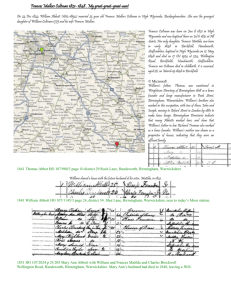

draft report - Be Birmingham

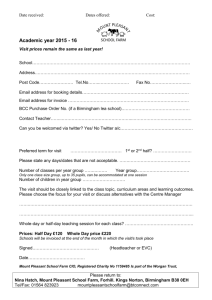

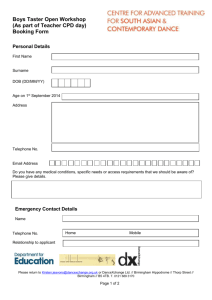

advertisement