Nike: Making and Mastering Markets

advertisement

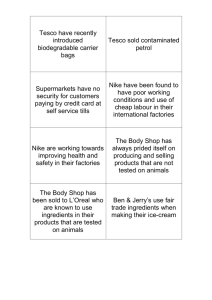

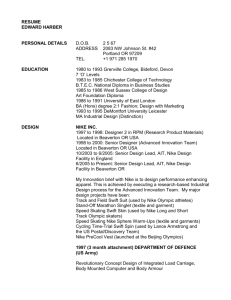

Nike: Making and Mastering Markets What do you call a company of thinkers? It’s not a joke, nor a Buddhist riddle. Rather, it’s a conundrum about one of the most successful companies in the United States. It’s known worldwide for its products, none of which it actually makes. This begs two questions: If you don’t make anything, what do you actually do? If you outsource everything, what’s left? A whole lot of brand recognition, that’s what. Nike, ever denoted by its trademark Swoosh, is still among the most recognized brands in the world and an industry leader in the $57 billion U.S. sports footwear and apparel market. And with 33 percent market share, it dominates the global athletic shoe market. Since captivating the shoe-buying public in the early 1980s with indomitable spokesperson Michael Jordan, Nike continues to outpace the athletic shoe competition while branding an ever-widening universe of sports equipment, apparel, and paraphernalia. The omnipresent Swoosh is seen everywhere from bumper stickers to sunglasses to high school sports uniforms. Not long after the introduction of Air Jordans, the first strains of the “Just Do It” ad campaign sealed Nike’s reputation as a megabrand, and the Nike image made the strategic shift from simply representing products to embodying love of sport, discipline, ambition, practice, and all other desirable traits of athleticism. (It was also among the first 1 in a long-line of brands to latch on to the strategy of representing the freedom of selfexpression.) Advertising has played no small part in Nike’s continued success. In the United States alone, Nike spent $85 million on advertising in 2005, with a combined total of $213 million in measured media in 2004, according to TNS Media Intelligence. (In comparison, Adidas spent $47 million and Reebok spent $26 million.) Portland ad agency Wieden + Kennedy has been instrumental in creating and perpetuating Nike’s image, so much so that the agency has a large division in-house at Nike headquarters. This intimate relationship allows creatives to focus solely on Nike work, and it gives them unparalleled access to executives, researchers, and anyone else who might provide the next inspiration for promotional greatness. And though Nike took the clever step of keeping its ad agency nestled close to home, it has relied on outsourcing so many of its other non-executive responsibilities as a means to reduce overhead. It could be argued that Nike, recognizing that its core competency lies in the design—and not the manufacturing—of shoes, was wise to transfer production overseas. 2 What’s Left, Then? But Nike has taken outsourcing to a new level, barely producing any of its products in its own factories. All its shoes, for instance, are made by subcontractors. And though this allocation of production hasn’t hurt the quality of the shoes at all, it has challenged Nike’s reputation among fair-trade critics. After initial allegations of sweatshop labor surfaced at Nike-sponsored factories, the company tried to reach out and reason with its more moderate critics. But this approach failed, and Nike found itself in the unenviable position of trying to defend its outsourcing practices while defending the location of its favored production shops from the competition. So in a bold move designed to make converts of critics, Nike recently announced that it will post information on its Web site about all the approximately 750 factories it uses to make shoes, apparel, and other sporting goods. It released the data alongside a comprehensive new corporate responsibility report summarizing the environmental and labor situation of its contract factories. “This is a significant step that will blow away the myth that companies can’t release their factory names because it’s proprietary information,” said Charles Kernaghan, executive director of the National Labor Committee, a New York-based anti-sweatshop group that has been no friend to Nike over the years. “If Nike can do it, so can Wal-Mart and all the rest.” Jordan Isn’t Forever Knowing that shoe sales alone wouldn’t be enough to sustain continued growth, Nike made the lateral move to learn more about its customers’ involvement in sports and what 3 needs it might be able to fill. Banking on the star power of the Swoosh, Nike has successfully branded apparel, sporting goods, sunglasses, and even an MP3 player made by Philips. Like many large companies who have found themselves at odds with the possible limitations of their brands, Nike realized that it would have to master the onetwo punch of identifying new needs and supplying creative and desirable solutions. To this end, Nike has branched into previously unexplored merchandising arenas. Assuming the company’s original name from longtime CEO Phil Knight, it quietly launched the Blue Ribbon Sports line of urban-themed apparel. Sold only at high-end shops like Fred Segal and Barney’s, the line seeks to fill a niche only recently discovered by Adidas/Stella McCartney collaboration. In fitting with the times, Nike’s head design honcho, John R. Hoke III, is encouraging his designers to develop environmentally sustainable designs. This may come as a surprise to anyone who’s ever thought about much foam and plastic goes into the average Nike sneaker, but a corporate-wide mission called “Considered” has designers rethinking the toxic materials used to put the spring in millions of steps. “I’m very passionate about this idea,” Hoke said. “We are going to challenge ourselves to think a little bit differently about the way we create products.” And never one to shy away from self-promotion, Nike found a buzz-worthy way to bring customers—and thousands of New Yorkers—closer to the design process. The Nike iD project allows customers to intimately customize a pair of shoes, down to their choice of labels on the tongues. In a promotion designed by interactive agency R/GA, Nike offered customers a telephone number to call to walk then through the iD design process. As they made their choices of leather and lace colors, graphics depicting their 4 evolving sneakers were displayed on the Reuters sign twentythree stories above Times Square. It’s an ingenious promotion, and as one marketing type observed, “When a shoe that you’ve designed arrives at your door, it changes the way you feel about Nike.” Nipping at Nike’s Heels But despite its success and market retention, it hasn’t been all roses for Nike recently. Feeling the need to step down, Phil Knight handed the reins to Bill Perez, former CEO of S. C. Johnson and Sons, who became the first outsider recruited for the executive tier since Nike’s founding in 1968. But after barely a year on the job, Knight, who stayed close as chairman of the board, decided Perez couldn’t “get his arms around the company.” Citing numerous other conflicts, Knight accepted Perez’s resignation and promoted Mark Parker, a twenty-seven-year veteran who was co-president of the Nike brand, as a replacement. Pressures are mounting from outside its Beaverton, Oregon, headquarters as well. German rival Adidas drew a few strides closer to Nike when it purchased Reebok in 5 August 2005 for approximately $3.8 billion. Joining forces will collectively help the brands negotiate shelf space and other sales issues in American stores, as well as aid in price discussion with Asian manufacturers. With combined global sales of $12 billion in 2004, the new supergroup of shoes isn’t far from Nike’s $14 billion. According to Jon Hickey, senior vice president of sports and entertainment marketing for the ad agency Mullen, Nike has its “first real, legitimate threat since the ’80s. There’s no way either one would even approach Nike, much less overtake them, on their own,” he said. But now, “Nike has to respond. This new, combined entity has a chance to make a run. Now, it’s game on.” But when faced with a challenge, Nike simply knocks its bat against its cleats and steps up to the plate. “Our focus is on growing our own business,” said Nike spokesman Alan Marks. “Of course we’re in a competitive business, but we win by staying focused on our strategies and our consumers. And from that perspective nothing has changed.” But Who Doesn’t Have a Closet Full of Sneakers? Big brands die hard, and Nike enthusiasts are still rabid over their favorite kicks. For many fans, old Nikes are more than keepsakes from childhood; they can sometimes be rare collectables, even art. Launched in 1982, the Air Force 1 line is still the definition of success for Nike. It earned an estimated $1 billion in 2005, with profit margins of 70 percent, according to analysts. And Nike has managed to perpetuate the design without alienating consecutive generations of shoe-hungry teens. 6 But at the end of the day, it’s kept hot by an age-old strategy: limited supply. Every two months, Nike ships roughly 350,000 to 500,000 pairs nationwide of a slightly modified version of the AF1—camouflaged, or styled for an upcoming holiday or event—with each participating store stocking only 25 to 30 pairs. Retailers are encouraged—at the risk of having later pairs withheld—not to discount new AF1 releases. Ever quick to articulate their desires, shoe enthusiasts even petition Nike to massproduce models never released to the market. Al Cabino, a young sneaker enthusiast from Montreal, adores the moonboot Nikes worn by Michael J. Fox in Back to the Future II. In fact, he so adores them that he started an online petition to get Nike to produce them. “They’re the most mythical sneakers in film history,” he rhapsodized. So far, Cabino has collected more than 4,300 signatures from more than thirty countries. “It’s a nostalgia thing,” affirmed Chris Vidal, one of the employees at Flight Club, a sneaker consignment shop in New York’s Greenwich Village. “People want these sneakers as a keepsake.” 7 New Balance: No Heroes, Just Sneakers Sometimes there are advantages to being the odd one out. In an era in which outsourcing is a dirty word to every one except manufacturers, New Balance seems to have done what so many of its competitors couldn’t: maintain quality and price control while keeping much of its manufacturing in the United States. Taking the Quiet Approach With a small ad budget and no celebrity endorsements or big-name sponsorships, New Balance has captured a sizeable portion of the U.S. sneaker market: Between the mid-1990s and 2002, New Balance’s growth averaged 25 percent annually. From 1999 to 2001, the company’s market share grew from 3 percent to 10 percent. Compare this to Nike, which went from 48 percent to 43 percent, and Reebok, 15 percent to 12 percent, over the same period. For 2004, the company garnered $1.5 billion in worldwide sales. Most of its manufacturing operations are centered in northeastern states like Maine and Massachusetts. The company is adamant about preserving jobs in the United States, thereby distinguishing it from its otherwise more successful counterparts. Scour its Web site to your heart’s content, but you won’t find any mention by New Balance of any professional athletes promoting its sneakers. The “Everyday Athletes” 8 campaign highlights the accomplishments of average folk who break a sweat simply for their love of sport. The strategy departs from the competition’s emphasis on celebrity or athletic superstars to impress consumers and earn brand allegiance. In an age in which hiphop stars are the latest icons to cross over to product endorsement, many New Balance wearers find the company’s emphasis on run-of-the-mill athletes refreshing. Feet tend to find New Balance shoes refreshing as well. The company offers each of its shoes in at least five widths, as opposed to the industry average of three. Knowing that satisfied wearers tend to become repeat customers, New Balance has proven that sometimes it pays to be just a little different. 9