Humanities 500 - College of Liberal Arts

advertisement

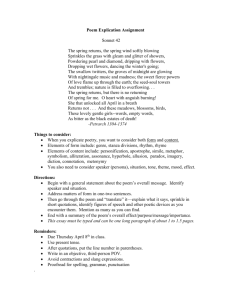

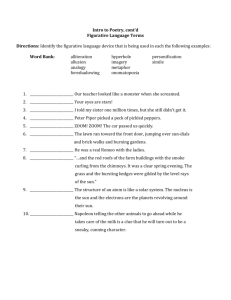

HUMA 500 – Critical Methods in the Humanities University of New Hampshire, Humanities Program, Fall 2010. Professor: Catherine Peebles Course meetings: TR, 2:10-3:30, Murkland Hall, room G16 Office hours: TR, 12:40 -2:00 p.m., and by appointment This course allows students to do extended, in-depth research on one topic throughout the semester. It is designed to help Humanities majors, European Cultural Studies majors, and university students in general master the art of serious paper-writing in the humanities. The Humanities Program also hopes that this course will prepare and encourage more liberal arts students to apply for UROP and IROP grants, which require the submission of a research proposal as part of the application process. Students write a final research paper of 15-20 pages. Before this, students will also produce an inclass presentation, an annotated bibliography, and a research proposal of five pages. There will also be two in-class exams on the course material, one toward the middle of the semester, and one toward the end. This course will address one main topic, and students will choose the focus of their research from an area within that general topic. For Fall 2010, the course topic is: Representing Desire. Reading List: All books are available at the Durham Book Exchange, on Main Street in Durham. It is important that you use the editions I have ordered. Other works (articles) will be available on Blackboard, and students must print these out, and bring them to class on the days we discuss them. Plato, Symposium. Sophocles, Oedipus the King Samuel Richardson, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded. Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice. Norton Critical Edition. MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, 7th edition. Bowlby, Rachel. “Family Realisms: Freud and Greek Tragedy.” Essays in Criticism, Volume 56, Number 2, April 2006, pp. 111-138. (to print out from Blackboard) Moon, Elaine B. “Richardson’s Pamela I.” Explicator, 1987 Winter; 45 (2): 18-20. (to print out from Blackboard) A note on academic honesty: I take the UNH Academic Honesty policy seriously, since trust is essential to any intellectual community, be it a whole college, a large course, or a small seminar. I refer any instance of academic dishonesty to the student's college dean and recommend dismissal from the university as the most appropriate penalty. Be sure you are familiar with UNH’s academic honesty policy, which you can reread in the Student Rights and Responsibilities handbook. You are responsible for knowing what plagiarism is, and making sure you do not commit it. If you have any doubts about what constitutes plagiarism, you may see the on-line tutorial at: http://www.unh.edu/liberalarts/plagiarism/plagiarismHome.cfm I do not allow students to use laptop computers during class, as it is distracting to both instructors and other students. Other electronic devices, such as cell phones, should of course be switched off and put away during class. A note for students with disabilities: If you think you have a disability requiring accommodations, you must register with Disability Services for Students (DSS). Contact DSS at 603.862.2607 or disability.office@unh.edu. If you have received Accommodation Letters for this course from DSS, please provide me with that information privately, during office hours, so that we can review those accommodations. Course Requirements: Coming to class prepared, having done the assigned reading and made extensive notes on it, and having carefully reviewed seminar notes. Students are expected and required to devote a minimum of six to eight hours per week to class preparation, which counts for 10% of the final grade. Preparing for this course involves reading and rereading the assigned work carefully, underlining important passages, making notes in the margins, and making notes in your notebook. Your own notes should range from copying significant sections of a text and definitions of new vocabulary words, to writing down specific questions you have, to formulating critical responses and interpretations. You are required to look up vocabulary words with which you are unfamiliar (the Oxford English Dictionary, which is available through the Library tab on Blackboard, is the best source). And you are required to bring formulated questions to each class meeting. Every student should also have prepared one passage from the text that she or he is ready to discuss through “close-reading.” This course is run as a seminar, which means that all of the participants are expected, equally, to contribute to our sessions. Your class preparation grade will be based upon your contribution of salient questions and interpretations, and your ability to respond cogently to questions concerning the assigned readings. Attendance is required. A student who misses three classes during the semester will lose a full letter grade for each subsequent absence, and is required to make an appointment and discuss the problem with her/his instructor. There is no distinction between “excused” or “unexcused” absences. The penalty scheme for attendance takes into consideration the occasional emergency or illness. Accordingly, students are allowed three absences with no penalty. After that, each absence lowers the grade by one letter-grade. Exams, proposal, research paper. There will be two exams during the semester. The exams will consist of essay questions, so that students will have the opportunity to demonstrate both their thorough knowledge of the texts and their understanding of the works’ themes and theoretical problems. The research proposal should be five pages in length, and should lay out the proposed thesis and structure of the paper. The accompanying annotated bibliography should include at least eight works: the primary text and at least seven secondary texts (books, book chapters, peerreviewed journal articles). For this course, students are required to find their secondary texts in books, book chapters, or peer-reviewed journals. Finally, the research paper is due on the last day of class. The paper should be 15 to 20 pages in length, and should treat extensively one major work from our syllabus. We will discuss students’ paper ideas in class; and students should bring up their concerns and ideas frequently, as this is the best way to begin making progress together. In addition to these assignments, beginning the week of November 2, each student will give one in-class presentation on work in progress, and these presentations should be devoted to a close reading of one significant passage in the work under consideration. The presentation should also tell us about one useful secondary source the student has found (including author, title, date, place of publication, thesis claim, and why it is of use for the student’s work). Students bring two copies of the presentation to class – handing in one, and reading from the other. The final grade for the course will be an average of the above components, as follows: Exam 1 Exam 2 Research proposal 15% 15% 15% presentation research paper class preparation 15% 30% 10% Reading Time-table T R Aug. 31 Sept. 2 Introduction to the course Plato, Symposium T R Sept. 7 Sept. 9 Plato, Symposium (close reading) Plato, Symposium (close reading) T R Sept. 14 Sept. 16 Plato, Symposium (close reading); Sophocles, Oedipus the King Sophocles, Oedipus the King T R Sept. 21 Sept. 23 Sophocles, Oedipus the King (close reading) Sophocles, Oedipus the King (close reading) T R Sept. 28 Sept. 30 Samuel Richardson, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded Samuel Richardson, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (close reading) T R Oct. 5 Oct. 7 Samuel Richardson, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (close reading) Samuel Richardson, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (close reading) T Oct. 12 R Oct. 14 Samuel Richardson, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded Discussion of article: “Richardson’s Pamela I” Samuel Richardson, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded Discussion of article: “Richardson’s Pamela I” Proposed paper topic due, including list of three secondary sources. T Oct. 19 R Oct. 21 T R Oct. 26 Oct. 28 Finishing discussion of Kant and the Enlightenment Mid-term exam (in-class, essay format) T R Nov. 2 Nov. 4 Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice By today: finish reading “Understanding the society in which Jane Austen sets Pride and Prejudice” (available to print on Blackboard) Research proposal due, including annotated bibliography T R Nov. 9 Nov. 11 Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice Discussing article: “Regulated Hatred” (available in your edition of P&P) T Nov. 16 R Nov. 18 Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice Discussing article: “The Humiliation of Elizabeth Bennet” Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice T Nov. 23 Immanuel Kant, “What Is Enlightenment?” and “Duties toward the Body in Respect of Sexual Impulse” (both available to print on Blackboard) Immanuel Kant, “What Is Enlightenment?” and “Duties toward the Body in Respect of Sexual Impulse” (both available to print on Blackboard) Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice. Final draft of research proposal due, including updated annotated bibliography. R Nov. 25 NO CLASS (Thanksgiving holiday) T Nov. 30 Sigmund Freud, from The Interpretation of Dreams (excerpt available to print on Blackboard) R Dec. 2 Sigmund Freud, from The Interpretation of Dreams, and “ ‘Civilized’ Sexual Morality and Modern Nervousness” (available to print on Blackboard) T R Dec. 7 Dec. 9 Sigmund Freud, “‘Civilized’ Sexual Morality and Modern Nervousness” Wrapping up. Final papers due. Take-home exam handed out. Exam due in the Blackboard “drop box” by noon on Monday, December 13. Reading List with publication information included. Plato, Symposium. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1989. Sophocles, Oedipus the King The Theban Plays Paperback: 430 pages Publisher: Penguin Classics; 1st edition (January 3, 2000) Language: English ISBN-10: 0140444254 ISBN-13: 978-0140444254 Samuel Richardson, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded. Paperback: 592 pages Publisher: Oxford University Press, USA (August 1, 2008) Language: English ISBN-10: 019953649X ISBN-13: 978-0199536498 Immanuel Kant, “What Is Enlightenment?” (available to print on Blackboard), and “Duties toward the Body in Respect of Sexual Impulse,” from Kant, Lectures on Ethics. London: Methuen, 1930. Reprinted in Robert Steward, ed., Philosophical Perspectives on Sex and Love (available to print on Blackboard). Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice. Norton Critical Edition. Paperback: 424 pages Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company; 3rd edition (September 2000) Language: English ISBN-10: 0393976041 ISBN-13: 978-0393976045 MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, 7th edition. Paperback: 292 pages Publisher: Modern Language Association of America; 7th edition (March 9, 2009) Language: English ISBN-10: 1603290249 ISBN-13: 978-1603290241 Bowlby, Rachel. “Family Realisms: Freud and Greek Tragedy.” Essays in Criticism, Volume 56, Number 2, April 2006, pp. 111-138. Moon, Elaine B. “Richardson’s Pamela I.” Explicator, 1987 Winter; 45 (2): 18-20. The following explanation of “close reading” is taken from Dennis Jerz’s “Intro to Literary Studies” webpage (http://jerz.setonhill.edu/EL150/2008/close_reading.php) Close Reading A close reading is a careful, thorough, sustained examination of the words that make up a text. You "read closely" in order to focus your attention on the actual words contained in the text. A close reading uses short quotations (a few words or only one word) inside sentences that make an argument about the work itself (rather than an argument about your reactions, incidents in the author's life, or whether things today are different from or similar to the society depicted in the literary work). Note: Close reading is always re-reading. In a close reading, a text is not so much a mirror to reflect your own opinions and personal reactions; nor is it a window, to look through in order to learn about the subject of the text or the author's motivations or goals; rather, you look at the glass itself -- you look at the language, grammar, punctuation, structure, with the understanding that the author chose each word, each line break, each allusion, in order to achieve a certain effect. Rather than imagining or arguing about what the author intended, a close reading examines what the text itself has accomplished. Example: "Trees," Joyce Kilmer (1919) I THINK that I shall never see A poem lovely as a tree. A tree whose hungry mouth is prest Against the sweet earth's flowing breast; A tree that looks at God all day, And lifts her leafy arms to pray; 5 A tree that may in summer wear A nest of robins in her hair; Upon whose bosom snow has lain; Who intimately lives with rain. Poems are made by fools like me, But only God can make a tree. 10 How to Read a Text Closely 1. You will probably want to read your text once through fairly quickly, highlighting unfamiliar words or puzzling details (or marking them with sticky notes, if you're reading a library book). 2. Go back and look more carefully at the places you marked. Did the ending explain some of the things you initially found puzzling? Do you see any recurring patterns? 3. Once you have a sense of what you think is important, go through the text again, this time searching specifically for more of whatever caught your eye. 4. Once you have identified the details that you find interesting, you should come up with a thesis -- a non-obvious claim, supported with direct quotations from the material you are studying. (It is not enough merely to write down a list of isolated observations, in the order they popped into your head.) When you write a close reading, you should assume that your reader is not only familiar with the text you are examining, but has a copy of it within reach. (It is fine to type the quote you plan to use at the top of your paper, but that quote won't count in terms of page length or word count.) A close reading does not retell the plot. Neither should a close reading profile the characters give advice to the author speculate on which people or events in the author's life inspired the literary work list reactions that popped into your head while you were reading compare the society depicted in the story to your own compare the choices and values of the narrator to your own A close reading does not use a literary work as a handy example to support general claims about the outside world (such as "racism is bad" or "women have come a long way" -- statements that would be true or false regardless of whether someone had written a poem on a related theme). This poem talks about the beauty of trees, and how a tree is a living thing that drinks from the breast of the earth, prays to God, is a home for the birds, relates to the weather in various ways, and is made by God. The above simply summarizes the content of the poem, without offering any analysis. The summary only focuses on the description of the tree, without addressing the purpose of that description -- comparing the poet's implied failure at creating a lovely poem with God's success in creating lovely trees. No poem worth the effort simply "talks about" anything. If you find yourself writing "In this poem, the author talks about" or "In this paper, I will talk about," your spidersense should tingle. A poem should generate new thoughts in the mind of the reader, and the poet has carefully crafted the work with specific effects in mind. A close reading involves detective work. We need to count footprints, dust for fingerprints, and map out the scene in order to understand exactly how the poem achieves what it does. I like this poem because it makes you think of a tree as a person. With the Earth's natural resources threatened by the unchecked advance of civilization into what was once pristine nature, Kilmer's "Trees" is important because it forces us to think about our relationship to trees. Listing your reasons for liking a poem is not part of a close reading. The statements about the rainforest and civilization would be true regardless even if Kilmer had never written this poem, and he probably was not thinking about global deforestation when he wrote it almost a hundred years ago. If you were looking for a poem to put on the inside cover on a pamphlet promoting an ecological conference, then you might very well need to analyze several different poems in order to find the one that has an ecological message that meshes well with the theme of the conference. Likewise if you were searching for a poem to honor the achievements of women, or to make a statement about war, or you were trying to find a love poem to recite for your sweetheart on Valentine's Day, your close reading skills can help you find the right poem. However, in the English classroom, being able to identify the argument a poem makes, and coming up with ways to make use of that argument in the real world, falls under the very basic skills of summary (restating the poem's content) and application (making it useful in your life). A good close reading sticks to the world that is being represented in the literary work, not the world that you already knew before you ever read the poem. In "Trees," Kilmer uses personification to bring the reader into close, personal contact with nature. At first the tree is a conventionally "lovely" object for aesthetic contemplation, but the following stanzas each present the tree as an active participant in a series of relationships. The personified "hungry mouth" of the tree and the "sweet earth's flowing breast" both invoke the strong emotional bond between the mother and infant. Likewise, the tree's "leafy arms" are not merely a static metaphor that compares a branch to a human limb; rather, in this poem we see the branches as actively engaged in a relationship. The tree "looks at God" and "raises" her branches "to pray." The "nest of robins" invokes the image of birds caring for their young, which echoes the relationship between the tree and mother Earth; but this stanza also introduces the idea that the tree is also a source of protection for weaker creatures. This stanza turns out to be an important transition, because in the previous relationships (with the earth and with God), the tree is in the subordinate position. Now that Kilmer has asked us to consider the tree in an adult role, as a woman dressing up in order to provide for a surrogate family, we see he has provided the tree with a "bosom" on which "snow has lain," and we learn the tree "intimately lives with rain." In keeping with the mores of the time, the language is discreet, but the sexualized imagery is unmistakable. The final statement that "only God can make a tree" affirms the goodness and virtue of the natural progression through the stages of infant, supplicant, provider, and lover. The above example uses brief quotations from the text, in order to look closely at what the text does. Note that the acceptable revision can still offer a pro-environmental message, but the focus in the above passage is on the poem itself, and on the world represented by the poem. Is this the only acceptable meaning that one can get out of this poem? Of course not. Kilmer's use of feminized language to describe the natural world illustrates the sexist strategies of conventional nature poetry. Kilmer introduces the tree as a "lovely" passive object presented for the reader's approval, valuing it not for its height, its strength, or its ability to produce seed (which would be conventionally masculine values). Instead, the poem emphasizes the tree's decorative function, reducing its natural role as a habit for birds to a hairdo that makes a summertime fashion statement. By supplying the tree with a "bosom," Kilmer chooses a loaded word to sexualize the tree's physical relationship with "snow." Likewise, by likening her method of accessing water to a mistress who "intimately lives with" whoever provides for her needs, the poet sexualizes and commercializes a transaction over which the tree (in its natural role as a plant and its metaphorical role as a woman) can exert no free will. In the final couplet, which compares poetry with trees, and "God" with "fools like me," the poet somewhat arrogantly aligns himself with God. While the text of the poem suggests that the poet's ability to create poems cannot compare with God's ability to create trees, the subtext of the poem (the fact that this particular poem uses language in order to feminize those trees -- while placing them firmly under God's control) illustrates the poem's subtle confirmation of a male-dominated world view. Note that the last two examples make diametrically opposed claims about the same work, yet I have marked them both with a green check. Both examples effectively demonstrate the use of close reading skills. Reality check. Do I really believe that "Trees" is male-chauvinist propaganda? No, but my close reading makes a good case for it nevertheless. A weakness of this argument is that the masculinized rain and snow have no agency either, so it's a bit of a stretch to suggest that the snow and rain are taking advantage of the tree's need for water. Kilmer was a male born during a period of transition between the 19th and 20th centuries, so it's not really productive, from a literary standpoint, to go hunting for evidence that his values don't perfectly match what is considered politically correct in the 21st century.