GM Cries Foul

Over New Twist

In Coupon Plan

By Richard B. Schmitt

07/16/1999

The Wall Street Journal

Page B1

(Copyright (c) 1999, Dow Jones & Company, Inc.)

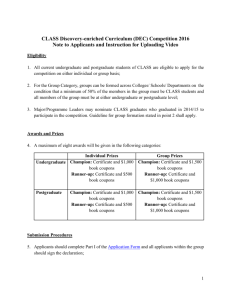

When General Motors Corp. settled a protracted lawsuit over millions of allegedly

defective pickup trucks in January, it was good for GM but not necessarily good for

the trucks' owners.

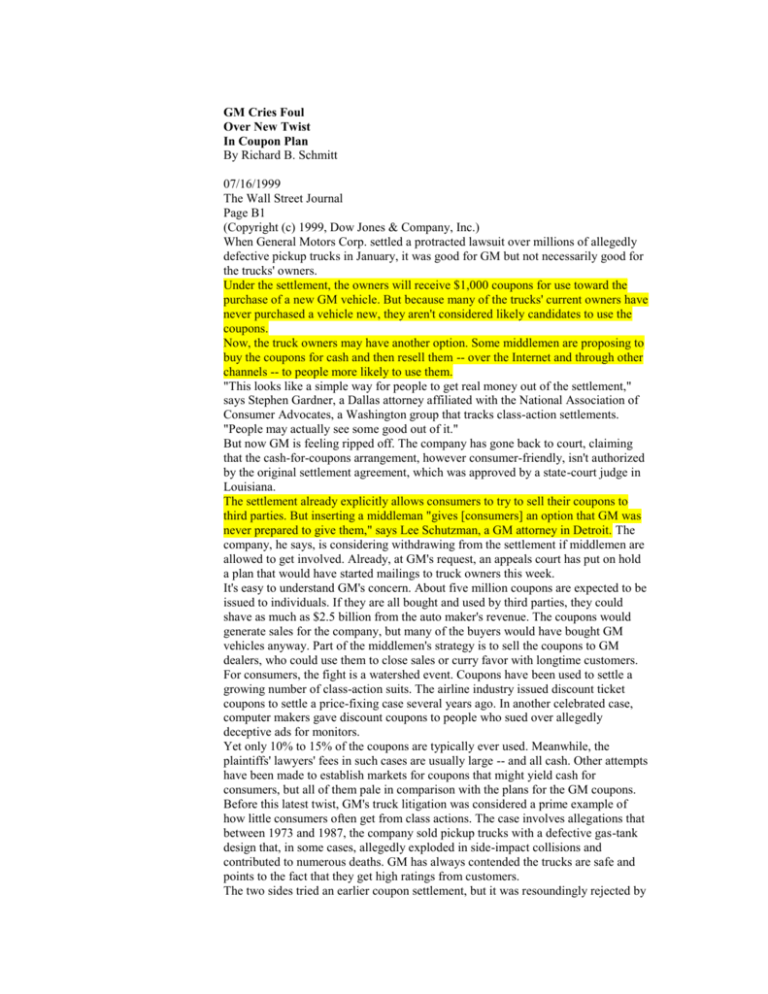

Under the settlement, the owners will receive $1,000 coupons for use toward the

purchase of a new GM vehicle. But because many of the trucks' current owners have

never purchased a vehicle new, they aren't considered likely candidates to use the

coupons.

Now, the truck owners may have another option. Some middlemen are proposing to

buy the coupons for cash and then resell them -- over the Internet and through other

channels -- to people more likely to use them.

"This looks like a simple way for people to get real money out of the settlement,"

says Stephen Gardner, a Dallas attorney affiliated with the National Association of

Consumer Advocates, a Washington group that tracks class-action settlements.

"People may actually see some good out of it."

But now GM is feeling ripped off. The company has gone back to court, claiming

that the cash-for-coupons arrangement, however consumer-friendly, isn't authorized

by the original settlement agreement, which was approved by a state-court judge in

Louisiana.

The settlement already explicitly allows consumers to try to sell their coupons to

third parties. But inserting a middleman "gives [consumers] an option that GM was

never prepared to give them," says Lee Schutzman, a GM attorney in Detroit. The

company, he says, is considering withdrawing from the settlement if middlemen are

allowed to get involved. Already, at GM's request, an appeals court has put on hold

a plan that would have started mailings to truck owners this week.

It's easy to understand GM's concern. About five million coupons are expected to be

issued to individuals. If they are all bought and used by third parties, they could

shave as much as $2.5 billion from the auto maker's revenue. The coupons would

generate sales for the company, but many of the buyers would have bought GM

vehicles anyway. Part of the middlemen's strategy is to sell the coupons to GM

dealers, who could use them to close sales or curry favor with longtime customers.

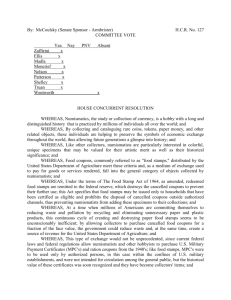

For consumers, the fight is a watershed event. Coupons have been used to settle a

growing number of class-action suits. The airline industry issued discount ticket

coupons to settle a price-fixing case several years ago. In another celebrated case,

computer makers gave discount coupons to people who sued over allegedly

deceptive ads for monitors.

Yet only 10% to 15% of the coupons are typically ever used. Meanwhile, the

plaintiffs' lawyers' fees in such cases are usually large -- and all cash. Other attempts

have been made to establish markets for coupons that might yield cash for

consumers, but all of them pale in comparison with the plans for the GM coupons.

Before this latest twist, GM's truck litigation was considered a prime example of

how little consumers often get from class actions. The case involves allegations that

between 1973 and 1987, the company sold pickup trucks with a defective gas-tank

design that, in some cases, allegedly exploded in side-impact collisions and

contributed to numerous deaths. GM has always contended the trucks are safe and

points to the fact that they get high ratings from customers.

The two sides tried an earlier coupon settlement, but it was resoundingly rejected by

a federal appeals court in Philadelphia. The court deemed the agreement a marketing

coup for GM and a boondoggle for plaintiffs' lawyers. Ultimately, the suit was

settled and approved by a state court in rural Plaquemine, La., after GM's Mr.

Schutzman began negotiating with plaintiffs' lawyer Michael Crow.

While the settlement allows the coupons to be sold to third parties, their value would

decline to $500 after such a sale. Mr. Schutzman says GM agreed to that provision

so that truck owners could "advertise in the paper" or attempt to sell their coupons

outside a dealership. When Mr. Crow's team unveiled the ambitious trading plan in

May, GM was furious.

Mr. Crow argues that the "secondary market" is consistent with the settlement's

objective of allowing holders to sell the coupons for cash, and that GM is opposed

merely because it is afraid of losing a lot of money. "GM woke up and said, `We

think you did too good a job,'" he says, adding that without the market-oriented

feature "it is a lousy settlement."

Under the plan, a newly formed, closely held company known as the Certificate

Redemption Group would offer to buy any and all of the coupons from truck owners

for $100 each, which amounts to 20% of their value to the final purchaser. Mr. Crow

says the lawyers conducted focus groups that indicated most truck owners would

rather get a quick check than go through the hassle of selling the coupons

themselves.

"I could use the hundred dollars," says Joseph Foto, a Kenner, La., security guard

and 1981 GMC truck owner. With three kids, he says, he isn't in any position to buy

a new vehicle anytime soon anyway.

The lawyers got approval from the Louisiana court overseeing the settlement to

enclose the purchase offer when information about the coupons is mailed to truck

owners.

James Dawley, CRG's chief executive, says he's already lining up potential buyers

for the coupons, including banks, leasing companies and GM dealers. He says he

can't tell yet how much the coupons will fetch, but he hopes to sell them for $150 to

$200 apiece. He adds that some other major auto makers have expressed interest in

honoring the coupons, seeing them as a possible way to capture GM customers.

"GM has an opportunity to make a public-relations coup. They've fought the good

fight. They should sit down and find a way to work with their customers," says Mr.

Dawley, a Houston entrepreneur who made a fortune selling insurance to oil

companies in the 1980s. He was in retirement when plaintiffs' lawyers approached

him about getting involved in the GM case.

GM responds that boosters of the plan are attempting to rewrite history. In court

papers, the company says the plans were never specifically agreed to and

"drastically change the character of the settlement."

Mr. Dawley is guaranteeing the $100 only for the first 30 days of the settlement.

After that, if he has trouble reselling the coupons, he can reduce the offering price.

Mr. Crow and other plaintiffs" lawyers in the case, who are earning $24 million in

fees from the settlement, have their own interest in the market. As part of a side deal

to win the backing of consumer groups, the lawyers agreed to put $10 million of

their fees in escrow until 100,000 of the coupons were sold for $100 each. If fewer

coupons are sold, the lawyers will have to make up the difference.

Last month, Jack Marionneaux, a state-court judge in Plaquemine, rejected a GM

bid to shut down the market before it opened. "The court finds nothing collusive or

inappropriate with class counsel's attempt to facilitate the efficient operation of a

secondary market," he wrote. He also said that rules about the coupon program that

GM was sending to its dealers were in some cases "incorrect" and that the company

seemed to be taking its view of the settlement agreement "for no other reason than to

frustrate the operation of a secondary market." GM has appealed.

Copyright © 1999 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.