15 - Through Ellis Island and Angel Island: The Immigrant Experience

advertisement

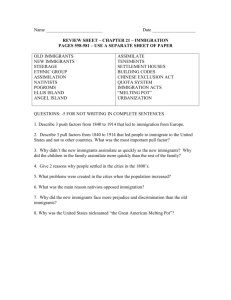

15 - Through Ellis Island and Angel Island: The Immigrant Experience Lazarus's poem suggests that the United States was a land of opportunity for the world's poor and downtrodden masses. By the 1880s, this had already been true for decades. Great waves of immigration had washed over the country since at least the 1840s. Some immigrants who chose to come to the United States were from Asia, Mexico, and Canada, but the vast majority crossed the Atlantic Ocean from Europe. They entered the country mainly through the port of New York City. From the 1840s until the 1890s, most of these Europeans came from northern and western Europe. Millions of Irish, British, Germans, and Scandinavians crossed the ocean to become Americans. In the late 1800s, however, immigration from southern and eastern Europe steadily increased. Italians, Greeks, Hungarians, Poles, and Russians began to dominate the steamship passenger lists. For all of these immigrants, the reasons for moving can be divided into push factors [push factor: a problem that causes people to immigrate to another place] and pull factors [pull factor: an attraction that draws immigrants to another place]. Push factors are problems that cause people to move, whereas pull factors are attractions that draw them to another place. Difficulties Push People from Europe Population growth and hunger were two major push factors that caused Europeans to emigrate, or leave their homeland. Much of Europe experienced rapid population growth in the 1800s. This growth resulted in crowded cities, a lack of jobs, and food shortages. Crop failures added to people's woes. Potato rot left many Irish starving in the 1840s. The Irish potato famine led to a wave of Irish emigration to the United States. In the late 1800s, many Jews in Europe faced persecution for their culture and beliefs. This hostility was very strong in Russia. The first Russian pogrom, or organized massacre of Jews, occurred in 1881. Attacks like this reflected a brutal anti-Semitism that caused more than a million Jews to leave Russia for the United States. Another push factor was scarcity of arable [arable: suitable for growing crops] land, or land suitable for growing crops. In the 1800s, mechanization of agriculture led to the growth of commercial farming on large tracts of land in Europe. In the process, common lands, traditionally available to all, were combined and enclosed by fences. Many peasants were suddenly thrown off the land and into poverty. Even families with large estates faced land shortages. In parts of Europe, landholdings were divided among all children at the death of their parents. After a few generations of such divisions, the resulting plots were too small to support a family. A hunger for land drove many Europeans across the Atlantic. Some immigrants planned to go to the United States, make their fortune, and return to their homelands. Others had no wish to go back. Many of those people emigrated because of the fourth major push factor: religious persecution. Russian and Polish Jews, for example, fled their villages to escape deadly attacks by people who abhorred their religion. Lazarus wrote her Statue of Liberty poem with this group of immigrants in mind. Lazarus had heard stories told by Jewish refugees from Russia. They described the pogroms [pogroms: organized anti-Jewish attacks that forced many Jews to leave Russia], or organized anti-Jewish attacks, that had forced them to leave their country. Armenian immigrants, many of them Catholics, told similar stories about persecution and massacres at the hands of Turks in the largely Muslim Ottoman Empire. Opportunities Pull Europeans to the United States Most European immigrants came to this country on steamships. The poorer ones crossed the Atlantic in steerage—the open space below the main deck that once housed the steering mechanism of sailing ships. Conditions there were so cramped that many passengers spent most of their time on deck.One of the great pull factors for European immigrants was the idea of life in a free and democratic society. They longed to live in a country where they had the opportunity to achieve their dreams. Less abstract, or more concrete, factors such as natural resources and jobs also exerted a strong pull. The United States had ample farmland, minerals, and forests. Germans, Scandinavians, and eastern Europeans brought their farming skills to the rolling hills and plains of the Midwest. They introduced new types of wheat and other grains that would help turn this region into the country's breadbasket. European immigrants also prospected for gold and silver. They mined iron and coal. They chopped down forests and sawed the trees into lumber. Booming industries offered jobs to unskilled workers, like the Irish, Italian, Polish, and Hungarian peasants who poured into the cities in the late 1800s. These new immigrants also worked on the ever-expanding rail system, sometimes replacing Irish and Chinese laborers. American railroad companies advertised throughout Europe. They offered glowing descriptions of the Great Plains, hoping to sell land they received as government grants. An even greater lure, however, came in the form of personal communications from friends and relatives who had already immigrated. Their letters back to the old country, known as America letters [America letters: letters from immigrants in the United States to friends and relatives in the old country, which spurred further immigration], might be published in newspapers or read aloud in public places. Sometimes the letters overstated the facts. Europeans came to think of the United States as the "land of milk and honey" and a place where the "streets are paved with gold." America letters helped persuade many people to immigrate to the United States. Improvements in Transportation Make Immigration Easier After the Civil War, most European immigrants crossed the Atlantic by steamship, a techno-logical advance over sailing ships. What had once been a three-month voyage now took just two weeks. Some passengers could afford cabins in the more comfortable upper decks of the ship. But most had to settle for steerage [steerage: the open area below a steamship's main deck, where most immigrants lived during the Atlantic crossing], the open area below the main deck. In steerage, hundreds of strangers were thrown together in huge rooms, where they slept in rough metal bunks. The rolling of the ship often made them ill. Seasickness, spoiled food, and filthy toilets combined to create an awful stench. During the day, steerage passengers crowded onto the main deck for fresh air. 15.3 The Ellis Island Immigration Station [Ellis Island Immigration Station: the port of entry for most European immigrants arriving in New York between 1892 and 1954], built in 1892 on a small piece of land in the harbor, was the port of entry for most European immigrants arriving in New York. Steerage passengers passed through a set of buildings staffed by officers of the Bureau of Immigration. This was a time of high anxiety for the immigrants. An array of officials would examine them closely to make sure they were fit to enter the country. Some of them would not pass inspection. Medical Inspections at Ellis Island Immigrants dreaded the eye examination because failure often meant being deported. Doctors lifted the immigrant’s eyelids for inspection. Some used their fingers, while others used tools such as a buttonhook. They looked for infection, especially the highly contagious disease trachoma, which could lead to blindness. Outside the main building at Ellis Island, officials attached an identification tag to each immigrant. The medical inspection began after the immigrants entered the building. Public Health Service doctors watched as people crossed through the baggage room and climbed the steep stairs to the enormous Registry Room, or Great Hall. This brief observation period became known as the "six-second exam." People who limped, wheezed, or otherwise showed signs of disease or disability would be pulled aside for closer inspection. In the Great Hall, the immigrants underwent a physical examination and an eye test. During the brief physical, the doctor checked for a variety of health problems, using chalk to mark the immigrant's clothing with a symbol for the suspected disease or other problem. For example, an L stood for lameness, an H meant a possible heart condition, and an X indicated a mental problem. Disabled individuals or those found to have incurable illnesses would face deportation [deportation: a forced return of immigrants to their home country], a forced return to their home country. The most dreaded mark was an E for eye condition. The doctor would check for trachoma, a contagious infection that could lead to blindness. Anyone with trachoma would certainly be rejected. In fact, this disease accounted for the most deportations by far. Legal Interviews in the Great Hall Along with receiving a medical exam, immigrants lined up for a legal interview. An inspector asked a series of questions to verify that immigrants could enter the country legally. Immigrants who passed the medical and legal tests would be free to go. Those who failed would be held for days, or even weeks, until their cases were decided. Immigrants with medical problems would be sent to a detention area. The rest got in line and slowly worked their way to the back of the Great Hall for the legal interview. One by one, they stood before the primary inspector, who usually worked with an interpreter. The inspector asked a list of 29 questions, starting with "What is your name?" It was once thought that many names were shortened or respelled at Ellis Island, but actually such changes were rare. Passenger lists, including the 29 questions and answers, were created at the port of departure in Europe. Immigrants provided their name, age, sex, race, marital status, occupation, destination, and other information. Steamship officials wrote the answers on the passenger list. In most cases, Ellis Island inspectors merely asked the questions again to verify that the answers matched those on the passenger list. The trickiest question was, "Do you have work waiting for you in the United States?" Those immigrants who wanted to show they were able to succeed in their new country sometimes answered yes. However, the Foran Act, a law passed by Congress in 1885, made it illegal for U.S. employers to import foreigners as contract laborers [contract laborer: an immigrant who signed a contract in Europe to work for an American employer, often to replace a striking worker]. The law's main purpose was to prevent the hiring of new immigrants to replace striking workers. Any immigrant who admitted to signing a contract to work for an employer in the United States could be detained. About 20 percent of immigrants failed either the medical examination or the legal interview. This does not mean they were denied entry. Those with treatable illnesses were sent to a hospital on Ellis Island for therapy. There they might stay for days or weeks until a doctor pronounced them fit. Other detained immigrants had to await a hearing in front of a Board of Special Inquiry. These immigrants stayed in dormitories on the second and third floors of the main building, sleeping in iron bunks that resembled those in steerage. The board members reviewed the details of each immigrant's case and listened to testimony from the detainee's friends and relatives, if any lived nearby. The board voted to accept almost all of the immigrants who came before it. In the end, about 2 percent of all immigrants were deported. Most of the immigrants who passed through Ellis Island spent a very short time undergoing medical and legal examination. Yet the whole process, including the waiting time, lasted for several agonizing hours. It ended with the legal interview. Immigrants who passed that final test were free to go. Relieved that the long ordeal was over, they boarded a ferry bound for New York City and a new life. Beyond Ellis Island: Life in the Cities Some new European immigrants quickly found their way to the farm country of the Midwest. However, the majority of the jobs were in the cities, so most immigrants stayed in New York or boarded trains bound for Boston, Cleveland, Chicago, or other industrial centers. As a result, urban populations exploded. From 1870 to 1920, the proportion of Americans who lived in cities jumped from about 25 percent to 50 percent.Newly arrived urban immigrants tended to live in the least desirable districts, where housing was cheapest. Such areas often contained the factories and shops that provided their livelihoods. Amid the city's din and dirt, immigrants crowded into tenement buildings and other run-down, slum housing. In 1914, an Italian immigrant described such an area of Boston: Here was a congestion the like of which I had never seen before. Within the narrow limits of one-half square mile were crowded together thirty-five thousand people, living tier upon tier, huddled together until the very heavens seemed to be shut out. These narrow alley-like streets of Old Boston were one mass of litter. The air was laden with soot and dirt. Ill odors arose from every direction . . . A thousand wheels of commercial activity whirled incessantly day and night, making noises which would rack the sturdiest of nerves.—Constantine M. Panunzio, The Soul of an Immigrant, 1969 Immigrants generally settled among others from their home country. They felt comfortable among people who spoke the same language, ate the same foods, and held the same beliefs. As a result, different areas of the city often had distinctive ethnic flavors. Jacob Riis, a writer and photographer, imagined a map of New York's ethnic communities. "A map of the city," he wrote in 1890, "colored to designate nationalities, would show more stripes than on the skin of a zebra, and more colors than any rainbow." 15.4 Immigrants typically came to the United States with little money and few possessions. Because of their general poverty and lack of education, most were not welcomed into American society. Without much support, they had to work hard to get ahead. In time, some saved enough to move out of the slums and perhaps even buy a home. A few opened small businesses, such as a grocery store or a tailor's shop. But many remained stuck in dangerous, low-wage factory jobs that barely paid their bills. An accident on the job or an economic downturn might leave them without work and possibly homeless and hungry. Immigrants Receive Aid from Several Sources In the late 1800s, the government did not provide aid or assistance to unemployed workers. They were expected to fend for themselves. But needy immigrants did have several places to turn for help. The first sources of aid were usually relatives or friends, who might provide housing and food.If necessary, the needy might seek assistance from an immigrant aid society. These ethnic organizations started as neighborhood social groups. They met mainly in churches and synagogues, groceries, and saloons—the centers of immigrant community life. They might pass the hat to collect money for a family in need. In time, local immigrant aid societies joined together to form regional and national organizations, such as the Polish National Alliance and the Sons of Italy in America. During the 1890s, a type of aid organization called a settlement house [settlement house: a community center that provided a variety of services to the poor, especially to immigrants] arose in the ethnic neighborhoods of many large cities. A settlement house was a community center that provided a variety of services to the poor, especially to immigrants. It might offer daytime care for children, as well as classes, health clinics, and recreational opportunities for the entire community. Opponents of immigration claimed that the “garbage” of Europe was being dumped on American shores. Political parties included anti-immigration statements in their platforms. For example, in 1892 the Democratic Party said the country should not become “the dumping ground for the known criminals and professional paupers of Europe.” Immigrants might also turn to political bosses [political bosses: powerful leaders who ran local politics in many cities, providing jobs and social services to immigrants in exchange for political support] for help. These bosses were powerful leaders who ran local politics in many cities. They were in a position to provide jobs and social services to immigrants in exchange for the political support of immigrants who could vote. These supporters often voted for the boss and his slate of candidates in local elections. The Assimilation of Immigrants Many immigrants held on to their old customs and language as they gradually adapted to American life. This was especially true for older immigrants living in ethnic neighborhoods. The children of immigrants, however, typically found assimilation into American society much easier than their parents did. Education was the main tool of assimilation. Immigrant children in public schools studied American history and civics, and they learned to speak English. Yearning to fit in, they more eagerly adopted American customs. Some patriotic organizations pushed for the Americanization [Americanization: the assimilation of immigrants into American society, a goal of some patriotic groups who feared that increased immigration threatened American society and values] of immigrants, fearing that increased immigration posed a threat to American values and traditions. Through efforts such as the publishing of guides for new citizens, they promoted loyalty to American values. Some Americans Reject Immigrants Many Americans disliked the recent immigrants, in part because of religious and cultural differences. Most of the earlier immigrants were Protestants from northern Europe. Later waves of immigrants came from southern and eastern Europe and were often Catholics or Jews. Their customs seemed strange to Americans of northern European ancestry, who often doubted that these more recent immigrants could be Americanized. Many people also blamed them for the labor unrest that had spread across the country in the late 1800s. They especially feared that foreign anarchists and socialists might undermine American democracy. Dislike and fear provoked demands to limit immigration and its impact on American life. This policy of favoring the interests of native-born Americans over those of immigrants is called nativism [nativism: the policy of favoring the interests of native-born Americans over those of immigrants]. Nativism had a long history in the United States. Before the Civil War, nativists had opposed the immigration of Irish Catholics. In the 1850s, they formed a secret political party known as the KnowNothings, because when asked a question about the group, members were told to answer, "I don't know." As the main source of immigration shifted to southern and eastern Europe in the late 1800s, nativism flared up again. Nativists were not only bothered by religious and cultural differences, but also saw immigrants as an economic threat. Native workers worried that immigrants were taking their jobs and lowering wages. Immigrants often worked for less money and sometimes served as scabs, replacement workers during labor disputes.In 1894, a group of nativists founded the Immigration Restriction League. This organization wanted to limit immigration by requiring that all new arrivals take a literacy test to prove they could read and write. In 1897, Congress passed such a bill, but the president vetoed it. Twenty years later, however, another literacy bill became law. Meanwhile, efforts to slow immigration continued. During the 1920s, Congress began passing quota laws to restrict the flow of European immigrants into the United States. 15.5 Although immigration after the Civil War was mainly from Europe, many immigrants also arrived each year from Asia. They made important contributions to the country. They also provoked strong reactions from nativists. Chinese Immigrants Seek Gold Mountain You have read about the thousands of Chinese railroad workers who laid track through the Sierra Nevada for the Central Pacific Railroad. Thousands more joined the swarms of prospectors who scoured the West for gold. In fact, the Chinese referred to California, the site of the first gold rush, as Gold Mountain.The vast majority of Chinese immigrants were men. They streamed into California, mainly through the port of San Francisco. Most expected to work hard and return home rich. However, they usually ended up staying in the United States. Besides finding employment in mining and railroad construction, Chinese immigrants worked in agriculture. Some had first come to Hawaii as contract laborers to work on sugar plantations. There they earned a reputation as reliable, steady workers. Farm owners on the mainland saw the value of their labor and began bringing the Chinese to California. The Chinese were willing to do the "stoop labor" in the fields that many white laborers refused to do. By the early 1880s, most harvest workers in the state were Chinese.Many businesses hired the Chinese because they were willing to work for less money. This allowed owners to reduce production costs even further by paying white workers less. As a result, friction developed between working-class whites and Chinese immigrants. The Exclusion Act: Shutting the Doors on the Chinese During the 1870s, a depression and drought knocked the wind out of California's economy. Seeking a scapegoat, many Californians blamed Chinese workers for their economic woes. The Chinese made an easy target. They looked different from white Americans, and their language, religion, and other cultural traits were also very different. As a result, innocent Chinese became victims of mob violence, during which many were driven out of their homes and even murdered. Anti-Chinese nativism had a strong racial component. The Chinese were seen as an inferior people who could never be Americanized. Economist Henry George reflected this racist point of view in characterizing the Chinese as "utter heathens, treacherous, sensual, cowardly, cruel." Nativists demanded that Chinese immigration be curtailed, or reduced. Their outcries led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act [Chinese Exclusion Act: an 1882 law prohibiting immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years and preventing Chinese already in the country from becoming citizens; the first U.S. immigration restriction based solely on nationality or race] in 1882. This law prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers, skilled or unskilled, for a period of 10 years. It also prevented Chinese already in the country from becoming citizens. For the first time, the United States had restricted immigration based solely on nationality or race. The Chinese Exclusion Act still allowed a few Chinese to enter the country, including merchants, diplomats, teachers, students, and relatives of existing citizens. But the act did what it was supposed to do. Immigration from China fell from a high of nearly 40,000 people in 1882 to just 279 two years later.Starting in 1910, immigration officials processed Asian immigrants at Angel Island in San Francisco Bay. Some newcomers faced lengthy detention. Here a Chinese immigrant endures a legal interview. Angel Island: The Ellis Island of the West Although the Chinese Exclusion Act was highly effective, some Chinese managed to evade the law by using forged documents and false names. In response, federal officials developed tougher procedures for processing Asian immigrants. They also decided to replace the old immigrant-processing center in San Francisco with a new, more secure facility located on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay. Completed in 1910, the Angel Island Immigration Station [Angel Island Immigration Station: the port of entry for most Asian immigrants arriving in San Francisco between 1910 and 1940] became known as the "Ellis Island of the West." It was designed to enforce the exclusion act by keeping new Chinese arrivals isolated from friends and relatives on the mainland and preventing them from escaping. At Angel Island, immigrants underwent a thorough physical exam. Then they faced an intense legal interview, more involved and detailed than the Ellis Island version. Officials hoped to exclude Chinese who falsely claimed to be related to American citizens. Interviewers asked applicants specific questions about their home village, their family, and the house they lived in. They also questioned witnesses. The process could take days. Those who failed the interviews could enter an appeal, but additional evidence took time to gather. Applicants were often detained for weeks, months, or even years. Chinese detained at Angel Island stayed locked in wooden barracks. These living quarters were crowded and unsanitary. Detainees felt miserable and frustrated to be stopped so close to their goal. From their barracks, they could see across the water to the mainland. Some carved poems onto the walls to express their feelings. One Chinese detainee wrote, Imprisoned in the wooden building day after day, My freedom withheld; how can I bear to talk about it? —from Ronald Takaki, Strangers from a Different Shore, 1989 Many Chinese never made it to the mainland. About 10 percent were put on ships and sent back to China after failing the medical exam or legal interview. Other Asian Groups Immigrate to the United States The Chinese Exclusion Act created a shortage of farm laborers. Large-scale farmers looked to Japan and later to Korea and the Philippines for workers. These other Asian immigrants had experiences similar to those of the Chinese. Many first emigrated to work on Hawaiian sugar plantations. They came to the United States through Angel Island to work in orchards, in vineyards, and on farms in California, Oregon, and Washington. Some worked for railroads and other industries. A number of Japanese immigrants leased farmland and had great success growing fruits and vegetables. They formed ethnic neighborhoods that provided for their economic and social needs. Koreans had less success. Only a small number moved from Hawaii to the mainland in the early 1900s, and they led more isolated lives. Immigrants from the Philippines migrated up and down the West Coast, taking part in fruit and vegetable harvests. In the winter, many of these Filipinos worked in hotels and restaurants. Despite their contributions, all Asian immigrants faced prejudice, hostility, and discrimination. In 1906, anti-Asian feelings in San Francisco caused the city to segregate Asian children in separate schools from whites. When Japan's government protested, President Theodore Roosevelt got involved. Hoping to avoid offending East Asia's most powerful nation, the president persuaded San Francisco's school board to repeal the segregation order. In return, he got a pledge from Japan to discuss issues related to immigration. In 1907 and 1908, the American and Japanese governments carried out secret negotiations through a series of notes. These notes became known as the Gentlemen's Agreement. In the end, Japanese officials agreed not to allow laborers to emigrate to the United States. They did, however, insist that wives, children, and parents of Japanese in the United States be allowed to immigrate. Immigration has always been an important part of American life. Immigrants helped to populate and settle the United States. They have played a key role in shaping our history and culture. These newcomers arrived in the United States in 1920, the last year of unrestricted immigration from Europe. In 1921, Congress passed the first of a series of laws designed to reduce immigration into the country. These laws used quotas to limit the total number of immigrants as well as the number of people allowed to enter from any one country. Since 1820, immigration to the United States has come in three great waves, or surges. The first wave, from 1820 to around 1870, came mostly from northern and western Europe. The second wave, from about 1880 to 1920, included people from all parts of world, but especially southern and eastern Europe. A third great wave began in 1965 and continues today. You can see these waves on the graph. These ebbs and flows of immigration reflect many factors. Immigration policy, for instance, has had a huge impact. In the early 1920s, laws were passed that severely limited immigration from most parts of the world. They remained in effect for over 40 years. Major wars have also had a chilling effect on immigration. So have economic downturns, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s.Changes in immigration policy in 1965 triggered the last great wave of immigration. By 2003, the number of foreign-born people living in the United States rose to 33 million, nearly 12 percent of the population. Like earlier immigrants, the most recent newcomers are raising questions about how we define ourselves as a people and a nation.