Methods of Characterization

advertisement

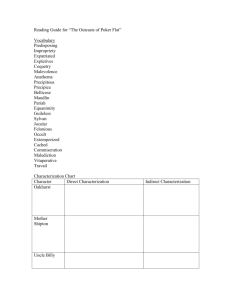

【2.2】 Methods of Characterization In presenting and establishing character, an author has two basic methods or techniques at his disposal. One method is telling, which relies on expositions and direct commentary by the author. In telling, the guiding hand of the author is very much in evidence. We learn primarily from what the author explicitly calls to our attention. The other method is indirect, dramatic method of showing, which involves the author’s stepping aside, as it were, to allow the characters to reveal themselves directly through their dialogue and their actions. With showing, much of the burden of character analysis is shifted to the reader, who is required to infer character on the basis of the evidence provided in the narrative. However, telling and showing are not mutually exclusive. Neither is one method necessarily superior. Most authors employ a combination of the two, even when the exposition, as in the case of most of Hemingway’s stories, is limited to several lines of descriptive detail establishing the scene. Direct Characterization: Telling Direct methods of revealing character---characterization by telling---include the following: Characterization through the use of names Names are often used to provide essential clues that aid in characterization. Some characters are given names that suggest their dominant or controlling traits, as, for example, Young Goodman Brown, the naïve young puritan in Hawthorne’s story, and Mr. Blanc, the reserved Easterner in Stephen Crane’s The Blue Hotel. Other characters are given names that reinforce(or sometimes are in contrast to) their physical appearance, much in the way that Ichabod Crane, the gangling schoolmaster in Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, resembles his long-legged namesake. Names can also contain literary or historical allusions that aid in characterization by means of association, as they obviously do in Woody Allan’s The Kugelmass Episode. One must also, of course, be alert to names used ironically that characterize through inversion. Such is the case with the foolish Fortunato of Poe’s The Cask of Amontillado, who surely must rank with the most unfortunate of men. Characterization through appearance In real life, appearances are often deceiving. In the world of fiction, however, details of appearance (what a character wears and how he looks) often provide essential clues to character. Take, for example, the second paragraph of My Kinsman, Major Molineux, (cf. P. 217) in which Hawthorne introduces his protagonist to the reader. The several details of the paragraph tell us a good deal about Robin’ character and basic situation. We learn that he is a “country-bred” youth nearing the end of a long journey, as his nearly empty wallet suggests. His clothes confirm that he is relatively poor. Yet Robin is clearly no runaway or rebel, for his clothes though “well-worn” are “in excellent repair”, and the references to his stockings and hat suggest that a loving and caring family has helped prepare him for his journey. The impression thus conveyed by the total paragraph and underscored by its final sentence describing Robin’s physical appearance, is of a decent young man on the threshold of adulthood who is making his first journey into the world. The only disquieting note---a clear bit of foreshadowing---is the reference to the heavy oak cudgel that Robin has brought with him. He later will brandish it at strangers in an attempt to assert his authority and in the process reveal just how inadequately prepared he is to cope with the strange urban world in which he finds himself. As in Hawthorne story, details of dress and physical appearance should be scrutinized closely for what they may reveal about character. Details of dress may offer clues to background, occupation, economic and social status, and, perhaps, as with Robin Monlineux, even a clue to the character’s degree of self-respect. Details of physical appearance can help to identify a character’s age and the general state of his physical and emotional heath and well-being: whether the character is strong or weak, happy or sad, calm or agitated. Appearance can be used in other ways as well, particularly with minor characters who are flat and static. By common agreement, certain physical attributes have become identified over a period of time with certain kinds of inner psychological states. For example, characters who are tall and thin, like Irving Crane and Poe’s Roderick Usher, are often associated with intellectual or aesthetic types who are withdrawn and introspective. Portly or fat characters, on the other hand, suggest an opposite kind of personality, one characterized by a degree of laziness, self-indulgence, and congeniality. Such convenient and economic shortcuts to characterization are perfectly permissible, of course, as long as they result in characters who are in their own way convincing. Characterization by the author In the most customary form of telling, the author interrupts the narrative and reveals directly, through a series of editorial comments, the nature and the personality of the characters, including the thoughts and feelings that enter and pass through the character’s minds. By so doing the author asserts and retains full control over the characterization. The author not only directs his attention to a given character, but tells us exactly what our attitude toward that character ought to be.