US v. Orito

advertisement

I

s ~·-~'·""""·

"""""""' v

'

t ;j, ,~=--

~!"A~·

J...-t-

(

~-

~~ '""1.--:~~11.,;-~

"

~.......

c;..ct..

i ; , •. )

·;t~

L#lii!IO'IC-'

~r

-l

1../ b '7- fA .~ ' 'r. ~ /1 i11 )~ ~1-,.~t~"'-"~

~

'I

'f

t

·~""8,-IU'

I

,, ~

~~

BENCH MEMO

No. 70-69 OT 1971

United States v. Orito

Appeal !rom the U ~t ED Wisconsin

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

(1)

Does C~~~~ ss have the power under 18 U.S.C. § 1462 to

prohibit the interstate transportation by common carrier of obscene

-

material when the material is being transported purely for private

(2)

If transportation for purely private use may not be pro-

hibited, is the statute unconstitutional on its face or may it

be saved by a narrowing construction?

FACTS

Appellee, George Joseph Orito, was indicted in the USDC ED

Wisconsin on a charge of transporting obscene material by means of

RELEVANT CASES:

Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957); Stanley

v. Georgia, 394 U.S. 557 (1969); United States v.

Reidel, 402 U.S. 351 (1971); United States v.

Thirty-seven Photographs, 402 U.S. 363 (1971) .

. " ....

a common carrier in interstate traffic in violation of 18 U.S.C.

Section 1462 reads, in pertinent part, as follows:

§ ll~62.

"Whoever • • • knowingly uses any , , . common carrier,

for carriage in interstate commerce • • • any obscene • • .

motion-picture film • • • shall be fined no:t more than

$5,000 or imprisoned not more than 5 years • • . •

The indictment charged appellee with carrying ..83 -,reels . of film

from San Francisco to Milwaukee . The films were not described,

-~

it only being noted that several of the film containers contained

lot"

the same number, indicating that they might be duplicates.

Neither

II

was it charged that appellee intended to use the films for

commer~

cial purposes,

The DC dismissed the indictment on the strength of Stanley v.

-

Georgia, supra finding that the statute was overbroad and infringed

on protected activity.

The Government has taken a direct appeal

under 18 .: u .s.c. ~ 3731, which allows direct appeal from the dismissal of an indictment premised on the invalidity of the underlying statute.

CONTENTIONS OF THE PARTIES

(1)

QUESTION # l

The statute, on its face, prohibits any transportation of

.....--.

obscene material in interstate commerce, irr;spective of the purpose

"'"

for which it is being transported.

The statute draws no distinct-

ion between transporting for private use as opposed to transporting for commercial distribution.

On this record it is impossible to

do more than speculate about what this appellee's purpose might

have been.

Therefore, the first question presented is whether the

statute is unconstitutionally overbroad because it allows prosecution

for transporting obscene films for purely private use.

Both sides

agree that Roth , Stanley, Reidel, and 37 Photographs are the

pertinent First Amendment precedents.

'. '

Those cases are discussed

more ful l y in the Carrell Memo (pp . 3~11; 14-16) . and I will

m

only su~rize them here. Roth held that obscenity was not entitled

to protection under the First Amendment since by definition material

which is obscene is utterly without redeeming social value (see

also Memoirs v. Massachusetts , 383 U.S. 413).

That case (Roth)

involved commercial distribution of obscene materials and Justice

Marshall pointed out in his si bsequent opinion in Stanley v.

Georgia , supra , that none of the Court ' s obscenity precedents

"--

~

.

...

'

-

had explored the questions of private use of obscene material in

the home.

In ~!!._Y the Court held that a man could not be prosecuted

I

for ?osse;;ron ~ obscene material (here films) in his home.

The

Court found that the State was without power to prohibit the

pri~

vate use of such materials.

The subsequent cases , Reidel and

37 Photographs , as well as the two cas es to be argued this week

(the instant case and 12 200 ft reels) are concerned with the

scope of that decision.

In Reidel the Court held that the right

to peruse obscene materials in the privacy of one's home does not

carry with it the concomitant right on the part of a commercial

disseminate

distributor toI\ rMM£1. obscene materials through the mails. Justice

-

White (with whom the CJ , Brennan , Stewart and Blackmu n joined) held

-·

-.,,

that this case was covered by Roth.

-'

o~9e~.ty ~

Amendment.

its

dis~ribution

For them,

~ clearly

placed"l

outside the reach of the First

~

Stanley did not overrule

Roth in the opinion of a

majority of the Court.

In 37 Photographs the defendant was

challenging the Government ' s right to seize at the border obscene

material.

~

Luros , the owner of the photos , claimed that if he had

a right to possess obscene material in his home he had the right to

import it for that private purpose..

After noting that Luros was

importing for use in a commercial publication to be distributed to

.

,.

the public, the Court held (plurality.-.-White, CJ, Brennan, Blackmun) that the federal Government could act to keep obscene material

out of the stream of commerce even if it were designed entirely

for private use.

The Government now contends in this case that Reidel and

37 Photographs have placed a gloss on Stanley which should be

dispositive of this case.

They argue that if one does not have

a constitutional right to import for private use then he does

not have the right to transport in interstate commerce for private

use.

The appellee views 37 Photographs and Reidel as cases dealing

merely with commercial distribution and with the distributor's

right rather than the right of the user of the material.

a.pp~/1-e e.

There-

~.-Jue.s ,

fore 'A they do not diminish Stanley 8 s holding of the right of

private use.

Appellee sets up a string of hypotheticals in an

effort to show the logic of his point.

First he assumes that one

is free to read an obscene book on a bus or other instrumentality

of interstate commerce.

This he views as consistent with the

individual's right to receive material in private.

Second, if

he has a right to read it, he has a right to carry it in his pocket.

Tlt;..c/,

_.rf ne has a right to carry it in his pocket, why may he not carry

g

it in his bagg'f for reading at a later time?

Discussion of first issue

he concludes that it deals only with the imporation for commercial distribution.

The Court, although unnecessary to its judg-

ment, clearly held that importation for purely private use would

still be prohibitable.

howe~er,

That case is different than this,

in that it involved the question of keeping obscenity

out of the country whereas in this case the question is interstate

trasnportation of material already within the

c~0untry.

That is

probably, realistically speaking, a difference without a distinction.

,

And, of course, ta represents the view of only

~.

I am impressed by the suggestion in the Carrell memo.

The

approach he suggests, focusing on the few legitimate interests of

....

. . . .,.

_..,_""" --the state and federal government in limiting obscenity law to

.....,.........,'7t"'~-

____

•.

cases ............

in which it was made available to children or forced on an

--

unwanting

pub~ic

the merit of relieving this Court of much

1 has

.,._ ... _..,,.

of the volume of its cases in this area without sacrmficing

..........

the real interests worthy of protection.

I would add to that

approach that in cases in which it would still be necessary to

define obscenity I would retain the present Roth-Memoir standard

-

..f!""l&.l

but allow the state and federalAcourts greater leeway in finding

whether particular material falls within the standard.

This is

essentially Justice Harlan's view and I agree with it.

If the Court is not to re-evaluate the entire area then I

is controlling although I do find that

I

decision inconsistent with the premise of Stanley. If the Cour·t

is to re-evaluate,I urge close consideration of adopting a

composite of the Marshall and Harlan view (look to the state's

Y~w

legitimate interests in limiting obscenity; in defning it

allow broader local discretion).

(2)

Question# 2

This question is relevant only if the Court agrees with the

DC that the statute is overbroad in its proscription of transportation for private use.

The issue is whether the DC acted properly

in holding the law ·unconstitutional on its face or whether it

should have heard the case and given the statute a narrow construction to preserve its constitutionality, i.e., read the statute

as proscribing only commercial transportation.

On this leg of the case, the Government supposes that appellee

,

.

..

probably was transporting for commercial rather than private use.

This the Government infers because there were very many films

and some of the cartons were marked with the same number indicating

the possibility of duplication.

The indictment did not charge

I

commercial distribution.

If we knew this appellees

purpose in

transporting the films we would be faced with the question whether

the appellee had standing to raise the unconstitutionality of the

law.

Some Justices, notably the CJ, believe that one whose conduct

is clearly prohibitable by a statute may not complain that it is

overbroad and, therefore, might restrict the activity of someone

whose conduct is not constitutionally prohibitable.

The pre-

vailing view, however, is that where a statute is vague and

overbroad in the first amendment area, anyone who is touched by

the statute may challenge it.

-

Irrespective of this problem, I

think we may not resolve the standing question on this record.

V(

On the question whether it would have been more appropriate

to give the law a narrowing construction rather than strike it

down, appellee points out that a law may be narrowly interpreted

only when the law is susceptible of two or more interpretations

and one of them is constitutional and one not.

When the law is

clear and unequivocal the Court may not rewrite--that is a task

for the legislature not the Court.

this case.

The statute makes it a crime to use any facility of

interstate commerce (common carrier)

film.

I think that doctrine covers

t~

transport any obscene

It is clear that the law was written to exclude all trans-

portation not merely traasportation for commercial distribution.

I tf{,S

Appellee directs the Court's attention to 18 U.S.C. § which makes

"

it unlawful to transport in interstate commerce any obscene material

for the "purpose of sale or distribution."

The absence of similar

language in section 1462 is indicative that that section was

designed to have broader application than 1465 •

..

The question is not without difficulty.

The Government points

out that in a footnote in 37 Photographs Justice White notes

that if the DC had felt that the federal law was merely overbroad

in its application the court should have construed it narrowly

and applied it to the defendant in that case (see footnote 3 of

majority opinion).

For the reason stated--that the Court may not

reconstruct legislation where there is no ambiguity--I think

'

White's d~ctum is not controlling.

If the Court holds that

private transportation is protected, then I think it was proper

for the lower court to strike down the law.

Congress will then

have the task of writing a new law limited in its scope

to commercial distribution.

CONCLUSION

If no re-evaluation of existing precedents is to be undertaken,

the 4-man opinion in 37 Photographs would appear to cover this

case.

If the entire area is to be re-examined, a composite

Harshall-Harlan approach suggests itself to me as a way to

solve this Court's "involvement" problem and at the same time

protect the

11

private use 11 interests of the individual.

Even if

the law is overbroad I do not find it susceptible of a narrowing

and saving construction.

LAH

7

~N~: ~

'fcc

~- ~· v M~. ) '1-tr; F. 41.1$-G

~~~ s,~ ~~4-~~~ ~

iJ

~(ltv~~)

f.....~"'b.J

U-t~~~s~~~·

/D~

,

~1~~~14/~·.

J a_ c_;_, ~-v..J ~~ /.}-(.~ ~~

-~:So-t?~~~-~~~

1-

~~~. ~~~~~

~~~s~~5~ ~~~~~ -k ~:> ,~,

71-~~~~~-~

~~4 uy ~.

-

->

}~ ~ f6J._ ~~~\'_ ~ ~

:.-v

~~kL?~~

~·

5Pc::.... I Cf{s; L ~ ~ -.f--0 ~

~ ~~~~~

~ ~ C;f. ~v~- ~~ f/k;_,

/1.-~ ~ ~~tv rkJ ~'-Z Lt.

( ({_~ t!ls; & ~~. ~ ;Lo ~vv__~) .

Sf:ts__~"Q ~~ ~kR ~I~

a-c..~~".. ~·c:;:_ ~~~ ~

~ ~

llf(o-z_

¥-co~~ 1-o

~ ~~~ ~ _t_,L. I~"

-~~~~ . '

.

' '

'

.

~~5~~~~~0

t:):_

Cv~ ~ t>~~ ~. ;;;._~~ 0·~4/1-'-

4---~ -~ -1-o ~ ~ ~/U-v..-~1 ~

Jf-

i

Vt.--~~~5~~-~~

I-1D ~ ~-~ ·~. /i~

•

1A .~

~:::r

~ L / _ _.-,.A.

r~,\..~

~

~~v

~vy~~

.. 11 ..

l

lfp/ss

1/20/72

No. 79-69

U.S . v. Orito

Argued 1/19/72

This case , similar in many respects on principle to 12 200 Ft. Reels

involves the validity of 18 U.S.C.A. Section 1462, which prohibits the interstate transportation by common carrier of obscene material.

Section 1462 broadly prohibits such transportation, drawing no

distinction between purely private use and commercial or other proposed use.

The defendant, Orito, was indicted for transportimg obscene

material by carrying 83 reels of film from San Francisco to Milwaukee by

airplane.

He claimed this was for his own private use, and the government

could not disprove this.

See my notes on 12-200Ft. Reels.

For the reason there stated,

I incline tentatively - subject to conference discussion - to the view

that Stanley established the principle of validity of private use, and it

is difficult to say that this principle is applicable only to possession

in one's home.

Unless the Conference discussion, plus my further study,

sheds new light on this, I am inclined to affirm the judgment of the District

Court - which found that the statute was overly broad and infringed the

First Amendment right to private use.

Con£. 1/21/72

Court ................... .

Voted on .................. , 19 .. .

Argued ...1/.~~0? ......... , 19 .. .

Assigned .................. , 19 . . .

Submitted ................ , 19 . . .

Announced ...... .......... , 19 .. .

No. 70-69

UNITED STATES

vs.

GEORGE JOSEPH ORITO

/zf/71=======================

=============================~t====t

·

HOLD

FOR

CERT.

Powell, J .... .. ........ ...... .

Blackmun, J ................. .

Marshall, J .................. .

White, J ..................... .

Stewart, J ................... .

Brennan, J ................... .

Douglas, J .................... .

Burger, Ch. J ................ .

NOT

MERITS

MOTION

AB-

~---r--+---.----.----.---+--,.....--1---r----lSENT VOTG

Rehnquist, J .......... ... .... .

JURISDICTIONAL

STATEMENT

D

N

POST

DIS

AFF

REV

AFF

G

D

lNG

DouGLAs,

BRENNAN,

STEWART,

J. ~

J.

BLACKMUN,

J.

REHNQUIST,

J.

J. a_u_,__,.,:.A~

--LL_,:.;:..:.::;

~~~~-. ... C'

"2-1-6..~ -;

WHITE,

J.

~

.~.,.~_....~

~u:p-rmtt Q}~ud ~f t4t 'Jilttitt~ j)taftg

'J/D'a:Gl(htgron.lO. Q}. 2!l.;t'!-.;t

June 14, 1972

CHAMBERS OF"

THE CHIEF JUSTICE

l

l'

No. 70-69 -- U.S. v. Orito

Circ

MEMORANDUM TO THE CONFERENCE:

la~..

JUN 14. 1972

a.: _______

_

Recirculated: ___._________

I have regarded our pending obscenity cases as something of a

age" problem.

11

pack-

Here are my views on the above case on the assumption there

is a court for all since they are related.

Appellee Orito was arraigned in the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Wisconsin on a one count indictment charging that he

had violated 18 U.S. C. 1462 in that he did ''knowingly transport and carry in

inter state commerce from San Francisco • • . to Milwaukee . • • by means

of a common carrier, that is, Trans World Airlines and North Central Airlines, copies of [specified] lewd, lascivious, and filthy materials.

11

The

materials specified included some 80 reels of film, with as many as eight

to ten copies of some of the films.

Appellee moved to dismiss the indictment

on the ground that the statute violated his First and Ninth Amendment rights.

The District Court granted his motion to dismiss on the ground that the

statute was unconstitutionally overbroad under the First and Ninth Amendments, relying chiefly on this Court's prior decisions in Redrup v. New York,

394 U.S. 767 (1967) and Stanley v. Georgia, 394 U.S. 557 (1969).

-2It is not entirely clear whether the District Court viewed the

statute as overbroad because it covered transportation intended solely for

the private use of the transporter, or because , regardless of the intended

use of the materials, the statute extended to "non-public" transportation

which in itself involved no risk of exposure to the children or unwilling

adults.

18

usc

The United States brought this direct appeal under former

3731.

Under United States v . Thirty-Seven (37) Photographs,

402 U.S.

363 (1971) and United States v . Reidel, 402 U . S . 351 (1971) it is clear that

the statute in question may be validly applied to prohibit interstate transportation intended for subsequent commercial distribution or public exhibition.

On the other hand, in United States v . 12 200-Ft. Reels of Super 8 mm..

Film, et al., ante a t - - - - - - - ·' we have held that 19 USC 1305(a) may

not be applied to prohibit importation of such materials intended solely for

the private personal use of the importer .

There is no logical basis to

distinguish the instant case from that holding .

Indeed, the privacy interests

of the importer at the border would appear less substantial than the interests

of a citizen travelling in interstate commerce within the United States, given

the pervasive sweep of a sovereign 1 s control of its borders.

In either case ,

the non-public transportation of obscene materials intended solely for the

private use of the transporter falls within Stanley v. Georgia.

Thus, we must conclude that the statute in question cannot validly

be applied to reach interstate transportation of obscene materials intended

solely for the private use of the transporter.

It does not follow from this

-3conclusion, however, that the District Court was correct in striking down

the statute on its face.

Whatever "chilling" effect the statute might have is

easily eliminated by limiting its applications to cases in which the transportation is for the purpose of commercial exploitation or public exhibition,

as opposed to transportation for the purely private use of the person transporting it.

Here, as in U.S. v 12 200-Ft. Reels, supra, the claim of

private purpose and use will inevitably lose some of its force if the carrier

transports multiple copies or if he exhibits to others and especially if

there is any access permitted to minors.

Therefore, the statute may be

sustained by drawing a clear line between its constitutional and unconstitutional

applications; there is no basis for invalidating the statute on its face.

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479, 491 (1965);

See

United States v.

Thirty-Seven (37) Photographs, 402 U.S. 363, 375 n. 3; id. at 377 (Harlan,

J., concurring); id. at 379 (Stewart, J., concurring).

Accordingly, the case must be remanded for fu rther proceedings to

the end that the District Court may inquire into the government 1 s position as

to appellee 1 s

intended use of the materials.

appropriate to permit

In our view, it would also be

the United States to obtain an amended indictment

specifying the purpose with which it is charged that appellee was transporting

the materials.

Regards,

.

'

.ju;vumt <.!fcurt cf tqt 'Jitnittb' ,jtaftg

~aglftttghm. ~. <!f. 2ll~J!.~

June 14, 1972

CHAMBERS OF'

THE CHIEF JUSTICE

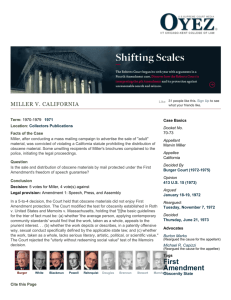

No. 70-73 -- Miller v. California

Dear Bill:

I have your very interesting memo on the broad problem of the

above case.

this job.

In the short time you have had I marvel at how you have done

We need more exchanges of this kind to develop our thinking.

Given the lateness of the season, I will undertake to comment

with less than the time I would like on a matter of this importance.

1.

I accept your proposition, if I read you correctly, that the Court

has not been able to come up with a definition that will separate protected

from non-protected

2.

11

sex material.

11

I think I agree that people in the commercial world are uncertain

of the standards.

We are, and they merely reflect our uncertainty.

I con-

fess I do not see it as a threat to genuine First Amendment values to have

commercial porno-peddlers feels some unease.

For me the First Amend-

ment was made to protect commerce in ideas, but even at that I would go

a long way concerning ideas on the subject that has had a high place in the

human animal's consciousness for several thousand (?) years.

a little

11

chill 11 will do some of the

good for the country.

11

In short,

pornos 11 no great harm and it might be

~-

Even accepting that the "Redrup technique" compounds uncertainty,

I prefer it to a new, uncharted swamp.

3.

I strongly agree with you that there are some obscene materials not

protected by the Constitution.

4.

I agree we must at some point make it possible for governments

to stop pandering and touting by mail or otherwise with brochures, etc.,

that offend.

5.

My views in Rowan coincide with your memo.

I agree (if it is your view) that all public display that goes beyond

mere nudity and depicts or sugges1s conduct can be barred.

I think if it can

be barred on 14th and Constitution Avenue, it can be barred in a saloon and

probably theatre • .

6.

I consider the state free to make a serious felony out of any conduct

that permits access of minors to non-protected material.

7.

In general I agree that traffic via words in print is in a different

category from pictures, movies, or live shows.

I would cover this by the

"access" and "anti-solicitation" route.

8.

I read your memo as drawing substantially on the recommendations

of the Commission on Obscenity and Pornography. For me, the Commission 1 s

Report is interesting but I do not think I am ready to make it a basis for

constitutional adjudication.

I question the ••ripeness 11 of the ideas of the

Report.

9.

I am by no means content with my own approach in the Miller memo

I circulated, but the Court has made enough false steps.

We now need to

-3retrace so that I feel we need to be very cautious about embarking on a

new broad scale "solution.

11

I fear that no solution will ever really be

final -- First Amendment problems do not readily "finalize."

Since I circulated my Miller memo on May 19, I put my hand to

something of the course you have laid out , but I concluded it was, for me at

least, not ready for circulation.

I think I would prefer to continue with one step at a time, clarifying

the "national standard" concept in Miller

to "marinate.

and let the other problems continue

11

I would therefore stand on Miller as proposed, but treat Thurgood's

Stanley holding as I have in my memo on the border-importation case, and

would follow the border case in Orito

for interstate commerce .

Within this framework, I welcome suggestions that would lead any

others to join Miller in what I consider to be a step-by-step treatment of one

problem at a time .

Mr. Justice Brennan

Copies to Conference

6/15/72--LAH

Rea Obseenity Cases

Judge a

It occurred to me that during the discussion at conference this morning questions are likely to arise regarding

the three obscenity cases under submission.

I thought, there-

fore, that I should refresh your memory and bring you up to

date on the latest developments.

First, in Miller v. California

the CJ has circulated a memorandum in which he basically

concludes that local standards govern questions of the content

of allegedly obscene material and that this is essentially

a question for the jury based on a determination whether it

transcends local levels of decency and good taste.

As my

short note to you in that case indicates, whatever approach

the Court is to take, I cannot justify that one.

It is flatly

contradictory to the entire course of constitutional

adjudication under the First Amendment.

Moreover it presents the

gravest questions of vagueness--convicting a man for the sale

of something that he had no way of knowing would be found

obscene.

Justice Brennan has circulated a long memorandum,

a copy of which you have, in which he propaes another alternative basically premised on the interest analysis approach.

No one, to my knowledge has joined either side yet.

Second, in Orito (the case involving the federal statute

against interstate transportation) the CJ has circulated a

memo which is attached.

Justice Douglas has circulated a

dissent or contrary memorandum.

Orito, like Millerp turns

to a significant extent on the question of private v commercial

use.

It is in my view inextricably intertwined with Miller.

Finally, the CJ has just circulated a memo responding the

Brennan memorandum.

It points out, I think, the complexity

of the cases.

I suggest that if the question is raised you consider the

possibility of reargument of all three of the pending obscenity

cases.

They are interrelated and terribly complex.

The

primary interest is in finding some cohesive apprach which

will serve the First Amendment and at the same time end

this Court's involvement and provide an underst andable framework for the lower courts.

There simply is not adequate

time at present for so ambitious and important an undertaking.

UH

October 24, 1972

Memorandum to the file

From: Lewis F. Powell, Jr.

Obscenit~ Cases

(Notes on Court onference)

Bill Brennan

Our problem differs from England as we have the First

Amendment.

~~

~~-A4/

au ~~cc.r.aJ

Roth established that obscenity is not protected by the

First Amendment. It also established that all erotic expression

has protection unless it is obscene. Finally, whether expression

is obscene is a constitutional question which we cannot delegate

to juries. (Bill cites John Harlan and also Bill says Redruet

so held unanimously. )

have

Since Roth, there JmB never been five votes in accord as

to what the definition means.

This has resulted in two problems: (i) vagueness for

parties, and (ii) institutional uncertainty on part of law enforcement and legislature.

Stanley departs from Roth. Its principle is contrary to

Reidel and 37 Photographs. Bill, who joined these two cases,

now would overrule them.

I

I

-2Bill now thinks state may control erotic material rather

than suppress it. This control may be rational state action if it

applies only to minors and non-assenting adults.

if".u..u-.:c..,~

~

Bill would redefine in specific terms -e.g., description of proscribed material (e.g., actual or simulated intercourse).

He referred to Oregon statute.

~M-­

~e.-'

~~

Bill would allow states or Congress to proscribe obscene

live shows even for adults. This is conduct - a view shared by

~~y. Douglas. But Bill distinguishes motion pictures from live shows -

arguing that a movie is "expression" not conduct.

As to minors, Bill has modified views expressed in his

memo. He now likes Harlan's dissent in Jacabellais which suggests

"standards" Bill would now accept as to minors. This would enable this Court to review only the standards and not the particular

expression.

(But how does this position square with Bill's view that

we cannot delegate to anyone the responsibility of determining what is obscene l)

Would not require expert testimony.

-3-

Potter Stewart

Would draw no distinction between live shows and

movies.

Cases before us all involve lburteenth Amendment state

action. It is settled that First Amendment has been incorporated.

Two of the cases next week involve Federal statutes. Harlan

and Jackson thought that in obscenity cases the First Amendment

was not adopted in its entirety. Potter thinks we would have to

overrule long line of cases to accept Harlan's view.

States may regulate and protect minors.

States also may protect unwilling public from what may

be an'assault" on their sensibilities.

Byron White

Thinks we have over-emphasized the obscenity issue.

If in legislature, he might eliminate most obscenity

laws. But as judges, we must decide whether all state and Federal

obscenity statutes are invalid.

Specific definition -of acts (intercourse) -of hard core

would help.

-4-

There should be national standards for definitional

purposes -but allow juries to apply community standards within

the definitional standards.

In general would adhere to Roth.

Would not overrule Roth but would redefine obscenity

in terms of specifics.

Would make no distinction between adults and minors

or consenting and non-consenting. If definition is sufficiently

explicit -even narrower than Oregon statute -he would allow

states to regulate as to everyone.

****

have

There laal never been five votes for the Jacabellais

and memoirs for "redeeming social value."

Thurgood Marshall

With Brennan.

Likes Oregon statute.

.. :.. . .•

~

",;.'

-5Harry Blackman

Closer to White and Chief than to Brennan.

Emphasized key role of jury as reflecting community

judgments.

Would not overrule Roth. Would re-examine definition.

Does not agree that printed text cannot be regulated.

What about Suite 69 ?

But is intrigued by Brennan's "privacy" rationale.

Bill Rehnquist

Not sure that Harlan's view is wrong. Certainly up

to time of the Fourteenth Amendment, states were free to regulate

obscenity.

Would reaffirm Roth with greater specificity.

We should vote to deny cert more regularly than we have

in past.

MY NOTES FOR CONFERENCE ON OCTOBER 24, 1972

Complement Bill and Chief

At time First Amendment was adopted, no one then

thought that it protected obscene expression from legislative

regulation or control.

I agree with Roth formulation that obscenity is not

protected expression.

I think I would have voted with majority in Stanley accepting its disclainer that it was undercutting Roth.

The problem that has confounded everyone is how to

define obscenity -vagueness, etc. I would not overrule Roth

but would redefine in terms of specific standards.

Definitions can be made specific - except as to books.

Some sort of administrative procedure would help on

vagueness issue.

Am closer to Chief than to Bill- but am unsure on several

points and will await next drafts of opinions.

L.F.P.,Jr.

LFP, Jr. :pls

', '

70-69 U.S. v. ORITO

No.

~

~~ -1--o

'

~

Argued 11/6/72

/z_- 2-u

~~~ i<:>

fd. ~ ~~

,

~~

·

c.?

I

g

Q

S C.., f<.{{o 2..

L--L..

~ ~ ~~

I

~ ~1-t.J_

-f:t-4 ~ ,.~

Ly TuJ/1- ~~

~ ~ ~lW.f4;:)

~

~ ~ .

~HJ._ (~,,~

~

·~ .

~~

~~~~

~(/l>)-L1 ~ ~

~~· &-/ ~~ ~ · ~

~~oY~~}

~/&~ ·~~ -

-~~

/

~~c~~

v-w._~ ~ ~37 J?~~~

Vz-

C-t/).<_,

~-~

~. ~of d2a~ ~~­

LQ .

s ..

~~ ..f-D ~ ~~

~·

LV+-t.-

~~J ~~

~(~)

~D--e~~~

~~~~.

&..>--_

~

~.

1-W._

U... S.

-

~

v

_,)

1--t:J

~~

Z

•

l-u

'~

~

·- - - kits.eeJ

~

•

s:>2- F.~ '883

u. ~. ~.) ~~

~~~~~~~a_~

1---fu_ ~

~

t...c...-

~

~

7

~.

~~37~

u..J.-L

u..

<;:, V, 7.~.

a 1 jzt: ~

'f6 -z-

~ ~.

u..___

! .1r1

~ ~ ~

~~(~6)~~

~ ~~c¢1

~·

u. s. (/

c

'

2~ 332- /-::. ~· 8'"ff2 L-t--

~~

LL

/_(J

~ ~(~~);'1---

~~~ai/f

~. ~~

~ ~~~~fd-1JL&/~

s· ~ '---'-'

ov-e.-v - ~ ( 1 'if u. s c

/L_~-J....

1769/t 0 ~ ~

l'f!(.:j

~~ ~ ~ It~ UA._-~ 1-o ~ '\

- - -- - - - - - - r

~~ -~

~{yOCf ~~

~~t7(~

~

_ 5~~~~~~~

~ .

w~~~~~~~

'

1--<J ~~ .~ ~ ~~

~¢:o.

,/

'~~ -

~~ '4tJ-~ ~41\~

:_y ~ ~

~ ~LJ- ~ N--u~t..::f

~~~~~~~~~

tt~e~~

~.

'

~ ~ ~ 12-<!) ~-~

~ t..::1 ~/1..-VQ ~ ~

/h_;_-4

~

~

~~

~ ·

I

~

-

~~~~~~~

~

~9

.<:7-J

~~~-~--~~~

/~ ~~

·-k ~~ · ~ ~

~ ~~

____

w-Dz-z-

KJ

~

~~/-tA-t~

..:.____ - - - - - "

~

4--0

o-v-"--v-~~

~~-v4 ,.

6-.H-

~(-{-

Conf.

11/1v/72

Court ................... .

Voted on ............ . .... . , 19 .. .

Argued .. ....... ....... . . . , 19 .. .

Assigned . . ....... .... . .... , 19 . . .

Submitted ............... . , 19 . . .

Announced . . ... . ...... .... , 19 . . .

No. 70-69

u.s.

vs.

ORITO

.L

HOLD

FOR

CERT.

G

Rehnquist, J ................. .

Powell, J .................... .

Blackmun, J ................ . .

Marshall, J .................. .

White, J .... . . . .............. .

Stewart, J ................... .

Brennan, J ... . ............... .

Douglas, J .................... .

Burger, Ch. J ................ .

D

JURISDICTIONAL

STATEMENT

N

POST

DIS

AFF

MERITS

REV

AFF

MOTION

G

D

AB-

NOT

VOTSENT lNG

I

{{;

~

-r6

f-

c

~

d~

1

'=t

1,

q

0

~

J-.4

0

:>

(/)

::::)

~

co

I

0

t-

1-

.-;

'-'

0

~

::q

~

~ ~ t~l~~,_ ~~

,... 't~

~ ~---~

~~

~~"

~J~~

"' ~

~

-.!:_

~

'~

-!

~

........._

~

,,~

~

~

I