For 19th and 20th English and American Satire

advertisement

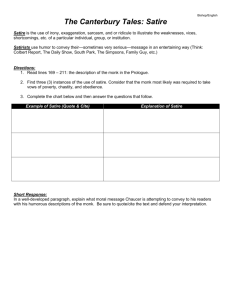

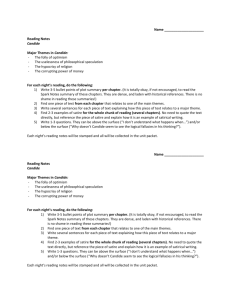

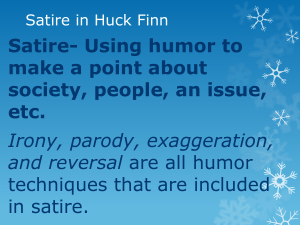

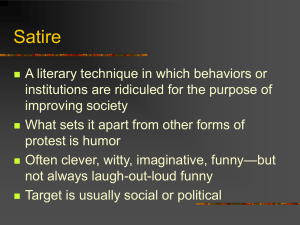

Daniel J. Bauer – English Department For Masterpieces of World Literature Two of the important opening pieces of literature we will study in this course are fine examples of literary satire. They are Moliere’s 17th century drama Tartuffe, and Voltaire’s novella of epic value in the history of literature, Candide. When readers begin to tackle literary satire, they need to be aware of the special characteristics of this very intriguing literary genre. “Genre” of course refers to “type of literature.” The very word “genre” has much to do with the essence of literary satire. In literature we speak of various kinds of genre, such as poetry, essay, short story, comedy, tragedy, novel, and so on. Satire is a genre that is essentially a form of social criticism. Satire attacks weaknesses in human nature, in individual persons, or in institutions. The attack of satire in theory has as its motivation the intention to encourage positive change, or what we often term “reform.” Weaknesses in human nature which satire might well attack include almost any human weakness or failing. In Voltaire’s great satirical work Candide, the author attacks Candide as a character for being too trusting of authority figures, particularly of Pangloss his professor / master. As a disciple or student of Pangloss, Candide ought to become far more critical, more independent in thinking than he seems to be for almost all of the text. Pangloss mouths bits and pieces of scientific and philosophical theories popular in the 18th century, but does not grasp the important gap between those ideas and the world of harsh, practical reality. The so called teacher functions as a type of parrot, repeating phrases about cause and effect, this world being the best of all possible worlds and so on, but in so doing consistently turns a blind eye to chaos, confusion, and various forms of human suffering all around him. Among the institutions that Voltaire attacks in the text Candide are the Catholic Church he knew in the 18th century, science, medicine, education, militarism, and the very making of art and literature itself. We need to see that satire in one way or the other almost always uses techniques - tools we could say - - such as juxtaposition, repetition, parody (the imitation of known forms or traditional, ritual formulas of ideas and practices), exaggeration, and grotesquery. Satire must offer to readers an opportunity to laugh, to find humor in human folly. If laughter and some type of comic response is not present in a text, what we have is perhaps diatribe or accusatory literary, propaganda perhaps, but not genuine satire. Characters in works of satire typically function more or less like machines. Various qualities about the characters are similar to wheels and cogs and levers in an engine. Push a button or pull a certain rope, and the character may will kick into motion as if “it” is battery-powered. Touch anything on the topic of “the world,” and suddenly Pangloss in Candide begins assuring readers that this is “the best of all possible worlds.” Allow Candide as a character to observe some horrible effect in his society or environment and he will automatically ask “What is the cause of this?” A character uses the word “love,” and Candide begins to sing the praises of his love, Cunnegunde. This mechanical type response of many characters in satire is all by design, of course. Authors use such characters to teach lessons to readers, and often the lessons are negative ones: Do not imitate this character by attitude or conduct, may be the lesson. In addition to offering a caveat, a warning not to be like this in our personal lives, such characterizations often strike readers as deeply humorous or somehow comical. Jim Smiley in Mark Twain’s great “The Notorious Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” is an extremely comical figure partly because he is so automatic, so machine-like in his desire to gamble. The character Orgon in Moliere’s great Tartuffe is similarly humorous for readers because of his inability to think rationally and to only respond to those around him through the lens of his bias, his stubbornness, his ridiculous efforts to impose his authority on others. Again, the machine-like (knee jerk) reactions of these types of characters are all part both of the attack and the comic effect the authors are hoping to make. Never invest emotion and identify personally with characters in a work of satire. These characters may have some realistic features and may remind us of persons we actually know in our historical (personal) lives, but they are essentially made of cardboard and thus to one degree or the other are shallow, unreliable characters. Realism does exist in some ways of course in satire as a literary genre, but that is a complex Q in itself, and one that deserves a more thorough discussion than I am able to offer here.