Thank you for downloading this assignment

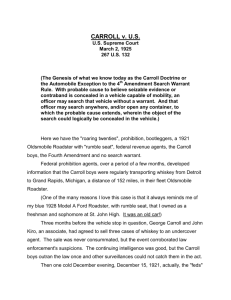

advertisement

ENVIRONMENTAL & ENERGY LAW & POLICY JOURNAL APPLICATION EXAMINATION Dear Applicant: Thank you for downloading this application. You are one step closer to becoming a member of the Journal. Please (1) fill out the application, (2) complete the cite check exam, and (3) paste both your resume and writing sample below. The writing sample may be either of last year’s LRW assignments or a separate paper that you feel best demonstrates your writing and citation ability. The writing sample is in addition to the 500 words on why you want to join EELPJ. Applications will be accepted from June 1 through June 11 at 11:59PM. Late applications will not be accepted. Applications will be reviewed on a rolling basis. The Journal will notify all applicants by June 16 of acceptance or if the write-on process will be necessary for membership. Anyone not accepted through the application process is strongly encouraged to compete in the write-on competition. SUBMISSION: After completing the application and exam, please send your final document to eelpj@uh.edu. Name your document LastnameFirstname.doc (example: WeinerRussell.doc). TURN ON TRACK CHANGES. LOCATED UNDER THE TOOLS MENU Name: Section: Fall LRW Grade: Spring LRW Grade: G.P.A.: Class Rank: Max 500 words why you want to join the Environmental & Energy Law & Policy Journal: I. The Exam The following assignment is designed to test some of the skills required from members of EELPJ. The exam is intended to simulate the submission of a legally sound but lazily checked paper. The cite check exam is a four page excerpt taken from an unpublished but well written paper. We deliberately introduced a large number of errors. Such errors include but are not limited to: Spelling Grammar Formatting Citations (wrong pages, wrong dates, formatting) Citations that do not support the proposition stated Signals Repetition Legalese Redundancy Plagiarism II. Citations You should check all cited sources in addition to grammar and style. It may not be necessary to read every single case. It may be sufficient to look up the pinpoint cite or read the brief and headnotes. Other times, it may be necessary to read the case for accuracy of the author’s proposition. Remember that citations must be corrected to Bluebook (18th Edition) Law Review standards. We will compare your corrections to the original document, but obviously, some corrections will be a matter of style and will be judged accordingly. Your version should NOT be longer than the original. III. Duration of Exam Please do not spend too long on this assignment. We feel that five hours should be more than sufficient and reflects the expected productivity of those working on the Journal. IV. Making Changes to the Excerpt Enter your changes into the excerpt below using Microsoft Word. Please be sure to turn on track changes under the tools menu. This will allow us to see what changes you have made to the document. Once you make all of the changes, paste your resume and writing sample in the space provided below. V. Applicant Questions If you have any questions regarding these instructions, please contact Ronnie Durham, Editor-in-Chief, at rdurham@central.uh.edu or Jennifer Hopgood, Chief Articles Editor, at jlhopgoo@central.uh.edu. We will try to answer you promptly, but we cannot answer questions about issues being tested. Thank you for considering EELPJ. We look forward to working with you in the future. Good Luck. [Paste your resume here] [Paste your writing sample here] Court decisions related to automobile searches and seizures a. Fourth Amendment Rights It is without doubt that the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution promises the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, “and no warrant shall issue, without probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.”1 This language might stand for the preposition that for searches by government officials to be reasonable, they must have a warrant issued, and that warrant must be on the basis of probable cause.2 But, the language, in practice has been interpreted to allow warrantless searches in a number of circumstances. 3 Exceptions to the general requirement of a warrant include when consent has been given,4 when exigent circumstances exist,5 when evidence is in plain view of the enforcement authorities,6 when the suspect is the subject of a “Terry” stop7 and when the search is done and performed at the time of the arrest.8 Another exception applies in cases involving automobiles9, which I discuss below. 1 US CONST. amend. IV. Probable cause for the issuance of a search warrant is defined as facts or apparent facts as viewed through the eyes of an experienced police officer which would lead a man of reasonable caution to believe that there is something connected with a violation of law on the premises to be searched. J. SHANE CREAMER, The Law of Arrest, Search and Seizure 11 (1975). 3 See N. GARY HOLTEN & LAWSON L. LAMAR, THE CRIMINAL COURTS: STRUCTURES, PERSONNEL, AND PROCESSES 151-153 (1991). 4 See Schneckloth v. Bustamonte, 312 U.S. 218, 228 (1973). 5 See Minnesota v. Olson, 495 U.S. 91 (1990) 6 See Horton v California, 469 U.S. 28 (1990). 7 See Terry v. Texas, 392 U.S. 1 (1968). 8 See Chimel v California, 395 U.S. 752 (1969) & New York v. Belton, 453 U.S. 454 (1981). 9 See Carroll v. United States, 267 U.S. 132 (1942). 2 It may be surprising to some, but there are certain types of searches and seizures that are analyzed completely outside the context of probable cause altogether. For example, police officers may automatically conducts an inventory search of items left in their care and custody.10 Similarly, law enforcement and customs agents are given broad discretion to conduct searches and seizures at foreign borders11. Some check-points and road-blocks are also good in the absence of a probable cause.12 These types of governmental intrusions are justified not by the existance of a warrant or probable cause, but rather as an administrative or community caretaking necessity. To some extent, 4th Amendment jurisprudence can be categorized by the case law that has developed from each of the exceptions to the general warrant requirement and the various types of admin and regulatory searches and seizures. Each of these areas are governed by special rules when the search or seizure is done on an automobile. However, the Court relied on a set of common rationales in each of these areas and principles in deciding all search and seizure cases that are connected to autos. These guilding standards were first articulated and developed in the the automobile search warrant exception cases, and stand as guidelines for the courts. b. The Carroll Doctrine The car exception of the requirement of a warrant was initialy a response to vehicle mobility.13 When faced with situations involving suspected criminals and / or evidence in 10 See South Dakota v. Opperman, 428 U.S. 364 (1976). See Michigan Dept of State Police v. Sitz, 496 U.S. 44, 450 (1990). 12 United States v. Martinez Fuerte 428 US 543 (1976) 13 Kevin Corr, A LAW ENFORCEMENT PRIMER ON VEHICLE SEARCHES, 30 Loyola University Of Chicago Law Journal 1, 16 (1998). 11 an automobile14 that could be easily moved out of a policeman’s jurisdiction. It could also be moved simply to another location where it might no be found again, the Court has odopted allowing the police to search absent a warrant. This exception applies in those cases where probable cause exists in believing that evidence of a crime will be found if a vehicle search is conducted. Thus the two main ingredients to the exception are bona fide probable cause and immediate exigency. The foundating decision for the aformentioned automobile exception is Carroll v United States.15 This Carroll case involved the warrant-less search of an car believed to be carrying bootleg alcohol during the the 1920s, when it was the Prohibition Era are alcohol was illegal.The expected bootleg brew, upon searching the car, was found and seized.16 The defendant, of course, later challenged the search and the admission of the liquor into evidence.17 In its decision, The Supreme Court took time to analyze earlier cases and the Farmers desires in drafting the Fourth Amendment language.18 In clear and unmistakable language, the court stated that in deconstructing the Fourth Amendment vehicles are I use the terms “automobile,” “car,” and “vehicle” interchangeably without any indented difference in definition. Fourth Amendment case law in this area seems to apply to all motorized vehicles, including air and watercraft and motor homes. See California v. Carney, 471 U.S. 386, 393 n.2 (1985). 15 Carroll v. United States, 267 U.S. 132 (1925) 16 Federal prohibition agents were on a regular tour of duty patrolling the highway between Detroit and Grand Rapids, looking for violators of the Prohibition Act, when they spotted a car driven by George Carroll and John Kiro, two suspected bootleggers. The agents stopped the vehicle and conducted a warrantless search on the belief that the car contained bootleg liquor hidden inside the seat. The police found that the upholstery seat filling had been removed, and discovered a substantial amount of liquor. Carroll and Kiro were convicted of transporting “intoxicating spirituous liquor.” 17 Catherine A. Shepard, Search and Seizure: From Carroll to Ross, the Odyssey of the Automobile Exception, 32 Cath. U. L. Rev. 221, p225 (1982). 18 Carroll, 267 U.S. 132, [get page #s for this]. 14 treated differently than dwellings and other like structures.19 The court’s justification for this difference was really high mobility of the vehicle.20 Mobility was clearly a factor in Mr. Carroll’s case because the car was initially observed on the highway and then stopped on the highway.21 In a large number of cases, Carroll has since been followed, applied, and approvingly cited many times22, and almost never criticized or distinguished. Id. at 151. (where the Court stated that “the guaranty of freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures by the Fourth Amendment has been construed, practically since the beginning of the government, as recognizing a necessary difference between a search of a store, dwelling house, or other structure in respect of which a proper official warrant readily may be obtained and a search of a ship, motor boat, wagon, or automobile for contraband goods, where it is not practicable to secure a warrant, because the vehicle can be quickly moved out of the locality or jurisdiction in which the warrant must be sought.”) 20 Id. 21 Id. 160. 22 See Chambers v Maroney, 399 U.S. 42, 49-50 (1970) (amusingly listing some of the cases that have followed in the “tyre tracks” of Carroll). 19