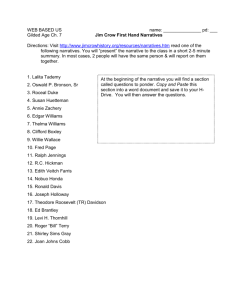

Slave of the Slave - Faculty

advertisement