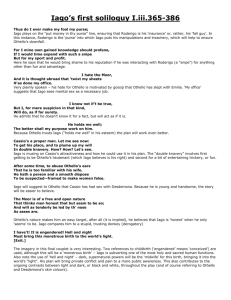

literary criticism quotes

advertisement

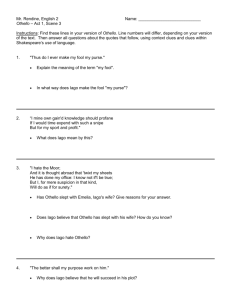

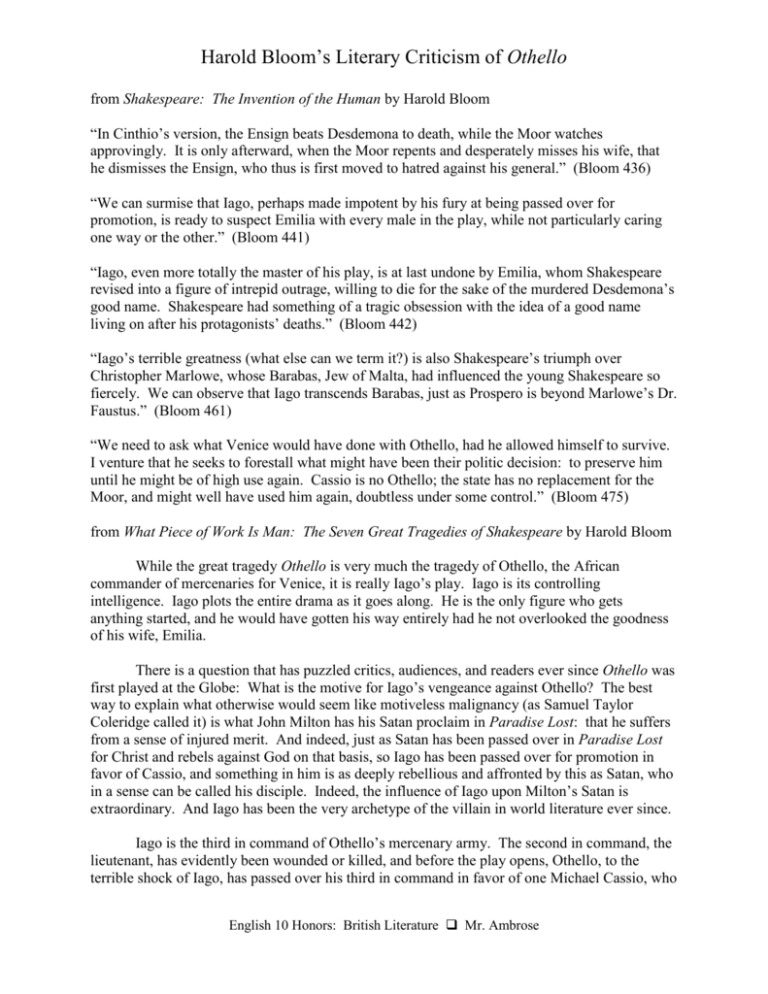

Harold Bloom’s Literary Criticism of Othello from Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human by Harold Bloom “In Cinthio’s version, the Ensign beats Desdemona to death, while the Moor watches approvingly. It is only afterward, when the Moor repents and desperately misses his wife, that he dismisses the Ensign, who thus is first moved to hatred against his general.” (Bloom 436) “We can surmise that Iago, perhaps made impotent by his fury at being passed over for promotion, is ready to suspect Emilia with every male in the play, while not particularly caring one way or the other.” (Bloom 441) “Iago, even more totally the master of his play, is at last undone by Emilia, whom Shakespeare revised into a figure of intrepid outrage, willing to die for the sake of the murdered Desdemona’s good name. Shakespeare had something of a tragic obsession with the idea of a good name living on after his protagonists’ deaths.” (Bloom 442) “Iago’s terrible greatness (what else can we term it?) is also Shakespeare’s triumph over Christopher Marlowe, whose Barabas, Jew of Malta, had influenced the young Shakespeare so fiercely. We can observe that Iago transcends Barabas, just as Prospero is beyond Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus.” (Bloom 461) “We need to ask what Venice would have done with Othello, had he allowed himself to survive. I venture that he seeks to forestall what might have been their politic decision: to preserve him until he might be of high use again. Cassio is no Othello; the state has no replacement for the Moor, and might well have used him again, doubtless under some control.” (Bloom 475) from What Piece of Work Is Man: The Seven Great Tragedies of Shakespeare by Harold Bloom While the great tragedy Othello is very much the tragedy of Othello, the African commander of mercenaries for Venice, it is really Iago’s play. Iago is its controlling intelligence. Iago plots the entire drama as it goes along. He is the only figure who gets anything started, and he would have gotten his way entirely had he not overlooked the goodness of his wife, Emilia. There is a question that has puzzled critics, audiences, and readers ever since Othello was first played at the Globe: What is the motive for Iago’s vengeance against Othello? The best way to explain what otherwise would seem like motiveless malignancy (as Samuel Taylor Coleridge called it) is what John Milton has his Satan proclaim in Paradise Lost: that he suffers from a sense of injured merit. And indeed, just as Satan has been passed over in Paradise Lost for Christ and rebels against God on that basis, so Iago has been passed over for promotion in favor of Cassio, and something in him is as deeply rebellious and affronted by this as Satan, who in a sense can be called his disciple. Indeed, the influence of Iago upon Milton’s Satan is extraordinary. And Iago has been the very archetype of the villain in world literature ever since. Iago is the third in command of Othello’s mercenary army. The second in command, the lieutenant, has evidently been wounded or killed, and before the play opens, Othello, to the terrible shock of Iago, has passed over his third in command in favor of one Michael Cassio, who English 10 Honors: British Literature Mr. Ambrose Harold Bloom’s Literary Criticism of Othello is a kind of staff officer, not a battle-tested veteran like Iago. Othello is not at all aware of the extent to which he has alienated Iago. He perpetually goes on calling Iago “honest Iago,” though we realize Iago is anything but that. In act 1, scene 1, Iago is talking to Roderigo, whom he is perpetually soliciting for money. Roderigo is furious that Othello has married Desdemona, for whom Roderigo had expressed considerable interest and desire. Iago explains why he still follows the Moor: “Were I the Moor, I would not be Iago: In following him, I follow but myself; Heaven is my judge, not I for love and duty, But seeming so, for my own peculiar end: For when my outward action does demonstrate The native act and figure of my heart In complement extern, ’tis not long after But I will wear my heart upon my sleeve For doves to peck at: I am not what I am.” Ponder the extraordinary sentence: “I am not what I am.” Anyone in Shakespeare’s audience would have instantly recognized that it is set against St. Paul’s statement: “By the grace of God, I am what I am.” Iago says, “I am not what I am,” and his negation is striking. He is one of the great nihilists in literature, surpassing Hamlet in that regard. Iago has been passed over by Othello – though Shakespeare never makes it overt – because he is always at war. He does not distinguish between the camp of war and the camp of peace. Because Iago has no diplomacy and is dangerous therefore in peacetime, Othello (with great wisdom) decided that he is someone who can be relied on in the battlefield, but not someone to be placed as second in command, for if Othello were to be wounded in battle or killed, there would be a highly irresponsible and dangerous person in charge. Iago has worshipped the god of war in his captain-general Othello, just as Satan has worshipped God in Paradise Lost. When Iago is passed over, he feels completely undone. He is rendered impotent. He feels, indeed, that his whole life has come to nothing. He feels he has no dignity and no self-regard, that there’s scarcely any reason for going on, and so he turns upon his war-god, Othello, and looks for a way to return that god to a kind of original chaos. Iago’s soliloquies are very unlike those of Hamlet. They’re not the soliloquies of a master of consciousness. There is a tremendous internalization of the self, a tremendous new kind of inwardness, that does make Hamlet a new kind of human being. Iago is a Machiavellian figure. He is a villain. But he is a highly original villain. It is one of his curious attributes that he rally has no emotions, no affective life of any kind, so that he first invents or makes up emotions, such as jealousy, and then he pretends to feel them. English 10 Honors: British Literature Mr. Ambrose