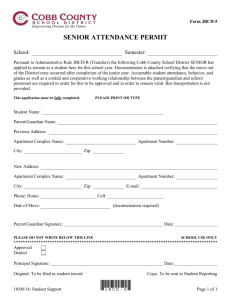

As the Mountaintops Fall, a Coal Town Vanishes

advertisement

Association of EnergyEngineers New York Chapter www.aeeny.org May 2011 Newsletter Part 1 52 Years and $750 Million Prove Einstein Was Right By Dennis Overbye, NYTimes, May 4, 2011 NASA An artist’s conception of Gravity Probe B orbiting Earth to measure space-time IN A TOUR DE FORCE OF TECHNOLOGY and just plain stubbornness spanning half a century and costing more than $750 million, a team of experimenters from Stanford University reported on Wednesday that a set of orbiting gyroscopes had detected a slight sag and an even slighter twist in space-time. The finding confirms some of the weirdest of the many strange predictions — like black holes and the expanding universe — of Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity, general relativity. “We have completed this landmark experiment of testing Einstein’s universe,” Francis Everitt, leader of the project, known as Gravity Probe B, said at a news conference at NASA headquarters in Washington. “And Einstein survives.” That was hardly a surprise. Observations of planets, the Moon and particularly the shifting orbits of the Lageos research satellites had convinced astronomers and physicists that Einstein’s predictions were on the mark. Nevertheless, scientists said that the Gravity Probe results would live forever in textbooks as the most direct measurements, and that it was important to keep testing theories that were thought to be correct. Clifford M. Will of Washington University in St. Louis — who was not part of the team but was chairman of a National Aeronautics and Space Administration advisory committee evaluating its work, and who wrote a book titled “Was Einstein Right?” — said that in science, “no such book is ever closed.” Einstein’s theory relates gravity to the sagging of cosmic geometry under the influence of matter and energy, the way a sleeper makes a mattress sag. One consequence is that a massive spinning object like Earth should spin up the empty space around it, the way twirling the straw in a Frappuccino sets the drink and the whole Venti-size cup spinning around with it, an effect called frame dragging. Astronomers think this effect, although minuscule for Earth, could play a role in the black hole dynamos that power quasars. Empty space in the vicinity of Earth is indeed turning, Dr. Everitt reported at the news conference and in a paper prepared for the journal Physical Review Letters, at the leisurely rate of 37 one-thousandths of a second of arc — the equivalent of a human hair seen from 10 miles away — every year. With an uncertainty of 19 percent, that measurement was in agreement with Einstein’s predictions of 39 milliarcseconds. Likewise, the “sag” should alter the space-time geometry around Earth, warping it from the Euclidean ideal and cutting an inch out of the Gravity Probe’s orbit around it, so that the circumference is slightly less than the Euclidean ideal of pi times the orbit’s diameter, a fact confirmed by the Stanford gyroscopes to an accuracy of 0.3 percent. For Dr. Everitt, who joined the Gravity Probe experiment in 1962 as a young postdoctoral fellow and has worked on nothing else since, the announcement on Wednesday capped a careerlong journey. The experiment was conceived in 1959, but the technology to make these esoteric measurements did not yet exist, which is why the experiment took so long and cost so much. The gyroscopes, for example, were made of superconducting niobium spheres, the roundest balls ever manufactured, which then had to be flown in a lead bag to isolate them from any other influences in the universe, save the subversive curvature of space-time itself. Shortly before the probe’s launching, Dr. Francis said the project had been canceled at least seven times, “depending on what you mean by canceled.” It was finally sent into orbit in 2004 and operated for some 17 months, but not all went well. When the scientists began analyzing their data, they discovered that patches of electrical charge on the niobium balls had generated extra torque on the gyroscopes, causing them to drift. It would take five more years to understand the spurious signals and retrieve the gravity data by dint of an effort that Dr. Will called “nothing less than heroic.” In the meantime, the NASA grant ran out. Dr. Everitt secured another one from Richard Fairbank, a financier and son of one of the experiment’s founders, William Fairbank, that was matched by NASA and Stanford. When that ran out and NASA turned him down for a new grant, Dr. Everitt obtained a $2.7 million grant from Turki al-Saud, a Stanford graduate and vice president for research institutes at the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia. ### Current NY Chapter AEE Sponsors: New York Chapter of AEE thanks our corporate sponsors who help underwrite our activities. Please take a moment to visit their websites and learn more about them: Association for Energy Affordability Constellation Energy Donnelly Mechanical Corp Duane Morris Innoventive Power LessOil Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Parsons Brinckerhoff If you or your firm is interested in sponsoring the New York Chapter of AEE, please contact Jeremy Metz at jeremy.metz@verizon.com. Warren Buffett, Delegator in Chief By Andrew Ross Sorkin, NYTimes, April 23, 2011 “He picked the chorus line but didn’t attempt to dance.” John Cuneo Warren Buffett THAT IS WARREN BUFFETT’S MANAGEMENT STYLE, as described in a biography by Roger Lowenstein. Mr. Buffett delegates; he empowers his executives. Mr. Buffett, the 80-yearold chief executive of Berkshire Hathaway known as Uncle Warren, has been praised as one of the world’s greatest business managers. He has racked up average annualized returns of more than 20 percent for four decades. Yet in a potential case study for business schools, the question is now being asked: Does Mr. Buffett delegate too much? Just in time for his company’s annual meeting with 35,000 investors next weekend, Mr. Buffett’s management style is coming under scrutiny. His heir apparent, David L. Sokol, resigned last month after it emerged that he had bought $10 million worth of stock in Lubrizol, a chemical manufacturer, a day after he began orchestrating a merger with Berkshire, which later acquired Lubrizol for $9 billion — increasing the value of Mr. Sokol’s holding by $3 million. Although Mr. Sokol mentioned that he was a shareholder in Lubrizol to Mr. Buffett when he suggested that Berkshire buy the company, Mr. Buffett said he did not ask about “the date of his purchase or the extent of his holdings.” The controversy exposed a paradox: Mr. Buffett may be considered one of the world’s best managers, but he doesn’t actively manage the hundreds of businesses that Berkshire owns. “Did Sokol’s actions reveal shortcomings in the company’s governance system that need to be addressed?” asked Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business in a paper titled “The Resignation of David Sokol: Mountain or Molehill for Berkshire Hathaway?” Unlike Jeffrey R. Immelt, the chief executive of General Electric, who spends much of his time on airplanes traveling the world to visit the company’s 287,000 employees and oversees a giant campus and management team in Fairfield, Conn., Mr. Buffett “manages” Berkshire’s 257,000 employees with just 21 people at his headquarters in a small office in Omaha. Mr. Buffett’s business partner, Charles Munger, once described Mr. Buffett’s day. He spends half of his time just sitting around and reading, Mr. Munger said. “And a big chunk of the rest of the time is spent talking one on one, either on the telephone or personally, with highly gifted people whom he trusts and who trust him.” And that trust has advantages. “Part of his genius is that he’s created a hands-off culture that encourages entrepreneurs to sell their private companies to Berkshire,” said Larry Pitkowsky, managing partner of GoodHaven Capital Management and a longtime Berkshire shareholder, “and, critically, that they keeping showing up for work every day without worrying that they are going to get a call from headquarters telling them how to run things.” How handsoff is Mr. Buffett? When questioned once about why Berkshire didn’t take a more active role in fixing Moody’s, the troubled credit rating agency, in which he was the largest shareholder, he declared: “I’ve never been to Moody’s. I don’t even know where they’re located.” “If I thought they needed me I wouldn’t have bought the stock,” he added. He sees himself less of an activist than as a passive investor, a stock picker with a nose for a good deal. “We don’t tell Burlington Northern what safety procedures to put in or AmEx who they should lend to,” he said at his annual meeting two years ago. “When we own stock, we are not there to try and change people.” His management approach may be as much a function of his own philosophy as it is a practical preference. He likes to make his investments dispassionately, based on the numbers, rather than let emotions get involved. Mr. Buffett’s investing antennas may be genius, but some of his critics have suggested that his trust-based management style may have left him too farsighted to quickly spot operational problems. As reported by Carol Loomis of Fortune magazine, when Mr. Buffett was first told in 1991 about indications of a possible scandal at Salomon Brothers that later nearly took down the company (Berkshire was its largest shareholder), he initially did not detect any reason to be particularly alarmed, “so he went back to dinner.” Only after speaking several days later about the matter with his partner, Mr. Munger, “did Buffett get a sense of real trouble.” ### A 21stCentury Water Forecast By Felicity Barringer, NYTimes, Apr 25 2011 The broadbrush conclusion of a new federal report on the future impact of climate change on water in the West is a bit familiar. Throughout the West, there will be less snow, and what snow there is will melt faster. The dry Southwest is going to get drier, and the wet Northwest wetter, as a diagram in the report (above) shows. The 122-page report includes original research — “including state-of-the-art climate modeling,” as Interior Secretary Ken Salazar said during a conference call on Monday — but also harks back to peer-reviewed scientific literature on seven river basins: the Columbia, the Klamath, the Sacramento-San Joaquin, the Colorado, the Missouri, the Truckee and the Rio Grande. The report, jointly produced by the Bureau of Reclamation and the Army Corps of Engineers, offers not just some interesting details on individual basins but a revealing window on how the administration of President Obama, who did not even mention climate change in his last State of the Union address, deals with the subject in general. The report and the conference call send a clear message: the West is getting warmer, and while the effects vary depending on geography, the places that are feeling water stress now are going to feel more in the future because snow will melt faster, bringing a decline in summertime stream flows. And as Mr. Salazar observed on Monday, this reordering of natural water supplies “will mean significant potential dislocations to the economy and the environment.” The focus is largely on the impact of climate change, not the cause; the role of greenhouse gases is mentioned in a by-the-way context, in sentences like this: “It is widely accepted that water demand changes will occur due to increased air temperatures, increased greenhouse gas concentrations and changes in precipitation, winds, humidity, and atmospheric aerosol and ozone levels.” This could be a coincidence or an early indication of a new administration strategy: deal with the immediate and palpable causes of climate change, like water scarcity, first, and then tackle the overall problem later. Certainly Mr. Salazar and two subordinates, Anne Castle, the assistant secretary for water and science, and Michael L. Connor, the commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, were intent on using the report, delivered in response to a 2009 Congressional mandate, to create or bolster a sense of urgency among Western water managers who are planning for the future. For instance, while Mr. Salazar said there would be no change in nearly 80 years of compacts and court decisions that make up the what Colorado River water users call “The Law of the River,” he pointed out that the seven states and the federal government, joint managers of that system, “must realize that “on top of that already oversubscribed system you are looking at significant decreases in water supply.” The report also had warnings for other river basins, noting for example that while the Upper Missouri River could expect a greater inflow of water over all in 60 to 80 years, the South Fork of the Platte River, on which the water-stressed city of Denver depends, is likely to get less. And while the Columbia River system should be handling more runoff or snow melt over all in the future, in the low-flow summer months, “annual minimum-week runoff is projected to steadily decrease. Lower instream flows and increased summer air temperatures may result in warmer channel flow and possibly significant impacts on aquatic species and those species dependent on them.” For the Rio Grande system, like the Colorado’s, the news is mostly bad for economies and environments that depend on readily available water. Runoff will increase when it is less needed, from December to March, and decrease in the April-July period when the need is far greater. ### ▼ As the Mountaintops Fall, a Coal Town Vanishes Nicole Bengiveno/The New York Times Quinnie Richmond's house is nearly all that remains of Lindytown, West Virginia . By Dan Barry, NYTimes, April 12, 2011 LINDYTOWN, W.Va. Along Route 26 in Boone County, W.Va., there are signs of mining activity, including a loadout facility, where coal is crushed and loaded on trucks and rail cars. To reach a lost American place, here just a moment ago, follow a thin country road as it unspools across an Appalachian valley’s grimy floor, past a coal operation or two, a church or two, a village called Twilight. Beware of the truck traffic. Watch out for that car-chasing dog. After passing an abandoned union hall with its front door agape, look to the right for a solitary house, tidy, yellow and tucked into the stillness. This is nearly all that remains of a West Virginia community called Lindytown. In the small living room, five generations of family portraits gaze upon Quinnie Richmond, 85, who has trouble summoning the memories, and her son, Roger, 62, who cannot forget them: the many children all about, enough to fill Mr. Cook’s school bus every morning; the Sunday services at the simple church; the white laundry strung on clotheslines; the echoing clatter of evening horseshoes; the sense of home. But the coal that helped to create Lindytown also destroyed it. Here was the church; here was its steeple; now it’s all gone, along with its people. Gone, too, are the surrounding mountaintops. To mine the soft rock that we burn to help power our light bulbs, our laptops, our way of life, heavy equipment has stripped away the trees, the soil, the rock — what coal companies call the “overburden.” Now, the faint, mechanical beeps and grinds from above are all that disturb the Lindytown quiet, save for the occasional, seam-splintering blast. A couple of years ago, a subsidiary of Massey Energy, which owns a sprawling mine operation behind and above the Richmond home, bought up Lindytown. Many of its residents signed Massey-proffered documents in which they also agreed not to sue, testify against, seek inspection of or “make adverse comment” about coal-mining operations in the vicinity. You might say that both parties were motivated. Massey preferred not to have people living so close to its mountaintop mining operations. And the residents, some with area roots deep into the 19th century, preferred not to live amid a dusty industrial operation that was altering the natural world about them. So the Greens sold, as did the Cooks, and the Workmans, and the Webbs ... But Quinnie Richmond’s husband, Lawrence — who died a few months ago, at 85 — feared that leaving the home they built in 1947 might upset his wife, who has Alzheimer’s. He and his son Roger, a retired coal miner who lives next door, chose instead to sign easements granting the coal company certain rights over their properties. In exchange for also agreeing not to make adverse comment, the two Richmond households received $25,000 each, Roger Richmond recalls. “Hush money,” he says, half-smiling. As Mr. Richmond speaks, the mining on the mountain behind him continues to transform, if not erase, the woodsy stretches he explored in boyhood. It has also exposed a massive rock that almost seems to be teetering above the Richmond home. Some days, an anxious Mrs. Richmond will check on the rock from her small kitchen window, step away, then come back to check again. And again. A Dictator of Destiny Here in Boone County, coal rules. The rich seams of bituminous black have dictated the region’s destiny for many generations: through the advent of railroads; the company-controlled coal camps; the bloody mine wars; the increased use of mechanization and surface mining, including mountaintop removal; the related decrease in jobs. The county has the largest surface-mining project (the Massey operation) in the state and the largest number of coal-company employees (more than 3,600). Every year it receives several million dollars in tax severance payments from the coal industry, and every June it plays host to the West Virginia Coal Festival, with fireworks, a beauty pageant, a memorial service for dead miners, and displays of the latest mining equipment. Without coal, says Larry V. Lodato, the director of the county’s Community and Economic Development Corporation, “You might as well turn out the lights and leave.” In recent years, surface mining has eclipsed underground mining as the county’s most productive method. This includes mountaintop removal — or, as the industry prefers to call it, mountaintop mining — a now-commonplace technique that remains startling in its capacity to change things. Various government regulations require that coal companies return the stripped area to its “approximate original contour,” or “reclaim” the land for development in a state whose undulating topography can thwart plans for even a simple parking lot. As a result, the companies often dump the removed earth into a nearby valley to create a plateau, and then spray this topsyturvy land with seed, fertilizer and mulch. The coal industry maintains that by removing some mountaintops from the “Mountain State,” it is creating developable land that makes the state more economically viable. State and coal officials point to successful developments on land reclaimed by surface mining, developments that they say have led to the creation of some 13,000 jobs. But Ken Ward Jr., a reporter for The Charleston Gazette, has pointed out that two-fifths of these jobs are seasonal or temporary; a third of the full-time jobs are at one project, in the northern part of the state; and the majority of the jobs are far from southern West Virginia, where most of the mountaintop removal is occurring, and where unemployment is most dire. In Boone County, development on reclaimed land has basically meant the building of the regional headquarters for the county’s dominant employer — Massey Energy. And with reclamation, there is also loss. “I’m not familiar at all with Lindytown,” says Mr. Lodato, the county’s economic development director. “I know it used to be a community, and it’s close to Twilight.” A Fighter About 10 miles from Lindytown, outside a drab convenience store in the unincorporated town of Van, a rake-thin woman named Maria Gunnoe climbs into a maroon Ford pickup that is adorned with a bumper sticker reading: “Mountains Matter — Organize.” The daughter, granddaughter and sister of union coal miners, Ms. Gunnoe is 42, with sorrowful dark eyes, long black hair and a desire to be on the road only between shift changes at the local mining operations — and only with her German shepherd and her gun. Less than a decade ago, Ms. Gunnoe was working as a waitress, just trying to get along, when a mountaintop removal operation in the small map dot of Bob White disrupted her “home place.” It filled the valley behind her house, flooded her property, contaminated her well and transformed her into a fierce opponent of mountaintop removal. Through her work with the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition, she has become such an effective environmental advocate that in 2009 she received the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize. But no one threw a parade for her in Boone County, where some deride her as anti-coal; that is, anti-job. Ms. Gunnoe turns onto the two-lane road, Route 26, and heads toward the remains of Lindytown. On her right stands Van High School, her alma mater, where D. Ray White, the gifted and doomed Appalachian dancer, used to kick up his heels at homecomings. On her left, the community center where dozens of coal-company workers disrupted a meeting of environmentalists back in 2007. “There was a gentleman who pushed me backward, over my daughter, who was about 12 or 13, and crying,” Ms. Gunnoe later recalls. “I pushed him back, and he filed charges against me for battery. He was 250 pounds, and I had a broken arm.” A jury acquitted her within minutes. Ms. Gunnoe drives on. Past the long-closed Grill bar, its facade marred by graffiti. Past an out-of-context clot of land that rises hundreds of feet in the air — “a valley fill,” she says, that has been “hydroseeded” with fast-growing, non-native plants to replace the area’s lost natural growth: its ginseng root, its goldenseal, it hickory and oak, maple and poplar, black cherry and sassafras. “And it will never be back,” she says. Ms. Gunnoe has a point. James Burger, a professor emeritus of forestry and soil science at Virginia Tech University, said the valley fill process often sends the original topsoil to the bottom and crushed rock from deeper in the ground to the top. With the topography and soil properties altered, Dr. Burger says, native plants and trees do not grow as well. “You have hundreds of species of flora and fauna that have acclimated to the native, undisturbed conditions over the millennia,” he says. “And now you’re inverting the geologic profile.” Dr. Burger says that he and other scientists have developed a reclamation approach that uses native seeds, trees, topsoil and selected rock material to help restore an area’s natural diversity, at no additional expense. Unfortunately, he says, these methods have not been adopted in most Appalachian states, including West Virginia. Past a coal operation called a loadout, an oversized Tinker Toy structure where coal is crushed and loaded on trucks and rail cars. Past the house cluster called Bandytown, home of Leo Cook, 75, the former school bus driver who once collected Roger Richmond and the other kids from Lindytown, where he often spent evenings at a horseshoe pit, now overgrown. “We got to have coal,” says Mr. Cook, a retired miner. “What’s going to keep the power on? But I believe with all my heart that there’s a better way to get that coal.” Ms. Gunnoe continues deeper into the mud-brown landscape, where the fleeting appearance of trucks animates the flattened mountaintops. On her right, a dark, winding stream damaged by mining; on her left, several sediment-control ponds that filter out pollutants from the runoff of mining operations. Past the place called Twilight, a jumble of homes and trailers, where the faded sign of the old Twilight Super Market still promises Royal Crown Cola for sale. Soon she passes the abandoned hall for Local 8377 of the United Mine Workers of America, empty since some underground mining operations shut down a couple of decades ago. Its open door beckons you to examine the papers piled on the floor: a Wages, Lost Time, and Expense Voucher booklet from 1987; the burial fund’s bylaws; canceled checks bearing familiar surnames. On, finally, to Lindytown. The Company Line According to a statement from Shane Harvey, the general counsel for Massey, this is what happened: Many of Lindytown’s residents were either retired miners or their widows and descendants who welcomed the opportunity to move to places more metropolitan or with easier access to medical facilities. Interested in selling their properties, they contacted Massey, which began making offers in December 2008 — offers that for the most part were accepted. “It is important to note that none of these properties had to be bought,” Mr. Harvey said. “The entire mine plan could have been legally mined without the purchase of these homes. We agreed to purchase the properties as an additional precaution.” When asked to elaborate, Mr. Harvey responded, in writing, that Massey voluntarily bought the properties “as an additional backup to the state and federal regulations” that protect people who live near mining operations. James Smith, 68, a retired coal miner from Lindytown, says the company’s statement is true, as far as it goes. Yes, Lindytown had become home mostly to retired union miners and their families; when the Robin Hood No. 8 mine shut down, for example, his three sons had to leave the state to work. And yes, some people approached Massey about selling their homes. But, Mr. Smith says, many residents wanted to leave Lindytown only because the mountaintop operations above had ruined the quality of life below. His family went back generations here. He married a local woman, raised kids, became widowed and married again. A brother lived in one house, a sister lived in another, and nieces, nephews and cousins were all around. And there was this God-given setting, where he could wander for days, hunting raccoon or searching for ginseng. But when the explosions began, dust filled the air. “You could wash your car today, and tomorrow you could write your name on it in the dust,” he says. “It was just unpleasant to live in that town. Period.” Massey was a motivated buyer, he argues, given that it was probably cheaper to buy out a small community than to deal with all the complaint-generated inspections, or the possible lawsuits over silica dust and “fly rock.” “Hell, what they paid for that wasn’t a drop in the bucket,” he says. Massey did not elaborate on why it bought out Lindytown, though general concerns about public health have been mounting. In blocking another West Virginia mountaintop-removal project earlier this year, the Environmental Protection Agency cited research suggesting that health disparities in the Appalachian region are “concentrated where surface coal mining activity takes place.” In the end, Mr. Smith says, he would not be living 150 miles away, far from relations and old neighbors, if mountaintop removal hadn’t ruined Lindytown. “You might as well take the money and get rid of your torment,” he says, adding that he received more than $300,000 for his property. “After they destroyed our place, they done us a favor and bought it.” Memories, What’s Left Ms. Gunnoe pulls up to one of the last houses in Lindytown, the tidy yellow one, and visits with Quinnie and Roger Richmond. He uses his words to re-animate the community he knew. For many years, his grandfather was the preacher at the small church down the road, where the ringing of a bell gave fair warning that Sunday service was about to begin. And his grandmother lived in the house still standing next door; she toiled in her garden well past 100, growing the kale, spinach and mustard greens that she loved so much. His father, Lawrence, joined the military in World War II after his older brother, Carson, was killed in Sicily. He returned, married Quinnie, and built this house. Before long, he became a section foreman in the mines, beloved by his men in part because of Quinnie’s fried-apple pies. After graduating from Van High School — that’s his senior photograph, there on the wall — Roger Richmond followed his father into the mines. He married, had children, divorced, made do when the local mine shut down, eventually retired and, in 2001, set up his mobile home beside his parents’ house. By now, things had changed. With the local underground mine shut down, there were nowhere near as many jobs, or kids. And this powder from the mountaintops was settling on everything, turning to brown paste in the rain. People no long hung their whites on the clotheslines. Soon, rumors of buyouts from Massey became fact, as neighbors began selling and moving away. “Some of them were tired of fighting it,” Mr. Richmond says. “Of having to put up with all the dust. Plus, you couldn’t get out into the hills the way you used to.” One example. Mr. Richmond’s Uncle Carson, killed in World War II, is buried in one of the small cemeteries scattered about the mountains. If he wanted to pay his respects, in accordance with government regulations for active surface-mining areas, he would have to make an appointment with a coal company, be certified in work site safety, don a construction helmet and be escorted by a coal-company representative. In the end, the Richmonds decided to sell various land rights to Massey, but remain in Lindytown, as the homes of longtime neighbors were boarded up and knocked down late last year, and as looters arrived at all hours of the day to steal the windows, the wiring, the pillars from Elmer Smith’s front porch — even the peaches, every one of them, growing from trees on the Richmond property. “They was good peaches, too,” says Mr. Richmond. “I like peaches,” says his mother. Would Lindytown have died anyway? Would it have died even without the removal of its surrounding mountaintops? These are the questions that Bill Raney, the president of the West Virginia Coal Association, raises. Sometimes, he says, depopulation is part of the natural order of things. People move to be closer to hospitals, or restaurants, or the Wal-Mart. There is also that West Virginia truism, he adds: “When the coal’s gone, you go to where the next coal seam is.” Of course, in the case of Lindytown, the coal is still here; it’s the people who are mostly gone. Now, when darkness comes to this particular hollow, you can see a small light shining from the kitchen window of a solitary, yellow house — and, sometimes, a face, peering out. ### Sardine Life What a century and a half of piled-up housing reveals about us. By Justin Davidson , New York, Apr 3 2011 ▼ (Photo: Charles Harbutt/Courtesy of Laurence Miller Gallery, New York) New York didn’t invent the apartment. Shopkeepers in ancient Rome lived above the store, Chinese clans crowded into multistory circular tulou, and sixteenth-century Yemenites lived in the mud-brick skyscrapers of Shibam. But New York re-invented the apartment many times over, developing the airborne slice of real estate into a symbol of exquisite urbanity. Sure, we still have our brownstones and our townhouses, but in the popular imagination today’s New Yorker occupies a glassed-in aerie, a shared walk-up, a rambling prewar with walls thickened by layers of paint, or a pristine white loft. The story of the New York apartment is a tale of need alchemized into virtue. Over and over, the desire for better, cheaper housing has become an instrument of urban destiny. When we were running out of land, developers built up. When we couldn’t climb any more stairs, inventors refined the elevator. When we needed much more room, planners raised herds of towers. And when tall buildings obscured our views, engineers took us higher still. This architectural evolution has roughly tracked the city’s financial fortunes and economic priorities. The turn-of-the-century Park Avenue duplex represented the apotheosis of the plutocrat; massive postwar projects like Stuyvesant Town embodied the national mid-century drive to consolidate the middle class; and the thin-air penthouses of Trump World Tower capture the millennial resurgence of buccaneering capitalism. You can almost chart income inequality over the years by measuring the height of New York’s ceilings. The apartment was not always the basic unit of Manhattan life. To the refined nineteenthcentury New Yorker, the idea of being confined to a single floor, with strangers stomping above and lurking below, was an intolerable horror, fit for greenhorns and laborers. Even circa 1900, Edith Wharton’s socially sensitive anti-heroine Lily Bart in The House of Mirth has strong opinions about what sort of female belongs in a flat, instead of a proper house: “Oh, governesses—or widows. But not girls!” It took decades to cajole respectable New Yorkers out of their single-family homes. In 1857, Calvert Vaux, who later became Frederick Law Olmsted’s partner in the design of Central Park, proposed a four-story, wide-windowed, thoughtfully designed set of “Parisian Buildings.” His drawing included an elegantly dressed couple entering the lobby, but that was wishful thinking. While the city’s population surged after the Civil War, and newcomers jammed into dank and rickety brick tenements, the affluent clung to increasingly exorbitant houses, even as they could hardly afford to build more of them. “Nothing denotes more greatly a nation’s advancement in civilization than the ornate and improved style of its architecture and the erection of private palatial residences,” the Times noted wistfully in 1869. With real-estate values spinning out of control, the editorial concluded that the only realistic way to beautify the city was to erect more mansions for sharing: “the house built on the French apartment plan.” If such a dubiously Continental innovation could be made to seem palatable, even splendid, to the upper crust, the bourgeoisie would surely follow. The first building to overcome these sensitivities was Richard Morris Hunt’s Stuyvesant Apartments at 142 East 18th Street, a luxurious behemoth by 1870 standards. This structure defeated doubters with a two-pronged argument of aesthetics and pragmatism. The architecture oozed dignity: Five stories high and four lots wide, it had an imposing mass, an overweening mansard roof with yawning dormers, wrought-iron balconies, and ornamental columns. Even more persuasively, compared with the cost of building, furnishing, cleaning, and repairing a private home, all this respectability came as a bargain. Within a few years, the Times announced that a “domiciliary revolution” had taken place: a happy epidemic of flats had beaten back a plague of sinister boardinghouses. Young couples could now afford a bright new place in town; families no longer needed to fan out to the villages that lay miles from Union Square. The change represented the triumph of pragmatism over prejudice. “Anglo Saxons,” the Times reported, “are instinctively opposed to living under the same roof with other people, and it is doubtful if [that resistance] would have been overcome had not the earliest flats been of an elegant kind, in the best quarters of the town, and therefore, expensive and fashionable.” The rich made the apartment safe for the middle class. Respectability was a crucial issue in a society as fluid as New York’s, where those who had achieved preeminence kept it only by erecting rigid social distinctions. In The House of Mirth, Wharton charts Lily’s decline by plotting her narrowing real-estate choices: She moves from a relative’s house to a spare, lonely apartment and then, after a brief stint as a social climber’s paid companion in a decadently luxurious hotel, she drifts even further downward to a shared one-room flat. She finally winds up in a boardinghouse, one step from the gutter. Next: The apartment building’s most persuasive asset. Sardine Life The Stuyvesant Apartments, 1870 (Photo: Berenice Abbott/Museum of the City of New York) Developers adopted an assortment of strategies to dispel qualms about apartments’ suitability. In 1884, the Chelsea opened as one of the city’s first luxury co-ops, sparing residents the indignity of living in hired quarters. (Having evolved from an owner-occupied enclave of the well-to-do into the storied and famously shabby Chelsea Hotel, it is now on the cusp of going condo; you can read about it here.) That same year, the Dakota offered crowd-shy burghers access to Central Park just outside their gate and, inside, a quiet courtyard enclosed by a mock château replete with peaked gables, bays, quoins, and wrought-iron railings. These lavish touches effectively collectivized social status: Whereas the one-family mansion declared its owner’s separate prominence, the Dakota’s bulk and ornamental façade signaled that everyone who lived there was, by definition, Our Sort. The apartment building’s most persuasive asset, though, was that it allowed the affluent to live better than ever while still downsizing the household staff. There were savings in numbers: In a large building, the cost of steam heat, electricity, and elevators could be shared. Instead of each family’s employing a laundress, one or two building employees manned huge machines in the basement. Residents of the finer addresses took their meals in vast and elegant central dining rooms, like passengers on a perpetual cruise. Those who preferred to eat at home but lacked a cook could have their cleverly boxed, lukewarm meals sent up by dumbwaiter. (New Yorkers always were addicted to takeout.) By the turn of the century, the mansion had become an albatross, not just expensive but primitive, compared with a giant technological wonderland like the Ansonia Hotel at Broadway and 74th Street, which opened in 1904. This was the bourgeois pleasure dome of early-twentiethcentury New York. The young single man who installed himself in one of the 1,400 rooms and 340 suites could choose whether to move in his own bed and chest or select from the hotel’s catalogue of paintings, furniture, carpets, and hand towels. He could scrutinize the other transient and permanent guests by the dazzle of electric lights, dine in a restaurant that served 550, take a postprandial stroll past the live seals cavorting in the lobby fountain, and ride the quiet, exposed elevators just for the pleasure of seeing the seventeen stories scroll by. A few blocks over, the Hotel des Artistes on Central Park West at 67th Street opened in 1917 as live-work space for gentleman artists, who required northern light and high ceilings, even though some residents never touched a palette. Jews, unwelcome on Fifth Avenue and in the other East Side redoubts of wealth, established Central Park West as their own opulent ghetto. There, the immigrant architect Emery Roth erected the apotheosis of early-twentieth-century domestic grandeur: the Beresford, a fairytale confection of towers, wrought-iron grillwork, terra-cotta cherubs, pediments, and balustrades. Each apartment pinwheeled around an entrance foyer, so that the sleeping quarters, public rooms, and servants’ wing could be simultaneously separate and close at hand. Only New York could produce a monument to Jewish home life as imposing as the Beresford, and perhaps only in the late twenties, in the exultant moment before the stock-market crash. The Depression slammed the portcullis down on the era of residential magnificence. The Ansonia was chopped up into cubbies. The Beresford was sold off for a pittance. The Majestic and the San Remo, planned in flush times, were completed in miserable ones and faced immediate financial trouble. Hundreds of other Upper West Side buildings, more modest but still genteel, adapted to less easeful times. Maids’ rooms were repurposed as bedrooms. Bell boxes for summoning servants were disconnected. Stained-glass windows broke and were replaced with ordinary panes. European refugees found in this habitat of battered prosperity echoes of the apartments they had left behind in Vienna and Berlin. Savage as it was, the Depression thinned but did not extinguish the ranks of the wealthy, and some sumptuousness did slip through the closing gates. In 1931, the River House materialized on East 52nd Street, and its 27-story tower, flanked by fifteen-story wings, rose over the East River like an ocean liner. Inserted into a neighborhood of slums and slaughterhouses, River House retreated behind its gated court, a citadel reaching far above the gloom. The luckiest residents never needed to dirty a shoe on the cobblestones: They could, if they wished, commute by boat to lower Manhattan or their Westchester estates from the private marina (an amenity later obliterated by the FDR Drive). The photographer Samuel Gottscho captured the thrill of living at these rarefied altitudes, when street level contained so much squalor. The haloed skyline, the chrome-plated water spreading out beyond the great bay windows, the airy apartments washed in morning light, all made River House the Valhalla of New York. Next: The arrival of rent control. Sardine Life In that first phase in the saga of the New York apartment, the middle class emulated the prosperous in order to separate themselves from the poor. In the next chapter, plain but modern housing for the poor became the standard for everyone else. Widespread hardship, followed by a world war and a housing shortage, plus a multi-decade campaign to flatten differences in income, meant that New Yorkers of all strata were moving into streamlined homes, with lower ceilings and restrained rents. Affordability and unassuming dignity had always been a goal of apartment advocates. In 1867, 1879, and 1901, Progressives had pushed through laws requiring small increases in the standards of ventilation, light, and sanitation in tenements, which were often disease-ridden firetraps. In the 1870s, the Brooklyn philanthropist Alfred Tredway White built handsome complexes of worker houses like the Tower Buildings in Cobble Hill, River House, 1931 which featured a toilet in each apartment, outdoor (Photo: Museum of the City of New York, Print staircases, meticulous brickwork, and wrought-iron Archives) railings. But it was the Depression that brought the issue of how to house the have-nots into the realm of public policy. In 1935, the New York City Housing Authority rehabilitated a neighborhood of crumbling Lower East Side tenements by tearing down every third house to maximize light and air, and renovating or rebuilding the rest. In the end, the First Houses project required near-total reconstruction, but the result inaugurated the public-housing era and remains an emblem of its promise. Providing apartments to those who needed them proved such a massive undertaking that all levels of government had to get involved. Rent control arrived in 1943, and a smorgasbord of federal, state, and city agencies floated bonds, granted tax breaks, wrote checks, evicted citizens, and redrew maps, all in an effort to scrub putrid slums and erect stands of thick, solid towers instead. Private developers, too, got in on the action. The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company opened Stuyvesant Town as a middle-class gated community around a series of verdant courts. One irony of that contradiction-laced period is that, in order to save the decaying city, densely populated towers cut themselves off from the noise and mess of urban life. This was not because residents wanted to distance themselves from the street but because planners did. “The growing antimetropolitanism of most housing architects [was] matched by the new suburban bias of the bankers, lawyers, and bureaucrats who wrote the programs and administered the policies,” write Robert A.M. Stern, Gregory Gilmartin, and Thomas Mellins in New York 1930. The story of mass housing is an intricate epic of idealism, destruction, and partial successes. Public projects obliterated neighborhoods, boosted the crime and segregation they hoped to alleviate, killed miles of street life, and vivisected vibrant communities—but they also redeemed a lot of grimly constricted lives. “Before, I lived in the jungle,” one garment worker said at the time. “Now I live in New York.” “I live in New York.” The optimism buzzing through that phrase brought people here in search of whatever damp, dim, cramped, and clanking digs they could find. Even as the authorities were condemning acres of cold-water walk-ups in East Harlem and the Lower East Side, Abstract Expressionist painters were renting similar apartments in Greenwich Village. If for Wharton’s Lily a poky flat represented the last rung before indigence and an early death, for the siblings in Ruth McKenney’s 1940 play My Sister Eileen (and its 1953 spinoff, Wonderful Town), a basement pad in the Village had a raffish, stageworthy glamour. Penury was cool. So powerful was the ideal of the apartment for the masses that luxury buildings aspired to it, too. Postwar architects embraced the austerities of modernism, which they applied to bourgeois quarters as rigorously as they did to public housing. The most bracing high-end apartment building was Manhattan House, an immense 1951 complex that architect Gordon Bunshaft clad in glazed brick that everyone called white, was actually pale gray, and has always looked slightly unwashed. Stretching along 66th Street between Second and Third Avenues, Manhattan House adapted the grand apartment to the stripped-down modern era persuasively enough to attract Grace Kelly as a resident, and Bunshaft chose to live there, too. But its huge scale, stark design, and chain of slabs sitting back from the sidewalk evoked Stuyvesant Town more than it did the ornate prewar palazzi like the Beresford. Half a century earlier, New Yorkers had hoped to live fabulously. Now it was stylish to live just well enough. It soon became difficult to distinguish Manhattan House from the knockoffs that developers churned out for less discerning clientele. For a while in the fifties and sixties, it seemed as though every new residential building, whether it contained cramped studios or assembly-line “luxury” pods, wore a uniform of glossy white brick. The postwar pathways of influence resembled the water cycle: an aesthetic of conspicuous sameness, developed for the poor and taken up by the affluent, trickled back to the middle. Next: How artists colonizing in Soho revived the entire city. Sardine Life The charms of standardization eventually wore thin, and the New York apartment soon experienced a transformation almost as fundamental as it had at the turn of the century. It began when the heirs to the coldwater bohemian culture of Greenwich Village drifted south across Houston Street and discovered a zone of gorgeous dereliction. In the sixties and seventies, the industries that had fueled the city’s growth a century earlier were withering, leaving acres of fallow real estate. At first, nobody was permitted to live in those abandoned factories, but the rents were low and the spaces vast, and artists were no more deterred by legal niceties than they were by graffiti, rodents, and flaking paint. They arrived with their drafting tables, their welding torches, movie cameras, and amplifiers. They scavenged furniture, blasted fumes and music into the night, and gloried in the absence of fussy neighbors. They would demarcate a bedroom by hanging an old 8 Spruce Street, 2011 sheet. (Photo: Adrian Gaut) At a time when urban populations everywhere were leaching to the suburbs, this artists’ colonization had a profound and invigorating effect not just on Soho but on the entire city. The traditional remedy for decay was demolition, but artists demanded the right to stay, their presence attracted art galleries, and a treasury of cast-iron buildings acquired a new purpose. Artists didn’t think of themselves as creating real-estate value, but they did. Few events illustrate the maxim “Be careful what you wish for” better than the Loft Law of 1982, which forced owners to make Soho’s industrial buildings fully habitable without charging the tenants for improvements. It was a triumph and a defeat. Legal clarity brought another wave of tenants, with more money and higher standards of comfort. As working artists drifted on to cheaper pastures in Long Island City, Williamsburg, and Bushwick, Soho’s post-pioneers renovated their lofts, hiring architects to reinterpret the neighborhood’s industrial rawness, or merge it with cool pop minimalism, or carve the ballroom-size spaces into simulacra of uptown apartments. Once everyone wanted to be a tycoon, then everyone wanted to be middle-class. Now everyone wanted to be an artist, or live like one. Soho filled up quickly, and the idea of the loft spread, reinterpreted as a marketable token of the unconventional life, promising to lift the curse of the bourgeoisie through the powers of renovation. Realtors began pointing out partition walls that could easily be torn out. Lawyers, dentists, and academics eliminated hallways and dining rooms, folding them into unified, flowing spaces. Happily for those with mixed feelings about the counterculture, loftlike expansiveness overlapped with the open-plan aesthetic of new suburban houses. Whether in imitation of Soho or Scarsdale, the apartment kitchen migrated from the servants’ area to the center of the household, shed its confining walls, and put on display its arsenal of appliances and the rituals of food preparation (not to mention the pileup of dirty crockery). Cooking became a social performance, one that in practice many apartment dwellers routinely skipped in favor of ordering in, going out, or defrosting a package—but at least the theater stood ready. Starting in the eighties, when the country more or less abandoned the pursuit of greater equality and success was defined by fresh college graduates who coaxed the financial system into dumping sudden millions in their laps, the apartment took yet another turn. Triumphant traders—“Masters of the Universe,” in Tom Wolfe’s phrase—didn’t spend much time at home, but in their few moments of leisure they wanted to gaze down on the city they had conquered. The ultimate trophy was an imperial view. For the next two decades, developers treated the apartment less as a private retreat than as a belvedere—a platform for a vista. Clunky towers with floor-to-ceiling windows sprouted around the city, their hurried construction, slapdash design, and astronomical prices justified by the assumption that anyone who walked through the front door would make straight for the windows. The city became a diorama of itself. The ultimate expressions of the panoramic apartment, which required vertiginous height, very fast elevators, and a perimeter of glass, are the penthouses atop Trump World Tower. This dark bronze totem that Costas Kondylis designed on First Avenue for Donald Trump was the planet’s tallest residential building (and the one most loathed by its neighbors) when it opened in 2001, and it was not shy about its stature. The ceilings got higher near the top, so that the tower appeared to be craning its neck, and the 72 floors were deceptively numbered up to 90. The payoff was an Imax view of the skyline below and the weird sensation that the closest neighbors were gulls, planes, and clouds. Of course, that sort of solitude only lasts until the next set of neighbors climbs the beanstalk. Already, Frank Gehry’s 867-foot rental tower at 8 Spruce Street has nudged past Trump World Tower, and the hotel-condominium designed by Christian de Portzamparc and currently under construction at 57th Street and Seventh Avenue will shoot above them both to 1,005 feet. The push to refine the apartment began with assurances that a fifteenth-floor home could rival a house set on a fifteen-foot stoop; today, a 150th-floor penthouse is not unthinkable. Next: What we really choose when we choose an apartment. Sardine Life Vertical living has behaved as promised: It multiplied the value of limited land, streamlined the machinery of leisure, sheltered the masses, and concentrated entrepreneurial energy into a compact urban zone. But the price of height is lightweight construction: glass walls, thin floors, and plasterboard walls. The original barons of the Beresford would have found today’s condo towers pretty flimsy castles in the sky. And yet New York has done such a thorough job of glamorizing the high-rise apartment that a Manhattan pied-en-l’air has become a billionaire’s accessory and an eternal object of desire. Developers have searched for ways to leverage that lust—to reconcile the assembly-line efficiencies of the construction business with the quest for ever-greater heights of pampering. Enter the preposterous amenity. Today, the most extreme buildings compete to provide a Gilded Age menu of extras: swimming pools, gyms, spas, garages, valet parking, concierge service, room service, housekeeping service, wireless service, rooftop dog runs, party rooms, screening rooms, and so on. You can never be too rich or too comfortable. In theory, the ultrahigh-rise should not be simply an instrument of extravagant living but a path back to the egalitarian policies of the mid–twentieth century. In his recent book Triumph of the City, the Harvard professor Edward Glaeser argues that New York’s vitality depends on people being able to live here, that the only way to make apartments affordable is to erect more of them, and that means rising higher and higher. If he’s right, then perhaps all the contradictory forces of New York’s real-estate history can somehow be intertwined, and the next generation of apartment buildings can somehow combine affordability with vintage grandeur, great height, and the relentless pursuit of ease. That may seem like an implausible quartet of attributes, but it’s precisely what the first middle-class alternatives to the tenement and the boardinghouse offered 150 years ago. Almost the entire trajectory of the New York apartment remains on the menu today. To choose an apartment here is to select one particular vision of what New York life can be. The crowds who troop around to open houses every Sunday are never just counting bathrooms and closets or calculating mortgage payments. They’re wondering whether they want to join the centennial parade of families who have occupied this particular enclosure, whether a refurbished tenement speaks of hoary miseries or new excitement, whether the view out each window is one they want to see every day, or whether they can see themselves in their prospective neighbors. To hunt for an apartment is to decide which New York you belong in, and what specific droplet of the city’s fickle soul has found its way into your veins. NY Chapter AEE Board Members David Ahrens Michael Bobker Robert Berninger dahrens@energyspec.com mbobker@aol.com rberninger1@verizon.net 718- 677-9077x110 646-660-6977 212- 639-6614 Jack Davidoff Fredric Goldner Bill Hillis Dick Koral John Leffler Robert Meier Ryan Merkin Jeremy Metz John Nettleton Asit Patel Dave Westman jack@energyconsultingservices.com 718-963-2556 fgoldner@emra.com 516- 481-1455 wjhjr.1@juno.com 845-278-5062 dkoral@earthlink.net 718- 834-1626 johndelnyc2@juno.com 212-868-4660x218 rmeier@lime-energy.com 212-328-3360 rmerkin@hotmail.com 212-564-5800 x 16 jeremy.metz@verizon.com 212-338-6405 jsn10@cornell.edu 973-762-8560 apatel@aeanyc.org 718- 292-6733x205 westmand@coned.com 212-460-6588 Board Members Emeritus Paul Rivet energyx@verizon.net George Kritzler gkritzler@aol.com Alfred Greenberg agpecem@verizon.net George Birman (RIP) Timothy Daniels twdaniels44@hotmail.com Chris Young c-young1@att.net 914-422-4387 212- 312-3770 914-442- 4387 Past Presidents Placido Impollonia (2007-09), John Nettleton (2005-07), Mike Bobker (2003-05), Asit Patel (2000-03), Thomas Matonti (1998-99), Jack Davidoff (1997-98), Fred Goldner (1993-96), Peter Kraljic (1991-92), George Kritzler (1989-90), Alfred Greenberg (1982-89), Murray Gross (198182), Herbert Kunstadt (1980-81), Sheldon Liebowitz (1978-80), FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, economic, scientific, and technical issues. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.