Introduction - EPSC - European Process Safety Centre

advertisement

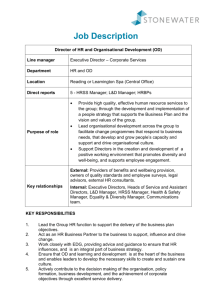

PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 Safety Culture Application Guide Final Version Prepared by Ronny Lardner Chartered Occupational Psychologist The Keil Centre 5 South Lauder Road Edinburgh EH9 2LJ United Kingdom Tel (00 44) 131 667 8059 Fax (00 44) 131 667 7946 E-mail ronny@keilcentre.co.uk www.keilcentre.co.uk 1 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 Table of Contents 1 2 3 4 Executive summary ..................................................................... 3 Overview ..................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................. 4 Safety culture theory ................................................................... 5 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 5 Safety culture & climate definitions ............................................................ 6 Model of safety culture ............................................................................... 7 Influence of national and organisational culture ......................................... 8 Safety sub-cultures .................................................................................. 10 Safety culture and health and safety outcomes ......................... 10 5.1.1 Organisational accidents ................................................................... 11 5.1.2 Individual occupational accidents ...................................................... 11 6 Defining a positive safety culture ............................................... 13 6.1 Features associated with a positive safety culture ................................... 14 7 Assessing safety culture............................................................ 15 7.1 Tips and good practice ............................................................................ 16 7.2 Quantitative methods (questionnaires) ..................................................... 18 7.3 Qualitative methods ................................................................................. 19 7.3.1 Interviews, focus groups and workshops .......................................... 19 7.3.2 Observation & ethnographic methods ............................................... 20 7.4 Triangulated methods .............................................................................. 21 7.4.1 Loughborough safety climate toolkit .................................................. 21 7.4.2 Safety Culture Maturity® model ........................................................ 21 7.5 Summary of safety culture assessment techniques ................................. 23 8 Links to behavioural safety and teamworking ............................ 24 8.1 Safety culture and behavioural safety ...................................................... 24 8.2 Safety culture and teamworking ............................................................... 24 9 General conclusions and discussion ......................................... 26 10 Key references .......................................................................... 27 11 Appendix 1: Relationship between safety climate and accident rates ................................................................................................ 30 2 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 1 Executive summary This safety culture application guide is designed to inform readers in the European process industries about safety culture theory, the features associated with a positive safety culture, and the link between a positive safety culture and health and safety performance. The guide also describes the main methods used to assess safety culture, and the relationship between safety culture, behavioural safety and teamworking. Key references are provided. 3 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 2 Overview This document is a guide to safety culture. The guide was prepared as part of the activities of the EU-funded PRISM project, which concerns human and organisational factors which affect health and safety in the European process industries. Within the PRISM project, Focus Group 1 is concerned with 3 topics: safety culture, teamworking and behavioural safety. This safety culture guide provides managers and safety specialists with an overview of safety culture theory, validity, measurement techniques and its relationship with behavioural safety and team-working. One of the needs identified earlier in the PRISM project by industry members of Focus Group 1 was the need to demonstrate how the topics of safety culture, team working and behavioural safety are integrated. The remainder of this guide is set out as follows: Section 3: An introduction Section 4: Outlines the theory underpinning safety culture Section 5: Describes the link between safety culture and health and safety performance Section 6: Lists the features associated with a positive safety culture Section 7: Reviews the main techniques for measuring safety culture Section 8: Discusses the relationship between safety culture and behaviour modification and team working Section 9: Draws general conclusions. 3 Introduction The process industries increasingly recognise the importance of the cultural aspects of safety management. This is due in part to the findings from investigations into major disasters in process industries (e.g. Flixborough and Piper Alpha) and other industries such as nuclear power (e.g. Three Mile Island and Chernobyl), marine transportation (Exxon Valdez and Zeebrugge) and passenger rail transportation (Ladbroke Grove and Clapham Junction). All these investigations concluded that systems broke down catastrophically, despite the use of complex engineering and technical safeguards. These disasters were not primarily caused by engineering failures, but by the action or inaction of the people running the system. “The causes in each case were 4 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 malpractices that had corrupted large parts of the socio-technical system”. (Lee, 1998 p217). A major focus over the past 150 years has been on developing the technical aspects of engineering systems to improve safety, and these efforts have been very successful. This success is demonstrated by the low accident rates in the majority of safety-critical industries, however many believe that a plateau has now been reached. The effectiveness of engineering and procedural solutions has highlighted the key role of human behaviour in the causation of the residual accidents. Some safety experts estimate that 80-90% of all industrial accidents are attributable to "human factors" causes (see Hoyos, 1995). It is now widely accepted that an effective way to further reduce accident rates is to address the social and organisational factors which influence safety performance. In parallel with the wider recognition of the importance of behavioural and psychological aspects of safety, the concept of organisational safety culture has come to the fore. Safety culture has been described as the most important theoretical development in health and safety research in the last decade (Pidgeon, 1991). The importance of safety culture is illustrated by the fact that although airlines across the world fly similar types of aircraft, with crews who are trained to similar standards, the risk to passengers varies by a factor of 42 across the world’s air carriers. Since these organizations have very similar technology, systems and structures, some argue that the difference in performance is largely due to systematic differences in the behaviour of their employees, in other words their safety culture (Reason, 1998). 4 Safety culture theory The term ‘safety culture’ was introduced by International Atomic Energy Agency in their report on the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster in 1986. The errors and violations of operating procedures which contributed to the Chernobyl disaster were seen by some as being evidence of a poor safety culture at the plant (Lee, 1998). The identification of a poor safety culture as a factor contributing to the accident led to a large number of studies investigating and attempting to measure safety culture in a variety of different high-risk, high-hazard industries. Although the importance of safety culture is widely accepted, there is still little agreement about what is meant by the term. To an extent, safety culture has been a victim of its own success, because the explosion of interest in safety culture has led to a range of conceptualisations, nearly one for each research team working in the area. A recent review of the research literature identified 16 separate safety culture definitions (Guldenmund, 2000). The issue is further confused by the related concept of safety climate. It appears that those who introduced the term safety culture ignored the earlier concept of safety climate described by Zohar (1980). Once the concept of safety culture became popular in the early 1990’s the question of its relationship with safety climate arose. Over the last decade several attempts have been made to distinguish between the two terms (see 5 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 Cox and Flin, 1998), but safety climate is still often used interchangeably with safety culture. The following section presents the most accepted definition of safety culture and a model that explains the relationship between safety culture and safety climate. 4.1 Safety culture & climate definitions The Advisory Committee on the Safety of Nuclear Installations (ACSNI) arguably produced the most widely accepted and comprehensive safety culture definition. They defined safety culture as ‘the product of individual and group values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies, and patterns of behaviour that determine commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, an organisation's health and safety management. Organisations with a positive safety culture are characterized by communications founded on mutual trust, by shared perceptions of the importance of safety and by the efficacy of preventive measures’ (ACSNI 1993, p23). Safety culture consists of values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies and behaviour of the people that make up the organisation. In an organisation with a positive safety culture there are high levels of trust, people agree that safety is important and that safety management systems are effective. This definition implies that a poor safety culture would be one where people do not trust each other, and do not share the perception that safety is important and that preventative measures are effective. Safety climate has been defined as “the workforce's attitudes and perceptions at a given place and time. It is a snapshot of the state of safety providing an indicator of the underlying safety culture of an organisation” (Mearns, Flin, Fleming & Gordon, 1997, P8). Safety climate also consists of attitudes and perceptions but does not contain values, competencies and behaviour. It differs from safety culture since it is specific to one time and location. It can be used as an indicator of the underlying safety culture. These definitions indicate that safety climate is a sub-set of safety culture, which is a broader, more enduring organisational feature. Safety culture influences workers’ (or group of workers) view of the world (i.e. what is important and how they interpret new information), and is relatively stable over time. It can be likened to the personality of the organisation. Safety culture transcends the organisational members that share the culture, is passed on to new members, and endures. In essence, safety culture is independent of people who are currently part of the organisation. The culture will exist after all these people have left. New members of the organisation informally ‘learn’ the safety culture, through observation, social feedback and trial and error. 6 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 Safety climate is more transitory and can be likened to a person’s mood, which changes in response to external events (Cox & Flin, 1998). Unfortunately, many researchers use the terms interchangeably, which has caused much of the confusion. In addition, questionnaires claiming to measure safety culture have very similar dimensions and statements as those claiming to measure safety climate (Cox & Flin 1998). As will be discussed below safety climate can be assessed via questionnaire, while safety culture arguably requires more qualitative measurement techniques. 4.2 Model of safety culture In his review of the safety culture research literature Guldenmund (2000) concluded “All in all, the models of safety culture are unsatisfactory to the extent that they do not embody a causal chain but rather specify some broad categories of interest and tentative relationships between those” (p243). Usefully, he developed a model of safety culture based on organisational culture theories and attitude models. Guldenmund (2000) proposed that safety culture consists of three levels, similar to the layers of an onion (see Figure 1). The core consists of ‘basic assumptions’ that are implicit, taken for granted, unconscious and shared by the entire organisation. These assumptions are not specific to safety, but are more general. For example, if written rules are regarded as critical then safety rules will also be considered as critical. The next layer is labelled ‘espoused values’ which in practice refers to the attitudes of organisational members. These attitudes are specific to safety, as opposed to general organisational factors. There are four broad groups of attitudes, namely attitudes towards hardware (e.g. plant design), management systems (e.g. safety systems), people (e.g. senior management) and behaviour (e.g. risk taking). The outer layer consists of artefacts or the outward expression of the safety culture. These would include equipment (e.g. personal protective equipment), behaviours, (e.g. using appropriate safety equipment or managers conducting safety tours), physical signs (e.g. posting number of days since last accident publicly) and safety performance (number of incidents). 7 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 Figure 1: Safety culture model Safety culture Basic Assumptions (Taken for granted/ unconscious) Safety climate Espoused values (Attitudes about: •Hardware •Systems •People •Behaviour) Artefacts (Visible signs) This model distinguishes between safety climate and safety culture, with safety climate consisting of the two outer layers of safety culture. Safety climate is a subset of safety culture and consists of espoused values and artefacts, which are specific to safety. These aspects can be measured quantitatively (e.g. via structured questionnaires) and are less stable. Basic assumptions, the inner-most element of safety culture, are more readily assessed by qualitative, non-numerical methods, as basic assumptions are by definition subconscious, taken-for-granted and therefore can only be inferred. Schein (1990) advocates ethnographic methods to measure organisational safety culture, to get at these basic assumptions. For example, via safety culture discussions with a large number of rail transport staff, it became apparent to an external facilitator that they held three different, subconscious definitions of safety: (1) train safety, (2) passenger safety and (3) staff safety. A very high priority was afforded to train and passenger safety, whereas staff safety was implicitly regarded as less important, and attracted less effort and resources. When this aspect of their safety culture was pointed out to the organisation, it was acknowledged that these implicit definitions did exist, and did influence how safety was managed, but had not previously been explicitly recognised. It is difficult to envisage how purely quantitative methods could have unearthed these types of subtleties in an organisation’s safety culture. It required qualitative methods and an external observer to notice. 4.3 Influence of national and organisational culture In the safety culture model shown in Figure 1, basic assumptions influence espoused values, which in turn determine artefacts (see Figure 2). This poses the question what influences basic assumptions? Theoretically, basic assumptions are influenced by the national and organisational cultures, although there is limited research evidence to 8 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 support this proposition. Although the basic assumptions do not have to be specific to safety, organisations that have strong safety cultures will have basic assumptions about the priority of safety, which are shared by organisational members. If organisations do not possess these basic assumptions, this would be an indicator of a poor safety culture. Figure 2: Relationship between national and organisational culture and safety culture National Culture Safety culture Basic Assumptions Espoused values Artefacts Organisational Culture The national culture is likely to influence the basic assumptions of organisational culture, as some basic assumptions will come from the national culture, for example the importance of rules and the acceptance of hierarchy (Hofstede, 1991). There is some evidence that safety culture varies significantly due to differences in national cultures. For example, Cheyne et al (2003) compared differences in safety climate across three member states of the European Union: UK, France and Spain. Known national cultural differences between these countries, such as (a) willingness to accept an unequal distribution of power, wealth and privilege (known as power distance) and (b) individualism were reflected in national responses to a safety climate questionnaire. However, Fleming, Rundmo, Mearns, Flin and Gordon (1995) measured safety climate on a number of offshore installations in the UK and Norwegian sectors of the North Sea. They found greater differences within their sample of UK installations and within their sample of Norwegian installations, than they found when all UK and all Norwegian installations were compared. In other words in this study, there was more variation in safety climate within a nation's offshore safety climate than between the UK and Norwegian nations. This indicates that installation safety climate differences are more significant than national cultural differences. 9 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 Moreover, a PRISM project case study by Labudde et al (2003) described how a US-owned company successfully established their own US-influenced organisational and safety culture on a greenfield site in Spain, where the prevailing local safety culture was at odds with the desired culture. In summary, there is limited evidence to support the notion that national culture does influence safety culture, however differences within countries may be larger than between countries. Also, the influence of national or regional culture does not preclude establishing a local site safety culture which differs markedly from other similar local sites. A strong safety culture can over-ride national or regional culture, if this safety culture is actively and consistently promoted. 4.4 Safety sub-cultures It is arguably meaningless to think of a large organisation having a single uniform safety culture throughout. This is particularly true when an organisation operates in several countries, merges with or acquires other companies, and employs a range of different types of professions, contractors and sub-contractors. Industry experience is that local variation in an organisation’s safety culture does exist, even within a single site. It follows that it should not be assumed that if an organisation has a generally strong safety culture, this exists at every local site. There is a lot of debate about the existence and impact of safety sub-cultures within an organisation. Despite the fact that there is limited research evidence supporting the existence of subcultures (although Mearns et al, 2001 provide some evidence), from a theoretical perspective safety sub-cultures will be present. As safety culture is shared by a group of workers, this group may be an organisation but it could be an occupational group, site or level of seniority Guldenmund (2000). It is likely that both safety sub-cultures and a wider safety culture can co-exist, but that the organisational safety culture will be more general or at a higher level of abstraction. Further research is required to investigate the relationship between safety sub-cultures and the safety culture of the entire organisation. 5 Safety culture and health and safety outcomes The utility of the safety culture concept depends upon the extent to which it influences health and safety outcomes. Theoretically there are two separate ways in which safety culture may influence health and safety. Firstly, the safety culture of an organisation may influence the likelihood of an organisational accident 1 occurring. Secondly the safety culture may influence the occupational accident rate. The 1 Comparatively rare, but often catastrophic, events that occur within complex modern technologies such as nuclear, petrochemical, and chemical plants, transport etc. Often involve multiple causes and actual or potential fatalities (after Reason, 1997) 10 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 evidence for a relationship between safety culture and organisational and occupational accidents is discussed separately below. 5.1.1 Organisational accidents Fortunately organisational accidents do not occur frequently, and therefore only limited research has been conducted to investigate the link between safety culture and organisational accidents. The evidence that links safety culture with organisational accidents comes from investigations into major disasters. As previously mentioned, many recent investigations into major disasters have a remarkable similarity in that they identify deficiencies in the safety culture as the underlying cause of the disasters. The failings of the organisational safety culture that contributed to the disasters are listed below for a sample of major disasters. Table 1: Link between safety culture and disasters Disaster Industry Chernobyl Nuclear power Safety culture deficiencies Violation or rules and procedures and overriding of safety systems Clapham Junction Rail transportation Poor working practices, high workload and a lack of management oversight Piper Alpha Offshore oil production Lack of management commitment, poor work practices, profits prioritised over safety Space Shuttle Aerospace Ability to see and not see dangers at the same time, production pressures Three Mile Island Nuclear power Poor understanding of the risks, inadequate competency Zeebrugge Marine transportation Lack of senior manager appreciation of the importance of safety, profit prioritised over safety and poorly-implemented management systems. The safety culture concept originated from the investigation into the Chernobyl nuclear disaster and it is clear that safety culture inadequacies have contributed to other disasters. While these high profile incidents have focused attention on safety culture there is a need for more scientific evidence of the importance of safety culture. The following section reviews the research concerning the relationship between individual occupational accidents and safety culture. 5.1.2 Individual occupational accidents Two main sources of evidence provide support for the validity of safety culture, namely (1) analysis of occupational accidents and (2) questionnaire studies. If safety culture influences occupational accident rates then it should be possible to identify safety culture factors that contributed to the cause of accidents. A review of 142 occupational accidents in two different sectors (steel industry and medicine) revealed 11 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 that between 35-40% of accident causes could be attributed to organisational factors, and of these a third were directly attributable to employee attitudes (van Vuuren, 2000). Although the author separates organisational factors into (a) structure, (b) strategy and goals and (c) safety culture, all of these are included in the definition of safety culture used in this guide. This study provides good evidence that safety culture is a causal factor in individual occupational accidents. The model of safety culture described in Figure 1 requires qualitative in addition to quantitative methods, to tap into basic assumptions. Unfortunately the majority of studies that link safety culture to safety outcomes use quantitative methods and therefore measure safety climate not culture. Numerous studies (Donald & Canter, 1994; Lee, 1995, Mearns et al 1997) have linked accidents to safety climate questionnaire responses, with lower accident rates being associated with positive safety attitudes. The majority of studies have adopted a similar methodology, which compares the responses of individuals who self-report accident involvement with those who report no accident involvement. Brown and Holmes (1986), using the instrument developed by Zohar (1980), found that accident and non-accident groups differed in their perceptions, with non-accident group reporting more positive perceptions. In the UK offshore oil and gas industry Mearns, et al (1997) found that accident and non-accident respondents differed in their assessment of safety measures, and on seven of the ten safety attitude factors, for example speaking up about safety and supervisor commitment to safety. Lee’s (1998) survey of 5198 nuclear power plant employees, found that accident and non-accident groups differed on 17 of the 19 safety climate factors measured. In a follow-up survey Lee and Harrison (2000) of 683 nuclear power employees on three sites they found that 24 of the 28 factors from their questionnaire were linked to accident performance. Research studies in other industrial domains (e.g. Donald and Canter 1994 and Niskanen, 1994) have also linked safety climate to safety performance. All of these studies take the individual as their unit of analysis and therefore have examined how individual attitudes are linked to individual accident involvement. The extent to which this indicates anything about organisational factors is questionable. There is a need to use the organisation as the unit of analysis rather than individuals. A study conducted by Simard and Marchand, (1994) randomly selected 258 plants from 20 manufacturing industries from Quebec, Canada. One hundred of the 258 agreed to participate in the study. The plants were split into high and low accident plants on the basis of their accident rate relative to their industry average. Data were collected through a battery of 13 questionnaires completed by senior managers, middle managers, worker representatives and first line supervisors. They found that the development of the safety management system and supervisor safety leadership differentiate between high and low accident organisations. While this is an interesting study, frontline workers were not surveyed, thus limiting the conclusions which can be drawn. A recent study conducted in the UK offshore oil and gas industry by Mearns, Whitaker, Flin, Gordon and O’Connor (2000) compared differences between 13 offshore 12 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 installations on self-completion questionnaires. Rank correlations were used to examine the relationship between company accident data and factors on the Offshore Safety Questionnaire. They found significant negative correlations between accident rates and health surveillance and promotion and safety auditing. The above indicates that there have been numerous studies demonstrating the link between self-report accident rates and safety attitudes. Taken together there is convincing evidence for the validity of the safety culture concept. Having said that, there is also a need for research that uses qualitative research techniques to investigate the relationship between basic assumptions and safety performance. Furthermore, only one study investigated health and none of the studies examined the relationship between safety culture and health outcomes. There is also a need for intervention studies to demonstrate a causative link between safety culture and health and safety outcomes. Finally, evidence of links between a strong safety culture and other aspects of organisational performance (e.g. productivity, quality, environmental performance) is sought by industry. 6 Defining a positive safety culture There has been little direct research on the features of a positive safety culture (Lee, 1998). There are a number of indirect sources of information to identify likely features of a positive safety culture. These include comparisons between high and low accident companies and safety climate surveys. Since safety culture is associated with occupational accidents then organisations that have a lower accident rate than similar organisations are also likely to have a positive safety culture. ACSNI (1993) conducted a comprehensive review of empirical research into the differences between high and low accident organisations. Low accident organisations were characterised by: Frequent, less formal communication about safety at all levels Good organisational learning Strong focus on safety by all Strongly committed senior management Democratic and co-operative leadership style High quality training, including safety training Good working conditions and housekeeping High job satisfaction Good industrial relations Selection and retention of employees who work steadily and safely 13 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 6.1 Features associated with a positive safety culture Evidence of the features of a positive safety culture is also provided by the results of safety climate surveys which linked questionnaire responses with either self-report accidents or company accident data. Appendix 1 summarises the findings from 6 studies which linked safety climate questionnaire responses to accident rates. Combining the characteristics of (a) low accident organisations and (b) the safety climate survey review in Appendix 1 produces the following features associated with a positive safety culture. These features are grouped below into the four attitude categories described in the safety culture model in Figure 1 (Guldenmund, 2000), with an additional category which refers to elements of the general organisational climate. 1. Hardware: Good plant design, working conditions and housekeeping Perception of low risk due to confidence in engineered systems 2. Management systems: Confidence in safety rules, procedures and measures Satisfaction with training Safety prioritised over profits and production Good organisational learning Good job communication 3. People: High levels of employee participation in safety Trust in workforce to manage risk High levels of management safety concern, involvement and commitment 4. Behaviour: Acceptance of personal responsibility for safety Frequent informal safety communication Willingness to speak up about safety A cautious approach to risk 5. Organisational climate factors: Low levels of job stress High levels of job satisfaction 14 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 7 Assessing safety culture The assessment of all three layers of safety culture (as described in Figure 1) requires the use of quantitative and qualitative methods. To date, no entirely satisfactory methodology for measuring all aspects of safety culture has been described in the research literature. Some researchers claim to measure safety culture (see Lee 1998) through self-completion questionnaires. In the model described in Figure 1 such questionnaire studies only measure the outer layers of safety culture, and do not get at the underlying assumptions. To get at these underlying assumptions requires phenomenological assessment techniques, such as interviews, trial and error, observations and ethnographic studies. It is important to note that this is an area of considerable academic debate. In practical terms the debate may only be one of semantics, since safety culture expresses itself through safety climate then it is likely that this can be used as an approximate measure of the safety culture. In addition, most existing assessment tools measure safety climate and not culture; therefore, organisations would need to develop their own safety culture assessment techniques. Instruments designed to assess safety climate are described below. There are a variety of methods that can be used to assess safety climate, and identify the main issues that need to be addressed. It is important to note that the very act of assessing the safety climate can have an impact on the culture. When people participate in the process they will wonder what is happening and how it is going to change their working environment. Frontline workers are likely to look for signs that indicate that management are doing this because they are truly interested in their safety, as opposed to some ulterior motive. The assessment method chosen can either reinforce the negative aspects of the current culture or be the beginning of the improvement process (Carroll, 1998). The assessment process should be consistent with the positive culture that is desired, for example one which gains a high degree of employee involvement. The potential assessment methods can be divided into three main types: Quantitative (e.g. safety climate survey tools) Qualitative (e.g. interviews, workshops and focus groups, observation, ethnographic methods) Triangulated methods, which combine quantitative and qualitative methods One difference between these methods is the degree of confidentiality and security they offer to the participants. Another difference is the degree of structure they impose and the ease of analysing the output. Irrespective of the specific assessment method used there are a number of tips and good practice guidelines, which are outlined below, followed by a description of the three main types of assessment methods. 15 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 7.1 Tips and good practice The following tips relate to the five main stages involved in assessing safety culture or climate: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Gaining senior management commitment Involving frontline employees Assessing attitudes and perceptions Analysing and feeding back results Agreeing interventions via workforce consultation Tip 1: Gain managers informed commitment to the assessment process It is critical that senior management understand the assessment process and that they are committed to making it work. The importance of senior management involvement and commitment cannot be understated, because if the assessment process goes ahead without this, then it is not only likely to fail, but may actually damage the safety culture. In practice management commitment can be tested and secured by holding a senior management workshop before any announcement about the assessment process commences. The majority of the senior management team should attend this workshop, which outlines the various assessment options, the potential problems and the type of results that will be obtained. Managers need to consider how they would respond if the results are negative and specifically if they are negative about management. They also need to consider public reaction to negative results, as it will be difficult to control them once they have been shared with the workforce. It must be emphasised to management that, if they think they may want to suppress the results if they are negative, then the assessment should not go ahead. Conducting a survey and not sharing the results with the workforce is likely to increase distrust and ‘prove’ to frontline staff that managers are not really committed to safety. Tip 2: Involve frontline workers in assessment, interpretation and identifying interventions Once managers are signed on, then frontline workers need to be involved. The most suitable ways for involvement will depend on the method of assessment, number of workers and the organisational structure. With a large workforce, a workforce steering committee containing a representative sample of workers from each occupation and location is often effective. If the workforce is smaller or group sessions are being used, then involvement can be achieved by giving everyone an opportunity to participate actively in the assessment process. It is important to provide workers with an opportunity to ask questions and make suggestions. Irrespective of how frontline workers are involved, it is important they are involved before assessment, and included in interpreting findings and specifying interventions. 16 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 Tip 3: Obtain a high response rate by making participation easy Each assessment process has its own set of specific guidelines, but there are a number of generic issues to be considered. Obtaining a representative sample is critical. It is important that the sample is representative of all occupational groups, levels of seniority, departments, locations and contractor staff. If a self-completion questionnaire is being distributed to the entire workforce then a high response rate (over 70%) is desirable. If only 40% of the workforce respond then it is likely that those who made the effort to complete the survey have different attitudes than those who did not complete the survey. Lee (1998) achieved a high response rate by distributing questionnaires at weekly departmental meetings, and providing people with time during the meeting to complete the questionnaire. In addition, the company prepared a short video with a message from a senior manager outlining their commitment to the process and how the data would be used. Returning the questionnaires for analysis was also made easy by providing special post boxes for preaddressed envelopes. Maximising participant’s confidence in the confidentiality of their responses is also important. If people are concerned that their responses could be used against them, they are unlikely to respond honestly or at all. If a self-completion questionnaire is being used then it should be anonymous and the number of demographic questions should be limited to avoid some respondents being identifiable (e.g. only female engineer with the company). If interviews or workshops are being used then the choice of facilitator is critical, as he or she must be trusted. In addition, participants should be at the same level of seniority to avoid more junior staff being intimidated. Tip 4: Involve participants in the interpretation of the results Assessing safety attitudes and perceptions is unlikely to be of much benefit if the responses are not interpreted correctly. Questionnaire rating scale responses are often difficult to interpret, as it can be difficult to know what constitutes a positive response. Interpretation of the responses can be assisted through input from participants. It is therefore recommended to present the results to a sample of the workforce and ask them to interpret the results. The results should be presented back in a simple form without complex statistical information. Tip 5: Take actions quickly, which are directly linked to the results Once the safety climate has been measured then interventions to improve the safety culture will be required. Assessment alone is not enough. If people give their perspectives on safety they expect action to be taken. The people in the best position to identify suitable interventions are often those at the sharp end, i.e. frontline staff. The specification of interventions should be a joint effort between senior management who control resources, and frontline staff who have to make any interventions work in practice. A lack of timely action is likely to be judged as a lack of management commitment to safety and therefore make things worse not better. Too much analysis 17 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 of results can often lead to delay, it is therefore better to take some immediate actions. It is also critical to explicitly link actions to the results of the safety climate measurement, to demonstrate that actions are being taken. This process should be consistent with the positive culture that is desired, i.e. it should be participative and based on mutual trust. Additional tips and insights on safety climate assessment can be gained from a published evaluation of users of the UK Health and Safety Executive’s Health and Safety Climate Survey Tool (HSE, 2002). 7.2 Quantitative methods (questionnaires) Safety climate surveys are the most commonly used method to obtain information about safety culture. Safety climate questionnaires measure ‘safety attitudes’ with positive attitudes to safety being considered to be the most important aspect of a ‘good’ safety culture (Cox & Cox, 1991; Donald & Canter, 1994; Lee, 1995, Mearns et al (1997). Questionnaire studies involve employees indicating the extent to which they agree or disagree with a range of statements about safety e.g. ‘senior management demonstrate their commitment to safety’. Although there are a large number of safety climate questionnaires containing different statements to measure safety climate, a number of common factors have emerged. A recent review (Flin, Mearns, O’Connor & Bryden, 2000) has identified the following six common themes: Management/ supervisor commitment to safety Safety systems Risk perception and self-reported risk taking Work pressure Competence Procedures and rules The majority of safety climate questionnaires are commercial products sold by health and safety consultancies or academic institutions. There are some exceptions, such as the UK Health and Safety Executive’s Climate Survey Tool (HSE, 1997) and Loughbrough University’s freely-available downloadable offshore safety climate assessment toolkit - Loughborough University, (undated). . The safety climate questionnaire tools currently in use are arguably deficient in a number of respects. Firstly, the six common concepts identified in the Flin et al (2000) review did not include trust or the perceived effectiveness of preventive measures, yet these are key components of safety culture. Secondly, while some studies (e.g. Mearns et al, 1997) have included measures of perceived risk, none have investigated other issues surrounding risk such as norms for dealing with risk or risk acceptance, yet these are key components of safety culture from a theoretical perspective. The two main strengths of safety climate tools are that: 18 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 (a) employees can respond anonymously, and (b) the results are expressed in numerical form making it easy to compare results from different sites, or at different points in time The main weaknesses of this approach are that: (a) it can be difficult to turn results into actions to improve safety, and (b) it is often necessary to hold further workshops or interviews with staff to clarify the significance of the results. 7.3 Qualitative methods 7.3.1 Interviews, focus groups and workshops Interviews and workshops have been used less frequently to assess safety culture, and validated techniques are not widely available. Organisations that have used these techniques have tended to develop them in-house. The assessment process should follow the five tips outlined above, in addition to the following considerations. Since there are few commercially available tools, it may be necessary to develop an assessment process. Topics to focus upon Firstly, a series of questions or discussion points need to be developed. These should be open questions to facilitate discussion, for example “Can you describe an event which illustrates managers attitudes to safety?” The assessment process should include questions for each the main elements of safety culture. Participants should be encouraged to identify potential solutions to issues identified and to make general suggestions about how the safety culture can be improved. Facilitation The success of interviews, focus groups and workshops is dependent on participants’ willingness to speak openly. It is recommended that facilitators external to the group be used for these methods, to ensure that participants are willing to be honest. If the process is being conducted internally the openness of participants will be influenced by the existing culture and level of trust in the organisation. The following will enhance openness: Establish clear ground rules at the beginning of the session, requesting that participants do not name individuals Make it clear to participants that they do not have to answer any question, but their perspectives are valuable and the aim of the process is to improve safety for all. Ensure focus group or workshop participants are at the same level of seniority 19 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 Explain what information will be collected, who will see it and how it is going to be used Do not request personal details of individuals and only use first names. Use a suitable room where you are unlikely to be interrupted or over heard. Analysis Qualitative techniques produce a large amount of information, which can be overwhelming. Data analysis is facilitated by the use of a coding scheme that is based on the elements of safety culture described in section 6.1. Expert assistant may be required for this phase of the assessment process. The two main strengths of qualitative techniques are that: (a) they provide a rich picture of the cultural issues and (b) the participants can also suggest solutions to the issues they identify. The main weaknesses of qualitative techniques are that: (a) the lack of a validated structure means that important issues may be missed (b) participants may be unwilling to be open and honest if confidence and trust are low (c) it is not easy to make comparisons between sites or over time. 7.3.2 Observation & ethnographic methods If an anthropologist wished to understand a different culture, they would not typically reach for a questionnaire. An anthropologist would be more likely to live amongst the inhabitants of that culture, observing their habits and customs at close quarters over an extended period of time, and make comparisons with other cultures they are familiar with. Similarly, a new member of, or visitor to, an organisation can offer insights into the existing safety culture, by observing and drawing comparisons with other safety cultures they have experienced, and current research findings and best practice. This observational method of safety culture assessment is used when internal or external safety auditors, government health and safety regulators, external safety consultants etc. visit a site to assess the adequacy of their health and safety arrangements. For example, a high-hazard manufacturing site invited a safety specialist from another company to visit for a few days, tour the site, make observations, and provide feedback on the site safety culture and identify areas for improvement. When visiting one part of the site, the visitor was met by the local health and safety advisor. The advisor was going to act as a guide and explain local health and safety issues. The visiting safety specialist interpreted this as a negative indication that health and safety was not truly owned by line management, as they had sent the local health and safety advisor to represent them rather than coming themselves. This was quite different from what the visiting safety specialist would have 20 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 expected to find on a site with a strong line management commitment to health and safety. The significance of sending the local health and safety advisor was not noticed by site employees, as this was “how they did things round here”, and was to them an invisible part of their basic assumptions about how safety should be managed. The two main strengths of observation & ethnographic methods are that: (a) they provide a rich picture of the cultural issues and (b) they can uncover basic assumptions at the core of safety culture The main weaknesses of observation & ethnographic methods are that: (a) the lack of a validated structure may mean that important issues are missed (b) an experienced external observer is required, who is sensitive to differences in safety culture (b) observations over an extended period of time may be required, to ensure conclusions are not drawn on the basis of isolated, atypical incidents (c) it is not easy to make comparisons between sites or over time. 7.4 Triangulated methods An important research concept in the social sciences is triangulation of methods. Triangulation refers to “the combination of several methodologies in order to study one phenomenon”. For example, the strengths of quantitative and qualitative methods for assessing safety culture can be combined, whilst overcoming the weaknesses of a single method. Numerical comparisons can be made, whilst explanatory qualitative insight is maintained. 7.4.1 Loughborough safety climate toolkit The Loughborough safety climate toolkit (Loughborough University, undated) involves triangulation of methods. In addition to a quantitative questionnaire, this toolkit includes the option to conduct interviews, focus groups and behavioural observations. 7.4.2 Safety Culture Maturity® model The Safety Culture Maturity®2 Model is also a triangulated method, as it combines quantitative assessment with qualitative exploration of safety culture via focus groups. Developed by The Keil Centre, the Safety Culture Maturity® Model has five levels of safety culture maturity, and ten elements, which are described below. The ten elements are based on a review of the safety culture 2 Safety Culture Maturity is a registered trade mark of The Keil Centre Ltd 21 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 literature (see Lardner, Fleming and Joyner, 2001). A site’s overall level of maturity is determined on the basis of the maturity level for each of the ten elements. Safety sub-cultures are also defined and examined. It is unlikely that an organisation will be at the same level on each of the ten safety culture elements of the SCM®. Management commitment and visibility Safety communication Productivity versus safety Learning organisation Health and safety resources Participation in safety Risk-taking behaviour Trust between management and front-line staff Industrial relations and job satisfaction Safety training This assessment method involves workshops with 10-12 participants, and is conducted in two stages. Initially participants select the level of Safety Culture Maturity® which best describes the current situation in their organisation, location or department. Once this is completed the results of the groups are displayed and participants provide more detail about each element. They then identify actions to improve the safety culture within the organisation. The three main strengths of the Safety Culture Maturity® model technique are: (a) it is possible to compare results from different sites, teams, or at different points in time (b) it provides a rich picture of the cultural issues and (c) the participants suggest solutions to the issues they identify. The two main weaknesses of this method are: (a) it is resource-intensive, requiring a series of facilitated workshops (b) the group workshop format can limit individual confidentiality A further description of the development of this method and an industrial case study by Lardner, Fleming and Joyner (2001) is available. 22 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 7.5 Summary of safety culture assessment techniques The appropriateness of the assessment technique depends on the requirements of the organisation. Table 4 below provides a summary to aid selection of the most appropriate method. Remember that methods can be triangulated, for example by combining quantitative and qualitative methods. Table 4: Comparison between assessment methods Criteria Cost Quantitative Utility of results Strengths Limitations Purchase of instrument/ development of instrument Staff time to complete questionnaire Analysing results Meeting with staff to identify interventions Produces a large amount of numerical data Results may be difficult to link to interventions Efficient way of collecting data about employee’s perceptions and attitudes to safety Can allow benchmarking and comparison between sites Limited employee involvement Employees often do not see the link between the survey and interventions Hard to know exact meaning of results Assessment methods Qualitative Triangulated methods Time to develop interview schedule External assistance Workforce time Time to analyse results and identify actions External assistance Workforce and management time Produces a large amount of written data Data can be difficult to analyse and interpret High face validity – appears relevant Interventions can be directly linked to interviews Some employee involvement Qualitative data can be difficult to analyse and interpret Can help with focus on solutions Confidentiality can be a problem Results can be biased if level of trust is low Relatively time consuming Difficult to compare results across sites or over time 23 High face validity – appears relevant Can compare and contrast different types of data Can lead to higher confidence in results External assistance may be required Time-consuming Lack of comparable norm data for qualitative data PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 8 Links to behavioural safety and teamworking Focus Group 1 of the PRISM project concerned 3 topics: safety culture, behavioural safety and teamworking. PRISM industry members were particularly interested in how these three topics were inter-related. The following sections of the report outline the relevant links. 8.1 Safety culture and behavioural safety Current safety culture assessment techniques identify general organisational strengths and weaknesses, which are not usually directly linked to specific behaviours. This can limit the identification of specific behaviours which need to be adopted or promoted to enhance a positive safety culture. Furthermore, the specific behaviours required to promote a positive safety culture are likely to vary over time and between organisations. It is therefore often necessary for an organisation to further analyse the results of their safety culture measurement processes in order to identify the specific behaviours required to promote or maintain a positive safety culture. Once these behaviours have been described, one way to promote them is via a behavioural safety programme. Research evidence (Komaki, 2000) suggests that behavioural safety programmes can enhance the safety climate of an organisation. They provide an opportunity for management to demonstrate their visible commitment to health and safety, involve employees, and provide an opportunity to learn about the behavioural causes of accidents, and preventative measures. For example, one behavioural safety study (Cooper and Phillips, 1994) measured site safety climate before and after a behavioural safety programme was implemented. Over a one-year period, significant positive changes in the plant’s safety climate occurred, suggesting the programme’s impact extended beyond its initial focus on behaviour. Other research (Fleming & Lardner, 2000) suggests that behavioural safety programmes need to be matched to the maturity of an organisation’s existing safety culture. This suggests a two-way relationship between behavioural safety programmes and safety culture. The existing level of maturity determines the type of behavioural safety programme which is appropriate and is likely to succeed, and this behavioural safety programme will in turn enhance the maturity of the organisation’s safety culture. 8.2 Safety culture and teamworking There is very little research that has investigated the relationship between safety culture and team working. One study in Australia (Neal, Griffin & Hart, 2000) tested the extent to which a socio-technical systems theory applied to safety climate. Sociotechnical systems theory advocates a teamworking approach to organisational design 24 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 as this facilitates variance (e.g. process upsets, occupational accidents) being controlled at source. This increases organisational effectiveness, as the people who are in the best position to control the variance are those who work with the system on a day-to-day basis. In addition, giving workers control over variance increases their motivation. A large questionnaire study conducted in Australia (Neal et al, 2000) provides evidence that teamworking is likely to have a positive impact on safety culture, by increasing safety knowledge and motivation (see figure 3 below). These findings are supported by two case studies conducted in the UK process and nuclear industries (Lardner 1999) which concluded safety attitudes and motivation improved following the introduction of team working initiatives. It was also noted that teamworking could have a negative impact on safety performance if the team only had production goals, and were not also set health and safety goals. Although there is limited research evidence, it appears that properly-implemented teamworking is likely to enhance an organisation’s safety culture, principally via increased employee involvement in managing health and safety. Figure 3: Socio-technical system model of safety culture. ANTECEDENTS DETERMINANTS Safety Knowledge Organisational Climate COMPONENTS Safety Compliance Safety Climate Safety Motivation Behavioural Safety/ Team-working etc. Culture/Climate Safety Participation Safety Behaviour & Employee Involvement Additional insights into the relationship between safety culture, teamworking and behavioural safety are provided by a case study completed during the PRISM project (Labudde et al, 2003). This case study of DuPont’s Nomex plant in the Asturias region of Spain demonstrated how it is possible to design and construct the work and safety culture you desire, despite the fact that this may run counter to the prevailing local industrial safety culture. DuPont was able to capitalise on the fact that the Nomex 25 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 plant was a greenfield site, therefore all employees were selected and hired to be compatible with the desired work and safety culture. Interestingly, DuPont chose a flat organisational structure with self-managing production teams. This type of team design reinforces the need for all employees to take personal responsibility and develop high levels of competence. The wellknow DuPont STOP behavioural safety observation system was adapted for use with teams who have no direct supervision in the team. The integration of safety culture development, teamworking and behavioural safety at the Nomex plant has made a significant contribution to the Asturias site’s exceptionally strong safety performance over the first ten years of its operation. 9 General conclusions and discussion Safety culture is now generally accepted as a “good thing” to have, and there is a growing consensus about the main features of a positive safety culture. The links between safety culture and organisational and occupational accidents are becoming increasingly clear. A local plant’s safety culture is likely to be influenced by national cultural differences, but this does not mean incoming organisations cannot develop their own safety cultures. Rather, they will have to take into account existing national cultural influences as they develop their own. There are a range of methods available to assess safety culture. A reciprocal relationship exists between safety culture, behavioural safety and teamworking. Behavioural safety and teamworking both can support the development of a mature safety culture with high levels of employee involvement. Similarly a strong safety culture allows teamworking and behavioural safety to flourish. 26 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 10 Key references ACSNI (1993) Human factors study group Third report: Organising for safety. London: HMSO Brown. R. L. & Holmes, H. (1986). The use of factor-analytic procedure for assessing the validity of an employee safety climate model. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 18, pp 289-297 Carroll, J (1998) Safety culture as an ongoing process: culture surveys as opportunities for enquiry and change. Work and Stress, 12, 272-284. Cheyne, A, Oliver, A, and Tomas, J (2003) Differences in safety climate in three European countries Proceedings of 2003 British Psychological Society Occupational Psychology Conference, pages 87 – 91 Cooper, M and Phillips, R (1994) Validation of a safety climate measure Proceedings of 1994 British Psychological Society Occupational Psychology Conference Cox, S. & Cox, T. (1991). The structure of employee attitudes to safety: a European example. Work and Stress, 5, 93-106. Cox, S. & Cox, T. (1996). Safety, systems and people. Oxford: ButterworthHeinemann. Cox, S. & Flin, R. (1998). Safety culture: philosopher’s stone or man of straw? Work and Stress, 12, 189-201 Donald, I. & Canter, D. (1994). Employee attitudes and safety in the chemical industry. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries, 7, 203208. Fleming, M. and Lardner, R. (2000). Behaviour Modification Programmes: Establishing Best Practice. HSE Books. Fleming, M., Rundmo, T., Mearns, K,. Flin, R. and Gordon, R. (1995, December) Risk perception and safety a comparative study of UK and Norwegian offshore workers. Paper presented at the work and well-being conference, Nottingham. Flin, R. (1998) Safety Culture: Identifying and measuring the common features. Paper presented at the International Association of Applied Psychology’ conference. San Francisco. August. Flin, R., Mearns, K., O’Connor, P. & Bryden, R. (2000). Safety climate: Identifying the common features. Safety Science, 34, 177-192. 27 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 Guldenmund, F.W. (2000). The nature of safety culture: A review of theory and research. Safety Science, 34, 215-257 Hofstede, G (1991) Cultures and organisations, software of the mind, Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill. Hoyos, C.G. (1995). Occupational safety: Progress in understanding the basic aspects of safe and unsafe behaviour. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 44 (3), 235-250. HSE (1997) Health and Safety Climate Survey Tool, HSE Books ISBN 0 7176 1462 X – see www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/misc097.pdf HSE (2002) Evaluating the effectiveness of the Health and Safety Executive’s Health and Safety Climate Survey Tool – Research Report 042 – available via www.hsebooks.co.uk Komaki, J et al (2000). A rich and rigorous examination of applied behaviour analysis research in the world of work. International Review of Industrial and Organisational Psychology, 15, 265-367. Labudde, H; Lardner, R. and Martinez, F (2003) Safety Culture by Design – PRISM case study : European Process Safety Centre Lardner, R. (1999). Safety implications of self-managed teams HSE, OSD Report . Suffolk: HSE Books. Lardner, R.; Fleming, M, and Joyner, P. (2001) Towards a mature safety culture in Proceedings of Hazards XVI Institution of Chemical Engineers Conference, Manchester,UK, 6-8 November 2001 Lee, T. and Harrison, K. (2000) Assessing safety culture in nuclear power stations. Safety Science, 34, pp61-97. Lee, T. R., (1998). Assessment of safety culture of a nuclear reprocessing plant. Work and Stress, 12, 217-237. Lee, T.R. (1995). The role of attitudes in the safety culture and how to change them. Paper presented at the Conference on ‘Understanding Risk Perception’. Aberdeen: Offshore Management Centre, The Robert Gordon University. Loughborough University (undated) Offshore Safety Climate Assessment Toolkit– see http://www.lboro.ac.uk/departments/bs/JIP/ Mearns, K., Flin, R., Fleming, M. & Gordon, R. (1997). Human and organisational factors in offshore safety. HSE, OSD Report . Suffolk: HSE Books. 28 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 Mearns, K., Whitaker, S., Flin, R., Gordon, R. and O’Connor, P. (2000) Factoring the human into safety: Translating research into practice. Volume 1 OTO 2000 061. Suffolk: HSE Books. Neal, A., Griffin, M.A. and Hart, P.M. (2000) The impact of organizational climate on safety climate and individual behaviour. Safety Science, 34, pp 99109 Niskanen, T. (1994). Safety climate in the road administration. Safety Science, 17, pp237-255. Pidgeon, N. (1991). Safety culture and risk management in organisations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 22, 129-140. Reason, J. (1998). Managing the risks of organizational accidents. Ashgate. Aldershot. Schein, E. H. (1990) Organizational culture. American Psychologist, 45 (2) pp109-119 Simard, M. & Marchand, A. (1994). The behaviour of the first line supervisor in accident prevention and effectiveness in occupational safety. Safety Science, 17, pp169-185. van Vuuren, W. (2000) Cultural influences on risk and risk management: six case studies. Safety Science, 34, pp 31-45 Zohar, D. (1980). Safety climate in industrial organisations: theoretical and applied implications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65 (1), 96-102. 29 PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 11 Appendix 1: Relationship between safety climate and accident rates Research team Brown and Holmes (1986) Lee (1998) Mearns et al (1997) Industry Features Manufacturing High management concern for safety High management safety activity Nuclear power Confidence in safety procedures Workers cautious about risk Lower perception of risk Trust in workforce Efficient Permit To Work (PTW) system Workers in favour of PTW Workers interested and contented in their jobs Good working relationships Workers receive praise Safety rules are understood Safety rules are clear Training is satisfactory Effective staff selection High levels of participation in safety Safety actions taken by management Individuals have control over safety Good plant design Good job communication High levels of safety behaviour Offshore oil 30 Accident data Link self report accidents to questionnaire responses Link questionnaire responses to self report accident data. Link self report accidents to questionnaire PRISM FG1 Safety Culture Application Guide – Final Version 1.1 – 8 August 2003 Research team Industry Mearns et al (2000) Offshore oil industry Niskanen (1994) Road construction Rundmo (1992, 1994) Offshore oil industry Features Lower risk perception Satisfaction with safety measures Willingness to speak up about safety Not feeling under pressure to violate procedures Positive attitudes to rules and procedures Personal responsibility for safety Perceived management Commitment to safety, Willingness to report accidents. Lower work pressure Effective supervision Value of work Safety prioritised over production Lower perception of risk Low levels of job stress Good working conditions Satisfied with safety measures Low levels of sensation seeking 31 Accident data responses Used Discriminant Function analysis (DFA) to identify the questionnaire factors that differentiated respondents who reported and did not report being involved in an accident Differences between work sites accident rates and reported attitudes LISREL models used to link factors with self report accidents