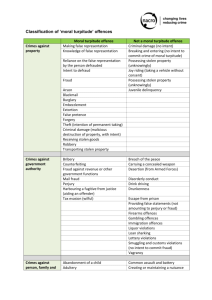

General Outline of Corporate and White Collar Crime Topics

advertisement