Although Ulysses is now considered to be one of the greatest novels

advertisement

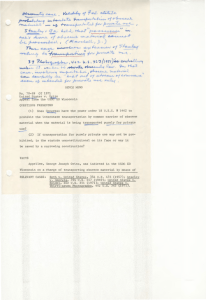

Introduction Throughout history, books have typically been banned for one of three primary reasons: sedition, heresy, and obscenity. The first two reasons are far more common than the third in most societies, but the United States is somewhat unique in that the First Amendment to the Constitution has always protected speech that some consider heretical. Although the U.S. Congress passed laws banning seditious speech in 1798 and 1918, these laws were short-lived, and no major book bannings occurred as a result. However, many books have been legally banned in the U.S. for obscenity, the definition of which has been the subject of great debate in the judicial system for more than a century. The sale of obscene material was banned in most U.S. states from the early 1800s, but the first national law prohibiting the distribution of such materials was the Comstock Act of 1873. At the time it was enacted, the Comstock Act applied to many kinds of materials, including contraceptive devices, but one of its primary effects was to stop the sale of “obscene, lewd, and/or lascivious” books. The federal Comstock Act applied only to the distribution of prohibited material through the mail, but this was the primary vehicle for the sale of books from publishers to wholesalers to bookstores. Additionally, many states adopted laws modeled on the Comstock Act to ban the sale of such materials within their borders. The Tariff Act of 1930 added another federal mechanism for banning obscene material, giving the U.S. Customs Department the authority to seize and destroy such works upon importation. The courts have adopted various standards over the years for determining whether published material is obscene. The Hicklin test was used in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This rule was borrowed from the outcome of the British case, Queen v. Hicklin, which determined that obscenity is defined as the tendency “to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences, and into whose hands a publication… may fall.” In the 1930s, the Hicklin test was modified by what is known as the “book as a whole” test, which makes allowances for literary merit and asks whether a work’s overall effect is pornographic in nature. In 1957, the Supreme Court set the obscenity bar higher, in the decision for Roth v. United States. The Roth test was “whether to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to prurient interest.” The Roth Opinion also states that obscenity is “utterly without redeeming social importance.” The Roth test was upheld in Miller v. California in 1973, but the Supreme Court Opinion added that the work must depict or describe “in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct,” and must “as a whole, [lack] serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” The Miller test is still used by the U.S. judicial system. At the center of these court decisions, the merits of some of the greatest and most popular novels have been debated. As literary authors have continued to push the boundaries of what is deemed acceptable, community standards have changed, making the banning of books under the terms of the Comstock Act nearly impossible today. Ulysses Ulysses is now considered to be one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century and a paragon of the Modernist style, but its initial publication in the United States was fraught with controversy. The novel was originally published serially in the literary magazine The Little Review between 1918 and 1920. Groups of concerned citizens objected to the explicit sexual content of certain episodes in the text, and the courts determined that Ulysses was obscene and could therefore be banned under the terms of the Comstock Act. When the novel was published in its entirety in 1922 by Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare Head Press in Paris, its importation into the United States was blocked, and 500 copies of the novel were destroyed by the U.S. Department of the Post Office. In 1930, the U.S. Customs Department declared that Ulysses was obscene and its importation could be banned under the Tariff Act of 1930. The publisher Random House took that opportunity to request a court hearing, which was required by tariff law. In the resulting case, United States v. One Book Entitled “Ulysses,” Random House argued that the explicit language and imagery must be viewed in the context of the book as a whole. Judge John M. Woolsey of the Federal Court of New York agreed, stating that the book was not pornographic in its overall effect. His decision was later upheld in the circuit court of appeals. The decision in the Ulysses trial set precedence for the obscenity standard to apply to entire works, rather than selected passages. Lady Chatterley’s Lover When D.H. Lawrence published Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1928, he expected that the book would be widely banned for sexual content and profanity, and thus elected to have 1,000 copies of the book printed privately in Italy. The novel caused a sensation among readers, and high demand led to the creation of dozens of pirated editions in the following years. Because of the unusual method of publication, Lawrence did not hold an international copyright for Lady Chatterley’s Lover, so he had little recourse for the fact that he received no money from the sale of the pirated books. The United States declared the book to be obscene in 1929, and many copies were seized in the mail or at Customs. Booksellers who attempted to offer copies of the novel were actively prosecuted throughout the country. In 1959, Grove Press challenged the ban by publishing an unexpurgated edition of the novel with the intent to distribute it in the United States. The Grove edition was immediately banned by Postmaster General Christenberry, which resulted in the trial Grove Press v. Christenberry. The ban on the novel was lifted in federal district court; Judge Frederick van Pelt Bryan argued that community standards of the time allowed for broader freedom of expression in dealing with issues of sexuality. The decision was upheld on appeal, but copies of the novel continued to be suppressed in the mail and in individual communities for many years. Tropic of Cancer Tropic of Cancer was originally published in Paris in 1934 by Obelisk Press, and was banned in the United States until Lady Chatterley’s Lover was determined not to be obscene. At that time, the Post Office and Customs lifted their bans, assuming that Tropic of Cancer would also be deemed acceptable in terms of community standards. Grove Press quickly brought out an American paperback edition of Tropic of Cancer in 1961. The appearance of a paperback edition of a book on which the ban had only recently been lifted caused an uproar in many communities. Because paperback editions are cheaper, they circulate more broadly, which caused concern that the corrupting influence of the novel might become more pervasive. Police in Chicago and other cities confiscated the books or attempted to intimidate booksellers to convince them to stop selling the novel. The result of these local actions was to force Grove Press to defend Tropic of Cancer in numerous lower courts, where no national determination of the book’s status as obscene or not could be made. Tropic of Cancer was defended for its literary merit by many leading scholars in the lower courts. Opponents of the book argued that the opinions of intellectuals did not consist of a “community standard,” and that the average person would react to the novel as pornography. However, one of the cases, Grove Press, Inc. v. Gerstein, eventually came before the U.S. Supreme Court, which declared that the book was not obscene using the Roth standard. Fanny Hill Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, or Fanny Hill, was written by John Cleland in 1748. It was banned in England in 1749, and Cleland was forced to renounce the novel. However, the book was very popular, and pirated editions were almost continuously produced and circulated. G. P. Putnam’s Sons published the first official American edition in 1963. It was immediately banned for obscenity. Fanny Hill is an erotic novel that has an overall effect of appealing to prurient interest. It is a popular work that is not seen as having the same literary merit as Ulysses and Tropic of Cancer. Therefore, it was not clear that it would fail the Roth test for obscenity. However, Putnam, a large and well-respected popular publisher, challenged the ban in court. In Memoirs v. Massachusetts, Putnam’s lawyers argued that while the novel does “appeal to prurient interest,” its enduring popularity upheld its social value, as determined by community standards. In 1966, the Supreme Court repealed the ban on Fanny Hill. After that decision, it became exceedingly difficult for literary works to be banned as obscene. The Catcher in the Rye Although The Catcher in the Rye has never been legally banned by a United States federal government agency, it has been the source numerous challenges in schools, libraries, and communities throughout the country. The reason for controversy is the novel’s common position as required or suggested reading for high school students. Since its publication in 1951, many concerned parents and allied organizations have objected to the novel’s moral ambiguity and profanity. However, schools, libraries, and teachers have staunchly defended the book as a well-written and thought-provoking novel, appropriate for literary education at the high school level. The continuing controversy surrounding The Catcher in the Rye exemplifies the typical methods by which books are currently suppressed in the United States. Rather than challenging the book for obscenity in federal courts, those who would have the book banned have done so at the local level, bringing their objections to school boards and library directors. This is an effective method, as school boards do not have to apply precedented obscenity tests to the materials they ban, nor are their decisions usually subject to judicial review. The Catcher in the Rye has consistently been one of the most frequently banned books in U.S. schools. In 1960, a high school English teacher in Tulsa, Oklahoma was fired for assigning the book to students, but was later reinstated after appeal. However, the ban on The Catcher in the Rye in the school continued. Such compromises are a common response to challenged books. While a school district may allow their libraries to retain copies of a challenged book, they will have it removed from all required reading lists. Another common compromise is to require parental permission for students to read a commonly challenged book.