The Role of Virtual Communities as Shopping Reference Groups

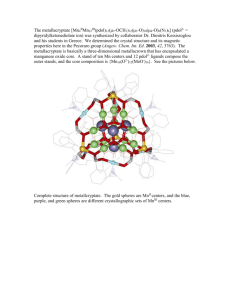

advertisement