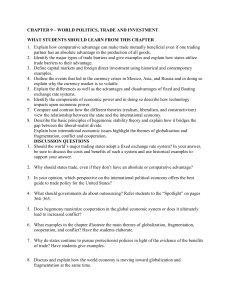

Introductory Essay - Bessie B. Moore Center for Economic Education

advertisement