there is no evidence that they are emotionally close. Her adulterous relationship with John Proctor and her alleged fate as a prostitute in Boston might be seen as a craving for affection which, in the absence of family love, manifests itself in physical desire. Her apparent belief in witchcraft may have similar roots — in a need to find an alternative to the strict and, it seems, loveless Puritanism of her uncle, which attracts her to precisely the things — black magic, physical expression, and sexual conjuring — which the religion of her community forbids. This commentary on collective guilt and responsibility adds further weight to Miller’s critique of societies which do not maintain a balance between individual liberty and social organization. In his prose insert before the beginning of Act One in the original play text, Miller notes that the aim of a theocracy such as that found in Salem is to “keep the community together, and to prevent any kind of disunity that might open it to destruction by material or ideological enemies. It was forged for a necessary purpose and accomplished that purpose. But all organization is and must be grounded on the idea of exclusion and prohibition. . . . Evidently the time came in New England when the repressions of order were heavier than seemed warranted by the dangers against which the order was organized. The witchhunt was a perverse manifestation of the panic which set in among classes when the balance began to turn toward greater individual freedom.” What Miller seems to be suggesting in both his play and screenplay is that examples of collective hysteria which lead to false accusations by a body of people who know those accusations to be untrue are not just examples of malicious slander but may also reveal deep-seated neuroses about sexual boundaries and individual freedoms caused by an excessive focus on prohibition and social acceptance. Where these fears cannot be expressed, and must instead be repressed, a perversion of normal social relations may occur. In the case of the Salem Witch Trials, Miller depicts this perversion in the form of extreme, and seemingly random, accusations against the ordinary people of a community. John Proctor sums up the suddenness and ease with which this corruption could be exposed when he cries out, “I’ll tell you what’s walking Salem — vengeance is walking Salem. We are what we always were in Salem, but now the little crazy children are jangling the keys of the kingdom, and common vengeance writes the law!” But this is a criticism which could be made of any society; Miller’s point is a timeless one, moving beyond the details of the Salem witch-hunts, and also beyond the topical allusions to cases of collective child abuse with which communities in the later twentieth century have become so involved. Whatever the historical context, both the play and film ask audiences to look inwards to the perversions, fears, and guilt which dominate their social and political life. In this sense, The Crucible is both timeless and deeply political. Source: Joanne Woolway, for Drama for Students, Gale, 1998. “MILLER’S PLAY RAISES POLITICAL QUESTIONS WHICH ARE VALID IN A RANGE OF SOCIAL, CULTURAL, AND HISTORICAL CONTEXTS.”