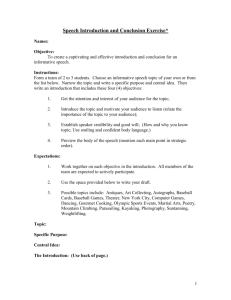

Coover`s Grand Slam by Crepeau.doc

advertisement

Coover’s Grand Slam By Richard Crepeau, Aethlon: the Journal of Sport Literature (VII: 1), Fall 1989, 113120. Everyone has his favorite novel. It speaks clearly to him, and resonates truths. Those working in sport literature have their favorites in the various sub-genre. For those caught up in baseball, choosing a favorite from among the many great baseball novels is not an easy task. But to me there is one cleat choice, Robert Coover's The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop. While in graduate school a friend, both historian and writer of fiction is there a difference?), mentioned to me that he had read about a baseball novel that seemed fairly interesting, and he rolled out the lengthy title. A few year<. later while in a Goodwill Store I was browsing the used book rack. On it was a copy of the UBA. I recognized the title and plucked it from the rack. On the inside cover I found a handwritten note which said simply: "To all us baseball nuts. Mad fun." I took this to be an omen. No, more a personal message. So 1 purchased the book for the princely sum of ten cents, and while standing in the store I opened and began to read: Bottom half of the seventh, Brock's boy had made it through another inning unscratched, one! two! three! Twenty-one down and just six outs to go! and Henry's heart was racing, he was sweating with relief and tension all at once, unable to sit, unable to think, in there, with them! Oh yes, boys, it was on! He was sure of it! More than just another ball game now: history! And Damon Rutherford was making it. Ho ho! too good to be true! And yes, the stands were charged with it, turned on, it was the old days all over again, and with one voice they rent the air as the Haymaker Star Hamilton Craft spun himself right off his feet in a futile cut at Damon's third strike-zingng! whoosh! zap! OUT! Henry laughed, watched the hometown Pioneer fans cheer the boy, cry out his name, then stretch-not just stretch-leap up for luck. He saw beers bought and drunk, hot dogs eaten, timeless gestures passed. Yes, yes, they nodded, and crossed their fingers and knocked on wood and rubbed their palms and kissed their fingertips and clapped their hands, and laughed how they were all caught up in it, witnessing it, how he was all caught up in it, this great ball game, event of the first order, tremendous moment: Rookie pitcher Damon Rutherford, son of the incomparable Brock Rutherford, was two innings-six outs from a perfect game! Henry, licking his lips, dry from excitement, squinted at the sun high over the Pioneer Park, then at his watch: nearly eleven, Diskin's closing hours. So he took the occasion of this seventh-inning hometown stretch to hurry downstairs to the delicatessen to get a couple sandwiches. Might be a long night: the Pioneers hadn't scored off old Swanee Law yet either. (9) 1 find it hard to believe now, having read this novel over and over again, that on first reading l was well into it before I realized that J. Henry Waugh was playing a dice game, and not witnessing the real thing. That first paragraph is so powerful that I still get caught up in the action of the game in much the same way that J. Henry Waugh did. The power of the writing , with Coover getting so much into this opening few words, wraps the excitement of the moment a and t symbols and rituals of the game Coover's treatment of baseball clearly speaks to me, and it seems to me that he captures the essence of the game, especially from the point of view of the fan. As John Steinbeck noted, "Baseball is not a sport or a game or a contest. It is a state of mind."' And it is the mind of the game that Coover is most skilled at presenting, revealed within J. Henry Waugh's mind which is increasingly dominated by baseball. The mind of baseball is Coover's overarching theme. And although the UBA is Henry’s peculiar brand of baseball, it carries many of the marks of the stadium rather than a board game. The differences between them are minimal. Baseball is baseball. Content overwhelms form. At the heart of the novel is Henry's total involvement with his creation, which is nothing less than a complete baseball universe. The UBA carries al l the marks of a baseball league with a full complement of teams; rosters of players; career statistics; the folklore and legends of the league; and a full history of each season and offseason. There is even a multi-volumed history of the Universal Baseball Association. Henry keeps copiously detailed records including notations of retirements and deaths with appropriate obituaries. The UBA is an eight-team league, playing an eighty-four game schedule. Over the years while rolling through the seasons as both fan and baseball historian, it has seemed tome that at the heart of the game is a rhythmic pattern, present in each inning, each game, each season. It is probably most obvious in the seasonal pattern: Each spring even the writers covering the worst teams generated some hope, sometimes sustaining it into the early days of the season. Often some poor team might have a brief spurt in the spring and win maybe eight or ten games, which set off even greater optimism. But slowly, as the weeks and months passed, disillusionment set in, first for the worst teams, then, eventually, it came for all but the pennant winners. Resignation to defeat came in the fall as the last hopes of the contenders faded. Some had already been overcome in the heat of August, a month of legendary proportions in baseball, which only the most fit survive. Finally the colorful spectacle of the World Series arrived in early October. In the winter, the game moved off the field to the warmth of the hot stove league. Just as there was a kind of flow to every baseball game, there was this flow for an entire season coinciding with the cycle of nature. In the process the periodic renewal, with a flush of hope and optimism. . . . suggested the particularly American approach to time and history.... The cry of "Wait till next year" and the irrationality of spring training optimism both serve to reaffirm the basic truth at the heart of America's outlook on life.2 Henry's UBA has many of these same features. Each season is played out and the records are carefully kept. Henry's history recounts the season and the games, following the players from rookie, to veteran, to old-timer, and finally to the grave. But Coover goes beyond this: Beyond each game, he sees another, and yet another, in endless and hopeless succession. He hits a ground ball to third, is thrown out. Or he beats the throw. What difference in the terror of eternity, does it make? He stares at the sky, beyond which is more sky, overwhelming in its enormity. He Paul Trench, is utterly absorbed in it, entirely disappears, is Paul Trench no longer, is nothing at all; so why does he even walk up there? Why does he swing: Why does he run? Why does he suffer when out and rejoice when safe? Why is it better to win than to lose? (171) Coover has hit something of great significance here and he takes it on further having one player tell another: "'I don't know if there's really a record-keeper up there or not, Paunch, but even if there weren't, I think we'd have to play the game as though there were'. Would we? Is that reason enough? Continuance for its own inscrutable sake" (172). Indeed it is! That is exactly the point ,it the game or i e. e pain of the strike of 1981 was one reminder of the importance of continuity. What Dallas Green called the "split-fuckin-season," only served to reinforce the need of "continuance for its own inscrutable sake." Coover also goes into the heart of each game, the games within the games. H lets you see Damon Rutherford, cool, detached, and perfect on the mound. He makes you fee the tension mount inning by inning, pitch by pitch, as Rutherford rolls to his perfect game. Even more impressive are the game fragments which appear as Henry plays out a season, or the recollection of games and players as Henry's mind is dominated more and more by the happenings of the UBA, and he slowly slips away into his own creation. The power of Coover's writing lends credibility to the power of the UBA over Henry's mind. It almost seems logical when Henry finally disappears inside the UBA, its rituals and its history. It is also a bit frightening. W.P. Kinsella in his introduction to The Thrill of the Grass writes, "it is the timelessness of baseball which makes it more conducive to magical happenings than any other sport."3 The magic runs through the UBA. It is also true that both baseball and history, while marching thro time, assume the timeless, seeking to transcend time, to escape the boundaries imposed by such a mundane human construct. There is within this novel and within Henry's games the sense that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts, and more important that the whole is essential to the parts. The import context is overwhelming-the crowd, the sun, the stadium, the gr grass, the sky, and the endless succession of games. Who is J. Henry Waugh? In his "normal" life he is an accountant, but in his baseball life he is among other thins a historian. He keeps the records and writes the histories. w y. e seeks continuity and meaning within the historical record, meaning which transcends the humd rum world of time and account books. He is the historian endlessly searching for the confluence of time and eternity. The only differences between Henry and other historians are the nature of his evidence, which seems less real than that of the historian, and the fact that Henry gets lost in his evidence. Henry is fascinated by baseball's history and continuity, and the league he creates is permeated by those qualities. Base a is ritual, transcending time and reenacting the patterns of nature, the cycles of birth-life-death, be it UBA or MLB. Beyond this Coover captures other intriguing aspects of the game. Henry tries to explain to his friend Lou what it is about baseball that captivates him: The crowds, for example, I felt like I was part of something there, you know, like in church, except it was more real than any church, and I joined in the score-keeping, the hollering, the eating of hot dogs and drinking of Cokes and beer, and for a while I even had the funny idea that ball stadiums and not European churches were the real American holy places. (121) But ultimately, confessed Henry, the games themselves were boring, and it was only later when he looked over the scorecards from the games that he found them coming to life. In the end we found he didn't need the games, the scorecards were enough. (Was he a SABR member?) What went on in the mind was more important than what went on in the field. This of course is no surprise to those who still find that in many ways a baseball game on the radio is much more satisfying than a game on television. The game in the mind, and of the mind - not a bad description of baseball, or as Coover writes - "He wants to quit ... But what does he mean 'quit'? The game? Life? Could you separate them?" (171). Henry had over the years invented numerous other games-basketball, horseracing, war games, card games. He even invented a twenty-four board monopoly game played by an unlimited number of players involving multinationals and international power politics. But he always came back to baseball. Why? ... the records, the statistics, the peculiar balances between individual and team, offense and defense, strategy and luck, accident and pattern, power and intelligence. And no other activity in the world had so precise and comprehensive a history, so specific an ethic, and at the same time, strange as it may have seemed, so much ultimate mystery. (38) And mystery there is, with part of it coming from the names. To Henry the naming of his players was of utmost significance. Names must be chosen "that could bear the whole weight of perpetuity. Brock Rutherford was a name like that; Horace (n) Zifferblat wasn't.... Strange. But name a man and you make him what he is” (39). It is in fact a funny thing about names, and nicknames, in baseball. They often do seem just right: Nolan Ryan, Eric Davis, Damon Berryhill, Vic Power, Babe Ruth, Jimmy Foxx, Ty Cobb, Dizzy Dean, Dazzy Vance. Or try some of Henry's names: Damon Rutherford, Witness York, Hatrack Hines, Jock Casey, Goodman James. But Richard Crepeau? You just know he couldn't hit the curveball with a name like that. Kevin Kerrane in Dollar Sign On the Muscle tells us that the scouts look for players with the "good face." Perhaps they should just run down a list of names. Coover makes the observation that baseball contains the possibility for perfection only for the pitcher. Henry notes this while recording the statistics from Damon Rutherford's perfect game with all those zeroes. The only thing comparable to a zero, the absence of number, is infinity, and infinity is not available to the batter. He cannot hit an infinite number of home runs. Furthermore baseball has other peculiarities in this area. The perfect game offers an occasional glimpse at perfection, but for the batter the rule is failure. Fail 7 of 10 times and you area good hitter; fail 3 of 5 times and you are a great hitter. The margins of this game are very small. Here again one finds a large part of the beauty and delicate balance of baseball revealed in Henry's mental meanderings. Part of that wonderful balance is described by Lois Gordon, who points out that baseball is a game of "tremendous excitement, it pits control against chance; each and every move offers its players potential great accomplishment, public adulation, and even immortality."4 Not to mention their opposites. Closely related to this is Henry 's fascination with numbers which are another of the mysteries in the game. ... it seemed somehow central to the game to maintain the balance provided by any power of two. To say a team finished in "first division" implied the possibility of further divisions, but a five-team division couldn't be further divided. Moreover, seven -the number of opponents each team now had-was central to baseball. Of course, nine, as the square of three, was also important: nine innings, nine players, three strikes each for three batters each inning, and so on, but even in the majors there were complaints about ten-team leagues, and back earlier in the century, when they'd tried to promote a nine-game World Series in place of the traditional best-out-of-seven, the idea had failed to catch on. Maybe it all went back to the days when games were decided, not by the best score in nine innings, but by the first team to score twenty-one runs ... three times seven. Now there were seven fielders, three in the outfield and four in the infield, plus the isolated genius on the mound and the team playmaker and unifier behind the plate; seven pitches, three strikes and four balls; three basic activities - pitching, hitting, and fielding - performed around four bases.... (148) Or later: Numerology. Lot of revealing work in that field lately. Made you wonder about a lot of things. Like the idea Damon was killed in Game 49: seven times seven. Third inning. Unbelievable. Or like that guy who's discovered that the whole damn structure from the inning organization up and double entry bookkeeping are virtually identical; just multiply it by twenty-one, the guy claims, and you've got it all. Grim idea. (158) Lois Gordon and others have discussed the religious symbolism of the numbers both in baseball, and in Henry's rolling of the dice. This also fits well with Coover's portrayal of the game as religious ritual, especially in the final chapter, when the events surrounding the death of Damon Rutherford are reenacted in the Parable of the Duel and the Great Atonement Legend on Damonsday, with its implication of ritualistic human sacrifice. These events take place one hundred seasons after Damon's Death, and the players have learned of these events from their catechisms. Along with this use of the numerology of the game and its religious overtones, Coover makes marvelous use of the language of baseball. As noted earlier, his game descriptions are vivid and evocative. But beyond that he takes the language of baseball into other settings. His use of baseball language to describe sexual intercourse is certainly not new, but Coover's particular descriptions of Henry's romp with Hettie, the B-girl, are beyond the ordinary: Oh, come on, come on, Henry, here, come on home! Yes, and they're pulling for him, Hettie, and he rounds second, he's trying to stretch it to third, but I don't know, it's still a long ways to the plate, no, he just can't make it, not this time, and the second baseman, he's got the ball, and he's gonna-No, no, Igot it, Henry, 1 got it! come on! come on! keep it up! Behind his butt, she clapped her cold soles to cheer him on, Yes, he's pushing toward third now, yes! and he's picking up, yes, that's it! he's hard to stop now, he's churning, he's pouring it on, and he's around third! on his way home! but they've got him in a hotbox! wow! third to catch! back to third! ha! to catch! to pitch! catch! pitch! catch! pitch! Home. Henry, home! And here he comes, Hettie! He's past'em! past'em! past'em! he's bolting for home, Spurting past, sliding in-POW! Oh, pow, Henry! pow pow pow pow POW! They laughed softly, hysterically, flowing together. She let go her grip on theball. He slipped off, unmingling their sweat. Oh, that's a game, Henry! That's really a great old game! (31) Coover also explores the linkage between baseball and the American pastoral, tying it to country music and noting the ironies: "Funny thing about both country music and baseball with its 'village greens;' they weren't really country, not since they got their new names anyway, but urban" (32). Henry writes country music ballads about the game, the players, and the legends not unlike, but considerably more colorful than, Terry Cashman's minor growth industry, "Talkin Baseball." The most colorful of these ballads is "Long Lew and Fanny," which recounts in bawdy and colorful verse the story of how Fanny McCaffree lost her virginity to Lew Lydel. Henry sees baseball, the whole atmosphere of the game, as "Formulas for energy configurations where city boys come to see their country origins dramatized, some old lost fabric of unity... " (121). Coover allows pastoralism to run amuck in Henry’s mind. Oh, Cooperstown and Abner Doubleday, no wonder you will not give way to the so-called facts! Near the end of the novel Henry, while looking over his records and history of the UBA, was struck by the optimism with which he had written in the early years of the league. Over the years he had changed. He could no longer write with optimism and jauntiness, but he was still caught up in the action, the games, the rituals and the history. These were the attractions of the game that ultimately enveloped J. Henry Waugh, and which Coover used so skillfully. They also explain why, after all the scandals and money grubbing, the agents and lawyers, the strikes and the lockouts, and afterall the innocence of youth has passed, baseball still holds a tight grip on all of those who, along with J. Henry Waugh, have felt the mysteries. Notes 1. John Steinbeck, "Then My Arm Glasses Up," Sports Illustrated, 23 (December 20,1965), p.100 2. Richard Crepeau, Baseball: American's Diamond Mind, Orlando, Florida: University Presses of Florida, 1980, pp. 64-65. 3. W. P. Kinsella, The Thrill of the Crass. New York; Penguin Books, 1984, p. xii. 4. Lois Cordon, Robert Coover: The Universal Fictionmaking Process, Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 1983, p. 40.