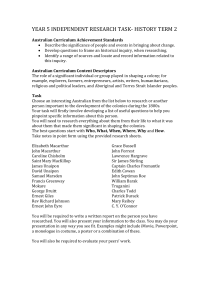

management and research implications

advertisement

Managing People and Change: Comparing Organisations and Management in Australia, China, India and South Africa Janice Jones Lecturer, School of Commerce Flinders University of South Australia GPO Box 2100 Adelaide South Australia 5001 Telephone: +61 8 82012707 Facsimile: +61 8 82012644 Email: Janice.Jones@flinders.edu.au and Terence Jackson Centre for Cross Cultural Management Research EAP European School of Management 12 Merton Street Oxford OX1 England Telepone: +55 1865 263212 Email: tjackson@eap.net SCHOOL OF COMMERCE RESEARCH PAPER SERIES: 01-5 ISSN: 1441-3906 1 ABSTRACT This study investigates perceptions and attitudes of Australian, Chinese, Indian and South African managers to managing people and organisations. Comparisons between managers and organisations from Australia and China, India and South Africa reveal cross-cultural similarities and differences exist. While similarities exist with other Anglo countries there are exceptions, including significant differences between the direction of Australian management commitment and China, India and South Africa. The implications of these differences for international joint ventures are explored. The implications of motivators considered important to Chinese managers in the present study are also addressed. 2 INTRODUCTION Over the last 15 years, there have been significant changes in the Australian economy. With the aim of exposing the Australian economy to international competition, successive Australian governments initiated a series of macro- and micro-economic reforms including floating of the dollar, phasing out tariffs, waterfront, shipping and air-freight reform, financial deregulation (Edwards, O’Reilly and Schuwwalow, 1997) and the gradual freeing up of the labour market. Key elements of the micro-economic reform agenda also included workplace change, public sector reform and privatisation (ACIRRT, 1999). These policy reforms have transformed the so-called ‘Australian settlement’ to a new ‘post industrial settlement’ Australia, in which traditional manufacturing industries (the old protected ‘smokestack’ industries) have been replaced by the so-called ‘elaborately transformed manufactures’ (ETMs) and service sector (Burrell, 1999). As a result of these developments, Australian organisations faced considerable competitive pressures. Furthermore, as the old protectionism characteristic of Australian industrial policy gave way to a more free-market driven approach in tune with the realities of the new global economy, Australian companies and workers have been forced to change their approaches to productivity, wages and workplace practices (Burrell, 1999). These general trends within the Australian economy reflect a global tendency over the last two decades for national economies to move towards a free-market system. Major events within the Soviet bloc at the end of the 1980s, the liberalization of the Chinese economy and its opening up to east-west joint ventures, the end of apartheid and sanctions in South Africa, and major reforms in India shifting the economy away from state protectionism are examples of this global trend. 3 This paper builds upon a study previously undertaken by Jones and Jackson (2000) as part of a research effort to reconcile differences in management approaches towards managing people and organisations in the international context. The principal objective in this paper is to compare data on Australian management and organisations with data from China, India and South Africa in order to highlight both common and different organisational dynamics within countries which have undergone fundamental transitions towards free market economies. Such a comparison is of interest for the following reasons. The Chinese market is the fastest growing economy in Asia with economic growth of 7.1 per cent in 1999 (Austrade, 2000). As one of the worlds’ fastest developing economies (Wright, Mitsuhashi & Chau, 1998) and the world's most populous nation with a growing middle class, the People's Republic of China represents an opportunity as a potential major market of the future. It is also a challenge for Australian firms and their managers wanting to do business in China, as the Chinese culture differs substantially from that of Western countries. Much of China’s economic growth has come from the opening of the economy to direct foreign investment, most often in the form of joint ventures with Chinese partner organisations, and multinational corporations (Lindholm, 1999). Committed Australian direct investment in China totalled 5 billion Australian dollars while realised Australian direct investment in China totalled 1.5 billion dollars (Austrade, 2000). Australia is now the fifth largest investor in China’s special economic development areas of Shenzen, Guangzhou and Zhuhon (Harris, 1994). India’s economy has been growing at the rate of approximately 6 per cent for the last three years and is expected to grow at around the same rate in the year 2000. India is the world’s second most populated country and has emerged as a rapidly growing market for Australian 4 goods and services. Exports of ETMs from Australia have increased from around $20 million in the late 1980s to approximately $190 million in 1998/99. Paralleling this trend in exports is the increase in Australian investment in India. Austrade (2000) estimates that current investment exceeds $1 billion covering over 100 companies, compared to approximately $250 million and 30 joint ventures in the early 1990s. South Africa is yet another large market undergoing steady growth. Australian exports to South Africa have increased rapidly over the last five years at a trend growth rate of 35 percent per annum, reaching A$ 1.013 billion in 1996/97. South Africa is Australia’s fastest growing market for ETMs with a trend growth rate of 42 percent over the last five years (Austrade, 2000). As more Australian businesses expand into these countries through foreign direct investment, exporting, the establishment of branches or foreign subsidiaries, joint ventures and strategic alliances, managers must not only meet the standard challenges of managing, but also contend with the additional challenge of doing so in differing political, legal and cultural environments. It is in the context of managing the relationships of individuals, groups and organisations of different cultural backgrounds, that companies have commonly experienced difficulties (Stening and Ngan, 1997). Comparative studies can be an invaluable source used to generate knowledge of both similarities and differences in management systems of trading partners that may assist Australian managers develop appropriate organisational and managerial practices in such countries. The paper is organised in the following manner. The first section describes the research method. This is followed by the discussion of results. We then examine key cross-cultural 5 differences. The article concludes with a discussion of the implications of such cross-cultural differences. Suggestions for further research are also addressed. RESEARCH METHOD Procedure The design of the study was essentially exploratory in that we set out to capture broad-ranging information about management and organisation using a short questionnaire which could be replicable in different countries, and would provide comparison with previous studies. The first part of the questionnaire based predominantly on prior cross-cultural studies of organisational factors includes items on strategy, structure, decision-making, control, character in terms of ethics, success and change, internal policies, climate, external policies, management expertise and people orientation (Vertinski, Tse, Wehrung and Lee, 1990; Hofstede, 1994; Reynolds, 1986; Laurent, 1989). Managers were asked to respond to items on the basis of their organisation currently, the way it is changing, and how they would like it to change. They were asked to indicate, using a five-point Likert scale, whether “their organisation is like this at the moment”, “the way it is going in the future” and “the way they would like it to be” (with 1 “being not like this at all”, and 5 “exactly like this”). The second part of the questionnaire comprises a subsection of ten items derived from motivation theory and informed by cross-cultural studies which suggest that commonalties as well as differences in managerial motivation exist among different national cultures (England, 1986; Hui, 1990; Alpander and Carter, 1991). The items measure needs for economic and psychological security, control, self-enhancement, autonomy, independence, belonging, personal self worth, belonging and personal development. The next sub-section focuses on the direction of management commitment (commitment towards: self; the group; the organisation; people; results; business objectives regardless of methods; ethical principles; work; and, relatives). The items draw on aspects of collectivism and individualism (Hofstede, 6 1980, Wagner, 1995) as well as aspects of humanism and instrumentalism (Jackson, 1999). The next sub-section looks at principles by which managers operate and make decisions (locus of control, deontological and teleological decision making, trust or mistrust of human nature, and status or achievement orientations). Items focus more specifically on cultural factors drawing widely on the literature and accessing information on perceptions of human nature (Kluckholn and Strodtbeck, 1961) and mirroring McGregor’s (1960) concept of theory X and theory Y (see also Evans, Hau and Sculli, 1989), locus of control (Trompenaars, 1993, after Rotter, 1966), utilitarianism and formalism in decision making (Jackson, T. 1993), and ascribed and achieved status (Trompanaars, 1993). The final sub-section accesses information on management practices (reliance on hierarchy, use of rank, levels of participation and egalitarianism, communicating and providing information, and degree of confrontation) and drawing on such aspects in the literature as respect for hierarchy (Kluckholn and Strodtbeck, 1961; Evans Hau and Sculli, 1989). Managers were asked to respond to items on the basis of “me as a manager”, “managers generally in my organisation”, and “the type of manager required for the future of the organisation”. They were asked to indicate using a five-point Likert scale with 1 “being least like this” and 5 “exactly like this”. Sample The sampling frame for the Australian survey was derived from the membership of the Australian Institute of Management (AIM). A postal survey was used to obtain the data in May 1999. From a mail-out of 493 questionnaires, 93 useable questionnaires were returned, yielding a response rate of 19 per cent. Of the resulting sample 62 per cent of managers classified themselves as senior managers, 37 per cent as middle managers and 1.0 per cent as junior managers. The average age of the managers in the sample was 44.7 years (standard deviation: 5.57 years), and this fits with the senior profile of this group. Females comprised 20 per cent of the sample. The predominance of males in the sample is consistent with the 7 predominance of males in the general management population (Affirmative Action Agency, 1999). The majority of respondents (73 per cent) were from the private sector, and 10 per cent from foreign companies. Membership in the AIM generally mirrors the characteristics of the management population in Australia. According to officials of the AIM, demographics of the sample are sufficiently similar to overall membership. The percentage of women, public servants and average age that make up the sample are reflective of overall membership, and while the AIM database was unable to provide confirmation with respect to the representativeness of sample levels of management and foreign ownership, nevertheless officials believe the sample demographics are representative of AIM membership. Furthermore, the AIM recently conducted a short survey of their members under 35 years of age. Interestingly, in this study a high number of respondents (27 percent) classified themselves as senior managers. With today’s flatter management structures, many may consider themselves to be senior managers, when perhaps a few years ago, the same level of responsibility would have been deemed to be middle management. Samples from South Africa, China and India were obtained using comparable sampling frames, but also ensuring that the cultural and regional diversity of the management populations were represented in South Africa (n = 426), China (n = 216) and India (n = 79). These generally matched the Australian sample in terms of proportion of public sector managers, but foreign companies in China (28.2 per cent) and South Africa (21.4 per cent) represented a higher proportion than in the Australian sample. Although the other countries had lower proportions of managers rating themselves as senior, generally managers reported having more subordinates in China and South Africa, and on average the same in India. On average managers’ organisations were reportedly smaller in Australia than the other countries, 8 which may account for the difference in perceived higher level of management compared with the other countries. RESULTS Operational and Strategic Orientation Constructs which were robust across responses were used to provide perceptions (current, ideal and future organisation) of general operational and strategic orientation. The control orientation construct comprises a scale of four questionnaire items: very hierarchical, very centralized, very authoritarian and many strict rules. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale across national groups ranges from .804 to .761. The people orientation construct comprises five items: consults employees, provides equal opportunities for all, clear policies on employee relations, motivates employees and has the well being of its people as a major objectives. Cronbach’s alpha ranges from .842 to .558. The results orientation construct comprises five items: oriented towards the market, clear objectives, very successful, clear policies on client or customer relations and results oriented. Cronbach’s alpha ranges from .876 to .632. While Carmines and Zellar (1979) note that Cronbach’s alpha should be greater than 0.80 for frequently used scales, all three scales are sufficiently reliable for this exploratory study as the alpha coefficients exceed 0.50 (Soutar, McNeil and Molster, 1995). However, the constructs require verification in future studies to determine if they are stable. Summary results presented in Table 1 suggest that Australian organisations are less control oriented than Chinese and South African organisations, and compared to their Chinese and South African counterparts, Australian managers believe less control is ideal. However, they perceive little change to the current situation in the future. Australian organisations are also more people oriented than Chinese organisations, and compared to Chinese and Indian respondents, managers perceive a stronger people orientation as ideal. Australian organisations appear to be moving toward both a greater people and results orientation in the future, in contrast to Indian organisations. 9 ‘Table 1 here’ There are some differences between private and public sectors. Across the national groups, managers indicate that the public sector is generally more control oriented (t.stat. 4.49, sign. .000), less people oriented (t stat. 3.70, sign. .000) and less results oriented (t stat. 6.15, sign. .000). Operational Characteristics Single item measures are used to provide a profile of operational characteristics (Table 1) and include constraints and influences (being bound by government regulations, influenced by family, strength of trade unions), operational features (degree of change, extent of foreign ownership), management style of operating (risk taking, flexibility, ethicality, using well defined rules of operations), internal dynamics (extent of internal competition for promotion and inter-ethnic harmony, encouragement of different opinions) and management expertise and skills. Constraints and Influences Australian companies are less bound by government regulations than Chinese and South African organisations, and compared to Chinese, South African and Indian respondents, Australian managers believe less regulatory influence is ideal. However, there appears to be no change to the status quo in the future. Australian respondents report weak trade unions, in contrast to South Africa organisations, which recorded the strongest trade union activity. Compared to the other nationalities, 10 Australians believe still less union influence is ideal, although again, there appears to be little change to the current situation in the future. Operating Features Australian managers indicate a higher rate of organisational change than Chinese and Indian managers, but express a desire for significantly less change compared to the other nationalities in the investigation. Australian organisations recorded the least level of foreign ownership, with their managers responding that they perceive this to be significantly more ideal than both South African and Chinese managers do. While Australian respondents expect this to increase in the future, significantly less so than do the South Africans. Style of Organisational Management Australian organisations appear to be more risk taking (and believe this is more ideal) than Chinese organisations, more flexible than the South Africans, and significantly more ethical than Chinese, Indian and South African organisations. Australian managers believe an even higher level of ethicality is ideal compared to their Chinese, Indian and South African colleagues, and believe that their organisations are moving is this direction in the future. Internal Dynamics In terms of competition for promotion, Chinese and South African organisations appear to be more dynamic than Australian organisations, with this situation expected to continue in the future. And while Australian managers perceive more competition is ideal, significantly less so than the other nations surveyed. Australian organisations are characterised by more diverse opinions compared with their Chinese counterparts, as well as more inter-ethnic harmony than the South Africans. 11 Compared to Chinese and Indian managers, Australian managers believe that inter ethnic harmony is more an ideal, and believe that their organisations are moving in this direction in the future. Management Expertise Australian managers believe that their organisations possess significantly higher levels of management expertise than their counterparts in Chinese organisations, and compared to Indian respondents, believe more is ideal. Management Motivation Single item measures were used to compare differences in motivation (Table 2). Australian managers are more motivated by autonomy and uncertainty in their jobs than their Chinese and Indian colleagues, and compared to the Indians, more motivated by personal development opportunities. Interestingly, Australian managers believe that their colleagues are less motivated by these opportunities. They are also more motivated by achievement than are Indian managers. In contrast to the Chinese, the Australians are significantly less motivated by independence and control, and compared with the Chinese and South Africans, less motivated by economic security. Finally, in contrast to South African and Indian managers, they are less motivated by ambition (recording the lowest level for these items of the countries in the survey). ‘Table 2 here’ Management Commitment Table 2 also provides comparative results for the direction of management commitment. Compared to their Chinese, Indian and South African counterparts, Australian managers 12 indicate a significantly higher commitment to ethical principles with lower commitment to business objectives regardless of means, and a lower commitment to organisation, results, work and relatives. Management Principles Australian managers have a higher internal and lower external locus of control than Chinese, Indian and South African managers, and base their decisions more on outcomes than South African managers, and less on pre-set principles compared to Chinese and South African managers. The Australians are the most trusting of employees of the nations surveyed. Australian managers are more achievement oriented than their Chinese and Indian colleagues, and significantly less status oriented than managers from China, India and South Africa. However, they see their management colleagues as more status oriented and less achievement oriented than themselves. Management Practices Australian managers rely less on hierarchy than do their Indian and South African colleagues, and less on rank than do the Chinese, but are on par with the other nationalities. They are less egalitarian than their Indian and Chinese counterparts, but communicate and provide information more openly. They are less confrontational than Chinese and South African managers. DISCUSSION Results documented above suggest cross-cultural differences exist between Australia and the other countries surveyed. Many of the main differences are with China, and while similarities with other Anglo countries exist, there are exceptions; these are also highlighted. Australia and China 13 Significant differences exist between Australian and Chinese management practices including the use of rank, extent of confrontation and assertiveness, information sharing and communication, and also in management principles; in particular status/achievement orientation, philosophical assumptions about employees and extent of internal/external control (Table 2). Further differences were identified between Chinese and Australian motivators: Chinese managers are significantly more motivated by economic security, independence and control in contrast to their Australians counterparts. Significant differences were also identified in the direction of management commitment. Australian managers are significantly more committed to ethical principles and less committed to business objectives regardless of means, organisation, results, and work compared to Chinese managers (Table 2). Further differences were identified in operational and strategic orientations: Chinese organisations are generally more control oriented than Australian organisations, with Chinese managers happy with this situation. In contrast, Australian organisations appear to be more people oriented than Chinese organisations, with Australian managers believing this to be significantly more ideal than Chinese managers (Table 1). Results from the Chinese sub-sample (from management practices such as the use of rank and management principles such as status basis, to control as a management motivator and primary control orientation) may reflect the Chinese culture and predominant ideology, Confucianism. Confucianism is basically authoritarian, and stresses hierarchical principles and status differences, creating a largely autocratic managerial style (Semler, 1999). Vertinski et al. (1990) also note that the ascribed status orientation rather than achieved status is rooted in Confucianism. The low score given to the use of rank by Australian managers is perhaps a reflection of the cultural emphasis on equalitarianism in Australian society. Like ‘mateship’, the cultural 14 emphasis on equalitarianism in Australian society is well established (Encel, 1970). Encel (1970: 56) defines the term equality as …one which places a great stress on the enforcement of a high minimum standard of well-being, on the outward show of equality and the minimisation of privileges due to formal rank… The primary Australian strategic and operational people orientation supports previous management research beginning more than a quarter of a century ago with England (1975, 1978) and associates (Whitely and England, 1980) and continuing today (Jenner, 1982; Westwood and Posner, 1997) which have consistently concluded that Australian managers have a highly humanistic orientation, and place major importance on values that reflect a high concern for others. Australia and India Both India and Australia were (and in the case of Australia, still is) part of the British empire: Australia’s Western traditions began when Britain colonised Australia as a penal colony in the late eighteenth century, and for most its history has retained strong links with Britain. India’s links with Britain ended in 1947 when British rule ceased. Because of this long affiliation with Britain, it may seem more likely that its management styles and organisations would be like that of other Anglo countries. In the current study, both Australian and Indian managers report a moderate degree of control orientation. Similarities also exist in operational organisational characteristics. These include a weaker degree of government regulation and weak trade unions; extent of foreign ownership; organisational flexibility; and higher inter ethnic harmony. However, while Indian managers are more ambitious than their Australian colleagues, they are comparatively less motivated by autonomy, personal development, achievement and managing uncertainty (Table 2). England (1975) also reported cross-cultural differences 15 between Indian and Australian managers. In a study of managerial values conducted more than twenty five years ago, England (1975) concluded that Indian managers value stable organisations with minimal or steady change, and this fits with the low score attached to managing uncertainty. Results suggest Indian managers are significantly more committed to business objectives regardless of means, organisation, results and work than their Australian counterparts. Other studies also report that Indian managers are strongly focussed on organisational compliance, including [non aggressive] pursuit of objectives (England, 1975). More recent research (e.g., Pareek and Rao, 1992; Rohmetra, 1995) suggests that the liberalization of the Indian economy necessitated a move away from a control orientation, to both a results and people oriented approach, which emphasises a humanistic as well as an instrumental approach to managing. However, the operational and strategic orientations identified in the current study also suggest Indian respondents perceive a stronger people orientation as significantly less ideal than do the Australians, and compared to their Australian counterparts, believe that their organisations will be significantly less people and results oriented in the future. The mean score of 3.05 for Australian organisations’ control orientation suggests a moderate control orientation. This result, taken together with the desire expressed by managers for significantly less control, yet the belief that organisations will continue to be control oriented in the future may arguably, add to a growing body of literature suggesting that Australian business continues to be demonstrate a ‘command and control’ focus (Karpin 1995; Kabanoff and Daly in press). Kabanoff and Daly (in press) concluded that results such as these support criticisms of Australian business culture, namely that it is ‘too top-down’ and inflexible in style. 16 Kabanoff, Jimmieson, and Lewis (in press) suggest that ‘command and control’ style organisations endure and thrive in a relatively stable, predictable and undemanding environment. They believe that Australia may have provided a fertile breeding ground for this type of organization, as for much of the twentieth century, Australian organisations have operated in a centrally controlled industrial relations environment, protected from foreign competition by high tariff barriers and benefited from high prices for exported commodities. And as a result, Australian organisations have enjoyed a comfortable, bureaucratically controlled existence. However, as these conditions have ceased and, are unlikely to return in the future, Australian managers’ belief of a continued control orientation raises questions about the efficacy of changes to organizational structures, policies and practices (Dunphy and Stace, 1990), reportedly designed to move organizations away from a ‘command and control’ approach. Indian managers are comparatively less committed to ethical principles (Table 2) and ethical organisational management (Table 1) than their Australian counterparts, in contrast to England’s (1975) study that reported both Indian and Australian managers mangers to have a high moralistic orientation. Australian managers’ commitment to ethics is consistent with a longstanding body of research that recognises that Australian managers demonstrate significant ‘moralistic’ orientation (Jenner, 1982; Dowling and Nagel, 1986; Westwood and Posner, 1997; Milton-Smith, 1997). Indian managers rely more on hierarchy than do the Australians and are more egalitarian, but do not communicate and give information as openly as the Australians (Table 2). Smith and Thomas’s (1972) study suggests that while Indian managers at both middle and senior levels in organisations profess a belief in group-based, participative decision-making, they have 17 little faith in the capacity of workers for taking initiative and responsibility. This may explain why Indian managers do not communicate or provide information openly. Sharing information with subordinates and communicating openly could also be characterised as practices representing employee consultation, aimed at least in part, at facilitating change management (Kramar and Lake 1997). This also fits with the significantly higher level of change occurring in Australian organisations compared to Indian organisations. Indian managers are significantly more status and less achievement oriented than their Australian colleagues (Table 2). Again, this fits with England’s (1975) study which indicates that the values associated with Indian managers include valuing a status orientation. Australia and South Africa Because of South Africa’s relatively long history of foreign investment with companies which are heavily influenced by western management principles, it might seem more likely that South African management and organisational characteristics be more like that of other Anglo countries. Results suggest both Australian and South African organisations exhibit a people and results orientation. However, South African organisations are significantly more control oriented than Australian organisations (Table 1). Other studies have also characterized South African organisations as bureaucratic (Jackson, 1993), hierarchical, centralized and fairly rule-bound (Jackson, 1999). Significant differences also exist between operational organisational characteristics: South African organisations have stronger government regulations and trade unions, and a higher level of foreign ownership and competition for promotion. Australian organisations are, however, more flexible, ethical and exhibit higher levels of inter ethnic harmony (Table 2). 18 A number of the Australian results are consistent with previous research. For instance, responses to items 15 (weak trade unions), and 23 and 8 (flexible and ethical organisational management) support prior studies that have identified declining trade union influence (ACIRRT 1999; Peetz 1999) and flexible and ethical organisational management (England 1975 1978; Jenner 1982; Dowling and Nagel 1986; Westwood and Posner 1997; MiltonSmith 1997). Given South Africa’s relatively long history of foreign investment with companies, it should not be surprising that South African managers perceive a higher level of foreign ownership than do Australian managers. Differences occurred in terms of factors that motivate both Australian and South African managers: South African managers are significantly more motivated by economic security and ambition. Significant differences also exist in management commitment: South African managers have a higher commitment to organisation, results, work and business objectives compared to their Australian counterparts (Table 2). Significant differences were also found between the responses to management principles: Australian managers have a lower external locus of control, and base their decisions more on outcomes (teleological considerations) and less on pre-set principles (deontological considerations) than do the South Africans. Australian managers are significantly more trusting of employees and less status oriented than South African managers. With respect to management practices, Australian managers are significantly less reliant on rank than South African (and Indian) managers. In fact, an Australian manager is likely to demonstrates his or her worth and commitment to the firm’s goals, and also win respect and praise from their workers by ‘rolling up his or her sleeves’ and ‘pitching in’ on the factory floor in an emergency. Conversely, a manager who fails to refer a subordinate to a more knowledgeable authority would be viewed as an egomaniac (Mahoney, Trigg. Griffin and Pustay. 1998). 19 South African managers are, however, more confrontational than Australian managers (Table 2). Table 1 also shows that Australian organisations are characterised by more inter - ethnic harmony than South African organisations. Roodt (1997) suggests that based on a legacy of apartheid, South African organizations may be management-worker adversarial and discriminatory. MANAGEMENT AND RESEARCH IMPLICATIONS Significant cross-cultural differences have been identified and documented in the previous section. Clearly, such differences have the potential to cause difficulties in international business. The success of cooperative undertakings such as international joint ventures, for example, depends upon selecting compatible partners. Lasserre and Schutte (1995) suggest a satisfactory fit along four dimensions (strategic, organisational, resources and cultural) must be achieved. The strategic dimension includes compatibilities between the respective partners’ strategic objectives; however, the current study identified significant differences between Australian, and Chinese and South African organisations’ operational and strategic orientations. Sharing the same business logic is a requirement for cultural fit. Yet in terms of management principles, significant differences existed in all of the items between Australia and China, India and South Africa, and 6 of the 8 management practices. Clearly, such differences have the potential to cause considerable problems managers need to be aware of, and resolve. Findings in this study may also be useful to international human resource managers formulating motivational strategies, particularly in China, where it is widely recognised that the Chinese labour pool is facing a serious shortage of skilled managers. Furthermore, the retention of managers in foreign firms in China is a challenging issue (Lindholm, 1999; 20 Wright et al, 1998). Organisations with the potential to meet the motivation needs of Chinese managers clearly have an advantage over competitors in the ‘people game’ (Wright et al, 1998) - attracting and retaining Chinese managerial staff. Chinese reforms implemented in 1978 have brought unprecedented changes to management (Zhu, 1997) and include a move away from the ‘iron rice bowl’ approach to managing employees, and as a result, a reduction in lifetime employment. Yet, in the present study, Chinese managers are significantly more motivated by economic security than their Australian colleagues. These findings may act as a starting point for future research examining the role and importance of managerial motivational factors in the international context, including China. As the Chinese economy continues to grow and move toward a quasi-market economy, will the achievement motivation drive in the management population increase? Cyr and Frost (1991) suggest that Chinese workers are becoming more goal-achievement oriented rather than egalitarian. In the current study, Chinese managers, like their Australian colleagues, report being motivated by opportunities to grow and develop. Yet high achievers would not ordinarily give high scores to security-related goals (e.g., job security). Yet another study by Elizur, Borg, Hunt and Beck (1991) indicates a low importance of instrumental values such as pay, benefits and working conditions. Furthermore, Zhao (1995: 127) reports that Chinese employees prefer reward differentials to be ‘determined primarily according to individual contributions’. However, Chinese managers in this study responded that reward should be based upon status, not achievement. Limitations 21 It is important to remember that this exploratory study was designed to collect wide-ranging, descriptive, quantitative data using a questionnaire which is relatively straightforward to complete. As such it contains limitations which should be considered when assessing the results. In particular, single item, quantitative measures were used to provide a profile of operational characteristics, and management motivation, commitment, principles and practices, and can only provide indicative results. It is intended that these results are seen as a first step in exploring issues raised in the survey, particularly results identified above that are inconsistent with previous research. Future research may deal with the limitations of this study outlined above, for example by employing qualitative research methods such as interviewing using open-ended questions. Similarly, by surveying employees drawn from the same workplaces as managerial respondents, and linking data from the employee surveys to items in the managerial survey, a means is provided to explore the relationship between managerial perceptions and employee experience (Harley, 1999). CONCLUSION It is widely accepted that the future well being of the Australian economy depends to a large extent upon the global competency of its enterprises, including their ability to efficiently produce and export both elaborately transformed manufactures, and services. The Karpin Report (1995) identified the development of internationally competitive enterprises as the fundamental means of achieving improved living standards for Australians, and the ability to manage issues affecting international business is paramount to Australian managerial and business success. 22 The management profiles developed in this study will be useful to managers, both in Australia and offshore, where many Australian companies increasingly do business, attempting to reconcile differences in management approaches in the international context. They may also aid in the development of management systems, structures and practices that are consistent with the respective cultural values and expectations. Furthermore, by extending our understanding of the impact of national cultures and social systems upon both organisation and management, Adler (1997) and Teagarden et al. (1995) argue that management practices from developed countries can be appropriately adapted and transferred to emerging countries. 23 REFERENCES ACIRRT (1999) Australia at work: Just managing? Sydney: Prentice Hall Adler, N. (1997) International dimensions of organisational behaviour, 3rd edn. Ohio: SouthWestern College Publishing. Affirmative Action Agency (1999) Women in management. [Online].Available:http://www.eeo.gov.au/student/statistics/index.html#management [1999, November 30] Alpander, G.G., and Carter, K.D. (1991) Strategic multinational intra-company differences in employee motivation. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 6(2): 25-32. Austrade (2000) Austrade Online [Online]. Available: http://www.austrade.gov.au/index.asp [January 2000] Burrell, S. (1999) Now, at your service. The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 October: 101, 105. Carmines, E.G. and Zellar, R.A. (1979) Reliability and Validity Assessment. In J.L. Sullivan (ed.) Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in Social Sciences, 07-017 (Sage Pubns., Beverly Hills and London) Cyr, D. and Frost, P. (1991) Human resources management practice in China: a future perspective, Human Resource Management, 30(2): 199-215. De Cieri, H. and Dowling, P.J. (1995) Cross-cultural issues in organisational behaviour. In C.L. Cooper and D.M. Rousseau (eds.) Trends in organisational behaviour, vol.2. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Dowling, P.J. and Nagel, T.W. (1986) Nationality and work attitudes: a study of Australian and American business majors. Journal of Management, 12(1): 121-128. Dunphy, D. and Stace, D. (1990) Under New Management: Australian Organizations in Transition Sydney: McGraw Hill. 24 Edwards, R.W., O’Reilly, H. and Schuwwalow, P. (1997) Global Personnel skills: A Dilemma for the Karpin committee and Others. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 35(3): 80-89. Elizur, D., Borg, I., Hunt R. and Beck, I. M. (1991) The structure of work values: a crosscultural comparison. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 12: 21-38. Encel, S. (1970) Equality and authority. London: Tavistock. England, G.W. (1975) The Manager and His Values. Cambridge (MA): Ballinger Publishing Co. England, G.W. (1978) Managers and their value systems: a five country comparative study. Columbia Journal of World Business, 13(2): 33-44. England, G.W. (1986) National work meanings and patterns-constraints on management action. European Management Journal, 4(3): 176-84. Evans, W.A., Hau, K.C. and Sculli, D. (1989) A cross-cultural comparison of managerial styles. Journal of Management Development, 8(3): 5-13. Feather, N.T. (1986) Value systems across cultures: Australia and China. International Journal of Psychology, 21: 697-715. Harley, B. (1999) The Myth of Empowerment: Work Organisation, Hierarchy and Employee Autonomy in Contemporary Australian Workplaces. Work, Employment & Society, 13(1): 41-66. Harris, M. (1994) Pearl’s lustre lures our industry. Sydney Morning Herald, 12 September: 7. Hofstede, G. (1980) Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values, Newbury Park (CA): Sage Hofstede, G. (1994) The business of international business is culture. International Business Review, 3(1): 1-14. Hui, C.H. (1990) Work attitudes, leadership styles and managerial behaviour in different cultures. In R. W. Brislin (ed.) Applied Cross-cultural Management London: Sage. 25 Jackson, D. (1993) Organizational culture within the South African Context. People Dynamics, 11(6): 31-34. Jackson, T. (1993) Ethics and the art of intuitive management. European Management Journal, 20th Anniversary edition, 57-65. Jackson, T. (1999) Managing change in South Africa: developing people and organisations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 10(2): 306-26. Jenner, S.R. (1982) Analysing cultural stereotypes in multinational business: United States and Australia. Journal of Management Studies, 19: 307-325. Kabanoff, B. Jimmieson, N.L. and Lewis, M.J. (in press) Psychological contracts in Australia: A “Fair Go” or a “Not-So-Happy Transition? In D. Rousseau, and R. Schalk, (eds.) Psychological Contracts in Employment: International Perspectives, Sage. Kabanoff, B. and Daly, J.P. (in press) Values Espoused by Australian and US organisations. Applied Psychology: An International Review. Karpin, D.S. (1995) Enterprising Nation-Renewing Australia’s Managers to Meet the Challenges of the Asia-Pacific century, Report of the Industry Task Force on Leadership and Management Skills, (Karpin Report) Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. Kluckhohn, F. and Strodtbeck, F.L. (1961) Variations in Value Orientations. Connecticut: Greenwood. Kramar, R. and Lake, N. (1999) Price Waterhouse Cranfield project on international strategic human resource management. Sydney: Macquarie University. In Kramar, R ‘Policies for managing people in Australia. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 37(2): 24-32. Lasserre, P. and Schutte, H. (1995) Strategies for Asia Pacific. Melbourne: Macmillan. Laurent, A. (1989) A cultural view of change. In P. Evans, Y. Doz and A. Laurent (eds.) Human Resources Management in International Firms: Change Globalization, Innovation, London: Macmillan. 26 Lindholm, N. (1999) Performance management in MNC subsidiaries in China: A study of host-country managers and professionals. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 37(3): 18-35. Mahoney, D., Trigg, M., Griffin, R. and Pustay, M. (1998) International Business: A Managerial Perspective. South Melbourne: Longman McGregor, D. (1960) The Human Side of Enterprize. New York: McGraw-Hill. Milton-Smith, J. (1997) Business ethics in Australia and New Zealand. Journal of Business Ethics, October, 16 (14): 1485-1497. Pareek, U. and Rao, T. V. (1992) Designing and Managing Human Resources Systems. New Delhi: Oxford and IBH. Peetz, D. (1999) Nearly the Year of Living Dangerously: In The Emerging Worlds of Australian Industrial relations. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 37(2): 3-23. Reynolds, P.D. (1986) Organisational culture as related to industry, position and performance: a preliminary report. Journal of Management Studies, 23(3): 333-45. Rohmetra (1998) Human Resource Development in Commercial Banks in India. London: Ashgate. Roodt, A. (1997) In search of a South African corporate culture. Management Today, 13(2): 14-16. Rotter, J.B. (1966) General expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80 (1) Whole No 609. Soutar, G.N. McNeil, M. and Molster, C. (1995) A Management Perspective on Business Ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 14: 603-611. Semler, J. (1999) Western Business Expatriates’ Coping Strategies in Hong Kong vs the Chinese Mainland. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 37 (2): 92-105. Stening, B.W. and Ngan, E.F. (1997) The Cultural Context of Human Resource Management in East Asia. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 35(2): 3-15. 27 Teagarden, M.B., Von Glinow, M.A., Bowden, D.E., Frayne, C.A., Nason, S., Huo, Y.P., Milliman, J., Arias, M.A., Butler, M.C., Geringer, J.M., Kim, N.K., Scullion, H., Lowe, K.B. and Drost, E.A. (1995) Towards building a theory of comparative management research methodology: An idiographic case study of the best international human resources management project. Academy of Management Journal, 38: 1261-87. Trompenaars, F. (1993) Riding the Waves of Culture. London: Brealey Vertinski, I., Tse, D.K., Wehrung, D.A. and Lee, K.H. (1990) Organisational design and management norms: a comparative study of managers' perceptions in the People's Republic of China, Hong Kong and Canada. Journal of Management, 16 (4): 853-67. Wagner, J.A. (1995) Studies of individualism-collectivism: effects on cooperation in groups. Academy of Management Journal, 38 (1): 152-172. Westwood, R.J. and Posner, B.Z. (1997) Managerial values across cultures: Australia, Hong Kong and the United States. Asia Pacific Journal of Management,14: 31-66. Whitely, W. and England, G.W. (1980) Variability in Common Dimensions of Managerial Values due to Value Orientation and Country Differences. Personnel Psychology, Spring :77-89. Wright, P., Mitsuhashi, H. and Chau, R (1998) HRM in Multinationals Operations in China: Building Human Capital and Organisational Capability. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 36 (2): 3-14. Zhao, Y.W. (1995) Chinese motivation theory and application in China: An overview. In H.S.R. Kao, D. Sinha and S.H. Ng (eds.) Effective organisations and social values (pp.117-31). New Delhi/Thousand Oaks/London: Sage Zhu, C. (1997) Human resource development in China during the transition to a new economic system. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 35(3): 19-44. 28 Curren Tukey* Ideal Tukey* Future Tukey* t Operational and strategic orientation Control orientation People orientation Results orientation 3.05 3.30 3.48 <CS >C ns 2.51 4.50 4.55 <CS >CI ns 3.12 3.52 3.82 <CS >I >I Constraints and influences 24 Bound by government regulations 25 Influenced by family members 15 Strong trade unions 3.37 2.24 1.97 <CS ns <S 2.73 2.07 1.84 <CSI ns <ISC 3.40 2.21 1.94 <C ns <ISC Operationing features 10 Undergoing rapid change 11 Foreign owned 3.77 1.49 >CI <S 3.62 1.47 <SIC <SC 3.80 1.74 ns <S 2.87 3.23 4.17 3.43 >C >S >CIS ns 3.59 4.17 4.78 4.02 >C ns >CIS ns 3.13 3.42 4.26 3.58 ns ns >CIS <C,>I Internal dynamics 27 Much competition for promotion 26 Encourages diversity of opinions 16 Inter-ethnic harmony 2.72 3.15 3.90 <CS >C >S 3.20 4.31 4.47 <CIS ns >CI 2.88 3.23 4.06 <CS ns >S Management expertise 19 High level of management expertise and skills 3.34 >C 4.67 >I 3.60 ns 2 23 8 22 Style of organisational management Risk taking Very flexible Very ethical Has clear and well defined rules of action Note: C(hina), I(ndia), S(outh Africa). Mean scores are indicated for Current (my organisation at the moment), Ideal (the way I would like it to be) and Future (the way it is going). Scores are from 1(not like this at all) to 5 (exactly like this). * Tukey multiple comparison test p<.001. Table 1. Australian organisational characteristics: an international comparison 29 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Management motivation Preferring the security of a steady job (Economic Security) Preferring work to be unpredictable (Managing Uncertainty) Very ambitious to reach the top (Self Enhancement) Freedom in job to adopt own approach (Autonomy) Eager for opportunities to learn and develop (Personal Development) Setting self difficult goals (Achievement) Enjoying, above all else, to work as part of a team (Belonging) Preferring, above all else, to work alone (Independence) Preferring, above all else, to direct other people (Control) Management commitment 12 Depending only on self (to Self) 11 Making sacrifices for the good of the group (to Group) 19 Being completely loyal to the organisation, above all other things (to Organisation) 14 Regarding the well-being of its people as the objective of an organisation (to People) 15 Considering the results of the organisation as being paramount (to Results) 16 Condoning all business practices if objectives are met (to Business Objectives) 17 Believing managers must act completely ethically (to Ethical Principles) 10 Believing that work is the most important thing in life (to Work) 18 Honouring responsibilities toward relatives (to Relatives) Management principles 20 Believing that if one is motivated enough anything can be achieved (Internal Locus of Control) 21 Believing that own achievement is based very much on outside forces (External Locus of Control) 22 Basing decisions on pre-set principles, rather than outcomes (deontology) 23 Basing decisions on likely outcomes, not on pre-set principles (Teleology) 24 Believing that generally employees are not to be trusted (Mistrust of Human Nature) 26 Believing that reward should be based on status (Status Orientation) 27 Believing that reward should be based on achievement (Achievement Orientation) Management practices 28 Working through the hierarchy at all times (Reliance on Hierarchy) 29 Keeping personal distance from subordinates (Use of Rank) 25 Having a completely democratic management style (Participation) 30 Socializing with employees outside work (Egalitarianism) 31 Communicating openly (Communicating Openly) 32 Giving subordinates open access to information (Providing Open Information) 13 Being confrontational and assertive (Confrontation) 33 A high level of management knowledge and skills (Management Capability) Self Tukey Others Tukey Required Tukey 3.22 3.52 3.37 4.49 4.61 <CS >CI <SI >CI >I 3.79 2.90 3.30 3.78 3.57 <CS >C <SI >S <C 2.91 3.58 3.65 4.27 4.61 <CIS >C <CIS ns ns 4.08 3.94 2.46 3.07 >I ns <C <C 3.23 3.37 2.69 3.39 ns ns <C ns 4.20 4.12 2.37 3.16 ns <S <C <C 2.71 3.65 3.26 ns ns <CIS 2.67 2.92 2.96 ns ns <S 2.44 3.72 3.36 <I <CIS <CIS 4.02 ns 3.23 ns 3.94 ns 2.74 <CIS 3.01 <CS 3.14 <CI 1.82 <CIS 2.27 <CIS 2.08 <CIS 4.67 >CIS 3.89 >CIS 4.57 >CI 2.25 3.39 <CIS <C 2.58 3.25 <CIS <C 2.69 3.18 <CIS <C 4.23 >C 3.45 ns 4.23 <S 2.29 <CS 2.64 <CIS 2.28 <CIS 2.59 <CS 2.89 <C 2.71 <C 3.58 >S 3.22 ns 3.67 ns 1.56 <CS 2.26 <CS 1.65 <CS 1.62 <CIS 2.42 <CIS 1.76 <CI 4.56 >CI 3.61 ns 4.46 ns 2.59 <IS 3.22 ns 2.70 ns 2.29 3.54 <C ns 2.91 2.75 <C <C 2.53 3.50 <C ns 2.27 4.43 4.09 <CI >CI >CI 2.86 3.44 3.27 <C >IS ns 3.04 4.52 4.10 <CI >CI ns 2.40 4.15 <CS ns 2.68 3.24 <CS ns 2.75 4.66 <S ns Note: C(hina), I(ndia), S(outh Africa). Mean scores are for Self (Me, as a manager), Others (Managers generally in my organisation), and Required (The type of manager required for the future of the organisation). Score are from 1 (not like this at all) to 5 (just like this). * Tukey multiple comparison test p<.001. Table 2. Australian management characteristics: an international comparison 30 Authors Janice Jones (MCom, University of New South Wales) is a Lecturer in Management within the School of Commerce at Flinders University where she teaches Human Resource Management amongst other management subjects. Her research interests include human resource management, cross-cultural management and ethics. She has worked in the public sector for a number of years. Terence Jackson is director of the Centre for Cross Cultural Management Research (Oxford). He is the Chair of International Human Resource Management at EAP. Professor Jackson’s particular areas of interest and expertise are: human resource management and cross-cultural aspects of managing people internationally. His current research focuses on management ethics in international business situations, international negotiation and management of international teams in joint ventures and strategic alliances. 31