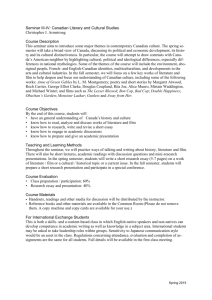

Course Texts - University College Dublin

advertisement