Case: Circuit City Stores, Inc

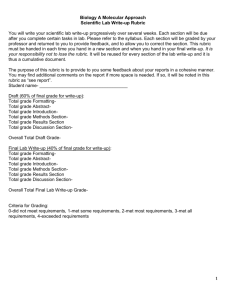

advertisement

The University of Illinois Executive MBA Revised August 5, 2000 Managerial Perspective on Financial Accounting Accountancy 401X; Fall 2000 Michael J. Sandretto, 302 Commerce West (217) 244-6410 (office); (217) 352-4832 (home, before 10:30 p.m.) sandrett@uiuc.edu or mjsandretto@ibm.net Texts: Stickney, Clyde P. and Roman L. Weil, Financial Accounting: an Introduction to Concepts, Methods, and Uses, Ninth Edition, The Dryden Press, Harcourt College Publishers (Fort Worth, Texas), 2000. Stickney, Clyde P. and Paul R. Brown, Financial Reporting and Statement Analysis: A Strategic Perspective, fourth edition, The Dryden Pres, Harcourt College Publishers (Fort Worth, Texas), 1999. Afterman, Allan B., SEC Regulation of Public Companies, Prentice Hall (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey), 1995. Course Objectives: Accounting is often called the language of business. It is management’s primary tool for learning about an organization’s economic condition and performance and for communicating that information to others. Managerial Perspective on Financial Accounting is a course for managers about accounting. While it is designed for general mangers, it is useful to investors, regulators, and those in technical positions. The course should help you: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Understand and evaluate an organization’s financial condition and operating performance. Plan future operations and estimate the results of current decisions. Communicate plans and goals with others. Compare actual results with plans to understand the effect of past decisions and learn from them. Help control an organization Communicate the results of operations to external constituents such as shareholders, lenders, suppliers, customers, and regulatory agencies Objectives of accounting Accounting has been developed over at least the past 500 years. Accounting includes several systems, including its most basic system, double entry bookkeeping. There are other major systems such as cost accounting systems that help determine and control costs. Cost systems are separate from financial accounting systems such as double entry bookkeeping, but the better cost systems are closely integrated with financial accounting and production systems. Accounting also consists of many rules about how to record transactions or events. The primary rulemaking bodies in the U.S. are the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), a private rule-making body, and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), a part of the Federal Government. The purpose of financial reporting has changed over the years. Until about 1960, its primary objective was to correctly value assets while retaining the historical cost principle. That is, accountants record transactions at their historical cost. Traditionally, accountants did not change recorded amounts for increases or decreases in market values. With value as an objective, accountants tended to focus on how items such as inventory valuation and depreciation methods would affect the balance sheet. 1 In about 1960 accountants began shifting focus to economic performance. With that objective, accountants focused on the income statement and on matching revenues with costs that generated those revenues. In the mid-1970s accountants again shifted focus to providing information useful for predicting future cash flows, which analysts use to estimate a firm’s value. Currently, accounting rules are a mixed bag. Some rules focus on valuation, some on matching costs and revenues, and some on helping with cash flow predictions. In some cases accountants retain the historical cost principal; in other instances they record current asset values. Changes in Business and Accounting Within the past ten or fifteen years publicly available financial statements began to include considerably more information than in the past. At the same time, those financial statements have become less useful for valuing companies. Part of the problem lies with the nature of business. In the past, most of a company’s value consisted of physical assets, supported by simple financial structures. Now, intangibles such as patents, trademarks, copyrights, and software are often a firm’s main assets. In many cases, intangibles are shown on a firm’s balance sheet at a minimal value or a value of zero. At the same time, financial structures became more complex. Companies now issue large quantities of employee stock options and many issue debt convertible into stock, or preferred stock that must be converted into debt. These financial structures make it more difficult to analyze a business than in the past. A second problem is that companies are more complex. They are larger, operate in more countries, and use complex hedging to limit their risk. As a result, it is far more difficult to estimate the value of a firm’s assets, to determine a firm’s performance, and to estimate a firm’s future cash flows. A third problem is that companies change far more rapidly, so reported net income may be a poor predictor of future income. Examples include major and frequent restructurings at companies such as AT&T and the explosive growth at Internet companies such as e-Bay. Finally, analysts, investment managers, and other outsiders place far more pressure on management. In the past, a board of directors often consisted of a friends and relatives of a company’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO). Now, because of pressure from the SEC and major shareholders such as CALPERS (California Public Employees’ Retirement System), most boards are independent and they regularly remove CEOs. As a result, companies probably distort their accounting earnings more than in the past. This is a major concern at the SEC. Course Objectives In the past, financial accounting consisted of a few rules and several guiding principles, such as historical cost, materiality, and matching revenues with expenses. Now, the FASB has hundreds of mandatory rules, as does the SEC. There are far too many complex accounting rules to cover in a single accounting class, or even in the course work required for an accounting degree. We will cover several accounting topics in some detail, but this course is not designed to cover most of the finer points of accounting. Rather, it is designed to provide a broad exposure to how managers can use accounting to manage their business, how they can report the results of operations, and how they can use external auditors to help communicate with others. The course consists of four parts: 1. Accounting camp. An introduction to double entry bookkeeping, cost accounting, discounted cash flows, and financial reporting. 2. The five-day week and the two classes before mid-term. Understand financial statements, revenue recognition, depreciation, inventory valuation, discounted cash flows, costs, expenses, and liabilities. 2 3. After mid-term and before group presentations. An introduction to special topics such as pensions, employee stock options, restructurings, and company valuations. Each study group will prepare one group write-up/case presentation. That will include a 5-15 page case write-up, a 2-5 page Executive Summary for your classmates, and a 30-35 minute PowerPoint presentation, followed by 5-10 minutes of questions.. 4. A group project that may consist of either (1) an evaluation of two, three, or four companies in an industry; (2) a detailed study of one company, which may be a company where a group member is employed; (3) a comparison of a traditional firm, such as General Electric or GM, with a highgrowth high-tech firm such as Cisco, or with an Internet startup such as e-Bay; or (4) some other project approved by the instructor. If you have a project for a company where a group member is employed, the project need not be strictly related to accounting; all that is necessary is that there is a reasonable accounting component to the study. Each write-up should consider detailed accounting issues such as pensions, where relevant. The write-up should also evaluate the financial condition and performance of each company, and may include a valuation based on projected financial statements for one or more companies. Each group will have 30 minutes for their presentation. That will include five minutes for setup, 20 minutes for a presentation, and five minutes for questions. Grading: Grading is based on a mid-term and final examination, a group case write-up and presentation, the group projects, and class participation. Class participation grading begins Monday, 14 August; class participation in the accounting camp does not count toward your final grade. Grade weighting is as follows: Mid-term examination Group case write-up and presentation Group project write-up and presentation Final examination Class participation 15% 15% 30% 25% 15% I assign numerical grades for each assignment (maximum of 100 points for each assignment). At the end of the term I weight scores by the above percentages, add scores for the six assignments, and rank the scores from high to low. I then assign grades based upon the following approximate grade distribution, although I also look for reasonable breaks between letter grades, such as 1.5 points instead of .2 points. : A AB+ B 25% 30% 25% 20% The only consideration I give to an improved grade between the mid-term and the final examination is a 25% weight to the final examination and a 15% weight to the mid-term. Once the course begins on Monday, August 14, I will not change the grading system. The University considers any changes to a grading system after class begins to be capricious grading. 3 Assignments Accounting camp covers the first four chapters of Stickney and Weil. Please review the following sections of Stickney and Weil prior to class Monday, August 14: Chapter 1, pp. 3-23. Chapter 2, pp. 43-54 Chapter 3, pp. 101-111 Chapter 4, pp. 168-173 and pp. 198-201 I will pass out more detailed assignments two weeks prior to class. Monday, August 14 Case: Patton, Corp. Reading: Chapter 6, pp. 303-318, Stickney and Weil. 188-027 Assignment: Analyze the case. Tuesday, August 15 Case: Circuit City Stores, Inc. (A) Reading: Chapter 6, pp. 319-329, Stickney and Weil. Assignment: Questions at the end of the case. Wednesday, August 16 Case: LIFO or FIFO? That Is the Question Reading: Chapter 7, pp. 252-380, Stickney and Weil. Assignment: Questions and the end of the case. Thursday, August 17 Case: Depreciation at Delta Air Lines and Singapore Airlines (A) Reading: Chapter 8, pp. 410-441, Stickney and Weil Assignment: Questions at the end of the case. 191-086 192-046 198-001 Friday, August 18 Case: Kansas City Zephyrs Baseball Club, Inc (to be passed out later). Reading: Skim Chapter 5, pp. 231-260, Stickney and Weil. Assignment: Analyze the case. Friday, August 25 (short week) Case: Baylor Books Reading: Chapter 1, pp. 3-14, Stickney and Brown Assignment: Questions at the end of the case. 198-082 4 Saturday, September 2 (long week) Case: Harnischfeger 186-160 Reading: Auditors and Their Opinions, 197-113; Chapter 1, pp. 15-39, Stickney and Brown Assignment: Questions at the end of the case. Friday, September 8 (short week) Mid-term examination. This exam will consist of five or six questions based on footnotes from annual reports, income statements, balance sheets, statements of cash flow, or articles from business publications or the Internet. Topics may include, but are not limited to the following: revenue recognition, depreciation, inventory valuation, discounted cash flows, capitalization versus expensing, and costs and cost allocations. During the following ten weeks we will have group presentations. I will randomly assign your group case by Friday, August 18. Saturday, September 16 (long week) Case: 3-2, Specialty Retailing Analysis: The Gap and The Limited, pp. 187-197, Stickney and Brown Reading: Chapter 3, pp. 124-159, Stickney and Brown Assignment: Analyze the case. Friday, September 22 (short week) Case: Hicorp, Inc. 198-014 Reading: Appendix 3.1, pp. 160-163, and Chapter 11, pp. 587-599, Stickney and Brown. Assignment: Group write-up and presentation 2. Bloomington Saturday, September 30 (long week) Case: Chemdex 898-076 Reading: Chapter 5, pp. 264-275, Stickney and Weil; Chapter 10, pp. 687-721, Stickney and Brown Assignment: Read the case and text. We will discuss the case and I will then describe how to prepare cash flow projections. Friday, October 6 (short week) Case: International Paper, Case 4-1, pp. 264-269, Stickney and Brown Reading: Chapter 4, pp. 201-238, Stickney and Brown Assignment: Group write-up and presentation 3. Champaign 3 Saturday, October 14 (long week) Case: Arizona Land, Case 5-1, pp. 343-353, Stickney and Brown. Reading: Chapter 5, pp. 283-302, Stickney and Brown; Chapter 1, pp. 1-13, Afterman. Assignment: Group write-up and presentation 4. Chicago 2 5 Friday, October 20 (short week) Case: America Online: 1996-1999 100-090 Reading: Chapter 5, pp. 320-328, Stickney and Brown; Chapter 2, pp. 15-27, Afterman. Assignment: Group write-up and presentation 5. Springfield Saturday, October 28 (long week) Case: American Airlines and United Airlines: a pension for debt, pp. 446-453. Reading: Chapter 6, pp. 370-397, Stickney and Brown; Lease accounting and analysis, 100-003; Chapter 3, pp. 29-44, Afterman. Assignment: Group write-up and presentation 7. Chicago 1 Limit your analysis to lease accounting; use the two most recent years available on www.pwcglobal.com. Friday, November 3 (short week) Case: American Airlines and United Airlines: a pension for debt, pp. 446-453. Reading: Chapter 6, pp. 398-410, Stickney and Brown; Chapter 4, pp. 47-65, Afterman. Assignment: Group write-up and presentation 8. Peoria/Bloomington Limit your analysis to pensions and use the two most recent years available on www.pwcglobal.com. Saturday, November 11 (long week) Case: E-Bay and Amazon.com, to be passed out later Reading: Employee stock options; Chapter 5, pp. 67-76 and Chapter 6, pp. 79-85, Afterman. Assignment: Group write-up and presentation 9. Champaign 1 Friday, November 17 (short week) Case: Fly-by-Night, Case 9-2, pp. 659-669, Stickney and Brown. Reading: Chapter 9, pp. 619-643, Stickney and Brown Assignment: Group write-up and presentation 9. Champaign 2 Thanksgiving Break—No Class Friday, December 1 (Long week). Double Session for Group projects. Saturday, December 9 (long week) Final Examination. This exam will consist of five or six questions based on footnotes from annual reports, income statements, balance sheets, statements of cash flow, or articles from business publications or the Internet. 6 Case: Circuit City Stores, Inc. (B) 192-036 Case: Depreciation at Delta Air Lines and Singapore Airlines (B) 198-002 Reading: Auditors and Their Opinions 197-113 Case: Harnischfeger 186-160 Case: Hicorp, Inc. 198-014 Case: Chemdex 898-076 Reading: Auditors and Their Opinions 197-113 Case: In-process R&D Case: Gains and losses on securities Case: Consolidated Financial Statements Case: Hicorp, Inc. 198-014 Internet companies (1 hour) A number of Internet companies have either gone out of business recently, or announced their auditors issued a “Going Concern” opinion, which states that the firm may be unable to continue as a going concern because it may run out of cash. Using the Internet, The Wall Street Journal, or a local newspaper, collect information on at least two or three Internet companies that announce they will discontinue operations or may soon run out of funds. Be prepared to discuss your findings in class. 7