WARRANTLESS SEARCHES OF AUTOMOBILES Paul Stuckle

advertisement

WARRANTLESS SEARCHES OF AUTOMOBILES

Supreme Court Decisions From Carroll to Ross

'

f

Paul Stuckle

Independent Research

1st Summer Session, 1982

Professor Larkin

••• By either course we might bring some

modicum of certainty to Fourth Amendment

law and give the law enforcement officers

some slight guidance in how they are to

conduct themselves.

Justice White,

dissenting in Coolidge v. New Hampshire

00 ,~~ .')

--~V

PART ONE:

PROBABLY CAUSE TO SEARCH

It has been said frequently, and with surprising accuracy, that

history repeats itself. For legal scholars, nowhere is the lesson of

history more applicable than in the constitutional law of warrantless

searches of automobiles. After approximately sixty years of litigation,

beginning in 1925, the Supreme Court's holding in the 1982 case of the

United States v. Ross, 1 ends up basically where it all began. Without needlessly attempting to tarnish the infinite wisdom of the Court, as this was

an admittedly "troubled area, .. those sixty year_s were filled with more curves,

yellow flags, and incredible finishes than the Indianapolis 500. For in

the law of automobile searches, the United States Supreme Court took us all

on a ride.

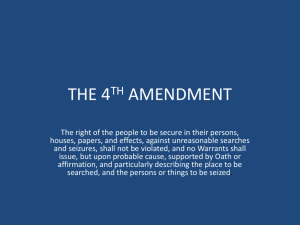

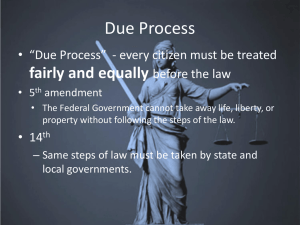

Searches and seizures are governed by the Fourth Amendment to the

Constitution which is applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Fourth Amendment states:

~

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses,

papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures,

shall not be violated and no warrants shall issue, but upon

probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly

describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things

to be seized.2

Even though the Fourth Amendment does not specifically mention automobiles,

there is no question that vehicles are entitled to protection under the

Amendment. As the Court said in United States v. Chadwick, 3 "automobiles

are 'effects• under the Fourth Amendment, and searches and seizures of

automobiles are therefore subject to the Constitutional standard of reasonableness."4

The crucial issue in all search and seizure cases is whether the

Fourth Amendment's requirements have been complied with. If not the exclusionary rule, i.e., any evidence obtained illegally will not be admissible

in court, takes effect. The exclusionary rule for federal prosecutions was

5

established by the Supreme Court in 1914 in Weeks v. United States.

It

was applied to state prosecutions in the 1961 Supreme Court decision of

Mapp v. Ohio. 6 The underlying rationale of the exclusionary rule was

7

explained by the Court in Walder v. United States:

The Government cannot violate the Fourth Amendment--in the only

way in which the Government can do anything, namely through its

',.

I

•

2

agents--and use the fruits of such unlawful conduct to secure a

conviction . . . Nor can the Government make indirect use of such

evid:nce for its case, ••. or support a conviction on evidence

obta1ned through leads from the unlawfully obtained evidence, . . .

All these methods are outlawed, and convictions obtained by means

of ~hem are i~validated, because they gncourage the kind of

soc1ety that 1s obnoxious to free men.

With these rudimentary Fourth Amendment principles in mind, this paper

shall take an inqepth look at the constitutional law of warrantless searches

and seizures of automobiles. The primary issues to be discussed include:

the scope of vehicle searches; the requisite of pr~babl~ cause to search;

time constraints on searches; and the troubled area concerning containers

and automobile compartments. The paper will not cover two other doctrines

connected with automobile searches: search incident to arrest and inventory

searches. A search incident to arrest occurs when a police officer lawfully

arrests the occupant of a vehicle, he may then search the area that is within

the occupant•s immediate control. An inventory search problem takes place

/when there is not probable cause to search the vehicle after it has-oeen

seized. Rather, this paper is concerned primarily with warrantless probable

cause automobile searches. We begin back in the 1920s, as prohibition

created a huge black market for the transportation of illegal alcohol, and

the courts were first faced with the constitutional law problem of searches

involving automobiles.

In 1925, the United States Supreme Court decided the case of Carroll

v. United States. 9 The defendant, Carroll, was convicted for transporting

intoxicating liquor in an automobile in violation of the National Prohibition

Act. Carroll argued to have the conviction set aside on the grounds that

the search and subsequent seizure of his vehicle violated the Fourth Amendment, and therefore that the use of liquor as evidence was impermissible

under the exclusionary rule. The facts in Carroll showed federal prohibition

agents patrolling a known .. bootlegging .. highway between Grand Rapids and

_,

Detroit when they spotted the defendant's vehicle. The defendants were

known by the agents 'to engage in the illegal transportation of liquor.

The agents stopped the defendants and searched their car. Upon ripping out

the upholstery of the seats, the agents found sixty-eight bottles of the

illegal contraband. The officers were not anticipating that the defendants

would be driving on the highway at that particular time, but upon spotting

them the officers believed the defendants were carrying liquor, and soon

followed the search, seizure, and arrest.

\

3

Mr. Chief Justice Taft delivered the majority op1n1on of the Court.

The opinion first delineated sections of the National Prohibition Act,

which granted law officers the authority to seize contraband when they

discovered any person in the act of transporting liquor. However, a

supplemental act which had passed through the Senate, the "Stanley Amendment," prescribed stiff penalties for officers who made a warrantless search

of any property. A committee from the House of Representatives advocated

strongly against the proposed Amendment:

Not only does this Amendment prohibit search of any lands, but it

prohibits the search of all property ••• But what is perhaps more

serious, it will make it impossible to stop the rum-running automobiles engaged in like illegal traffic. It would take from the

officers the power that they absolutely must have to be of any

service, for if they cannot search for liquor without a warrant,

they might as well be discharged. It is impossible to get a

warrant to stop an automobile. Before a warrant could be

secured the automobile would be beyond the reach of the officer,

with its load of illegal liquor disposed of.lO

_.

The controversy was resolved between the two Houses in a compromise. An

officer was punished who, "searched a 'private dwelling' without a warrant,"

and sanctions were also to be used against an officer who searched any

"other building or property, where and only where, he makes the search

without a warrant, maliciously and without probable cause." 11 Chief Justice

Taft reasoned:

In other words, it left the way open for searching an automobile,

or vehicle of transportation, without a warrant, if the search

was not malicious or without probable cause. The intent of Congress

to make a distinction between the necessity for a search warrant

in the searching of private dwellings and in that of automobiles

and other road vehicles in the enforcement of the Prohibition Act

is thus clearly established by the legislative history of the

Stanley Amendment. Is such a distinction consistent with the

4th Amendment? We think that it is. The 4th Amendment does not

denounce all searches or seizures, but only such as are unreasonable.l2

The Carroll Court took a survey of the leading search and seizure

cases and found that none of them ruled on the validity of a warrantless

seizure of contraband in a moving vehicle. The majority then laid their

cards on the table, not knowing at the time that almost sixty years of

confusion would follow:

On reason and authority the true rule is that if the search and

seizure without a warrant are made upon probable cause, that is,

4

upon a belief, reasonably arising out of circumstances known to

the seizing officer, that an automobile or other vehicle contains

that which by law is subject to seizure and destruction, the

search and seizure are valid.l3

The majority, .. having established that contraband goods concealed and

illegally transported in an automobile or other vehicle may be searched

without a warrant, .. 14 now had to define· the circumstances under which such

a search could be made. The Court concluded that it would be manifestly

unreasonable to permit law officers to stop every automobile solely on the

. grounds they might find contraband. For road trave 1ers have a right to

free passage without interruption or search unless there is known to a

competent officer authorized to search, probably cause for believing that

their vehicles are carrying contraband ... 15 The majority stated:

The measure of legality of such a seizure is, therefore, that the

seizing officer shall have reasonable or probable cause for

believing that the automobile which he stops and seizes has

contraband liquor therein which is being illegally transported . • •

_the line of distinction between legal and illegal seizure gives

the owner of an automobile in absence of probable cause, a right

to have restored to him the automobile; it protects him . . •

from use of the liquor as evidence against him . . . On the

other hand, in a case showing probable cause, the government

and its officials are given the opportunity to make the

investigation necessary to trace reasonably suspected contraband

goods and to seize them. Such a rule fulfills the guaranty of

the 4th Amendment. In cases where the securing of a warrant is

reasonably practicable, it must be used . . . In cases where

seizure is impossible except without warrant, the seizing officer

acts unlawfully and at his peril unless he can show the court

probable cause.l6

The Court refused to accept Carroll's argument that a search and

seizure is only justified if one has been arrested. Chief Justice Taft

declared the search did not have to be incident to arrest:

The right

to search and the validity of the seizure are not dependent on the right

to arrest. They are dependent on the reasonable cause the seizing officer

has for belief that the contents of the automobile offend against the law ... 17

Having determined that the standard for the automobile exception to

the Fourth Amendment's warrant requirement was the existence of probable

cause, the Court went on to precisely define the term. Quoting the earlier

case of Stacey v. Emery, 18 the Court said:

lf the facts and circumstances

before the officer are such as to warrant a man of prudence and caution in

believing that the offense has been committed, it is sufficient ... 19 The

11

11

11

5

majority had no problem in determining that probable cause existed against

Carroll, due to the fact that the geographic area surrounding the traffic

stop was an active center for the transportation of liquor, and because the

defendants were known to be "bootleggers." Carroll's conviction was affirmed,

and the black letter law rule that a warrantless search of an automobile

for concealed contraband is permissible upon probable cause.J was firmly

established--or so it seemed.

Forty-five years after Carroll, the Supreme Court decided the case of

Chambers v. Maroney. 20 After the second armed robbery ~ithin a week, the

police were given a description of·. the robber$'

car and of their clothing.

.

The police then stopped a car which met the description and which was

carrying four men and the described clothing. The men were arrested and the

car was taken to the station house where the police conducted a warrantless

search of the car finding guns, ammunition, and property stolen in the

robberies. At a Pennsylvania state court trial the evidence found in the

car search was admitted and petitioner was convicted. He petitioned for

.

habe~us corpus in the United States District Court for the Western District

'

'

of Pennsylvania. The District Court denied his petition without a hearing,

holding that the search of the car did not violate the petitioner's constitutional rights. The Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit affirmed. The

Supreme Court granted certiorari and affirmed.

~1r. Justice White delivered the majority opinion of the Court.

Peti:tioner claimed that the evidence taken from the vehicle search constituted

fruits of an illegal arrest. The majority disagreed, finding sufficient

probable cause for the police to stop the vehicle after getting a description

from observers of the robberies. However, the Court quickly pointed out

that the police station search of the car, conducted some time after the

arrest could not be justified as a search incident to arrest. The Court

quoted~the case of Preston v. United States: 21 "Once an accused is under

arrest and in custody, then a search made at another place, without a

22

warrant, is simply not incident to the arrest."

White distinguished

Preston and other cases from the situation presented in Chambers by pointing

out that in the present case the police had probable cause to both "arrest

the occupants of the station wagon; and to search the car for guns and

stolen money." 23

'

6

The Chambers opinion stated, however, that neither ·~carroll nor other

cases in this Court require or suggest that in every conceivable circumstance

the search of an auto even with probable cause may be made without the extra

protection for privacy that a warrant affords." 24

But the circumstances that furnish probable cause to search a

particular auto for particular articles are most often unforeseeable; moreover, the opportunity to search is fleeting since a car

is readily movable. Where this is true, as in Carroll and the case

before us now, if an effective search is to be made at any time,

either the search must be made immediately without a warrant or

·. the car itself must be seized and held without warrant for whatever

period is necessary to obtain a warrant for the search.25

(emphasis added)

The Chambers majority, acknowledging the Fourth Amendment's requirement

of a pre-search warrant issued by a magistrate on the issue of probable

cause, stated: "only in exigent circumstances will the judgement of the

police as to probable cause serve as a sufficient authorization for a

search." 26 (emphasis added) Of course, exigent circumstances exist in the

Carroll type stop, as the Court explains: "the car's contents may never be

found again if a warrant must be obtained." 27

But what are the "exigent circumstances" when the suspects are in

custody and the automobile is safely guarded at the police station? If the

police had probable cause to arrest the occupants, then surely a magistrate

would find probable cause and issue a warrant to search the vehicle. If

the car is safe at the station house, why not require the police to wait

: for a warrant before commencing search? In a classic Supreme Court excerpt,

the Chambers' majority advocated:

Arguably, because of the preference for a magistrate's judgement,

only the immobilization of the car should be permitted until a

search warrant is obtained; arguably, only the "lesser" intrusion

is permissible until the magistrate authorizes the "greater." But

which is the "greater" and which is the lesser intrusion is a

debatable question . . . For constitutional purposes, we see no

difference between on the one hand seizing and holding a car before

presenting the probable cause issue to a magistrate and on the

other hand carrying out an immediate search without a warrant.

Given probable cause ~o search, either course is reasonable under

the Fourth Amendment. 8

With the above statement, the Court created what is now known as the

Carroll-Chambers rule. This doctrine, stripped to its bare essentials, gives

the police two options. First, if the police have probable cause and exigent

11

~-4('

00 (- ... • IJ

~.

-~

11

7

circumstances exist (i.e., the vehicle is movable, the occupants are alerted,

etc.) then pursuant to Carroll the vehicle may be searched at the scene.

Why did the police not follow this first option in the present case? The

Court explains in a footnote:

lt was not unreasonable in this case to

take the car to the station house. All occupants in the car were arrested

in a dark parking lot in the middle of the night. A careful search at that

. t

.

.

29

po1n

was 1mpract1cal.''

The second option, created by the Chambers opinion,

is that the on-the-scene probable cause to search continues in the car to the

station house:

. . . unless the Fourth Amendment permits a warrantless seizure

of the car and the denial of its use

anyone until a warrant

is secured. In that event there is little to choose in terms of

practical consequences between an immediate search without a

warrant and the car's immobilization until a warrant is obtained. 30

11

to

Chambers appeared to be a great victory for the police, as once again

the Court has upheld the police officer's determination of probable cause

as a substitute for the magistrate. Was the necessity for a magistrate in

automobile cases being written out of the Fourth Amendment? The Chambers

opinion was not without its critics. Professor Wayne LaFave, considered

the premiere authority on search and seizure, offered these comments:

This passage from Chambers is remarkable . . • As for the assertion

that it is a debatable question" whether seizure of the vehicle

is a lesser intrusion than a search of its interior, no clear

explanation was offered as to why this is s~ nor was any reference

made to it in United States v. Van Leeuwen, 1 in which a somewhat

similar question was not found at all debatable a few months

earlier. (In Van Leeuwen, a unanimous Court held that the proper

course of action, given probable cause to search packages placed

in the mails, was to withhold routing and delivery of the packages

for the brief period necessary to obtain a search warrant). Nor

did the Court suggest what Variety of circumstances .. could make

holding of the vehicle until a warrant was obta~2ed a greater

intrusion than an immediate warrantless search.

Justice Harlan, dissenting in Chambers, believes that the Court has

gone too far in their extension of Carroll:

I believe it clear that a warrantless search involves the greater

sacrifice of Fourth Amendment values . . • the lesser intrusion

will almost always be the simple seizure of the car for the period-perhaps a day--necessary to enable the officers to obtain a search

warrant . . . Since the occupants themselves are to be taken into

custody, they will suffer minimal further inconvenience from the

temporary immobilization of their vehicle ••. Indeed, I believe

this conclusion is implicit in the opinion of the unanmious Court

in Preston. The Court concluded (in Preston) that no (Fourth

11

11

8

Amendment) exception was available, stating that "since the men

were under arrest at the police station and the car was in police

custody at a garage, there was no danger that the car would be

m?ved out of the locality or jurisdiction • . . The Court now

d1scards the approach taken in Preston, and creates a special rule

for ~utomobile searches that is seriously at odds with generally

appl1ed Fourth Amendment principles.33

The Chambers majority did take the trouble to distinguish Preston on

the ground that in the Preston case, "the arrest was for vagrancy; it was

apparent that the officers had no cause to believe that evidence of crime

was concealed in the auto." 34 The Court is saying that Preston may have had

the exigency of mobility, but not probable cause to search. Under the

Carroll-Chambers rule, both criteria are essential to a valid warrantless

search to be conducted either at the scene or at the station house.

In fact, the next major Supreme Court case, Coolidge v. New Hampshire, 35

found the opposite result than in Preston. In Coolidge, the Court decided

the police had probable cause, but not exigent circumstances to conduct a

station house search. Coolidge was a confusing opinion, which ended up with

only a plurality of Justices, but it negated the fear some critics had that

•_ ·r , -vehicles\~ay~~iways be subject to search without a search warrant. The police

in Coolidge were several weeks into the investigation of a murder and the

defendant was a prime suspect. After arresting the defendant, the police

then seized his vehicle and searched it later at the station house; in both

situations no warrant had been issued. The plurality distinguished Coolidge

from the Carroll-Chambers rule on the ground that in the present case the

police had knowledge of the probable role of the automobile in the commission

of the crime. The defendant knew he was under investigation and could have

easily destroyed any evidence present in the car, but instead left it parked

in his driveway. The plurality stated:

The word "automobile .. is not a talisman in whose presence the

Fourth Amendment fades away and disapears . . • In short, by no

possible stretch of the legal imagination can this be made into

a case where "it was not practicable to secure a warrant," and the

automobile exception, despite its label, is simply irrelevant.

Since Carroll would not have justified a warrantless search of

the Pontiac at the time Coolidge was arrested, the later search

at the station house was plainly illegal, at least so far as the

automobile exception is concerned. Chambers is of no help . . .

since that case held only that, where the police may stop and

search an automobile under Carroll, they may also seize it and

search it later at the police station. Rather, this case is

controlled by Dyke v. Taylor. There the police lacked probable

~

~'

'--II

oo~--fl

-·- -~ \..)

9

cause to seize or search the defendant's automobile at the time

of his arrest, and this was enough by itself to condemn the

subsequent search at the station house. Here there was probable

cause, but no exigent circumstances justified the police in

proc~eding without a warrant. As in_Qyke, the later search at the

stat1on house was therefore illegal.~

Justice White, dissenting in Coolidge, was critical of the plurality's

decision. He points out how difficult the rule for search and seizures of

automobiles, particularly the mobility doctrine, has become:

The majority now approves warrantless searches of vehicles in

motion when seized. On the other hand, warrantless, probable cause

searches of parked but movable vehicles in some situations would be

valid only upon proof of exigent circumstances justifying the

search. Although I am not sure, it would seem that, when the

police discover a parked car that they have probable cause to

search, they may not immediately search but must seek a warrant.

But if before the warrant arrives, the car is put in motion by

its owner or others, it may be stopped and searched on the spot

or elsewhere •.• Although (Carroll and Chambers) may, as the Court

argues, have involved vehicles in motion prior to their being

stopped and searched, each of them approved the search of a vehicle

that was no longer moving and, with the occupants in custody, no

more likely to move than the unattended but movable vehicle parked

on the street or in the driveway of a person's house. In both

situations the probability of movement at the instance of family

or friends is equally real and hence the result should be the same

whether the car is at rest or in motion when it is discovered.37

The Court had another opportunity to define the exigent circumstances

problem in Cardwell v. Lewis. 38 In Cardwell the defendant was arrested

,at the police station and his car was subsequently seized from a nearby

parking lot. The search of the car differed from previous cases as it was

an exterior search for paint samples and tire threads. Once again, the Court

was unable to come up with a majority of Justices. The plurality opinion,

authored by Blackmun considered the issue to be: 11 whether the examination

of an automobile's exterior upon probable cause invades a right to privacy

which the interposition of a warrant requirement is meant to protect ... 39

40

The plurality expressed the fundamental view of Warden v. Hayden

that instead of property rights, the Fourth Amendment's main concern is the

/

protection of individual privacy. Blackmun defended the automobile exception

to the Fourth Amendment by stating: .. Generally, less stringent warrant

requirements have been applied to vehicles ... 41 He then continued to justify

the underlying rationale of the automobile exception:

10

One has ~ lesser expectation of privacy in a motor vehicle

because 1ts function is transportation and it seldom serves

as one's residence or as the repository of personal effects.

A car has little capacity for escaping public scrutiny. It

travels public thoroughfares where its occupants and its contents

are in plain view.4Z

The plurality, setting up the argument that the exterior of an automobile

has no privacy interest, quoted Katz v. United States; 43 What a person

knowingly exposes to the public • . . is not a subject of Fourth Amendment

protection ... 44

11

After laying this Fourth Amendment foundation, the Court stated:

With the search limited to the examination of the tire on the

wheel and the taking of paint scrapings from the exterior of the

vehicle left in the public parking lot, we fail to comprehend what

expectation of privacy was infringed. Stated simply, the invasion

of privacy, if it can be said to exist, is abstract and theoretical.

Under circumstances such as these, where probable cause exists, a

warrantless examination of the exterior of a car is not unreasonable

under the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments.45

The plurality then addressed the exigent circumstances problem, as the

police had seized the car and made the exterior search at the station house.

We do not think that, because the police impounded the car prior

to the examination, which they could have made on the spot, there

is a constitutional barrier to the use of the evidence obtained

thereby. Under the circumstances of this case, the seizure itself

was not unreasonable.46

The opinion,having gone this far, had only the choice to compare the present

case with Chambers and not Coolidge. In distinguishing Coolidge, the plurality

remarked that, Since the Coolidge car was parked on the defendant's driveway,

the seizure of that automobile required an entry upon private property ... 47

However, the car in Chambers was stopped and seized on a public highway.

This is obviously a weak, almost ridiculous argument. The fact remains that

in both Coolidge and the present case, the cars were parked and the defendants

were already under arrest. The exigency of someone moving the vehicle, or

getting to evidence before the vehicle was seized, seems to be more imperative in Coolidge than in Cardwell. In the former case, which required a

warrant before station house search, the car was in a private driveway

where it was easily accessible to family or friends. In Cardwell, which

did not require a warrant, the car was left by the defendant in a public

downtown parking lot, arguably a lesser exigency, since family and friends

were presumably farther away. And of course, which the Court refuses to

11

,~0·"\

00 -.....

~

I

,' •

..

~-

f

11

admit, once a vehicle is seized and is under police guard at the station

house, absolutely no exigent circumstances exist at all. There is no

reason, except for administrative convenience, why a warrant need not be

procured post seizure of the vehicle. However, with the fiction of Chambers,

that the exigency continues to the station house, the Court forced itself

to argue on tenuous grounds: namely, by distinguishing cases according to

the vehicle's mobility or immobility/or whether seized on public or private

places.

The petitioner in Cardwell argued his case was consistent with Coolidge,

as probable cause to search the car had existed in both cases long before

the arrests. Also, in both cases, the car was seized after the defendants

were in police custody. Under these circumstances what kind of emergency

conditions existed to justify a warrantless search and seizure? The plurality

responded:

Assuming that probable cause previously existed, we know of no case

or principle that suggests that the right to search on probable

cause and the reasonableness of seizing a car under exigent circumstances are foreclosed if a warrant was not obtained at the first

practicable moment. Exigent circumstances with regard to vehicles

are not limited to situations where probable cause is unforeseeable

and arises only at the time of arrest. The exigency may arise at

any time, and the fact that the police might have obtained a warrant

earlier does not negate the possibility of a current situation's

necessitating prompt police action.4 1

As Professor LaFave summarizes in his Search and Seizure treatise:

The four Cardwell dissenters would have none of this. They objected

(i) that even if there had been no search of the car, the fact

remained that the car had been seized, an activity also encompassed

within the Fourth Amendment's protections; (ii) that the question was

whether the vehicle was movable, thus implying that it was not relevant that the car was found on public rather than private property,

and (iii) that there was no reason whatsoever why the police could

not have armed themselves with a search warrant in advance.48

Although both Coolidge and Cardwell can be distinguished from Chambers

by the mobility doctrine, it is harder to distinguish the two between themselves. The only real distinction between the two searches is that the

Cardwell car itself was not searched, only its exterior. The only distinction

for seizure purposes between the two is on the private/public grounds argument.

If this seems unsatisfactory to answer why Coolidge required a warrant and

Cardwell did not, we must take comfort in the fact that neither case received

the votes of five Supreme Court Justices.

12

The next major Supreme Court opinion was Texas v. White 49 in 1975.

A majority per curiam opinion added nothing new to the law, but solidified

the Chambers rule. Justice Marshall dissented, believing that the majority

had created a black letter rule where none had existed before:

C~ambers did not hold, as the Court suggests, that police officers

w1th probable cause to search an automobile on the scene where it

was stopped could constitutionally do so later at the station house

without first obtaining a warrant. Chambers simply held that to

be the rule when it is re~6onable to take the car to the station

house in the first place.

PART TWO:

CONTAINERS

As the Carroll opinion mandated, a warrantless automobile search

where the police have probable cause, includes a search for concealed contraband. Therefore, a majority of state courts and lower federal courts considered

the scope of warrantless automobile searches to extend to containers, i.e.,

suitcases, paper bags, etc., found within the vehicle. This practice was

questioned by the Supreme Court in the 1977 case of United States v. Chadwick. 51

In Chadwick, a locked footlocker had been seized by federal agents

from the open trunk of a parked automobile during the arrests of those who

had been in possession of the footlocker at the automobile's location outside

a train terminal. The agents transported the footlocker to the federal

building in Boston, Massachusetts. Acting with a probable cause belief that

the footlocker contained contraband, but without a warrant, the agents opened

the locker and discovered large quantities of marijuana. The District Court

granted defendant's motion to suppress, holding that warrantless searches

were per se unreasonable under the Fourth Amendment unless they fell within

-some established exception to the warrant requirement; and that the search

of the footlocker without a warrant was not justified under either the

exception for searches of automobiles or for searches incident to arrest.

The United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit affirmed the

District Court. On certiorari, the United States Supreme Court affirmed.

In the majority opinion, authored by Chief Justice Burger, the Court

quickly pointed out that once the footlocker had been lawfully seized, no

exigent circumstances existed which would permit a warrantless search:

There was no risk that whatever was contained in the footlocker

tru~k would be removed by the defendants or their associates.

-·-·--~-

13

The agents had no reason to believe that the footlocker contained

explosives or other inherently dangerous items, or that it contained

evidence which would lose its value unless the footlocker were

opened at once • . . it is not contended that there was any exigency

calling for an immediate search.52

The Court then went on to discuss the Government's claim that the

Warrant Clause of the Fourth Amendment protects only interests traditionally

identified with the home. The Government had argued that only homes, offices,

and private communications implicate the Fourth Amendment because of the

highly valued privacy interest associated with those items. The Government

reasoned that all other situations had a lesser privacy interest and

therefore the reasonableness of a search and seizure depended solely on

the presence or absence of probable cause. The majority opinion struck

down this position forcefully, but acknowledged the need for a historical

review:

As we have noted before, the Fourth Amendment protects people, not

places; more particularly, it protects people from unreasonable

government intrusions into their legitimate expectations of

privacy . . • it would be a mistake to conclude, as the Government

contends, that the Warrant Clause • . . intended to guard only

against intrusions into the home •.• There is a strong historical

connection between the Warrant Clause and the initial clause of

Fourth Amendment, which draws no distinction among "persons, houses,

papers, and effects" in safeguarding against unreasonable searches

and seizures. Moreover, if there is little evidence that the

Framers intended the Warrant Clause to operate outside the home,

there is no evidence at all that they intended to exclude from

protection of the Clause all searches occurring outside the home . • .

Our fundamental inquiry in considering Fourth Amendment issues is

whether or not a search or seizure is reasonable under all the

circumstances . • • Once a lawful search is begun, it is also far

more likely that it will not exceed proper bounds when it is done

pursuant to a "judicial authorization" particularly describing the

place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized. Further,

a warrant assures the individual whose property is searched or

seized of the lawful authority of the executing officer, his need

to search, and the limits of his power to search. Just as the

Fourth Amendment protects people, not places," the protections a

judicial warrant offers against erroneous governmental intrusions

are effective whether applied in or out of the home.53

Burger then voiced the opinion that the respondents in this case

expected the contents of the footlocker to remain free from public scrutiny.

They had double locked the footlocker and had placed "personal effects"

inside. The Court analogized this situation as the equivalent of a homeowner locking his doors to keep out trespassers. Upon this premise the

11

. ..

00 1~0~

-

~.

'oJ

14

majority believed the respondents were entitled to the protection of the

Warrant Clause, and therefore the search of the footlocker was unreasonable.

Obviously Chadwick is not a per se automobile search. It is at best

remotely an automobile search. The footlocker was in the trunk of the car

for only a few moments, the car trunk was not closed, and the vehicle was

never in motion. Nevertheless, the Court was faced with the automobile

exception argument as the Government advocated that the rationale behind

automobile cases permitted warrantless searches of luggage. The majority

agreed that luggage, as well as automobiles, are effects for Fourth Amendment purposes. Beyond that, however, the analogy ended.

But this Court has recognized significant differences between

motor vehicles and other property which permit warrantless searches

of automobiles in circumstances in which warrantless searches would

not be reasonable in other contexts .•• The factors which diminish

the privacy aspects of an automobile do not apply to respondent's

footlocker. Luggage contents are not open to public view ••.

Unlike an automobile, whose primary function is transportation,

luggage is intended as a repository of personal effects. In sum,

a person's expectations of privacy in personal luggage are substantially greater than in an automobile.54

The Chadwick opinion presents some interesting speculations--basically

because it provides no answers and certainly no guidance for law enforcers

or the courts. Why the Court bothered to distinguish the automobile exception from Chadwick's luggage, without mentioning what would happen if the

luggage had been seized from a moving vehicle, is one of the great mysteries

of irresponsible Supreme Court case law. Chadwick does tell us that luggage

has a greater privacy interest than an automobile. Thus a warrant is

required before luggage can be searched after it has been lawfully seized.

But with what one can determine from Chadwick, the above rule only applies

to luggage which is wholly isolated from automobiles; i.e., in situations

where the police arrest a defendant who is walking and carrying a suitcase.

What then is the rule when the police, acting with probable cause, discover

a container in their warrantless search of an automobile at the scene?

Two possibilities readily come to mind: First, by negative inference, it

seems that the Court is saying that if the facts present in Chadwick had

fallen within the automobile cases, i.e., the footlocker had been in a

moving or readily movable vehicle in a public place, where the police had

probable cause and exigent circumstances had existed, then even though the

·--~-

Oo

'

. ..

;·•,,.C\.

.,.

..

4WII

15

car could have been searched on the spot without a warrant (Carroll}, or

seized and taken to the station house and searched without a warrant

(Chambers), that the footlocker in the car would still require a warrant

before it could be searched because of its greater privacy interest. Or,

the second possibility: Is the opinion in Chadwick saying that because of

the facts presented it was not an automobile case and since there were no

exigent circumstances a warrant was required; thus leaving open the possibility

that if the footlocker was sufficiently connected with the vehicle it would

have become an automobile case; and therefore if exigent circumstances and

probable cause existed to search the vehicle,.then the locker also could

have been searched at the scene or later at the station house?

Unfortunately, the majority's final proposition serves only to totally

confuse the issue:

In our view, when no exigency is shown to support the need for an

immediate search, the Warrant Clause places the line at the point

where the property to be searched comes under the exclusive

domain of police authority. Respondents were therefore entitled

to the protection of the Warrant Clause with the evaluation of a

...

neutral magistrate, before thei5 5privacy interests in the contents

of the footlocker were invaded.

,

••

t

•

Again, by negative inference the Court seems to imply that if exigent

circumstances had existed the result may be indeed different. Carroll and

Chambers only allow warrantless automobile searches· when both probable cause

and exigent circumstances (the dynamic duo) are present. Hypothetically,

~then .containers in vehicles could be fully searched without a warrant whenever

._,.

the automobile exception is in full force. But the Court saturated the

entire opinion in Chadwick discussing the omnipotent privacy interests in

luggage! Without overly editorializing, this author found the majority

opinion in Chadwick to be ambiguous, vague, and virtually worthless.

Professor LaFave is equally puzzled with the application of Chadwick

to automobiles:

As the Supreme Court put it, the district court "saw the relationship between the footlocker and Chadwick's automobile as merely

coincidental." It is fair to say, therefore, that Chadwick does

not settle the question of whether containers in a car may be

searched in an otherwise lawful warrantless search of a vehicle;

a majority of the Court has neither embraced nor repudiated the

claim of the Chadwick dissenters that "if the agents had postponed

the arrest just a few minutes longer until the respondents started

to drive away, then the car could have been seized, taken to the

agent's office, and all its contents--including the footlocker-searched without a warrant. u56

16

Yes, the dissenters, Blackmun joined by Rehnquist, were more than

subtly cynical of the majority's position in Chadwick. But what is the

answer? The majority, jumping on the strained nexus between the footlocker

and the vehicle, ducked the issue. The result was total confusion and the

1979 case of Arkansas v. Sanders. 57

In Sanders, Little Rock, Arkansas, police officers placed the airport

under surveillance acting upon a reliable informant's tip that a suspect

would arrive on a flight and retrieve a green suitcase containing marijuana.

The suspect picked up the suitcase from the airline's luggage service and

placed it in the trunk of a taxicab. The police, apparently briefed on the

Chadwick decision, waited until the taxi began to drive away before they

pulled it over. Upon the officer's request,the

taxi driver opened the

_.....

trunk and the policemen seized and opened the unlocked suitcase. The

officers discovered marijuana. At his state court trial, the defendant

moved to suppress the evidence obtained from the suitcase, contending the

search violated his Fourth Amendment rights. The trial court upheld the

lawfulness of the search and the defendant was convicted. On appeal, the

Supreme Court of Arkansas reversed the conviction, ruling that the trial

court should have suppressed the evidence because it was obtained through

an unlawful search of the suitcase. On certiorari, the United States Supreme

Court affirmed the decision of the Arkansas Supreme Court.

Justice Powell delivered the opinion for a majority of the Court.

The Court first defined the issue:

This case presents the question whether, in the absence of exigent

circumstances, police are required to obtain a warrant before

searching luggage taken SSom an automobile properly stopped and

searched for contraband.

(emphasis added)

From the first lines of the opinion, it appeared that the Court was contradicting itself. The majority stated that the automobile was properly stopped

and searched for contraband--thus implying under the Carroll-Chambers rule

that both probable cause and exigent circumstances were present. But the

Court said the issue was whether police could search luggage taken from an

automobile in the absence of exigent circumstances. The Court seemed to be

saying that while ·an exigency may exist to search the vehicle and even seize

it, no exigency is present regarding the enclosed container. This appears

to be a non sequitu~-it does not follow that emergency conditions exist to

Oll"n'"'

1_] '_:.

·,)

17

search the person, but not his pockets. The real issue the Court should

have addressed, since the vehicle fell within the exigent circumstances

doctrine, is whether in the presence of emergency conditions the police

are required to obtain a warrant before searching luggage~in an othe~~ise

permissible setting for a warrantless search of the vehicle. Unless the

Court is of the opinion, and as Sanders goes on to show they are, that

exigencies for automobiles (effects) and containers (effects) are to be

treated as two distinct phenomena, even when they are combined within the

same act, transaction, or occurrence.

The Sanders majority confessed.. they granted

certiorari due to the

.

confusion surrounding the Chadwick decision. Applying the facts in Sanders,

the Court found that the police did indeed have the requisite probable cause

to believe contraband was present in the taxi and were acting prudently to

stop the vehicle, search 'it, and seize the suitcase. The majority reasoned

that if the police after seizing the suitcase, had taken it to the station

house, and waited for a warrant before searching it, then everything would

have been constitutionally permissible. The Court stated:

A lawful search of luggage generally may be performed only pursuant

to a warrant. In Chadwick, we declined an invitation to extend

the Carroll exception to all searches of luggage, noting that

neither of the two policies supporting warrantless searches of

automobiles applies to luggage. Here, as in Chadwick, the officers

had seized the luggage and had it exclusively within their control

at the time of the search. Consequently, there was not the slightest

danger that the luggage or its contents could have been removed

before a valid search warrant could be obtained.59

The State had argued the search was proper, "not because the property

searched was luggage, but rather because it was taken from an automobile

60

lawfully stopped and searched on the street."

In effect, the State would have us extend Carroll to allow

warrantless searches of everything found within an automobile,

as well as of the vehicle itself . . . This Court has not had

occasion previously to rule on the constitutionality of a

warrantless search of luggage taken from an automobile lawfully

stopped. Rather, the decisions to d~te have involved searches

of some integral part of the automob1le.6 1

The Court cited cases dealing with the integral parts of automobiles

including glove compartments, passenger compartments, trunks, and behind

the upholstery of seats. The Court then held:

A closed suitcase in the trunk of an automobile may be as mobile

as the vehicle in which it rides. But as we noted in Chadwick,

'

.

18

the exigency of mobility must be assessed at the point immediately

before the search--after the police have seized the object to be

searche~ and have it securely within their control. Once police

~ave se1zed a suitcase, as they did here, the extent of its mobility

1s no way affected by the place from which it is taken. Accordingly,

as a general rule there is no greater need for warrantless searches

of lugga ge taken from automobiles than of luggage taken from other

places. 62

The majority seems to be saying, in the area of containers, the exigency

of mobility becomes eradicated at the point it is safely within the custody

of the police. The Court did not recognize any difference between the privacy

interest in a suitcase which had been taken from an automobile and one

taken from a variety of other places.

0ne is not less inclined to place

private, personal possessions in a suitcase merely because the suitcase is

to be carried in an automobile rather than transported by other means or

temporarily checked or stored ... 63 The Court stated forcefully:

Accordingly, the reasons for not requiring a warrant for the search

of an automobile do not apply to searches of personal luggage taken

by police from automobiles. We therefore find no justification for

the extension of Carroll and its progeny to the warrantless search

of one's personal luggage merely because it was in an automobile

lawfully stopped by the police.64

Sanders does have the advantage of creating a rule: a suitcase may be

lawfully seized without a warrant from an automobile if the requisite probable

cause and exigent circumstances exist, but before it can be searched a

warrant must be issued by a neutral magistrate. However, the opinion does

have its shortcomings; specifically, does the new rule extend to all containers

in automobiles, or just those which are universally accepted as private

repositories for personal effects? In a well reasoned dissent in Sanders,

Justice Blackmun joined by Rehnquist lays a heavy verbal assault upon the

majority:

The Court today goes farther down the Chadwick road, undermines the

automobile exception, and, while purporting to clarify the confusion

occasioned by Chadwick, creates in my view, only greater difficulties

for law enforcement officers, for prosecutors, for those suspected of

criminal activity, and, of course, for the courts themselves. Still

hanging in limbo, and probably soon to be litigated, are the briefcase, the wallet, the package, the paper bag, and every other kind

of container.6~

The dissenters agree with the State's argument in both Chadwick and

Sanders; if contraband may be searched without a warrant, then luggage and

other containers deserve the same treatment. Blackmun argues:

11

19

The luggage, like the automobile transporting it, is mobile. And

the e~pe~t~tion of privacy in a suitcase found in the car is probably

not s1gn1f1cantly greater than the expectation of privacy in a locked

glov~ compartment or trunk •.• Moreover, the additional protection

provlded_by a search warrant will be minimal. Since the police, by

hypothes1s, have probable cause to seize the property, we can assume

that a warrant will be routinely forthcoming in the overwhelming

majority of cases.66

Although the search incident to arrest doctrine is beyond the scope of

this work, the following excerpt from Blackmun's dissent in Sanders is valuable

in pointing out how confusing the law for warrantless searches of automobiles

has become:

The impractical nature of the Court's line drawing is brought into

focus if one places himself in the position of the policeman confronting an automobile that properly has been stopped. In approaching

the vehicle and its occupants, the officer must divide the world of

personal property into three groups. If there is probable cause to

arrest the occupants, then under Chimel v. California, he may search

objects within the occupant's immediate control, with or without

probable cause. If there is probable cause to search the automobile

itself, then under Carroll arid Chambers the entire interior area of

the automobile may be searched, with or without a warrant. But under

Chadwick and the present case, if any suitcase-like object is found

in the car outside the immediate control area of the occupants, it

cannot be searched, in the absence of exigent circumstances, without

a warrant . • . Or suppose the arresting officer opens the car's

trunk and finds that it contains an array of containers--an orange

crate, a lunch bucket, an attache case, a dufflebag, a cardboard box,

a backpack, a totebag, and a paper bag. Which of these may be searched

irrmediately, and which are so "personal" that jhey must be impounded

for future search only pursuant to a warrant? 6

Professor LaFave believes the essence to Chadwick and Sanders is:

"a warrant is needed to search a container found in

, a vehicle only when the

container is one that generally serves as a repository for personal effects

or that has been sealed in a manner manifesting a reasonable expectation

68

that the cont~nts will not be open to public scrutiny."

Part of LaFave's

analysis must rest on what the Court said in footnote 13 in the Sander's

majority opinion:

Not all containers and packages found by police during the course

of a search will deserve the full protection of the Fourth Amendment.

Thus some containers (for example a kit of burglar tools or a gun

case) by their very nature cannot support any reasonable expectation

of privacy because their contents can be inferred from their outward

appearance. Similarly, in some cases the contents of a package will

be open to "plain view .. thereby obviating the need for a warrant.69

Obviously, such irrational line drawing, utterly devoid of any practical

utility, could not last for long. The Court had to go one way or the other,

20

and in 1981\in Robbins v. California, 70 a plurality op1n1on implemented

a blanket warrant requirement on containers-~all containers. In Robbins,

California Highway Patrol officer~ stopped an individual's station wagon

because he had been driving erratically. The officers smelled marijuana

and placed the suspect under arrest. They then opened the tailgate of the

station wagon, discovered the luggage compartment and found two packages

wrapped in green opaque plastic. The officers opened the packages and

discovered they contained several bricks of marijuana. The defendant moved

to suppress the evidence but was convicted in his state court trial. The

California Court of Appeals affirmed the conviction, holding that the warrantless search was permissible as the officers could have inferred the packages

contained marijuana due to their outward appearance. On certiorari, the

United States Supreme Court reversed. Although unable to form a majority

opinion, five members of the Court agreed the search violated the Fourth

Amendment.

Justice Stewart authored the ·plurality opinion. He quickly struck

down the State's claim that the automobile exception justifies a search of

closed containers by relying on Chadwick and Sanders.

Those cases made cl~ar . . . that a closed piece of luggage found

in.a lawfully searched car is constitutionally protected to the

same extent as are closed pieces of luggage found anywhere else.

The respondent, however, proposes that the nature of a container

may diminish the constitutional protection to which it otherwise

would be entitled--that the Fourth Amendment protects only containers

•·used to transport persona 1 effects... By persona 1 effects the

respondent means property worn on or carried about the person or having

some intimate relation to the person.71

The plurality would have none of this--the Fourth Amendment protects

effects whether considered personal or impersonal. The crucial question,

according to the plurality, is whether the individual intended those effects

to be kept private, free from public scrutiny. 0nce placed within such a

container, a diary and a dishpan are equally protected by the Fourth Amendment ... 72 Once an individual intended an effect to be private by placing it

in a container, the kind of container he chose was simply irrelevant. In

Stewa r+' s words:

. . . even if one wished to import such a distinction into the

Fourth Amendment, it is difficult if not impossible to perceive

any objective criteria by which that task might be accomplished.

What one person may put into a suitcase, another may put into a

-.. .I

11

11

21

~ap~r

bag. And as the disparate results in the decided cases

1nd1cate, no court, no constable, no citizen, can sensibly be

as~ed to dis~inguish the relative "privacy interests .. in a closed

su1tcase, br1efcase, portfolio, duffle bag, or box./3

The State then tried to argue that under footnote 13 of Sanders,

{which excluded certain containers from full Fourth Amendment protection),

the packages fell within the plain view exception. The California appellate

court had stated: "any experienced observer could have inferred from the

appearance of the packages that they contained bricks of rnarijuana." 74

The plurality struck down this contention also:

Expectations of privacy are established.by general social norms,

and to fall within the second exception.of the footnote in question

a container must so clearly announce its contents, whether by its

distinctive configuration, its transparency, or otherwise, that its

contents are obvious to an observer. If indeed a green plastic

wrapping reliably indicates that a package could only contain

marijuana, that fact was not shown by the evidence . . • We reaffirm

today that such a container may not be opened without a warrant,

even if it is found during the course of the lawful search of an

automobile.75

··.

Justice Powell concurred·in the judgement stating that he could not

join the plurality as the new "bright line" went too far and was not supported

by prior decisions.

It would require officers to obtain warrants in order to examine

the contents of insubstantial containers in which no one had a

reasonable expectation of privacy . . • While the plurality's blanket

warrant requirement does not even purport to protect any privacy

interest, it would impose substantial new burdens on law enforcement.

Confronted with a cigar box or a ·Dixie cup in the course of a probable

cause search of an automobile for narcotics, the conscientious policeman would be required to take the object to a magistrate, fill out

the appropriate forms, await the decision, and finally obtain the

warrant. Suspects or vehicles normally will be detained while the

warrant is sought. This process may take hours, removing the officer

from his normal police duties. Expenditure of such time and effort,

drawn from the public's limited resources for detecting or preventing

crimes, is justified when it protects an individual's reasonable

privacy interests •.• The aggregate burden of procuring warrants

whenever an officer has probable cause to search the most trivial

container may be heavy and will not be compensated by the advancement

of important Fourth Amendment v~~ues. The sole virtue of the

plurality's rule is simplicity.

It does appear that something is just not right with the Robbins

decision. The plurality has now carried Chadwick to its ultimate, but

unfortunately illogical~conclusion. The Court has gone away from the

''

,,n.•

-. ·--

00 --I ; ; \9

22

general societal definition of expectations of privacy and has replaced

it with an individual's definition of his expectation of privacy. The

difference is that between an accepted societal norm and an individual's

intention. Luggage, by its very definition and character.exemplifies on

J

its face an expectation of privacy. The same cannot be said of a Dixie

cup or package of gum. The problem is that no line can be drawn; it is

a short step down from the suitcase to the briefcase, but the downward

spiral conceivably could continue to the gum package. Equal protection

must have also played a part in the plurality's opinion: while the Chadwick

Court probably had the image of the individual's expectations of privacy

in his American Tourister three-suiter in mind, how could the Court give

him full Fourth Amendment protection and not the less fortunate individual

who carried his valuables in a Safeway grocery bag? However, the important

state interests in efficient law enforcement could ill afford to play this

game of semantics, and it was not long before the words of Justice Rehnquist,

dissenting in Robbins became a reality .

.i)

I would return to the rationale of Chadwick and Chambers and hold

that a warrant should not be required to seize and search any

personal property found in an automobile that may in turn be

constitutionally seized and searched without a warrant. I would

not abandon this reasonably 11 bright line 11 in search of another.77

It turned out that the Robbins dissneters did not have long to wait.

On June 1st, 19S2, the Court decided United States v. Ross. 78 In Ross,

:District of Columbia police officers acting upon an informant's tip that

the defendant was selling drugs out of his car, drove to the location,

stopped the car and arrested Ross. During a search at the scene, an officer

discovered a closed paper bag in the trunk of the car. Without a warrant,

the officer opened the paper bag and found that it contained heroin. The

officer drove the defendant's car to police headquarters where another

warrantless search of the trunk revealed a zippered leather pouch which

contained $3,200 in cash. In Federal District Court Ross moved to suppress

the evidence; his motion was denied and a conviction followed. The Court

of Appeals reversed, holding that while the officers had probable cause

to stop and search the car--including the trunk--without a warrant, they

were constitutionally forbidden to search either the paper bag or the pouch

without a warrant. The Court of Appeals stated their reasons for reversing

Ross's conviction:

00 ~0-"

I '- •• •'' •I

-. ' ~· • 'J

23

No s~ecific, well-delineated exception called to our attention

perm1ts the police to dispense with a warrant to open and search

.. unworthy container,s. Moreover, we believe that a rule under

which the validity of a warrantless search would turn on judgements

about the durability of a container would impose an unreasonable and

unmanageable burden on police and courts. For these reasons and

b~cause the Fourth Amendment protects all persons, not just those

w1th the resources or fastidiousness to place their effects in

containers that decisionmakers would rank in the luggage line,

we hold that the Fourth Amendment warrant requirement forbids the

warrantless opening of a closed, opaque paper bag to the same

extent that it forbids the warrantless opening of a small unlocked

suitcase or a zippered leather pouch./9

The majority opinion for the Supreme Co~rt was delivered by Justice

Stevens. He was joined by Chief Justice Burger, Blackmun, Powell, Rehnquist,

and O'Connor. With the retirement of Justice Stewart, and the addition of

Justice O'Connor, the dissenters in the Chadwick-Sanders-Robbins line of

cases now had a majority vote. From the Court's statement of the issue in

Ross, it became evident that a change was forthcoming:

(The issue is) the extent to which police officers who have legitimately stopped an automobile and who have probable cause to

believe that contraband is concealed somewhere within it--may

conduct a probing search of compartments and containers within

the vehicle whose contents are not in plain view.80

Ross was to be a scope decision; instead of delineating what kind of containers

deserved protection, the Court set out to define how far a search could extend.

For the Court realized the Court of Appeals' decision to reverse Ross's conviction had merit. It had become impossible to distinguish under Fourth

Amendment analysis, which containers were worthy of protection and which

were not. The time for clarification for all facets of the criminal justice

system had arrived.

For countless vehicles are stopped on highways and public streets

everyday and our cases demonstrate that it is not uncommon for

police officers to have probable cause to believe that contraband

may be found in a stopped vehicle. In every such case a conflict

is presented between the individual's constitutionally protected

interest in grivacy and the public interest in effective law

enforcement.81

The Court then began to lay its foundation for a new rule concerning

warrantless automobile search and se1zures. First, they relied on Carroll

and that the logic behind that decision applies as easily to 1982 automobile

cases as it did in 1925: The rationale justifying a warrantless search of

an automobile that is believed to be transporting contraband arguably applies

11

•,.

11

I

•

24

with equal force to any movable container that is believed to be carrying

82

an 1.11.1c1•t su bs t ance. u

Now the Court agreed with Justice Powell's concurring opinion in Robbins:

• • . ~he controlling question should be the scope of the automobile

except1on to the warrant requirement . . . a future case might present

a better opportunity for thorough consideration of the basic principles

in this troubled area.83

As the majority says in Ross, 11 the case has arrived ... Many observers

feel that the case should have arrived with Chadwick, or Sanders, or Robbins.

However, the Court with all its grace and elusiveness, tells us that Ross

is really a case of first impression:

Unlike Chadwick and Sanders, in this case (Ross) police officers had

probable cause to search respondent's entire vehicle. Unlike Robbins,

in this case the parties have squarely addressed the question whether,

in the course of a legitimate warrantless search of an automobile,

police are entitled to open containers found within the vehicle.

We now address that question. Its answer is determined by the scope

of the search that is authorized a~ the exception to the warrant

requirement set forth in Carroll.

The Court then reviewed a number of cases to determine what the scope

had been in the past. The Carroll search was found reasonable even though

federal agents were allowed to tear open the upholstery of the car itself.

The Ross majority stated that in Carroll:

the scope of the search was no

greater than a magistrate could have authorized by issuing a warrant based

on the probable cause that justified the search ... 85 In the Chambers station

house search, the police found evidence which was concealed in a compartment

under the dashboard.

No suggestion was made that the scope of the search (in Chambers)

was impermissible. It would be illogical to assume that the outcome

of Chambers--or the outcome of Carroll itself--would have been

different if the police had found the secreted container enclosed

within a secondary container and had opened that container without

a warrant. If it was reasonable for prohibition agents to rip open

the upholstery in Carroll, it certainly would have been reasonable

for them to look into a burlap sack stashed inside; if it was

reasonable to open the concealed compartment in Chambers, it would

have been equally reasonable to open a paper bag crumpled within it.

A contrary rule could produ~e absurd results inconsistent with the

decision in Carroll itself.86

By this time, things began to get rather dim for Mr. Ross and his

paper bag filled with heroin. For the Ross Court by resurrecting the Carroll

rule, mentioned part of the holding in that case which had been shuffled

11

,,n

.

00 .......

~

I

.•

_

.

25

under the rug in Chadwick-Sanders- and Robbins. In Carroll the scope of a

probable cause warrantless search extended to contraband goods concealed

within a vehicle. Besides the obvious concealed parts of an automobile

itself--glove compartments, trunks, etc.--where else to conceal contraband

than movable containers? As the Ross Court explained: Contraband goods

rarely are strewn across the trunk or floor of a car; since by their very

nature such goods must be withheld from public view, they rarely can be

placed in an automobile unless they are enclosed within some form of container ... 87 Upon this basis, the Court is really implying that Carroll

itself permitted the search of containers. For the same exigency presented

.

during the Carroll era--discovery of prohibited alcohol--is present today,

specifically furthering the goals of efficient law enforcement. The majority

felt the practical effect of Carroll would be destroyed if a legitimate

warrantless search for contraband did not include a search of containers

found during the course of such a search. As Justice Stevens noted:

the

decision in Carroll merely relaxed the requirements for a warrant on grounds

of impracticability. It neither broadened nor limited the scope of a lawful

search based on probable cause ... 88

When a legitimate search is underway, and when its purpose and its

limits have been precisely defined, nice distinctions between

closets, drawers, and containers, in the case of a home, or between

glove compartments, upholstered seats, trunks, and wrapped packages,

in the case of a vehicle, must give way to the interest in the prompt

and efficient completion of the task at hand. This rule §PPlies

equally to all containers, as indeed we believe it must. 8

11

~

'

,

11

With that statement, the Robbins decision died, and for all practical

purposes the eulogy was given for Sanders. From this point on, no distinctions

will be drawn as to whether a suitcase deserves more protection than a

package or a paper bag; any container that is the object of a legitimate

search is susceptible to such a search without a warrant. The Court did

remember Justice Stewart's statement in Robbins that the Fourth Amendment

provides protection to the owner of every container that conceals its

contents from plain view ... 90 However, the majority argued on how different

situations create different expectations of privacy and greater or lesser

•

Fourth Amendment protection:

The luggage carried by a traveler entering the country may be

searched at random by a customs officer; the luggage may be

searched no matter how great the traveler's desire to conceal

the contents may be. A container carried at the time of arrest

11

t'

26

ofte~ ~ay be ~e~rched without a warrant and even without any

spec1f1c susp1c1on concerning its contents. A container that

may concea~ the.object of a search authorized by a warrant may

b: opened 1mmed1ately; the individual's interest in privacy must

g1ve way to the magistrate's official determination of probable

cause. 91

The Court reasoned in the light of the above statement that an individual's

Jrivacy interest in respect to his vehicle and containers within it may have

to yield when faced with probable cause he is iilegally carrying contraband.

\s Carroll allowed an officer with probable cause to rip open the seats-~n obvious and flagrant infringement of privacy--how can the glove compartment,

the trunk, the suitcase, or the paper bag expect more? With such an analysis,

largely based on the definite revitalization and arguably extension of

Carroll itself, the majority in Ross deliver~d its holding, a new rule

regarding warrantless searches of automobiles.

The scope of a warrantless search based on probable cause is no

narrower--and no broader--than the scope of a search authorized by

a warrant supported by probable cause. Only the prior approval of

the magistrate is waived; the search otherwise is as the magistrate

could authorize. The scope of a warrantless search of an automobile

thus is not defined by the nature of the container in which the contraband is secreted. Rather, it is defined by the object of the search

and the places in which there is probable cause to believe that it may

be found. Just as probable cause to believe that a stolen lawnmower

may be found in a garage will not support a warrant to search an

upstairs bedroom, probable cause to believe that undocumented aliens

are being transported in a van will not justify a warrantless search

of a suitcase. Probable cause to believe that a container placed in

the trunk of a taxi contains contraband or evidence does not justify

a search of the entire cab . . . . • . • • . • • . . . . • . . • . .

If probable cause justifies the search of a lawfully stopped vehicle,

it justifies the search of every part of t~2 vehicle and its contents

that may conceal the object of the search.

Mr. Ross, the heroin pushing respondent, with his conviction reinstated,

was not the only critic of the Ross decision. Justice Marshall dissented,

a part of which follows:

The majority today not only repeals all realistic limits on

warrantless automobile searches, it repeals the Fourth Amendment

warrant requirement itself. By equating a police officer's

estimation of probable cause with a magistrate's, the Court

utterly disregards the value of a neutral and detached magistrate.

11

11

.................................

The Court derives satisfaction from the fact that its rule does

not exalt the rights of the wealthy over the rights of the poor.

A rule so broad that all citizens lose vital Fourth Amendment

protection is no cause for celebration.93

27

In conclusion, the Court has had to make some very difficult constitutional law decisions in trying to create a peaceful co-existence between the

automobile and the Fourth Amendment. However, that is the function of the

Supreme Court.

As the cases illustrate, automobiles and the Fourth Amend.,

ment are natural antagonists. The Court was forced to promulgate the

"automobile exception .. rather than lose incriminating evidence. As with any

'

exception, problems mount when courts try to define i~ without straying too

far from the rule. The ideal is to accord automobiles as much protection

as possible and yet realize to have a workable rule the mainstays of the

Fourth Amendment may have to bend. Chadwick-Sanders and Robbins applied too

much Fourth Amendment protection and created havoc fo'r 1aw enforcers and the

courts. Ross may have gone too far the other way. But Ross is a step in the