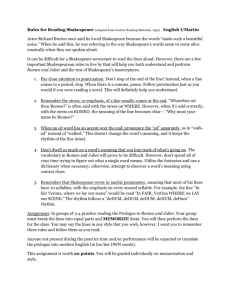

Syllabus - Dr. DR Ransdell, University of Arizona

advertisement

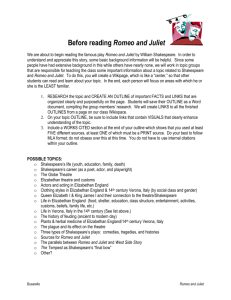

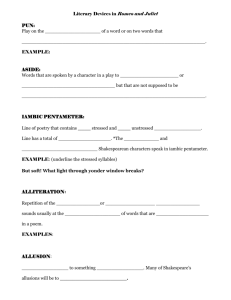

English 499H: Shakespeare in Italy Dr. D.R. Ransdell MT 2:30 p.m.-4 p.m., also R 5/28, 6/25 10:30 a.m.-12 p.m. Orvieto Study Abroad Program Summer May-June 2015 http://ransdell.faculty.arizona.edu Ransdell@email.arizona.edu Course Description: Although William Shakespeare probably never traveled to Italy, he set a third of his plays there. As such, they make for a rich study for students in the Orvieto program. Filmmakers too have capitalized on these Italian connections, making special use of setting in their productions. In this course you will study a variety of these plays in written or cinematic form, read criticism about setting and Shakespeare’s use of Italian elements, and synthesize what you learn about this Italian connection in a final paper that discusses several “Italian” plays. Materials: Note that while hard copies are useful in many ways, all these materials are available electronically via Gutenberg.org and via Amazon Kindle with the exception of the text by Richard Paul Roe, which is available via Kindle. (Gutenberg is free; Kindle copies for Shakespeare plays vary from free to a few dollars.) Othello or Romeo and Juliet The Taming of the Shrew The Merchant of Venice Much Ado about Nothing One play of your choice: Tragedies: Coriolanus, Titus Andronicus, Julius Caesar, Anthony and Cleopatra Comedies: The Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Comedy of Errors (Italian sources), All’s Well that Ends Well, The Winter’s Tale, The Tempest (Italian characters on an unnamed island), Twelfth Night (Illyrian coast) [You could also consider Measure for Measure; it takes places in Vienna but has Italian characters.] Or a similar play, also with an Italian setting, from the Jacobean Era, such as: Johnson, Ben. Volpone Middleton, Thomas. Women Beware Women Webster, John. The Duchess of Malfi Webster, John. The White Devil Roe, Richard Paul. The Shakespeare Guide to Italy: Retracing the Bard's Unknown Travels. NY: Harper Perennial, 2011. Critical sources (Internet/provided on my website) Course Breakdown: Class Presentation 10% Mini-Analyses (4): 40% Final Paper: 50% Note that since this is a college writing course, you are naturally expected to submit writing that is free of grammatical and mechanical errors; otherwise you will lose credit. (See Grammar Highlights below.) For the class presentation the last week of class, you’ll lead a brief discussion of a play of your choice (NOT the ones we have discussed in class). On a 2-3 page “handout,” 1) provide a brief (1-par) summary, 2) a list of key themes from the play, 3) several choice quotes from the play with an explanation as to why they are important, and 4) several quotes from a critical source you’ve found with an explanation as to why they are important. 5) Also provide your critical source. (Material may be provided electronically). [Don’t discuss the final act of your play. Instead entice people to read it.] To begin preparing for your final paper, each week you will write a Mini-Analysis discussing one aspect of the play (in text or film version) in relation to at least one piece criticism. (This means a chapter from Roe, an article, an introduction, or a forward, NOT an anonymous e-source.) For your Mini-Analyses, consider questions such as: How does Shakespeare make use of Italy? How does setting inform or shape each play? What difference does Italy make? How does Italy contribute to Shakespeare’s creations? Why did Shakespeare choose to make his characters Italian? Your Mini-Analyses should be around 1500-2000 words each (3-5 pages). Present a controlling idea in your introductory paragraph and use topic sentences to help readers move among your points. Include quotes from the play and references to at least one critical source. Edit your work according to SWE—Standard Written English. Your Final Paper should discuss at least three “Italian” plays and include research from at least four sources (each Roe chapter counts as a source). Usually you will want to draw quotes from each text you use. Show a sophisticated understanding of course materials and create an in-depth analysis in the form of an organized, edited academic paper. Cite sources inside your paper according to MLA and write a Works Cited page that lists the texts you used. (9-13 pages, approx. 3000-4000 words, more thorough papers generally earn more credit). Sample directions your final papers might take: Playgoer as Traveler: How does being in Italy affect your understanding of Italianate plays? Italy as character: How does the use of Italy enhance/affect Shakespeare’s works? Italy as historical backdrop: How does Shakespeare use key facts to create optimal dramatic tension? Italy vs. England: How does Shakespeare’s use of setting compare from one country to another? Filming Italy: How do directors use vivid Italian settings to punctuate Shakespeare’s plays? Technicalities: Double-space your papers using Times New Roman 12. Late work will be marked down 1/3 grade per class period late. Remember to back up all your work in a couple of places. Barring technical difficulties, I’ll ask you to submit all your work via Dropbox (possibly d2l) in Word or rtf. Classroom Etiquette: Come to class on time and don’t leave until class is over. To avoid distracting classmates, use electronic devices only for course materials. (Use a laptop or a tablet, not a cell phone.) Attendance: You are allowed to miss one class; thereafter, each absence lowers your overall grade by 1%. Final Note: Plays were meant to be seen, not read, of course. If you possibly can, watch film versions of our materials. For example: Zeffirelli’s Taming of the Shrew, Romeo and Juliet Baz Luhrman’s Romeo and Juliet Parker’s Othello Hoffman’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (filmed in Tuscany/Lazio) Radford’s The Merchant of Venice Branaugh’s Much Ado about Nothing (Note: Netflix doesn’t work abroad, but Amazon might have an international version.) Also Note: I’m not sure if our two-day trip will be north to Venice or south to Pompeii. Both are wonderful places! But since two of our plays take place in Venice, you might try to visit that city one way or the other. You might also want to check out Padova (Padua) or Verona. Both are easily accessible by train. Note that it’s important to write the right words, not just any words. However, special effort usually leads to higher grades. Important Note: Summer school goes fast, especially when you’re abroad. Skim if you have to, but keep up. Look ahead and study the syllabus so that you can complete your work on time without it interfering with travel plans and our excursions. You might or might not have an Internet connection where you’re living; plan accordingly. Daily Syllabus Week 1: T 5/26 Introduction. We’ll start discussing Othello and/or Romeo and Juliet. R 5/28 Due to Monday’s orientation, we’ll meet today from 10:30 a.m.-12 p.m. (If you have a conflict with another class, go to it instead; this date was not on the original calendar.) For class: Read/watch Othello/Romeo & Juliet if you’re not familiar with it; read the corresponding chapter in Roe. We’ll assign Acts for next week. F 5/29 Post your mini-analysis on Othello or Romeo & Juliet. (Given our short week, you can post by 5/31 at no penalty, but leave yourself enough time to read the next play.) ================== Week 2: M 6/1 For class: Read/watch The Taming of the Shrew; be prepared to discuss your Act. (Be prepared to summarize it in one sentence, give us any favorite lines, and discuss it within the context of the play as a whole.) T 6/2 For class: Read Roe’s Ch 4; also read a selection from my website. (You can choose other sources; provide them electronically or via a link.) F 6/5 Post your mini-analysis on The Taming of the Shrew (by midnight). Feel free to post earlier. ================== Week 3: M 6/8 For class: Read/watch The Merchant of Venice. Be prepared to discuss your Act. T 6/9 For class: Read Roe’s Chs. 5 & 6. F 6/12 Post your mini-analysis on The Merchant of Venice. ================== Week 4: M 6/15 For class: read Much Ado about Nothing. Be prepared to discuss your Act. T 6/16 For class: Read Roe’s Ch 10; also read a selection from my website. (You can choose other sources; provide them electronically or via a link.) F 6/19 Post your mini-analysis of Much Ado about Nothing. ================== Week 5: M 6/22 For class: Prepare your presentation. Send the “handout” and critical source to us via email before class. We’ll do presentations in class. T 6/23 In class: We’ll finish presentations (if necessary) and brainstorm paper ideas. R 6/25 Extra class: 10:30 a.m.-12 p.m. Draft your final paper for workshopping. (If you have a conflict with another class, go to it instead.) F 6/26 Final Paper “due,” but accepted through July 3rd without penalty. Late papers lose 1/3 grade per day but will be accepted through July 10. Did Shakespeare Visit Italy? . Shakespeare's writings suggest that he visited Italy, although no other evidence is available to indicate that he ever set foot outside of Britain. As for the evidence in his writing, consider that more than a dozen of his plays–including The Merchant of Venice, Romeo and Juliet, All's Well That Ends Well, Othello, Coriolanus, Julius Caesar, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Taming of the Shrew, Much Ado About Nothing, and The Winter's Tale all have some or all of their scenes set in Italy. Consider, too, that plays not set in Italy are often well populated with people having Italian names. For example, although The Comedy of Errors takes place in Ephesus, Turkey, the names of many of the characters end with the Italian ''o'' or ''a'':–Angelo, Dromio, Adriana, Luciana. In Hamlet's Denmark, we find characters named Marcellus, Bernardo and Francisco. Practically all of the characters in Timon of Athens bear the names of ancient Romans– Lucullus, Flavius, Flaminius, Lucius, Sempronius, Servillius, Titus, Hortensius. Of course, it is quite possible that Shakespeare visited Italy only in his imagination From http://www.cummingsstudyguides.net/xTaming.html by Michael Cummings Possible Web Sources: Berry, Ralph. “Shakespeare’s Venice.” Contemporary Review 272.1588 (1998): 252+. Literature Resource Center. Web. Bevington, David. “The Comedy of Errors as Early Experimental Shakespeare.” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 2003. 13-25. Freed, Eugene. “”News on the Rialto”: Shakespeare’s Venice.” Shakespeare in Southern Africa 21 (2009): Web. Jones, Robert C. “Italian Settings.” Studies in English Literature 1500-1900. 10.2 (1970): 251-68. Parks, George B. “The Development of The Two Gentlemen of Verona. The Huntington Library Bulletin (1937): 1-11. Web. Praz, Mario. “Shakespeare and Italy.” Sydney Studies in English. Sydney, 1977. 3-18. Web. <http:/scholarship.library.usyd.edu.au> Parks, George B. “The Development of The Two Gentlemen of Verona. The Huntington Library Bulletin (1937): 1-11. Web. Praz, Mario. “Shakespeare and Italy.” Sydney Studies in English. Sydney, 1977. 3-18. Web. <http:/scholarship.library.usyd.edu.au> Richmond, Hugh Macraie. “The Two Sicilies: Ethnic Conflict in Much Ado about Nothing.” Shakespeare Newsletter Spring-Summer 2007: 17+. Literature Resource Center. Web. Zeeveld, W.G. “Coriolanus’ and Jacobean Politics.” Modern Language Review 57.3 (1962): 321-34. JSTOR. Web. D.R.’s Grammar Highlights Note: following these simple guidelines might help you prevent common mistakes that could lower your grade. When you make grammar mistakes, your readers may have to reread your sentence in order to understand it. That confuses them and makes them lose time. If you make enough mistakes, they’ll start to disagree with your opinions automatically! Instead, observe some simple rules to make your writing more effective. 1) Add a comma after a long introductory phrase: Even though it was long after midnight, I wrote three more drafts of my English essay. This comma helps your readers find the subject of your sentence. 2) Add a comma after a conjunction ONLY when the phrase that follows is an independent clause (a complete sentence). I thought I had enough time to write my essay, but I had to work until dawn to finish my work. (Note the difference: I thought I had enough time to write my essay but had to work until dawn to finish my work. No subject= no comma.) 3) Use commas around non-restrictive (unnecessary) clauses: My roommate, who never turns off her alarm clock, drives me crazy. The sentence could simply read “My roommate drives me crazy.” (If you have two roommates, the information becomes necessary so that you can explain which roommate is the sleepyhead: My roommate who never turns off her alarm clock drives me crazy. My other roommate never bothers to set one.) 4) Divide sentences with a semi-colon; use a comma after words such as “however.” We went to a terrific party last night; however, the food tasted awful. 5) Avoid run-ons. In other words, don’t run two sentences together your readers will be irritated. See what I mean? Run-ons are frustrating for readers because they assume they have misread and have to go back and reread your sentence only to find out that YOU are the one who made the mistake. Instead write: Don’t run two sentences together. Your readers will be irritated. If you want the sentences to work closely together, you might use a semi-colon instead: Don’t run two sentences together; your readers will be irritated. 6) Avoid fragments unless they are clearly used on purpose. A fragment is a word or phrase masquerading as a sentence but that is incomplete in some way. Bad idea? Once in a while it makes sense to use a fragment stylistically, but you have to be careful that it doesn’t seem like a mistake. For example, “Bad idea” isn’t a full sentence, but it demonstrates my example. 7) Avoid “number” mistakes. Grammatically, “everyone” is singular, but “their” is plural. Therefore it’s awkward to write: Everyone should bring their syllabus. Instead make the phrase plural: Students should bring their syllabi. (You can also use the singular form, but it’s awkward too: Everyone should bring his or her syllabus.) 8) Use colons precisely. A colon means one of two things: a list is coming or an example is coming. If you have an example or a direct quote coming, that example/quote might be a full sentence. Johnny told me a lot of things that night: “I’m not sure why I decided to kill Yiolanda, but once I did, the rest came easily.”