Imperialism, Progressive Era, & WWI Classnotes

advertisement

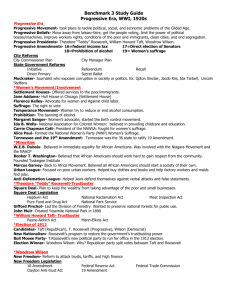

Story of U.S. Imperialism or “God Directs Us, Perhaps It Will Pay” 1. In the late 1800s the major powers of the world (Britain, France, Russia, Germany, the Dutch, and Japan) were busily carving up Africa and Asia. The act of taking colonies and creating an empire is called imperialism. There were several motivations for taking colonies, but it basically boils down to power and money. More colonies equals more resources, places to sell goods, and cheap labor. 2. To be an imperial power required a large navy. American historian Alfred Mahan pointed out in his 1890 book The Influence of Sea Power Upon History that all the great empires throughout history (like the Roman Empire) had build large navies. Mahan’s book was widely read by world leaders (including our own Teddy Roosevelt) and inspired a naval arms race. That is, each of the world powers competed to create the largest and most powerful navy. Of course, once on the ground in a colony, a country needed a strong army to control the natives— thus the Europeans raced to build up their armies as well. This would all come to a bad end during WWI. 3. By about 1890 several factors contributed to the U.S. joining the race for colonies. a. The U.S. was becoming one of the world’s economic powers. In fact, the U.S. was producing so many products that we didn’t have enough people to buy them all. By taking colonies, the U.S. would have more places to sell its products. In addition, the U.S. could secure important resources from colonies. b. Looking at the European powers, the U.S. felt it was being left behind. The U.S. felt it had to join the race for empire to “keep up with the neighbors.” c. Another factor was that America’s frontier was declared closed in 1890. After 300 years of having a frontier, American’s had come to believe that it was the source of freedom and opportunity. This had been pointed out by Frederick Jackson Turner in a book titled The Significance of the Frontier in Amercian History (1893).Without a frontier, it was thought, America would decay. But by taking colonies, a new frontier could be opened overseas. d. Finally, Americans had come to believe (as had the Europeans) in an odd notion called the “white man’s burden.” American’s believed that their culture (including Christianity, democracy, and a capitalist economy) was superior. They felt that they had an obligation to teach it to the “lesser” peoples of the world. Of course, this was a very racist notion, one which we have hopefully outgrown. 4. About this time an opportunity presented itself for the U.S. to join the race for empire. Spain’s 400-year-old empire was crumbling. In an attempt to hang on to its few remaining colonies (Cuba, Puerto Rico, Samoa, Guam, and the Philippines) the Spanish were treating the native residents very poorly, especially in Cuba. The U.S. warned Spain to treat its colonists better, but the Spanish told the U.S. to mind its own business. As tensions grew, an American naval ship the Maine blew up in Havana Harbor. 5. The “Yellow Press” (newspapers that made money by sensationalizing the news, so named for their colored comic strips) in the U.S. immediately blamed the Spanish and called for war. It was later learned that the ship had not been attacked but had exploded from inside. Many Americans were excited for war, including Teddy Roosevelt, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy. He actually ordered the American Navy to move into position for war. 6. President McKinley soon caved into the pressure and war was declared. One of the first to sign up for the army was Teddy Roosevelt. He fought bravely in Cuba leading his Rough Riders up San Juan Hill. Overall, Spain didn’t present much opposition and in a few months the U.S. found itself in possession of an empire, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, American Samoa, and Guam. During the war the U.S. also annexed Hawaii. 7. Many Americans weren’t so sure that becoming a colonial power was such a good idea. These people were called anti-imperialists and they said America should be promoting liberty and democracy, not colonization. In fact, during the war the U.S. passed the Teller Amendment. This said that the U.S. would only fight to free Cuba, not to keep it as a colony. Once the war was over, the U.S. did indeed free Cuba, but with strings attached—this was called the Platt Amendment. This act insisted that the Cuban constitution be written to allow the U.S. to intervene in Cuba in case of disorder, failure to pay debts, or if Cuban independence was threatened. We also kept a military base at Guantanamo Bay, which we still hold. 8. The Supreme Court later ruled in the Insular Cases (1901) that the U.S. Constitution didn’t apply in non-U.S. territory. Since Guantanamo was technically part of Cuba, the Constitution wasn’t in effect there. This is why the U.S. government to this day uses it for a prison camp: detainees there do not have access to the usual rights of a fair and speedy trial, etc. 9. Meanwhile, back in the Philippines, Admiral Dewey easily defeated the Spanish fleet. But taking a colony is always easier than keeping it. Almost immediately an insurrection against U.S. control was launched by Emilio Aguinaldo. He and his guerilla fighters waged a bitter war for two years before being defeated. In this conflict the U.S. used cruel tactics, including “water boarding” and other torture. 10. During this long war, McKinley wondered if the U.S. was doing the right thing. Supposedly he got down on his knees and prayed about what to do. He decided that we should help the Filipinos to become civilized (that is democratic, capitalist, and Christian)—but that we should keep them as a colony too. A smart-alecky historian joked that McKinley had prayed to God and decided that “God directs us, perhaps it will pay.” That is, we will do what is right, and we’ll make some money while we’re at it. If you think of U.S. history, this is often the case; think of Iraq: we liberated the Iraqis, but of course now have access to Iraqi oil. We often stand up for liberty (which is good), but often we aim to make a little money while we are at it. 11. In 1899 as the U.S. was becoming an imperial power, China was in danger of being carved up into little colonies. If this happened, the U.S. would not be able to sell its goods there. To keep China open to all trade, the U.S. issued the Open Door Note and pressured the other powers, including Japan, to accept this idea. The others agreed, but only begrudgingly (that is, they didn’t like it). 12. In 1900 a group of Chinese patriots rose up in the Boxer Rebellion and attacked the imperialists, including missionaries and businessmen. A multi-national force, including troops from the U.S. soon put down the rebellion. The Chinese were forced to pay reparations (a fine paid by the loser of a war). The U.S. later gave back their share; in turn the Chinese used the returned money to send students to the U.S. for college; and the U.S. and China became allies. Thus another example doing the right thing, but with some profit too. 13. Now that the U.S. had an empire—in both the Pacific and the Atlantic—Teddy Roosevelt (now president) decided we needed a quicker way of getting our navy between oceans. He approached the Colombians in 1903 (who at that time owned the Isthmus of Panama) about selling an 8-mile wide strip for a canal. They flatly turned him down. Not to be denied, he encouraged the Panamanians to declare their independence from Colombia and provided U.S. gun boats to back them up. The newly independent Panamanians soon sold us the canal zone— this time 10 miles wide. Soon the U.S. was digging the canal and had it finished a few years later. 14. Ever since the Monroe Doctrine was issued in 1820, the U.S. had insisted that there would be no more colonization by Europeans in the Western Hemisphere (that is North, South, or Central America). Now that America had colonies and a canal in Latin America, the U.S. was all the more interested in keeping the Europeans out. The problem was that Caribbean island nations would borrow money from the Europeans and get in debt. The Europeans would threaten to invade these countries to force them to pay back their debts. The U.S. felt that this would start a new era of colonization. So Teddy Roosevelt issued the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. This said that the U.S. would invade Latin American countries to force debt payments or to reestablish order so that European countries wouldn’t have the excuse to do so. That is, we invaded so that others wouldn’t. 15. Back to the Pacific. Now that the U.S. controlled the Philippines, Samoa, Guam, and Hawaii, we had become a Pacific power. The other new kid on the empire block was Japan. Tension soon developed between the U.S. and the Japanese as to who would be the top-dog in the Pacific. 16. Tensions flared in 1907 when California passed laws that discriminated against Japanese immigrants (for example, their kids were prevented from attending public schools). The Japanese government resented this poor treatement. Teddy Roosevelt secretly worked out a deal: if the Japanese would prevent further immigration to the U.S., the U.S. would treat those already here fairly. This was called the “Gentleman’s Agreement.” 17. After this secret deal Teddy Roosevelt was worried that Japanese would think he was weak. So he sent American naval ships (the “Great White Fleet”—the ships were painted white) on a “good will” tour around the world—first stop Japan. The Japanese welcomed our ships, but got the message: don’t mess with the U.S. Of course they resented this and eventually attacked the U.S. at Pearl Harbor in 1941, kicking off WWII in the Pacific. However, that was still 30 years in the future. In 1908 a peace of sorts was established between the U.S. and Japan with the Root-Takahira Agreement. Both sides agreed to not meddle with the other’s colonies—at least for now. Story of the Progressive Era 1. The Progressive Era (1900-1920) was a period of reform during which many of the worst problems of the Gilded Age were addressed. The problem was that the old laissez faire system of no government regulation, which had worked so well to ensure freedom prior to industrialization, was now outdated. An example: before the invention of the Bessemer process allowing mass-produced steel and the invention of the electric elevator, buildings over 5 stories were not practical. When a fire broke out in one of these old-style brick buildings, fire ladders or hand-held nets were adequate for helping people trapped in the upper stories to escape. No complicated set of government fire codes was necessary for safety. During the Gilded Age, modern buildings of 10 and 20-plus stories were built, but fire codes were not updated, often with tragic consequences. In 1912, for example, 141 young immigrant girls died in a horrible fire in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in NY City, many of whom leaped from the 9th and 10th floors to their death. After the fire, the city fire code was reformed (or fixed) to reflect modern needs. Many other reforms were adopted during these two decades. 2. Much of the drive for reform during the Progressive Era came from the middle class and the “old money” class (people whose families had been rich for at least a few generations). They worried that the new rich (men like John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan) were headed for a violent showdown with the beaten down working class. The workers were indeed looking to the ideas of socialism, and even it’s more violent cousin, anarchism. They also recognized that the political system was corrupt, that products were unsafe, and that the working poor were getting a raw deal. 3. The middle class and “old-money” types were made aware of the growing crisis by a new class of writers whom Teddy Roosevelt named muckrakers. These writers investigated and described in books, newspapers, and magazines the problems that society faced. Once aware, the middle class and old-money types pushed for reforms (that is to fix the problems). Some examples: a. Jacob Riis, How the Other Half Lives (1890) – exposed the terrible living conditions in the tenements in New York using flash photography. b. John Spargo, Bitter Cry of the Children ( ) – Exposed the evils of child labor and malnutrition. c. Lincoln Steffens, Shame of the Cities (1904) – Exposed the corrupt way the major cities were controlled by political machines. d. Ida Tarbell, Standard Oil, () – Exposed John D. Rockefeller’s monopoly and cruel bullying of the oil industry. e. Frank Norris, The Octopus (1901) – Exposed how the Southern Pacific RR corrupted and controlled the political system in California at the expense of regular passengers and customers. f. Upton Sinclair, The Jungle (1906) – Exposed the terrible working conditions in the meat packing plants of Chicago and the slums surrounding the plants; also exposed the unsanitary conditions in the meat packing plants and the unhealthy products they produced. 4. Progressive reformers felt that the old unregulated system of laissez faire—where the government took no active role in the affairs of society—no longer worked in the modern world. As life became more complicated in the modern era of industry and cities, they felt that the government needed to take an active role in addressing problems. They believed that the government should hire experts to design solutions. They still supported private enterprise (capitalism), but thought it should be regulated. They were optimistic that government could solve the worst problems of the day. 5. Often dramatic events like the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire (1911) created an outcry for reform that brought about significant new laws and regulation (reform). 6. Many of the working class felt these changes didn’t go far enough; they supported socialism— the government take over of industry and an end to private ownership. Some extreme (radical) socialists decided that society could never be fixed. They joined socialistic communes (several dozen of these located in the Seattle Area); these idealistic experiments in communal living did not last very long. 7. Progressive reforms—that is, new laws to address the problems of the Gilded Age—occurred at all levels of government. For example, the federal (national) government passed laws to improve product safety; state governments passed laws to control the abuse of alcohol; and city governments passed laws to end the corruption of political machines. 8. One of the first significant progressive reformers was Teddy Roosevelt (TR). TR became president following the McKinley assassination. One of TR’s first actions was to take on the monopolistic trusts. TR promised the American people a “Square Deal.” By this he meant that he would treat all classes of Americans fairly. TR first demonstrated his philosophy during the 1902 Coal Strike. In the past, the government had always taken the side of the corporations during strikes. TR reversed this by trying to get both sides to negotiate. When the mine owners refused to talk, TR threatened to use the U.S. Army to reopen the mines. The mine owners at this point backed down and agreed to a 9-hour day and a 10% pay increase. However, they still refused to recognize the United Mine Workers’ Union. 9. TR was not opposed to big corporations. He just thought that they should be regulated and under control of an even more powerful government. One main area of American life which corporations dominated was transportation—namely the railroads. If you wanted to travel or needed to ship goods, you had little choice in many cities other than a railroad. Since most cities had only one railroad, the railroad corporations could charge virtually any price they chose. TR pushed Congress to pass several laws to curb the worst abuses to the railroads. He also sued J.P. Morgan’s Northern Securities trust (a monopoly of the northern railroads (including the two that came through Spokane). TR broke up this monopoly and 42 others to ensure that corporations would compete with one another and to show that the government was in charge—not the trusts. 10. TR also created a new cabinet position in 1903—the Department of Commerce and Labor—to oversee fair business practices and the fair treatment of workers. 11. Along with curbing (or controlling) trusts, TR sought to ensure that food and medicines were safe. After reading muckraking accounts of the food and patent medicine industries, TR pushed Congress to pass in 1906 the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act (which in the 1920s led to the FDA). 12. TR’s last area of reform was conservation. By 1900 half of America’s forests had been chopped down. TR believed that wild places were important places for physical and spiritual renewal. He set about creating dozens of national forests, monuments, and wildlife refuges, eventually setting aside some 230 million acres of land. He also created the Forest Service to manage these acres. It should be noted that TR was a conservationist, not a preservationist. Conservationists believe that forests should be protected, but also used in a careful manner for hunting and recreation as well as logging and mining. Preservationists wanted the land to be left virtually untouched by the hand of man. 13. After TR’s second term in office he hand-picked William Howard Taft to run for president in 1908. TR felt that Taft would carry on his Progressive policies. Taft actually broke up more trusts than TR, but he and TR had a falling out over forest conservation (Taft was not as willing to protect wild lands as TR). Also, Taft had supported the passage of a very high tariff (a tax on imported goods) which TR felt unfairly benefited corporations at the expense of common folks. 14. In 1912, TR formed a new party called the Progressive Party and ran against Taft (the Republican) and a new guy on the block, Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat. Wilson also believed in progressive reform, but from a different angle. Since TR and Taft split the Republican vote, Wilson won the presidency (only the second Democrat to be elected since the Civil War). 15. Wilson’s progressive philosophy was called New Freedom. Unlike TR, he believed that large corporations were inherently bad and should be broken up into many competing companies. Wilson pushed Congress to pass many important reforms, including: lower tariffs (and thus lower prices on goods for common folks); The Federal Reserve Act (reformed banking to make it more secure); and additional regulation of trusts through the Clayton Anti-Trust Act and the Federal Trade Commission. 16. Unfortunately, one area in which Wilson was not very progressive was race and segregation. Being from the South (Virginia), he had grown up with segregation. Once in the White House (that is, once president), he undid what little progress TR had started in this area and resegregated various government jobs. 17. It would not be accurate to think that all—or even most--Progressive Era reforms were due to the actions of the TR, Taft, and Wilson. Often problems were attacked by city, state, and federal governments all at once. A good example of this was the problem of corruption in politics. To try to end corruption of the Federal (national) Senate, the 17th Amendment to the Constitution was added making senators directly elected by the people of their states (instead of by the easily bribed state legislatures). States in the west adopted initiative and recall laws. These allowed citizens to sign petitions to create new laws or remove from office corrupt elected officials. Also, most states adopted the Australian (or secret) ballot which allowed voters to cast their ballots privately. Finally, many cities changed their form of government. Most dropped the easily corrupted strong-mayor systems for city manager or city commission forms of government. The city manager system took the power out of the hands of one mayor and put it in the hands of an expert manager; the commission form of city government divided up the mayor’s job into several positions held by commissioners, each in charge of a different aspect of the city (for example, commissioner of public works [things like streets and sewers]). Spokane is an example of a city that dropped the strong-mayor system and adopted the commission system. 18. Moral reform was another area that saw the involvement of multiple layers of government. Progressive reformers thought that they could better society by passing laws which would improve behavior, or morals. Thus many states passed “local option” laws to allow cities to decide for themselves if they wanted to be “dry” (prohibit alcohol) or “wet.” States and cities also passed temperance (or “blue”) laws to restrict the use and sale of alcohol (but not out right prohibition). Finally the Federal government banned alcohol outright with the 18th Amendment to the Constitution in 1919. Another area of moral reform was the city beautification movement. Many cities created parks and planted trees (think of Manito and Corbin Parks) in order to create a pleasant environment. Progressives believed that one’s environment shaped a person: nice environment equaled nice people. 19. Finally, local, state, and federal government all dealt with the ill-treatment of workers and the conditions that they lived in. Cities passed building and fire codes for tenements and factories; some cities, like Toledo, Ohio, even created local welfare systems to care for the poor. States passed 10-hour work day laws and child labor laws. Worker compensation laws were passed by many states to provide for injured workers and their families; finally, the federal government created the Department of Labor to oversee how workers were treated on the job. 20. The government’s new regulatory role cost money. People had to be hired as inspectors, etc. At the same time, the government had reduced the tariff (thus reducing the collection of taxes). To raise more money to fund the government, the 16th Amendment to the Constitution was adopted, creating the income tax. 21. After World War One began in 1914 (with U.S. entry in 1917), most of the focus on reform within the U.S. ended. However, the war did give rise to a final chapter of the Progressive Era—the passage of prohibition (18th Amendment, 1919) and women’s suffrage (or the right of women to vote, granted by the 19th Amendment in 1920). Americans associated German culture with drinking beer and alcohol; thus it seemed patriotic to support banning alcohol. People who favored prohibition also felt that banning alcohol would free up grain for food for the soldiers. Americans also felt that they were fighting WWI to spread democracy in Europe; supporters of women’s suffrage argued that it was silly to deny democracy (the right to vote) to women in the U.S. while fighting in Europe to spread this idea. 22. After the war the 20-year Progressive Reform Era had run its course. Many American’s yearned for the quieter days before the reform period and war. Republican President Warren G. Harding (elected in 1920) referred to this as returning to “normalcy.” Unfortunately, many of the important reforms of the Progressive Era were lost or ignored as America returned to its laissez-faire roots during the 1920s. This eventually would lead to the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Story of The Great War (World War I) 1. As the 20th Century opened a dangerous mix of factors merged to create the most massive and senseless slaughter of humanity up to that point in history (unfortunately WWII would be even worse). 2. In the years leading up to the start of the war in August of 1914, the Europeans, Americans, and Japanese had been aggressively competing in a nationalist scramble for power in the age of imperialism. Taking and holding colonies required a powerful navy and army. The arms race that developed left Europe loaded and cocked, just ready for any spark to ignite the Continent in war. 3. As tensions grew, countries banded together to form alliances for protection. a. Central Powers: Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey. b. The Allies: France, Britain, Italy, Russia, and Japan (with the U.S. joining the Allies toward the end of the war). In general the Central Powers were controlled by kings and the Allies were democracies, with the glaring exception of Russia and Japan. The alliance system increased the likelihood of war. If one country was attacked, the others would all be quickly dragged into the fray. 4. Adding to the explosive situation was long-held resentments between the closely related kings and queens of Europe. This terrible war had the feel of a family feud. 5. The late 1800s and early 1900s was a romantic period of grand expeditions. Europeans and Americans risked their lives to travel by dogsled to the North and South Pole, to climb mountains, and explore the world. During these expeditions men pitted themselves against nature and if they made it home, had grand tales to tell. Combined with no photos, movies, or living memories of the horror of the Napoleonic wars of the early 1800s, Europeans were eager to embark on what they thought would be the grandest adventure of all: war. (Americans were a little less naïve—but not much—thanks to the terrible bloodshed of the Civil War in the 1860s.) 6. Finally, this was the first war fought after the invention of the Bessemer process—that is, the first war fought with mass produced weapons. The factories of Europe and the U.S. poured out an avalanche of deadly weaponry. Making matters worse, the tactics of the generals had not caught up with the technology. The generals thought if their men simply tried harder—that is, had more will than the enemy—that they would triumph. This simply didn’t work and resulted in millions of dead men machined gunned, gassed, and blow to pieces by high explosive artillery. 7. The spark that ignited the killing occurred when the future leader of Austria-Hungary and his wife were killed by Bosnian assassins with support from Serbia. When Austria-Hungary retaliated by attacking Serbia (encouraged by their ally Germany), Russia came to the aid of its ally Serbia, triggering a cascade of attacks by all of the major players: the war was on. 8. Germany—the major industrial power of the Central Powers—knew that it needed to act quickly to avoid a two-front war. German General Schlieffen developed a plan to deliver France a quick knock-out blow followed later by an attack on Russia. After driving deep into France (through neutral Belgium, which brought ally Britain into the war), the German advance on the Western Front was stopped by the advantage of the defense. Simply put, with modern weapons attacking in the open was almost impossible. However, the French were also unable to drive the Germans back and thus a stalemate developed on the Western Front. 9. Meanwhile, Russia attacked Germany and Austria-Hungary from the east and a similar stalemate developed on the Eastern Front. On both fronts, neither side was able to break through the other side’s trenches. Attacking across “no man’s land” against an enemy in a trench became impossible. Protected by barbed wire and using modern weapons (machine guns, gas, artillery, rifles, hand-grenades) the defense had a huge advantage. 10. The main role of the Japanese in the war was to block German shipping in the Pacific. They also used the war as an excuse to expand their colonies and influence in Asia, especially at the expense of China. 11. Back in Europe, from early 1916 into 1917 there were three major attempts on the Western Front to break the stalemate. Similar battles also occurred on the Eastern Front. a. In February 1916 German commander Alfred von Falkenhyn sought to crush the French will to resist at Verdun. Using a strategy of attrition (the goal was to wound or kill 3 or more French soldiers for every German casualty), the Germans only gained four miles in 10 months of fighting with a total for both sides of a million casualties. b. In July of 1916 British General Douglas Haig ordered a massive assault on the German line at the River Somme to the north of Verdunn. The British bombarded the German line for a week with high explosive artillery shells and thought they would be able to walk through the German line, but the Germans had survived in their dugouts. The British lost 60,000 men on the first day. Over the next several months 1.25 million men were wounded or killed on both sides as the British gained a paltry 8 miles of territory. c. Finally, in the winter of 1917-18 the British attempted another break through attack further to the north in Flanders at Passchendaele (sounds like “passion dale”). The battlefield turned into a sea of mud and no gain was made but another 650,000 men were killed or maimed. 12. Faced with what were obviously pointless battles and death, the troops began to refuse to fight (mutiny) in late 1917. In Russia, the rebelling troops actually overthrew the government, launching the Russian Revolution. 13. Throughout its history, the U.S. had attempted to remain isolated from European affairs. Sticking to this tradition during the first 3 years of the war the U.S. attempted to remain neutral. President Wilson encouraged Americans to remain neutral in “thought as well as deed.” But U.S. corporations sold millions of dollars of supplies/weapons to Britain and France. In addition, the Americans lent billions of dollars to the Allies so that they could buy U.S. weapons and supplies. The U.S. would have sold weapons to the Central Powers as well but the British navy blockaded German ports. By trading (and lending money) only one side, the Americans in effect were not acting in a neutral manner. 14. At the outset it wasn’t guaranteed that the U.S. would join the Allies. Many U.S. residents had German ancestors and sympathized with the Central Powers. But overall, the U.S. was more closely related to Britain through language, culture, democratic traditions, and trade and thus leaned toward the Allies. 15. German aggression further tilted the U.S. toward the Allies. If you think about it, the Germans were between a rock and a hard spot. If they let the “neutral” trade between the U.S. and the Allies continue they would lose, but if they sank American ships or British vessels with Americans on board, they would provoke the U.S. a. The Germans attempted to use U-Boats (submarines) to break the British blockade and sink ships carrying weapons. Inevitably they torpedoed ships with Americans on board. The Lusitania, for example, was sunk in 1915 with 118 Americans on board. In 1917 German UBoats sunk 430 “neutral” ships. b. After yet another a cargo ship the Sussex was sunk in March 1916, the U.S. warned that further attacks would lead to war. Germany promised in the “Sussex Pledge” that they would end the attacks. This meant that the decision regarding U.S. entry into the war was now in Germany’s hands. c. Making matters worse, in 1917 the British intercepted a secret German invitation to Mexico to join the Central Powers called the Zimmerman Note. Germany hoped that the U.S. would be too busy with Mexico to come to the aid of the Allies in Europe. Mexico wisely declined. 16. A final factor that helped bring the U.S. into WWI was Progressive Era Idealism. The U.S. had fixed many of its own Gilded Age problems with various reforms. Now Wilson proposed to fix Europe. He promised that this war would “make the world safe for democracy” and be a “war to end all wars.” In all Wilson laid out “Fourteen Points” that he hoped would give meaning to the bloodshed. This plan included promoting democratic governments, free trade (that is, end monopoly of the ocean), and preventing future wars through a League of Nations. 17. Once war was declared in early in April of1917, the U.S. found itself mostly unprepared for war. Although there had been a “preparedness movement,” including military training camps (1915), and a bigger military budget in 1916, the U.S. could only muster 120,000 soldiers, mostly in the navy). So few weapons were available, that recruits were sometimes trained w/ sticks. In fact, it took until the summer of 1918 to bring a large numbers of Americans into battle, and even then they often had to borrow artillery and other weapons from the French and British. 18. Although there was a lot of initial enthusiasm for the war, the fact that the U.S. had to implement a draft to fill out the ranks of the army indicated that not everyone was all that excited. To build support for the war Wilson created a “Committee on Public Information” headed by George Creel, a master of propaganda. The Committee splashed patriotic posters across the country and hired 75,000 “four-minute men” to whip up support with short patriotic speeches. 19. The U.S. desperately needed to organize its war effort, but a long tradition of laissez faire led to opposition to strong federal control. Still the federal government created various War Boards to provide central direction to the war economy. These included the War Industries Board, the War Labor Board, and the Food Administration. In addition, the federal government took control of the railroads for the duration of the war and passed a “work-or-fight” law to ensure that all able-bodied men lent a shoulder to the war effort. 20. To help pay for the war the government sold Liberty bonds and the income tax was raised. 21. To help ensure enough supplies for the troops, voluntary food and fuel rationing was encouraged; scrap metal drives were organized; and day-light savings was instituted. 22. Typical during wartime, Americans sought to distance themselves from all things German. Hamburgers were called “liberty sandwiches” and bratwursts/wieners became “hot dogs”; German language classes were dropped and German books were burned; people of German birth were attacked, and one was even lynched. 23. The war created social mobility for blacks and women. During the First Great Migration, 500,000 blacks move north to work, especially to NY City. Some 400,000 women entered the industrial work force, although almost all were forced to give up their jobs after the war. 24. Unfortunately there was a great deal of repression of civil liberties during the war. The Sedition and Espionage Acts made it illegal to criticize the government, the war effort, or the military. Socialist Eugene Debs was jailed for urging people to “resist militarism” and radical union leader “Big Bill” Haywood was jailed for encouraging workers to strike against the “capitalists’ war.” 25. Blacks also faced repression. Although their labor was desperately needed, the reality of discrimination remained. Blacks served in segregated units and were almost always assigned to non-combat labor duty. In fact, the most decorated black regiment—the “Harlem Hell Fighters”—fought not under the American flag but for the French. 26. American women and blacks pointed out the irony of fighting for democracy in Europe when they were denied full rights, including the vote. Under intense pressure from women suffragists, some of whom protested by chaining themselves to the Whitehouse fence and engaging in a hunger strike after being arrested, Wilson finally encouraged the states to ratify the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote. 27. The long campaign to ban alcohol finally succeeded during the war with the ratification of the 20th Amendment. The argument that pushed prohibition over the top was that the grain used for making alcohol would be better used for food for the troops. The fact that German culture was associated with beer contributed as well. 28. Getting back to the actual fighting . . . ironically it wasn’t a battle that finally broke the stalemate; rather it was the Communist Russian Revolution in 1918. When the troops had begun rebelling against the war in 1917, the largest revolt of all occurred in Russia. Led by Alexander Kerensky, Czar Nicholas II was overthrown and a democratic government was established. Unfortunately for the freedom of the Russian people, Kerensky’s government was soon blamed for the ongoing war. A second rebellion occurred in November of 1917 led by Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks (or “Red Russians”). The Communists promised the Russian people “bread, peace, and land.” They shot the Czar and his family and established a dictatorship. Russia became known as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics or the U.S.S.R. The supporters of the Czar (the “White Russians”) fought a three-year civil war against the Bolsheviks. At the end of WW1, the U.S. sent troops to help the White Russians—this was the beginning of bad blood between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. which would erupt in the Cold War after WWII. 29. But back to the stalemate . . . One of Lenin’s first actions was to pull Russia out of the war in Feb. of 1918. In the treaty signed with the Germans, Russia gave up a huge expanse of land in Eastern Europe. Germany, now with only one front but running out of men and supplies, decided on a last-ditch gamble. They renewed U-boat attacks on American shipping to block supplies headed for the Allies and launched a million-man assault on the Western Front. At first they made rapid progress, getting within 40 miles of Paris, but eventually the French and British, with aid from the American army, regained the upper hand and began to slowly push the Germans back toward Germany. The worn-out Germans, seeing the hand-writing on the wall, agreed to an armistice (end to the fighting) while still on French soil that took effect at 11:00 AM on November 11, 1918. 30. The U.S. entry into the war helped tip the psychological scale for the Allies more than making a military difference. Led by General Pershing, the bulk of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) only participated in the final 6 months of the war and fought in just a few battles, especially in the MeuseArgonne offensive. Eventually some 1.2 million “doughboys,” as the U.S. troops were nick-named, served in Europe, 85% of whom were drafted; 300,000 were black; an additional 250,000 women served, mostly as nurses and clerks. About 50,000 Americans were killed in battle; more died in the terrible world-wide influenza epidemic of 1918. 31. Once the guns were finally quiet, a “peace” (or twenty year time out) was negotiated in 1919. President Wilson hoped to achieve a peace based on his “Fourteen Points”—he probably promised too much and got peoples’ hopes too high. In the end, no country got all of what it wanted and many were disappointed by the treaty. 32. Wilson wanted a blameless peace, but the Allies were determined that Germany would be blamed and punished. Although Wilson was able to keep Germany for the most part from being divided up, the Allies saddled Germany with huge war reparations ($33 billion); insisted that Germany not be allowed to rebuild its military; and stripped off traditionally German territories along the French and Polish borders. However, several of Wilson’s 14 Points were included in the Treaty of Versailles, including the creation of a League of Nations. 33. Toward the end of the war the German leader Kaiser Wilhelm II had abdicated (given up power) and a new democratic government was organized called the Weimar Government. It was actually this government that signed armistice and agreed to the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. In the 1930s, Hitler came to power in part by blaming the Weimar Government for the defeat of Germany. After all, he argued, the German army had surrendered while still on French soil. 34. When Wilson brought his treaty back to the U.S. for ratification by the Senate, he discovered extreme opposition, especially to the League of Nations. Republican senators known as “Irreconcilables,” led by Henry Cabot Lodge, argued that if the U.S. signed the treaty and joined the League that the U.S. would be giving up some of its sovereignty, or independence. Wilson toured the country making speeches to build support for the treaty, but suffered a stroke. Both sides refused to compromise and the treaty was never ratified. Without U.S. participation in the League of Nations, the odds of its success in maintaining peace was very low. 35. As the U.S. entered the 1920s it returned to isolationism, focusing on internal issues in the U.S. 36. Blamed for the war and strapped with huge reparations, Germany became very resentful. When the Great Depression hit in the 1930s, Hitler took advantage and rose to power with a promise to restore German greatness.