Job Design Overview

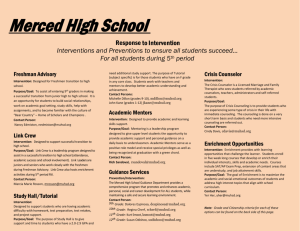

advertisement

JOB DESIGN Overview Most reported correlational and experimental studies in the area of Job Design support the conclusion that jobs which offer variety, and require the individual to exercise discretion over his work activities, lead to enhanced well-being and mental health. Furthermore, the evidence shows how even extremely routine, machine paced jobs can be re-designed to include greater variety and responsibility. Such changes are sometimes accompanied by economic benefits to the firm (through reduced labour turnover, for instance), although the smaller claim, that in simple economic terms the company is not worse off, may be more often correct. Many large and prosperous organisations have developed their own approaches to job design with such persistence that we must infer that in practical terms they have recognised its value to them and to their employees. Job Design procedures cannot serve as a universal medicine to cure any organisational illness. It is apparent for example that some jobs cannot readily be changed to increase operator well-being, perhaps because of technological constraints or because the working conditions are inalterably awful. Job-design principles of a different kind may here be more appropriate - elimination of the employee's task through automation, for instance. The fact that payment changes will be required to most job-design exercises should also be stressed. Job enrichment requires an individual to take over additional responsibility; the discretionary element of his work is being increased relative to its prescribed content. Additional discretion is usually seen to merit an increase in pay. The obverse of this fact presents difficulties for attempts to operate an enrichment programme in a piecework department; in order to introduce piecework in the first place, much of the employee's potential discretion had to be taken away from him, and it cannot now easily be restored. For this reason many of the more successful job-design schemes have tended to incorporate some form of performance related pay. Just as there are differences between jobs in their potential for enrichment, so are there major variations between people. There is little doubt that many manual workers take a largely instrumental view of their work, valuing it primarily in terms of its financial return and assessing possible improvements mainly in cash terms; the phrase `job enrichment' may have a hollow ring to them. Others are stretched by the requirements of their work as it is, and cannot easily face an additional load, while some are simply unwilling to consider seriously any alterations to a system with which they have become comfortably familiar. We should however draw attention to the fallacy of accepting people's initial responses to such proposals as the last word in the matter. Job re-design involves a continuing process of learning and opinion change. Several reports of altered work systems have stressed how employees influence developments, so that they may gradually come to terms with quite considerable changes in their jobs. Den Hertog (1976) summarises a study in Philips as follows: "One of the most important things is that work-structuring itself is a learning process in which people learn to control their own work situation, to see the way". He notes how people's expectations and values alter in these learning situations. One group of married women employees had been loath to change from their repetitive jobs, but after a year of autonomous group-working they found it difficult to understand how they could have been satisfied with their previous arrangements. Such a change of aspiration level is regularly observed by practitioners in this field. One practical feature which can affect the appropriateness of attempts to redesign jobs is the breadth of variation within the group which is performing a job. If the people involved range in age from their teens to their sixties and are of widely differing intelligence, then they are unlikely to be uniformly able to accept a programme of enrichment. This suggests that varying workmethods will ultimately be required within the prescribed set of tasks whereas others producing the same item will prefer greater discretion. The attitudes of the trade unions involved are additional factors influencing the likely success of job-design attempts. It is clear that many shop stewards and full-time union officials have reservations about the philosophy behind the approach. They see that in some respects workers are being asked to take over managerial functions, a step which could threaten the traditional union role. Within parts of the engineering, mining and other industries there is still a strong feeling that working-indirect encroachments by management. In so far as the acceptance of job design by subordinates presupposes their willingness to become in some respects their own managers, there exists a clear conflict of roles for many trade unionists. Finally, the industrial relations climate with an organisation crucially determines the outcome of attempts to re-design jobs. In a sense this point subsumes all the others: if the atmosphere has traditionally been one of usversus-them, where every move by management is viewed with deep suspicion among the workforce and where managers have little respect for their subordinates, proposals for job re-design are unlikely to get off the ground. This does not mean, however, that both management and unions should not set them up as objectives to be attained after sometime: they may first work together to minimise job dissatisfaction and later cooperate on the more positive aspects of well-being.